History of the Georgia Institute of Technology facts for kids

The history of the Georgia Institute of Technology (often called Georgia Tech) began with plans to build up industries in the Southern United States after the American Civil War. Founded on October 13, 1885, in Atlanta, it was first known as the Georgia School of Technology. The university opened in 1888 after buildings like Tech Tower were finished. At first, it only offered a degree in mechanical engineering. By 1901, students could also study electrical, civil, textile, and chemical engineering. In 1948, its name changed to the Georgia Institute of Technology. This new name showed that it had grown from just an engineering school into a full technical institute and research university.

Georgia Tech is also linked to two other Georgia universities: Georgia State University and the former Southern Polytechnic State University. Georgia Tech's Evening School of Commerce started in 1912. It later became Georgia State University in 1955. Even though Georgia Tech didn't officially let women enroll until 1952, the night school had female students as early as 1917. The Southern Technical Institute (now part of Kennesaw State University) was also started by Georgia Tech's president, Blake R. Van Leer, in 1948. It was a technical trade school for World War II veterans. It became an independent university in 1981.

The Great Depression made money tight for Georgia Tech. But research during World War II and a big increase in students after the war helped the school a lot. Georgia Tech became integrated peacefully in 1961, allowing students of all races. This was different from other southern universities at the time. The school also did not have protests about the Vietnam War. In the 1990s, Georgia Tech grew its programs and opened campuses in Savannah, Georgia, and Metz, France. In 1996, Georgia Tech was the site of the athletes' village and hosted many events for the 1996 Summer Olympics. Recently, the school has improved its academic rankings. It has also worked to modernize the campus and offer more research and international study options.

Contents

- How Georgia Tech Started (Before 1888)

- Early Years (1888–1896)

- Growing as an Engineering School (1896–1905)

- World War I and Beyond (1905–1922)

- Becoming a Technological University (1922–1944)

- Postwar Changes and Growth (1944–1956)

- Integration and Expansion (1956–1972)

- Research Growth (1972–1987)

- Changes and Growth (1987–1994)

- Modern History (1994–Present)

- Images for kids

- See also

How Georgia Tech Started (Before 1888)

A historical marker on campus shows that Georgia Tech's first buildings were on land once used for forts. These forts protected Atlanta during the American Civil War. The city of Atlanta surrendered in 1864 on what is now the edge of the Georgia Tech campus. The next 20 years saw fast growth in industry. Georgia's factories, railroads, and property values all grew a lot during this time.

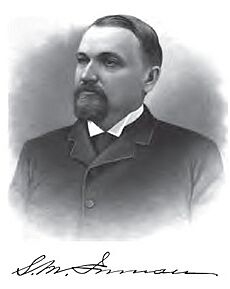

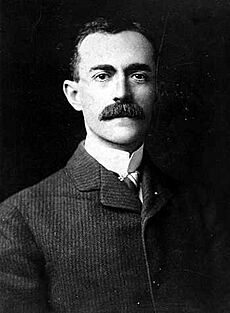

The idea for a technology school came up in 1882. Major John Fletcher Hanson and Nathaniel Edwin Harris, who were former soldiers, believed the South needed better technology. They wanted to compete with the industrial revolution happening in the North. Many Southerners agreed with this idea, called the "New South Creed". They felt a technology school was needed because the South was mostly farming-based. Georgians needed technical training to help the state's industry grow.

With permission from the state government, Harris and a group visited famous technology schools in the Northeast in 1883. These included the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The group liked the "Worcester model," which taught both "theory and practice." This meant students would learn by doing, even making products to sell for the school.

Harris wrote a bill to create the school in 1883, but it faced a lot of opposition. People worried about the cost and didn't always support technical education. In 1885, a new version of the bill was passed. On October 13, 1885, Georgia Governor Henry D. McDaniel signed the bill. This officially created and funded the new school. A committee was then set up to choose where the school would be located.

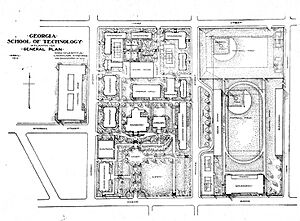

In January 1886, a group was chosen to organize the school. Harris was elected chairman. They asked cities across the state to bid for the school. Five cities offered proposals, including Atlanta. After many votes, Atlanta was chosen. Atlanta's offer included $50,000 from the city and $20,000 from private citizens. It also included a gift of 4 acres of land from Richard Peters.

The school's new location was bordered by North Avenue and Cherry Street. Peters sold 5 more acres to the state for $10,000. This land was on the northern edge of Atlanta at the time. The law that created the school also set aside $65,000 for new buildings.

Early Years (1888–1896)

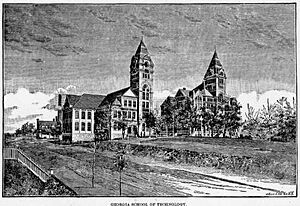

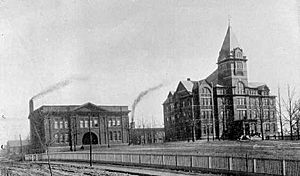

The Georgia School of Technology opened in the fall of 1888 with only two buildings. Isaac S. Hopkins was its first leader. One building, now Tech Tower, had classrooms. The other was a workshop with a foundry and engine room. It was meant to be a "contract shop" where students made goods to sell. This helped the school earn money and taught students practical skills. This "hands-on" method was important for the South's industrial growth. The two buildings were equally important, showing that learning with your mind and hands was key. The contract shop system ended in 1896 because it wasn't making enough money. After that, items made were used for campus offices and dorms.

The first class at Georgia Tech was small. Eighty-five students signed up on October 7, 1888. By January 1889, there were 129 students. Most students were from Georgia. Tuition was free for Georgia residents and $150 for out-of-state students. The only degree was in mechanical engineering, and there were no elective courses. The program was so tough that almost two-thirds of the first class did not finish. The first two students graduated in 1890.

John Saylor Coon became the first Mechanical Engineering and Drawing Professor in 1889. He later became the superintendent of the shops in 1896. Coon helped shift the school away from just vocational training. He focused on balancing shop work with classroom learning. Coon taught students modern ways to solve engineering problems. He also helped make mechanical engineering a professional degree, focusing on ethics and design.

Georgia Tech started its football program with students forming a team called the Blacksmiths. They lost their first three games. So, they found a coach, Leonard Wood, an army officer who had played at Harvard. In 1893, Tech played its first game against the University of Georgia. Tech won 28–6, which was the school's first victory. Angry Georgia fans threw things at the Tech players. This bad treatment started the rivalry known as Clean, Old-Fashioned Hate.

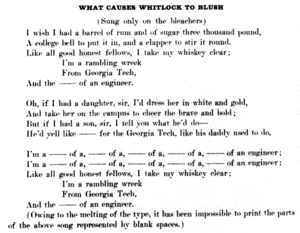

The words to Georgia Tech's famous fight song, "Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia Tech", are said to have come from an early baseball game against Georgia. Some say Billy Walthall, a student, wrote the lyrics around 1893. In 1905, Georgia Tech made it its official fight song. It was first published in the 1908 Blue Print yearbook. Some words were censored as "too hot to print." Later, the first bandmaster, Michael A. Greenblatt, wrote a modern musical version. In 1911, Frank Roman added trumpet parts and made it more famous.

Tech's first student newspaper was the Technologian in 1891. Then came The Georgia Tech in 1894. The Technique was founded in 1911. It has been published weekly ever since, except for a short time when it was twice a week.

Growing as an Engineering School (1896–1905)

In 1888, Captain Lyman Hall became Georgia Tech's first math professor. He became the school's second president in 1896. Hall had an engineering background from West Point. As president, Hall was known for raising money and improving the school. His special project was the A. French Textile School. In February 1899, Georgia Tech opened the first textile engineering school in the Southern United States. It was named after its main donor, Aaron S. French.

Hall wanted to make Tech bigger and attract more students. He added new degrees beyond mechanical engineering. These included electrical engineering and civil engineering in 1896, textile engineering in 1899, and engineering chemistry in 1901. Hall was also very strict. He even suspended the entire senior class of 1901 for returning from Christmas break a day late.

Hall died on August 16, 1905. His death was blamed on the stress of raising money for a new chemistry building. Later that year, the school named the new chemistry building the "Lyman Hall Laboratory of Chemistry" in his honor.

On October 20, 1905, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Georgia Tech campus. He gave a speech on the steps of Tech Tower about how important technical education was. Roosevelt then shook hands with every student. Other presidents, like William H. Taft and Franklin D. Roosevelt, also visited Tech later.

World War I and Beyond (1905–1922)

When John Heisman (for whom the Heisman Trophy is named) became coach in 1904, he wanted the school to have its own football field. In 1905, Heisman had workers clear rocks and level the land. Tech students then built a grandstand. The land was bought by 1913, and John W. Grant donated $15,000 for the first permanent stands. The field was named Grant Field after his son.

An alumni association was formed in 1908. It published its first report that year. This group helped raise money for a big expansion of Georgia Tech's campus in the 1920s.

Georgia Tech's Evening School of Commerce started classes in 1912. It admitted its first female student in 1917. Anna Teitelbaum Wise became the first female graduate in 1919. She then became Tech's first female faculty member.

World War I brought many changes. Georgia Tech hosted a school for army officers and technicians. Tech also started a Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) unit, the first in the Southern United States. The war also led to new programs like an automotive school for the army and a geology department. Federal aid helped create Tech's industrial education department.

The rivalry between Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia grew stronger in 1919. UGA made fun of Tech for continuing football during World War I. Many schools, like UGA, lost male students to the war and stopped playing football. Tech, being a military training ground, still had students. UGA students held a parade making fun of Tech. This led to Tech cutting athletic ties with UGA for a while. They didn't compete again until 1921.

In 1916, Georgia Tech's football team, still coached by John Heisman, defeated Cumberland 222–0. This is the largest victory margin in college football history. Heisman led Tech to its first national title in 1917. After Heisman left, William Alexander took over.

In its early decades, Georgia Tech slowly grew from a trade school to a university. In 1919, the state passed a law to create a State Engineering Experiment Station at Georgia Tech. This station was meant to help the state's industries. However, it didn't get state funding at first.

The later years of President Kenneth G. Matheson's time were hard due to a lack of money. In 1919–1920, facilities for 700 students had to serve 1,365. The school received the same $100,000 funding it had since 1915, but inflation made that money worth less. Matheson managed to get a small increase. In 1922–1923, funding was still low. Matheson had to start charging tuition for in-state students. He said it was a "humiliating burden" to get enough money from the state.

Becoming a Technological University (1922–1944)

On August 1, 1922, Marion L. Brittain became the school's president. He pointed out that Georgia Tech had more students than any other two colleges in Georgia combined, but received the least funding. He worked to convince the state to increase the school's money. A $300,000 grant helped Brittain start the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aeronautics. Today, this school is one of the largest in the U.S. Other achievements during Brittain's time included doubling enrollment and starting a new ceramic engineering department.

In 1929, some Georgia Tech professors started a research club. They wanted to create a state engineering station to help local businesses. This group studied other engineering experiment stations around the country.

The Great Depression threatened Georgia Tech's funding. In 1930, Brittain suggested that all state universities be managed by one central body. This led to the creation of the University System of Georgia (USG) and the Georgia Board of Regents in 1931. Unfortunately for Tech, the board was mostly made up of University of Georgia graduates. Enrollment at Tech dropped during the Depression. Funding from the state also decreased, leading to lower faculty salaries and postponed building repairs.

To save money, the Board of Regents moved the large Evening School of Commerce to the University of Georgia in 1934. They also moved UGA's small civil engineering program to Tech. This was controversial, and students and faculty protested. They worried that Tech would be reduced to just an engineering department of UGA. Brittain felt the lack of Georgia Tech alumni on the board led to this decision. Despite protests, the board stood firm. The Depression also affected sports, as most athletes were in the commerce school. Athletic scholarships were replaced by a loan program. A new industrial management department was created in 1935, which later became Tech's College of Management.

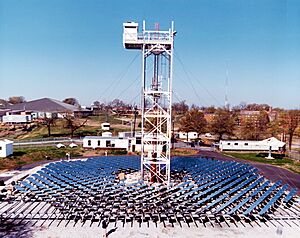

In 1933, the University of Georgia president suggested a "technical research activity" at Tech. This led to the creation of the Engineering Experiment Station (EES) in 1934, with $5,000 in funds. Its first focus areas were textiles, ceramics, and helicopter engineering. Georgia Tech's EES later became the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI).

The EES's early work was done in the basement of the Shop Building. By 1938, the EES was creating useful technology. It needed a way to do contract work outside of the state budget. So, the Industrial Development Council (IDC) was formed. This group later became the Georgia Tech Research Corporation, which handles all contracts for Georgia Tech faculty.

In 1939, EES director W. Harry Vaughan became director of the School of Ceramic Engineering. He left in 1940 and was replaced by Harold Bunger. The ceramics department was temporarily stopped during World War II.

The Cocking affair occurred in 1941–1942. Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge tried to control the state's education system. He fired a University of Georgia professor, Walter Cocking, who was trying to improve academic standards. Talmadge claimed Cocking wanted to integrate the university. This caused a big controversy. Talmadge also tried to put Tech football star Red Barron in a new position at Georgia Tech. Tech alumni protested, and Barron refused the job. Because of Talmadge's actions, all Georgia state colleges for white students, including Georgia Tech, lost their accreditation. This controversy helped Talmadge lose the 1943 election.

World War II led to a huge increase in research projects. The 1943–1944 budget was the first time that industry and government contracts brought in more money than the EES's state funding. Electronics and communications research became very important. Two big projects were studies on radio waves and United States Navy–sponsored radar research.

Until the mid-1940s, students at Tech had to be able to build a simple electric motor. During World War II, Georgia Tech, as an engineering school with strong military ties, quickly joined the war effort. In 1942, the traditional nine-month school year was changed to a year-round system. This allowed students to finish their degrees a year earlier. Students could also complete their engineering degrees while serving in the military. Georgia Tech was one of 131 colleges that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program.

Postwar Changes and Growth (1944–1956)

The school changed its name from the Georgia School of Technology to the Georgia Institute of Technology on July 1, 1948. This new name showed its growing focus on advanced technology and science. Unlike MIT or Caltech, Georgia Tech is a public university. At the same time, former President Marion L. Brittain published The Story of Georgia Tech, the first full history of the school.

The Southern Technical Institute (STI) was started by Tech's president, Blake R. Van Leer, in 1948. It was located in barracks at a naval air station. STI was an engineering technology school to help military members returning from World War II get hands-on experience. Around 1958, the school moved to Marietta. STI became separate from Georgia Tech in 1981.

Before 1952, the only women who attended Georgia Tech did so through the School of Commerce. After it was removed in 1931, women couldn't enroll until President Blake R. Van Leer successfully pushed for it in 1952. His wife, Ella Lillian Wall Van Leer, helped create a support network for women at Tech. She helped set up the first scholarship for female students. In 1954, the Alpha Xi Delta sorority started a chapter at Tech, the first sorority at an engineering school. In 1952, women could only enroll in programs not offered at other Georgia universities. In 1968, the Board of Regents allowed women to enroll in all programs at Tech. Also in 1968, Helen E. Grenga became Tech's first full-tenured female engineering professor. The first women's dorm, Fulmer Hall, opened in 1969. By 2010, women made up about 31% of undergraduate students.

Glen P. Robinson and six other Georgia Tech researchers, including Jim Boyd, started Scientific Associates (later Scientific Atlanta) in 1951. Their goal was to sell antenna structures developed by the EES. Robinson worked without pay for the first year. Despite a tough start, the company succeeded. There was a disagreement about conflicts of interest because the EES director, Gerald Rosselot, was involved in starting Scientific Atlanta. Rosselot eventually resigned from Georgia Tech. His involvement helped the company succeed and paved the way for more technology transfer efforts by Georgia Tech.

This time also saw a big growth in Georgia Tech's postgraduate education programs. This was largely due to the Cold War and the launch of Sputnik. The EES strongly supported this growth. The first Master of Science programs started in the 1920s, and the first doctorate was awarded in 1946. By 1952, about 80 students earned graduate degrees while working at EES. Herschel H. Cudd, EES director from 1952 to 1954, created a new system for promoting researchers. This system is still used today.

Integration and Expansion (1956–1972)

After President Van Leer's death, Paul Weber served as acting president from 1956 to 1957. It was hard to find a permanent replacement because of state laws about segregation and a salary gap. Weber's short time as acting president saw higher enrollment standards and more campus expansion, including the Alexander Memorial Coliseum. Edwin D. Harrison became the new president.

Around 1960, state law said that any white institution that admitted a black student would lose state money. At a meeting on January 17, 1961, most of the 2,741 students voted to support integration. Three years after this meeting, Georgia Tech became the first university in the Deep South to desegregate without a court order. Ford Greene, Ralph A. Long Jr., and Lawrence Michael Williams became Georgia Tech's first three African-American students. They registered for classes on September 18, 1961. The press was kept away to prevent problems, and plainclothes police were on campus. The ANAK Society, a secret student group, claims to have watched over the students to ensure peaceful integration.

There was little reaction from Tech students. As former Atlanta mayor William Hartsfield said, they were "too busy to hate." On the first day, the Ku Klux Klan marched near Georgia Tech and picketed President Harrison's house. Lester Maddox chose to close his restaurant rather than desegregate after losing a legal battle. In 1965, John Gill became The Technique's first black editor. Tech's first black professor, William Peace, joined the faculty in 1968.

The Ramblin' Wreck, the famous 1930 Ford Model A car, became the official mascot during this time. The Wreck is at all major sports events and leads the football team into Bobby Dodd Stadium. Dean of Student Affairs Jim Dull saw that students loved classic cars and wanted an official one. In 1960, Dull started looking for a pre-war Ford. He found a polished 1930 Ford Model A owned by Captain Ted J. Johnson. Dull offered to buy the car to be Georgia Tech's official mascot. Johnson agreed to sell it for $1,000, but later returned the money as a donation. The Ramblin' Wreck officially became the mascot on May 26, 1961.

James E. Boyd became director of the Engineering Experiment Station in 1957. He believed that research should be combined with education. He involved undergraduate students in his research. Under Boyd, the EES got many electronics contracts. A new Electronics Division was created in 1959, focusing on radar and communications. Boyd also pushed for new research facilities. In 1955, a committee recommended building a research reactor. The $4.5 million Frank H. Neely Research Reactor was finished in 1963 and operated until 1996.

President Harrison also worked to make salaries at Georgia Tech competitive with other schools. The "Joint Tech-Georgia Development Fund" was created in 1967. This fund helped increase faculty salaries at both Georgia Tech and UGA.

Students across the nation protested the Vietnam War. While Tech's student newspaper published articles against the war, the Student Council voted against supporting a protest. There were no protests against the military research at the Georgia Tech Research Institute.

Concerns about the Cambodian Civil War led to the Kent State shootings. This caused about 450 colleges to close. In Georgia, student reactions were mostly calm. All schools in the University System of Georgia closed on May 8 and 9. At Tech, 400 students and faculty held a quiet memorial for Kent State victims.

A 1965 plan started Tech's expansion to what is now West Campus. This area was a working-class neighborhood. In July 1968, Harrison resigned as president. His reasons included changes to campus administration and disagreements with the Board of Regents.

On July 1, 1968, Vernon D. Crawford became dean of the General College. In March 1969, Harrison announced his leave, and Crawford became interim president. During Crawford's time, the School of Industrial Management became a full college. In 1969, Arthur G. Hansen became the institute's next president. He resigned in 1971 to become president of Purdue University.

James E. Boyd was appointed acting president of Georgia Tech in May 1971. He had experience as an administrator and as director of the Engineering Experiment Station. The chancellor hoped Boyd could solve a debate about whether the EES should be fully integrated into Georgia Tech's academic units.

The EES had growing support from Georgia and its Industrial Development Council. However, it relied more and more on federal funding for electronics research. In 1971, both Georgia Tech and the EES faced funding cuts. Boyd's predecessor, Arthur G. Hansen, wanted to fully combine the EES with Georgia Tech's academic units. This would make Tech's research funding look much higher. It would also give Tech access to the EES's reserve fund, which was over $1 million.

Maurice W. Long, the EES director at the time, felt this was against the EES's original purpose. EES employees and business leaders appealed to the Board of Regents and Governor Jimmy Carter (who was a Georgia Tech alumnus). The controversy was covered in the news.

Boyd, as interim president, stopped the plan for complete absorption of the station. But he allowed plans for closer control and more aggressive contract seeking. This included sharing resources and staff more. The EES won new contracts and grants, totaling a record $5.2 million in 1970–1971.

Boyd also faced pressure to fire Yellow Jackets football coach Bud Carson. Alumni were used to success under coaches like John Heisman and Bobby Dodd. Carson's record was 27–27, and the final straw was a 6–6 season in 1971. On January 8, 1972, the Athletic Association board, led by Boyd, voted not to renew Carson's contract. He was the first Georgia Tech coach to be fired. Boyd then announced that Bill Fulcher would be the new head coach.

Georgia Tech's mascot Buzz started in the 1970s. The first Yellow Jacket mascot was Judi McNair, who wore a homemade costume in 1972. She rode on the Ramblin' Wreck and was popular with fans. In 1979, Richie Bland, another student, brought back the idea. He paid for a costume and ran onto the field during a football game. Fans loved it. By 1980, this new mascot was named Buzz Bee and became official. This Buzz character became the model for a new Georgia Tech emblem in 1985.

Research Growth (1972–1987)

Joseph M. Pettit became president of Georgia Tech in 1972. During his 14 years as president, Pettit helped turn Georgia Tech into a top research institution. He also brought Georgia Tech back to its roots of helping Georgia's economy. For decades, research had been tied to NASA and the Department of Defense. Local industrial development had been largely forgotten.

Under Pettit's leadership, Tech's research budget went over $100 million for the first time. Thomas E. Stelson was Tech's vice president for Research from 1974 to 1988. He stressed the importance of both basic and applied research. More focus on research brought more funding for academics. This helped the school's ranking improve. Stelson also reorganized the Georgia Tech Research Institute into eight specialized laboratories.

After the issues with Scientific Atlanta, Georgia Tech's culture didn't really encourage new start-up companies. This changed under Pettit. He had seen the growth of Silicon Valley and wanted something similar in Atlanta. Tech began actively encouraging faculty and students to be entrepreneurial. This was a return to Tech's roots, connecting with the state through groups like the Advanced Technology Development Center.

Pettit also oversaw Georgia Tech joining the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) in 1978. Georgia Tech had left the Southeastern Conference in 1964 and was independent until 1975. The ACC has grown from 8 to 12 members since Tech joined.

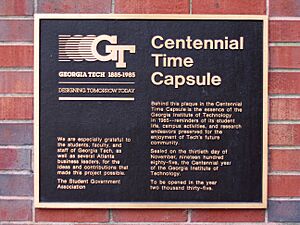

The institute celebrated its centennial (100th birthday) in 1985. Pettit helped lead Tech's $100-million Centennial Campaign. They raised a total of $202.7 million, which was the largest fundraising effort for Georgia Tech at that time. A time capsule was placed in the Student Center. In 1986, Pettit died of cancer. Henry C. Bourne Jr. served as interim president.

Changes and Growth (1987–1994)

President John Patrick Crecine proposed a big change in 1988. At that time, the institute had three colleges: Engineering, Management, and Sciences and Liberal Arts (COSALS). Crecine reorganized the latter two into the College of Computing, the College of Sciences, and the Ivan Allen College of Management, Policy, and International Affairs. Crecine made these changes without asking for much input. Many faculty members disliked his top-down style. The changes passed by a small margin in 1989 and took effect in January 1990. While Crecine was not popular then, his changes are now seen as forward-thinking. He resigned in January 1994.

In October 1990, Tech opened its first overseas campus, Georgia Tech Lorraine (GTL), in France. GTL mainly focuses on graduate education and research. It also has an undergraduate summer program.

Crecine was key in bringing the 1996 Summer Olympics to Atlanta. In 1989, he imagined a grand presentation for the International Olympic Committee (IOC). Tech's Multimedia Laboratory created a 3-D presentation showing a "1996" view of Atlanta. It included digital models of Olympic venues that didn't exist yet. More than 40 Georgia Tech computer scientists helped create this virtual reality tour. Many believe this presentation showed the IOC that Atlanta was serious about its bid. It also helped create Atlanta's high-tech theme for the Games.

After Atlanta won the Olympic bid, a lot of construction happened. Most of what is now "West Campus" was built for Tech to serve as the Olympic Village. New dorms housed athletes and journalists. The Georgia Tech Aquatic Center was built for swimming events, and the Alexander Memorial Coliseum was renovated.

Modern History (1994–Present)

In 1994, G. Wayne Clough became the first Tech alumnus to be president. The 1996 Summer Olympics happened early in his time as president. In 1998, he split the Ivan Allen College, creating the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts and making the College of Management a separate "College" again. During his time, research spending doubled, and student enrollment grew from 13,000 to 18,000. Tech's rankings in U.S. News & World Report also steadily improved.

Clough focused on greatly expanding and modernizing the institute. In 1997, all students were required to own a computer. In 1998, Georgia Tech was the first university in the Southeast to provide internet access to its fraternity and sorority houses. A campus wireless network was set up in 1999 and now covers most of the campus.

In 1999, Georgia Tech started offering degree programs in Southeast Georgia. In 2003, Tech opened a physical campus in Savannah, Georgia, called Georgia Tech Savannah. Clough also focused on more undergraduate research opportunities. He created an "International Plan" degree option, which requires students to study abroad and take international courses. He also started a fund to make Georgia Tech more affordable for students with lower incomes.

The master plan for the school's physical growth was updated twice under Clough, in 1997 and 2002. While Clough was president, about $1 billion was spent on expanding and improving the campus. These projects included new buildings like the Manufacturing Related Disciplines Complex, Tech Square, and the Klaus Advanced Computing Building.

The school has also worked to keep its Historic District. Several projects focused on preserving or improving Tech Tower, the school's oldest building. The area was made more friendly for walkers by removing roads and adding landscaping. The National Register of Historic Places has listed the Georgia Tech Historic District since 1978. In a student survey, "construction" was voted Georgia Tech's worst tradition.

On March 15, 2008, Clough was chosen to lead the Smithsonian Institution. Gary Schuster, Tech's provost, became interim president. On February 9, 2009, George P. "Bud" Peterson became the new president. On April 20, 2010, Georgia Tech was invited to join the Association of American Universities. It was the first new member in nine years.

In 2011, Georgia Tech opened the G. Wayne Clough Undergraduate Learning Commons building, named in his honor. In 2012, Ernest Scheller Jr. gave a $50-million gift, leading to the renaming of the Georgia Tech College of Management to the Scheller College of Business.

On January 7, 2019, Peterson announced he would retire. He was replaced on September 1, 2019, by Ángel Cabrera. Cabrera is an alumnus of the institute and was formerly president of George Mason University. He is the first Spanish-born president of an American university.

Images for kids

-

Nathaniel Edwin Harris, who helped found Georgia Tech, was on its Board of Trustees until he died.

-

Georgia Tech around 1900, with Tech Tower in the background.

-

Grant Field and the east stands around 1912.

-

EES Researcher Jim Hubbard with the EM200 electron microscope.

-

The Three Pioneers, showing Tech's first three African-American students.

-

The Georgia Tech Aquatic Center during the 1996 Summer Olympics.

-

President Emeritus G. Wayne Clough (left) and President G. P. "Bud" Peterson (right) in front of the Ramblin' Wreck at the 2010 groundbreaking of the Clough Undergraduate Learning Commons.

See also

- Georgia Tech traditions

- History of Atlanta

- History of Georgia (U.S. state)

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |