History of Japanese foreign relations facts for kids

The history of Japan's foreign relations tells the story of how Japan interacted with other countries, from around 1850 to 2000. Before the 1850s, Japan was mostly isolated, with only a few contacts through Dutch traders. The Meiji Restoration was a big change that brought new leaders to power. They were eager to learn from Western countries and use their technology and ideas. The government in Tokyo carefully watched and controlled all interactions with outsiders. Japanese groups sent to Europe brought back new ideas that were used across the government and economy. Trade grew quickly as Japan became an industrial nation.

Japan also started to act like European empires, taking over other lands. In the late 1800s, Japan defeated China and gained colonies like Formosa (Taiwan) and Okinawa. The world was amazed by Japan's fast military growth when it defeated Russia in 1904–1905, becoming a recognized world power. Japan continued its expansion, taking control of Korea and moving into Manchuria. Its only military alliance was with Great Britain from 1902 to 1923. In World War I, Japan joined the Allies and took many German lands in the Pacific and China. Japan put a lot of pressure on China, but China resisted.

Even though Japan had a democratic system, the Army slowly gained more control. In the 1930s, parts of the Army in Manchuria largely decided Japan's foreign policy. The League of Nations criticized Japan's takeover of Manchuria in 1931, so Japan left the League. Japan joined the Axis alliance with Germany, but they didn't work closely together until 1943. Japan started a full-scale war in China in 1937, taking over major cities and economic areas. There were many terrible acts against civilians. Two puppet governments were set up in China and Manchuria. Military fights with the Soviet Union didn't go well for Japan, so it looked south instead. Economic pressure from the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands led to a cut-off of vital oil supplies in 1941. Japan declared war and quickly won many battles against the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands, while also continuing the war with China. However, Japan's economy couldn't support such a large war, especially with the fast growth of the American navy. By 1944, Japan was mostly on the defensive. Its plan for a "Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere" fell apart, its navy was sunk, and American bombs started destroying major Japanese cities. The war ended in August 1945 with two American atomic bombs and a Russian invasion. Japan surrendered and was occupied by the Allies, mainly the United States. Its political and economic system was rebuilt to be more democratic, without a military, and with less power for big companies.

Japan was not a major player in global affairs in the late 1940s. But its economy recovered partly because it supplied goods for the Korean War. Japan's foreign policy focused on not getting involved in conflicts, along with very fast growth of its industrial exports. By the 1990s, Japan had the second-largest economy in the world, after the United States. It kept very close ties with the United States, which provided military protection. South Korea, China, and other countries in the Western Pacific traded a lot with Japan, but they still remembered the wartime events.

After the United States, China and Japan have the two largest economies in the 21st century. In 2008, trade between China and Japan reached $266 billion, making them top trading partners. However, historical issues, like the war and disagreements over sea territories, have caused tensions. Despite this, leaders from both countries have tried to improve their relationship. In 2021, Japan hosted the Summer Olympics, winning 27 gold medals and ranking third overall. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, Japan condemned it and put in place sanctions, like freezing assets and banning new investments and high-tech exports. The conflict in Ukraine, along with concerns about China and North Korea, led to a change in Japan's security policy. Japan increased its defense spending and announced a major shift in military policy. It plans to get "counterstrike capabilities" and increase its defense budget to 2% of its GDP by 2027. This change could make Japan the world's third-largest defense spender, after the U.S. and China.

- See also Military history of Japan

Contents

Japan Opens Up to the World (Meiji Restoration)

After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan got a new, strong government. It decided to "gather wisdom from all over the world." Japan started a big plan to change its military, society, politics, and economy. In just one generation, it became a modern country and a major world power. The new leaders knew about Western progress. They sent "learning missions" abroad to learn as much as possible. The Iwakura Mission was the most important. It had 48 members and spent two years (1871–73) traveling through the United States and Europe. They studied everything about modern nations, like governments, courts, schools, businesses, factories, and mines. When they returned, they pushed for changes in Japan to help it catch up with the West.

European powers had forced Japan to sign "unequal treaties" in the 1850s and 1860s. These treaties gave special rights to their citizens in certain port cities. For example, the 1858 Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States, also called the "Harris Treaty," opened several Japanese cities to trade. It also allowed foreign diplomats. It gave extraterritoriality to foreigners, meaning they were judged by their own laws, not Japanese ones. There were also many trade rules that favored Americans. The Dutch, British, and Russians quickly made their own similar treaties, backed by their strong navies. These unequal treaties made Japan feel disrespected, and ending them became a top goal, which was finally achieved in the 1890s.

However, these new treaties also allowed Japan to collect taxes on imports from Europe. These imports grew nine times between 1860 and 1864, and the tax money helped fund the new Meiji government. Exports of Japanese products like tea and silk also grew four times in four years, boosting the local economy. The Meiji leaders wanted Japan to lead Asia, but they knew Japan needed to become strong, build Japanese nationalism among its people, and be careful with potential enemies. They had to learn how to negotiate with experienced Western diplomats. Japan eventually created a group of professional diplomats.

Japan Becomes a World Power

From the 1860s, Japan quickly modernized like Western countries. It built industries, a strong government, and a powerful military. This allowed Japan to expand into Korea, China, Taiwan, and islands to the south. Japan felt it was vulnerable to Western powers unless it took control of nearby areas. It took control of Okinawa and Formosa (Taiwan). Japan's desire to control Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria led to the first Sino-Japanese War with China in 1894–1895 and the Russo-Japanese War with Russia in 1904–1905. The war with China made Japan the first modern imperial power from the East. The war with Russia showed that an Eastern country could defeat a Western one. After these two wars, Japan became the main power in the Far East. It gained influence over southern Manchuria and Korea, which became part of the Japanese Empire in 1910.

Okinawa Island

Okinawa is the largest of the Ryukyu Islands. It had paid tribute to China since the late 1300s. Japan took control of all the Ryukyu Islands in 1609 and officially made them part of Japan in 1879.

War with China (1894-1895)

Problems between China and Japan began in the 1870s over Japan's control of the Ryukyu Islands, competition for power in Korea, and trade issues. Japan had built a strong political and economic system with a small but well-trained army and navy. It easily defeated China in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894. Japanese soldiers committed terrible acts after capturing Port Arthur on the Liaotung Peninsula. In the harsh Treaty of Shimonoseki in April 1895, China recognized Korea's independence. China also gave Formosa (Taiwan), the Pescadores Islands, and the Liaotung Peninsula to Japan. China had to pay a large amount of money, open five new ports to international trade, and allow Japan (and other Western powers) to build factories in these cities. However, Russia, France, and Germany felt they were losing out. In the Triple Intervention, they forced Japan to return the Liaotung Peninsula in exchange for more money from China. The only good result for China was that these factories helped industrialize its cities, creating local business owners and skilled workers.

Taiwan: Japan's First Colony

The island of Formosa (Taiwan) had native people when Dutch traders arrived in 1623. The Dutch East India Company built Fort Zeelandia to trade with Japan and China. They soon started ruling the native people. China took control in the 1660s and sent settlers. By the 1890s, there were about 2.3 million Chinese and 200,000 native people. After Japan's victory in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894–95, the peace treaty gave the island to Japan. It became Japan's first colony.

Japan hoped to gain many benefits from Taiwan, but it got fewer than expected. Japan knew its home islands had limited resources. It hoped Taiwan, with its rich farmlands, would help with this shortage. By 1905, Taiwan was producing rice and sugar and even made a small profit for Japan. Perhaps more importantly, Japan gained respect across Asia for being the first non-European country to run a modern colony. Japan learned how to adapt its German-style government rules to real-life conditions and how to handle frequent rebellions. The main goal was to spread Japanese language and culture. But the administrators realized they first had to understand the Chinese culture of the people. Japan saw itself as having a "civilizing mission." It opened schools so that farmers could become productive and loyal workers. Medical facilities were modernized, and the death rate dropped. To keep order, Japan set up a strict police system that watched everyone closely. In 1945, Japan lost its empire, and Taiwan was returned to China.

War with Russia (1904–1905)

In 1895, Japan felt cheated out of its victory spoils over China by Western Powers (including Russia), who changed the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901 saw Japan and Russia as allies fighting together against the Chinese.

In the 1890s, Japan was angry about Russia moving into its plans for influence in Korea and Manchuria. Japan offered to let Russia control Manchuria if Russia recognized Korea as Japan's area of influence. Russia refused and wanted Korea north of the 39th parallel to be a neutral zone between them. The Japanese government decided on war to stop what it saw as a Russian threat to its expansion plans in Asia. After talks failed in 1904, the Japanese Navy attacked the Russian fleet at Port Arthur, China, in a surprise attack. Russia suffered many defeats. Tsar Nicholas II kept fighting, hoping Russia would win big naval battles. When that didn't happen, he fought to save Russia's honor and avoid a "humiliating peace." The war ended with the Treaty of Portsmouth, arranged by US President Theodore Roosevelt. Japan's complete military victory surprised the world. This changed the balance of power in East Asia and showed Japan's new importance on the world stage. It was the first major modern military victory of an Asian power over a European one.

Taking Over Korea

In 1905, Japan and Korea signed the Eulsa Treaty. This treaty made Korea a Japanese protectorate, meaning Japan controlled its foreign affairs. This was a result of Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War and its desire to strengthen its hold on the Korean Peninsula. The Eulsa Treaty led to the 1907 Treaty two years later. The 1907 Treaty made sure Korea would follow a Japanese resident general, and Japan would control Korea's internal matters. Korean Emperor Gojong was forced to step down in favor of his son, Sunjong, because he protested Japan's actions at the Hague Conference. Finally, in 1910, the Annexation Treaty was signed, officially making Korea part of Japan.

Important Leaders in Japan's Foreign Policy

Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi

Prince Itō Hirobumi (1841–1909) was prime minister for most of the time between 1885 and 1901. He was very important in shaping Japan's foreign policy. He made stronger diplomatic ties with Western powers like Germany, the United States, and especially Great Britain through the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1905. In Asia, he oversaw the short, successful war against China (1894–95). He negotiated China's surrender on terms that were very good for Japan. These included taking over Taiwan and freeing Korea from China's control. He also gained control of the Liaodong Peninsula with Darien and Port Arthur. But Russia, Germany, and France worked together in the Triple Intervention and immediately forced Japan to give that land back to China.

In the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation of 1894, he successfully removed some of the unfair treaty rules that had bothered Japan since the Meiji period began. His biggest success was the Anglo-Japanese Alliance signed in 1902. This was a major diplomatic event, ending Britain's policy of "splendid isolation." The alliance was renewed and expanded twice, in 1905 and 1911, before ending in 1923.

Itō wanted to avoid a Russo-Japanese War. He proposed a policy called Man-Kan kōkan – giving Manchuria to Russia's control in exchange for Russia accepting Japan's control over Korea. He traveled to the United States and Europe, going to Saint Petersburg in November 1901. But he couldn't find a compromise with Russian leaders. Soon, the government of Katsura Tarō decided to stop trying for Man-Kan kōkan, and tensions with Russia grew, leading to war.

Prime Minister Katsura Tarō

Prince Katsura Tarō (1848–1913) was prime minister three times between 1901 and 1911. During his first term (1901–1906), Japan became a major imperial power in East Asia. This period included the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 and victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. During his time, the Taft–Katsura agreement with the U.S. recognized Japan's control over Korea. His second term (1908–1911) was important for the Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty of 1910.

Prince Tokugawa Iesato

Prince Tokugawa Iesato (1863-1940) was a very important diplomatic representative for Japan in international relations during the early 1900s. He and his supporters worked for peace and democracy. Prince Tokugawa represented Japan at the Washington Naval Conference, where he promoted a treaty to limit naval weapons.

Japan in the Early 20th Century (1910–1941)

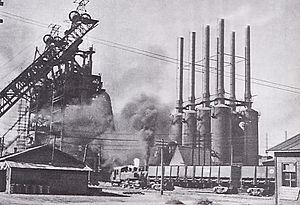

Japan copied the most advanced European countries for its industrial economy. They started with textiles, railways, and shipping, then moved to electricity and machinery. A big weakness was a lack of raw materials. Industry ran short of copper, and Japan even had to import coal. A serious problem with Japan's aggressive military expansion was its heavy reliance on imports. For example, Japan depended on imports for 100% of its aluminum, 85% of its iron ore, and 79% of its oil. It was one thing to go to war with China or Russia, but quite another to be in conflict with key suppliers of raw materials like the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands, who provided most of Japan's oil and iron.

World War I and Japan's Role

Japan joined the Allies in World War I, hoping to gain territory after the victory. Japan made small territorial gains by taking over Germany's scattered possessions in the Pacific and China for the Allies. However, the Allied countries strongly resisted Japan's attempt to control China through the Twenty-One Demands of 1915. Japan's occupation of Siberia didn't achieve much. Japan's diplomacy and limited military actions during the war had few long-term results. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Japan's request for recognition of racial equality among the winning countries was rejected. After the war, Japan became more isolated diplomatically. The 1902 alliance with Britain was not renewed in 1922 because of strong pressure on Britain from Canada and the United States.

In the 1920s, Japanese diplomacy was based on a mostly democratic political system and favored working with other countries. But by the mid-1930s, Japan was quickly changing. It rejected democracy at home as the Army gained more and more power. It also rejected international cooperation. By the late 1930s, Japan was building closer ties with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

Japan put heavy pressure on China in 1915, especially with the Twenty-One Demands. The U.S. helped China push back, which lessened the pressure. As Russia's pro-Allied government collapsed into civil wars, the Allies sent troops into Russian territory to support anti-Communist groups. The United States sent 8,000 troops to Siberia, and Japan sent 80,000. Japan's goal was less about helping the Allies and more about taking control of the Trans-Siberian Railroad and nearby areas, which would give it huge control over Manchuria. The Americans, who originally wanted to help Czechoslovakian prisoners escape, increasingly found themselves watching and blocking Japanese expansion. Both nations withdrew their troops in 1920, as Lenin's Bolsheviks took firm control of Russia.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Japan was given control over several small islands and territories that had belonged to the German Empire. Japan was disappointed when its proposal to condemn racism in international affairs was removed from the agenda. However, its main demand, which it pursued strongly, was to get permanent control of Germany's holdings in Shantung, China, which Japan had captured early in the war. China protested angrily but had little power. The Shandong Problem seemed like a Japanese victory at first. But Tokyo soon had second thoughts as widespread protests inside China led to the May Fourth Movement by angry students. Finally, in 1922, with help from the U.S. and Great Britain, Japan was forced to return Shantung to China.

Japan in the 1920s

A kind of friendly relationship developed between Washington and Tokyo, even though they had different ideas. The Japanese focused on traditional power diplomacy, emphasizing control over specific areas of influence. The United States followed Wilsonianism, based on the "open door" policy and international cooperation. Both sides made compromises and were successful in diplomatic efforts, like the naval limitations at the Washington conference in 1922. The conference set a naval ratio for large warships of 5:5:3 among the United States, Britain, and Japan. This slowed down the naval arms race for ten years. Japan was upset by the racism in the 1924 American immigration laws, which reduced the long-standing Japanese quota of 100 immigrants per year to zero. Japan was also annoyed by similar rules in Canada and Australia. Britain, responding to anti-Japanese feelings in its Commonwealth countries and the United States, did not renew its twenty-year-old treaty with Japan in 1923.

In 1930, the London disarmament conference angered the Japanese Army and Navy. Japan's navy demanded to be equal with the United States and Britain, but this was rejected, and the conference kept the 1921 ratios. Japan was required to scrap a large warship. Extremists assassinated Japan's prime minister, and the military gained more power, leading to a quick decline in democracy.

Japan Takes Over Manchuria (1931)

In September 1931, the Japanese Army, acting on its own without government approval, took control of Manchuria. This area had not been controlled by China for decades. The Army set up a puppet government called Manchukuo. Britain and France supported a League of Nations investigation. The Lytton Report in 1932 said that Japan had real complaints but acted illegally by taking the whole province. Japan left the League, and Britain took no action. The United States issued the Stimson Doctrine, saying it would not recognize Japan's conquest as legal. The immediate impact was small, but it set the stage for American support for China against Japan in the late 1930s.

The civilian government in Tokyo tried to downplay the Army's actions in Manchuria and announced it was pulling out. Instead, the Army finished conquering Manchuria, and the civilian government resigned. The political parties were divided on military expansion. The new Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi tried to negotiate with China, but he was assassinated in the May 15 Incident in 1932. This event started an era of extreme nationalism led by the Army and supported by patriotic groups. It ended civilian rule in Japan until after 1945.

However, the Army itself was divided into groups with different ideas. One group saw the Soviet Union as the main enemy, while another wanted to build a large empire in Manchuria and northern China. The Navy, though smaller, also had its own divisions. Large-scale warfare, known as the Second Sino-Japanese War, began in August 1937. Naval and infantry attacks focused on Shanghai, then quickly spread to other major cities. There were many terrible acts against Chinese civilians, like the Nanking Massacre in December 1937. By 1939, military lines had settled, with Japan controlling almost all major Chinese cities and industrial areas. A puppet government was set up. Meanwhile, the Japanese Army did poorly in big battles with Soviet forces in Mongolia at Battles of Khalkhin Gol in summer 1939. The USSR was too powerful. Tokyo and Moscow signed a non-aggression treaty in April 1941. The military leaders then turned their attention to the European colonies to the south, which had urgently needed oil fields.

The Army's Growing Power (1919–1941)

The Army increasingly took control of the government. They assassinated opposing leaders, suppressed left-wing groups, and pushed for a very aggressive foreign policy toward China. Japan's policy angered the United States, Britain, France, and the Netherlands. Japanese nationalism was the main driving force, along with a dislike for democracy. Extreme right-wing ideas became powerful throughout the Japanese government and society, especially within the Kwantung Army, which was stationed in Manchuria along the Japanese-owned South Manchuria Railroad. During the Manchurian Incident of 1931, radical army officers conquered Manchuria from local officials and set up the puppet government of Manchukuo there without permission from the Japanese government. International criticism of Japan after the invasion led to Japan leaving the League of Nations.

Japan's plans for expansion grew bolder. Many of Japan's political leaders wanted Japan to gain new territory for resources and to settle its extra population. These ambitions led to the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. After their victory in the Chinese capital, the Japanese military committed the terrible Nanking Massacre. The Japanese military failed to destroy the Chinese government led by Chiang Kai-shek, which moved to remote areas. The conflict was a stalemate that lasted until 1945. Japan's war aim was to create the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a huge pan-Asian union led by Japan. Emperor Hirohito's role in Japan's foreign wars is still debated. Some historians see him as a powerless figurehead, while others see him as supporting Japanese militarism. The United States became increasingly worried about the Philippines, an American colony close to Japan, and started looking for ways to stop Japanese expansion.

World War II and Japan

American public opinion and leaders, even those who wanted to stay out of foreign conflicts, strongly opposed Japan's invasion of China in 1937. President Roosevelt put more and more strict economic sanctions on Japan. These were meant to cut off the oil and steel Japan needed to continue its war in China. Japan reacted by forming an alliance with Germany and Italy in 1940, called the Tripartite Pact, which made its relations with the US worse. In July 1941, the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands froze all Japanese assets and stopped oil shipments. Japan had very little oil of its own.

Japan had conquered all of Manchuria and most of coastal China by 1939. But the Allies refused to recognize these conquests and increased their support for China. President Franklin Roosevelt arranged for American pilots and ground crews to set up a strong Chinese Air Force, nicknamed the Flying Tigers. This force would not only defend against Japanese air power but also start bombing the Japanese islands.

Diplomacy offered little room to solve the big differences between Japan and the United States. The United States was strongly committed to defending China's independence. The desire to stay out of war in Europe, which many Americans felt, did not apply to Asia. Japan had no friends in the United States, Great Britain, or the Netherlands. The United States had not yet declared war on Germany, but it was working closely with Britain and the Netherlands about the Japanese threat. The United States started moving its newest B-17 heavy bombers to bases in the Philippines, which were close enough to reach Japanese cities. The goal was to stop any Japanese attacks to the south. Also, plans were well underway to send American air forces to China, where American pilots in Chinese uniforms were preparing to bomb Japanese cities even before Pearl Harbor. Great Britain knew it couldn't defend Hong Kong, but it was confident in its ability to defend its main base in Singapore and the surrounding Malaya Peninsula. When the war started in December 1941, Australian soldiers were rushed to Singapore. Weeks later, Singapore surrendered, and all Australian and British forces were sent to prisoner of war camps. The Netherlands, whose home country was taken over by Germany, had a small Navy to defend the Dutch East Indies. Their role was to delay the Japanese invasion long enough to destroy the oil wells, drilling equipment, refineries, and pipelines that were Japan's main target.

Decisions in Tokyo were controlled by the Army, and then approved by Emperor Hirohito. The Navy also had a say. However, the civilian government and diplomats were mostly ignored. The Army saw conquering China as its main mission. But operations in Manchuria had created a long border with the Soviet Union. Large military clashes with Soviet forces at Nomonhan in summer 1939 showed that the Soviets had much stronger military power. Even though it would help Germany's war against Russia after June 1941, the Japanese army refused to go north. The Japanese realized they urgently needed oil. Over 90% of their oil came from the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands. From the Army's point of view, a secure fuel supply was essential for warplanes, tanks, trucks, and, of course, the Navy's warships and warplanes. The solution was to send the Navy south to seize the oilfields in the Dutch East Indies and nearby British colonies. Some admirals and many civilians, including Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro, believed that a war with the U.S. would end in defeat. The alternative was to lose honor and power.

While the admirals also doubted their long-term ability to fight the American and British navies, they hoped that a surprise attack destroying the American fleet at Pearl Harbor would bring the enemy to the negotiating table for a good outcome. Japanese diplomats were sent to Washington in summer 1941 for high-level talks. However, they did not represent the Army leaders who made the decisions. By early October, both sides realized that no compromises were possible between Japan's commitment to conquer China and America's commitment to defend China. Japan's civilian government fell, and the Army took full control, determined to go to war.

Japan's Imperial Conquests

Japan launched several quick wars in East Asia, and they all succeeded. In 1937, the Japanese Army invaded and captured most of the coastal Chinese cities like Shanghai. Japan took over French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia) in 1940–41. After declaring war on the U.S., Britain, and the Netherlands in December 1941, it quickly conquered British Malaya (Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore) as well as the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). Thailand managed to stay independent by becoming a satellite state of Japan. From December 1941 to May 1942, Japan sank major parts of the American, British, and Dutch fleets. It captured Hong Kong, Singapore, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies. It reached the borders of India and began bombing Australia. Japan had suddenly achieved its goal of ruling the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

How Japan Ruled Its Empire

The ideas behind Japan's colonial empire, as it grew hugely during the war, had two conflicting goals. On one hand, it preached the unity of the Co-Prosperity Sphere. This was supposed to be a group of Asian peoples, led by Japan, against Western imperialism. This idea praised the spiritual values of the East against the "greedy" materialism of the West. In reality, it was a nice-sounding name for taking land and getting important natural resources. The Japanese put organized government workers and engineers in charge of their new empire. They believed in efficiency, modernization, and using engineering to solve social problems.

Economist Akamatsu Kaname (1896–1974) created the "Flying geese paradigm" in the late 1930s. This was a model for how the empire's economy would work. Japan (the lead goose) would focus on high-tech, high-value manufacturing. It would buy food, cotton, and iron ore at very low prices from the other Co-Prosperity Sphere countries (the trailing geese). Then, it would sell them expensive finished products like chemicals, fertilizers, and machinery. These dealings were done by powerful zaibatsu corporations and watched over by the Japanese government. The Flying geese paradigm was used again after 1950 and was credited for the fast economic growth of Japan's East Asian trading partners.

The Imperial Japanese Army ran harsh governments in most of the conquered areas. But they paid more attention to the Dutch East Indies. The main goal was to get oil. Japan supported an Indonesian nationalist movement led by Sukarno. Sukarno eventually came to power in the late 1940s after fighting the Dutch for several years. The Dutch destroyed their oil wells, but the Japanese reopened them. However, most of the tankers carrying oil to Japan were sunk by American submarines, so Japan's oil shortage became very serious.

Puppet States in China

Japan set up puppet governments in Manchuria ("Manchukuo") and in China itself. These governments disappeared at the end of the war.

Manchuria, the historic home of the Manchu dynasty, was not clearly controlled after 1912. It was run by local warlords. The Japanese Army took control in 1931 and set up a puppet state called Manchukuo in 1932 for its 34 million people. Other areas were added, and over 800,000 Japanese moved in as administrators. The official ruler was Puyi, who as a small child had been the last Emperor of China. He was removed from power during the 1911 revolution, and now the Japanese brought him back in a powerless role. Only Axis countries recognized Manchukuo. The United States in 1932 announced the Stimson Doctrine, stating that it would never recognize Japanese control. Japan modernized the economy and ran it as a satellite to the Japanese economy. It was out of range of American bombers, so its factories grew and kept producing until the end of the war. Manchukuo was returned to China in 1945. When Japan took control of China itself in 1937–38, the Japanese Central China Expeditionary Army set up the Reorganized National Government of China, a puppet state, under the leadership of Wang Ching-wei (1883–1944). It was based in Nanjing. The Japanese were in full control. The puppet state declared war on the Allies in 1943. Wang was allowed to manage the International Settlement in Shanghai. The puppet state had an army of 900,000 soldiers and was positioned against the Nationalist army under Chiang Kai-shek. It did little fighting.

Japan After World War II (1945–1990s)

American Occupation of Japan

Americans, led by General Douglas MacArthur, were in charge of Japan from 1945 to 1951. Other Allied countries and former Japanese colonies wanted revenge. But MacArthur ran a very fair system. Harsh actions were limited to war criminals, who were tried and punished. Japan lost its independence and had no diplomatic relations. Its people were not allowed to travel abroad. MacArthur worked to make Japan more democratic, similar to the American New Deal. This meant getting rid of militarism and big companies that controlled everything. It also meant teaching democratic values and how to vote. MacArthur worked well with Emperor Hirohito, who stayed on the throne as a symbolic ruler. In practice, the Japanese themselves handled the actual government, led by Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru. His policy, known as the Yoshida Doctrine, was to focus Japan's efforts on rebuilding its economy. Japan would rely entirely on the United States for defense and foreign policy. Yoshida shared and carried out MacArthur's goals to make Japanese political, social, and economic systems democratic, while completely removing the military and rejecting its past militaristic ways.

MacArthur ordered a small rearmament of Japan the week after the Korean War broke out in June 1950. He called for a national police reserve of 75,000 men, separate from the existing 125,000 police force. The Coast Guard grew from 10,000 to 18,000. The idea that these were police forces for internal use won out over objections from anti-military groups. However, Washington saw them as a quasi-military force that would use military equipment loaned from the United States. Japan now had a small army of its own. Japan became the supply base for American and allied forces fighting in Korea. A surge in orders for goods and services jump-started Japan's economy.

The occupation ended with the Peace Treaty of 1951, signed by Japan, the United States, and 47 other nations. The Soviet Union and neither Chinese government signed it. The occupation officially ended in April 1952. American diplomat John Foster Dulles was in charge of writing the peace treaty. He had been deeply involved in 1919 when harsh demands and a "guilt clause" were put on Germany at the Paris Peace Conference. Dulles thought that was a terrible mistake that helped extreme right-wing groups and the Nazis in Germany. He made sure it didn't happen again. So, Japan was not forced to pay reparations to anyone.

"Economic Miracle" of the 1950s

From 1950 onward, Japan rebuilt itself politically and economically. The U.S. and its allies used Japan as their supply base during the Korean War (1950–53), which poured money into the economy. Historian Yone Sugita notes that "the 1950s was a decade during which Japan created a unique corporate capitalist system where government, business, and labor worked closely together."

Japan's new economic power soon gave it much more influence than it ever had militarily. The Yoshida Doctrine and the Japanese government's economic involvement led to an economic miracle, similar to West Germany's a few years earlier. The Japanese government worked to boost industrial development through a mix of protecting its own industries and expanding trade. The creation of the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) was key to Japan's post-war economic recovery. By 1954, the MITI system was fully in effect. It coordinated industry and government actions, encouraged cooperation, and supported research to develop promising exports and find substitutes for imports (especially dyes, iron and steel, and soda ash). Yoshida's successor, Hayato Ikeda, started economic policies that removed many of Japan's anti-monopoly laws. Foreign companies were kept out of the Japanese market, and strict protectionist laws were put in place.

Meanwhile, the United States, under President Eisenhower, saw Japan as the economic anchor for Western Cold War policy in Asia. Japan was completely demilitarized and did not contribute military power, but it provided economic power. The US and UN forces used Japan as their forward supply base during the Korean War (1950–53), and orders for supplies flooded Japan. The close economic relationship strengthened political and diplomatic ties. This helped the two nations survive a political crisis in 1960 involving left-wing opposition to the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. The left failed to force the removal of large American military bases in Japan, especially on Okinawa. Shimizu argues that the American policy of creating "people of plenty" was a success in Japan and achieved its goal of stopping anti-capitalist protests from the left.

In 1968, Japan's economy surpassed West Germany to become the second-largest economic power in the world after the United States. Japan became a great power again. It held the position of the second-biggest economy until 2011, when the economy of China surpassed it.

Japan's handling of its war history caused tension with China and Korea. Japanese officials and emperors have made over 50 formal war apologies since the 1950s. However, some politicians in China and Korea found the official apologies, such as those from the Emperor in 1990 and the Murayama Statement of 1995, to be not enough or not sincere. Nationalist politics have made this worse, such as denial of the Nanjing Massacre and other war crimes, and history textbooks that change the past. These issues caused protests in East Asia. Japanese politicians often visit Yasukuni Shrine to honor those who died in wars from 1868 to 1954. However, convicted war criminals are also honored there.

Recent History (Since 2000)

The Chinese and Japanese economies are the world's second and third-largest economies by nominal GDP respectively. They are also the first and fourth-largest economies by GDP PPP. In 2008, trade between China and Japan grew to $266.4 billion, a 12.5 percent rise from 2007, making them top trading partners. China was also the biggest buyer of Japanese exports in 2009. Since the end of World War II, relations between China and Japan are still affected by political disagreements. The tension between these two countries comes from the history of the Japanese war, imperialism, and disputes over sea territories in the East China Sea. So, even though these two nations are close business partners, there is an underlying tension that leaders on both sides are trying to calm. Chinese and Japanese leaders have met several times to try to build a friendly relationship between the two countries.

In 2020, Tokyo was supposed to host the Summer Olympics for the second time since 1964. Japan was the first Asian country to host the Olympics twice. However, because of the global COVID-19 pandemic and its economic impact, the Summer Olympics were postponed to 2021. They took place from July 23 to August 8, 2021. Japan ranked third, winning 27 gold medals.

On December 16, 2022, Japan announced a major change in its military policy. It plans to get "counterstrike capabilities" and increase its defense budget to 2% of its GDP (¥43 trillion, or about $315 billion) by 2027. This change is driven by regional security concerns about China, North Korea, and Russia. This will make Japan jump from ninth to the world's third-largest defense spender, behind the United States and China.

See also

- History of Japan

- Causes of World War II

- Cold War

- History of Sino-Japanese relations, China

- France–Japan relations

- Germany–Japan relations

- Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, 1930–1945

- History of Japan–Korea relations

- Japanese foreign policy on Southeast Asia

- Empire of Japan–Russian Empire relations to 1917

- Japan–Soviet Union relations, 1917–1991

- Japan–Russia relations, since 1991

- Japan–United Kingdom relations

- Japan–United States relations

Images for kids

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |