Battles of Khalkhin Gol facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battles of Khalkhin Gol/Nomonhan |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Soviet–Japanese border conflicts | |||||||||

Japanese infantrymen near wrecked USSR armored vehicles, July 1939 |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

61,860–73,961

4,000 trucks 1,921 horses and camels (Mongol only) |

~20,000–30,000

1,000 trucks 2,708 horses |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Manpower: Equipment: 208 aircraft lost 253 tanks destroyed or crippled 133 armored cars destroyed 96 mortars and artillery 49 tractors and prime movers 652 trucks and other motor vehicles significant animal casualties |

Manpower: Equipment: 162 aircraft lost 29 tanks destroyed or crippled 7 tankettes destroyed 72 artillery pieces (field guns only) 2,330 horses killed, injured, or sick significant motor vehicle losses |

||||||||

- Revolutions of 1917–1923

- Aftermath of World War I 1918–1939

- Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War 1918–1925

- Province of the Sudetenland 1918–1920

- 1918–1920 unrest in Split

- Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919

- Heimosodat 1918–1922

- Austro-Slovene conflict in Carinthia 1918–1919

- Hungarian–Romanian War 1918–1919

- Hungarian–Czechoslovak War 1918–1919

- 1919 Egyptian Revolution

- Christmas Uprising 1919

- Irish War of Independence 1919

- Comintern World Congresses 1919–1935

- Treaty of Versailles 1919

- Shandong Problem 1919–1922

- Polish–Soviet War 1919–1921

- Polish–Czechoslovak War 1919

- Polish–Lithuanian War 1919–1920

- Silesian Uprisings 1919–1921

- Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1919

- Turkish War of Independence 1919–1923

- Venizelos–Tittoni agreement 1919

- Italian Regency of Carnaro 1919–1920

- Iraqi Revolt 1920

- Treaty of Trianon 1920

- Treaty of Rapallo 1920

- Little Entente 1920–1938

- Treaty of Tartu (Finland–Russia) 1920–1938

- Mongolian Revolution of 1921

- Soviet intervention in Mongolia 1921–1924

- Franco-Polish alliance 1921–1940

- Polish–Romanian alliance 1921–1939

- Genoa Conference (1922)

- Treaty of Rapallo (1922)

- March on Rome 1922

- Sun–Joffe Manifesto 1923

- Corfu incident 1923

- Occupation of the Ruhr 1923–1925

- Treaty of Lausanne 1923–1924

- Mein Kampf 1925

- Second Italo-Senussi War 1923–1932

- First United Front 1923–1927

- Dawes Plan 1924

- Treaty of Rome (1924)

- Soviet–Japanese Basic Convention 1925

- German–Polish customs war 1925–1934

- Treaty of Nettuno 1925

- Locarno Treaties 1925

- Anti-Fengtian War 1925–1926

- Treaty of Berlin (1926)

- May Coup (Poland) 1926

- Northern Expedition 1926–1928

- Nanking incident of 1927

- Chinese Civil War 1927–1937

- Jinan incident 1928

- Huanggutun incident 1928

- Italo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1928

- Chinese reunification 1928

- Lateran Treaty 1928

- Central Plains War 1929–1930

- Young Plan 1929

- Sino-Soviet conflict (1929)

- Great Depression 1929

- London Naval Treaty 1930

- Kumul Rebellion 1931–1934

- Japanese invasion of Manchuria 1931

- Pacification of Manchukuo 1931–1942

- January 28 incident 1932

- Soviet–Japanese border conflicts 1932–1939

- Geneva Conference 1932–1934

- May 15 incident 1932

- Lausanne Conference of 1932

- Soviet–Polish Non-Aggression Pact 1932

- Soviet–Finnish Non-Aggression Pact 1932

- Proclamation of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 1932

- Defense of the Great Wall 1933

- Battle of Rehe 1933

- Nazis' rise to power in Germany 1933

- Reichskonkordat 1933

- Tanggu Truce 1933

- Italo-Soviet Pact 1933

- Inner Mongolian Campaign 1933–1936

- Austrian Civil War 1934

- Balkan Pact 1934–1940

- July Putsch 1934

- German–Polish declaration of non-aggression 1934–1939

- Baltic Entente 1934–1939

- 1934 Montreux Fascist conference

- Stresa Front 1935

- Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance 1935

- Soviet–Czechoslovakia Treaty of Mutual Assistance 1935

- He–Umezu Agreement 1935

- Anglo-German Naval Agreement 1935

- December 9th Movement

- Second Italo-Ethiopian War 1935–1936

- February 26 incident 1936

- Remilitarization of the Rhineland 1936

- Soviet-Mongolian alliance 1936

- Spanish Civil War 1936–1939

- Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936

- Italo-German "Axis" protocol 1936

- Anti-Comintern Pact 1936

- Suiyuan campaign 1936

- Xi'an Incident 1936

- Second Sino-Japanese War 1937–1945

- USS Panay incident 1937

- Anschluss Mar. 1938

- 1938 Polish ultimatum to Lithuania Mar. 1938

- Easter Accords April 1938

- May Crisis May 1938

- Battle of Lake Khasan July–Aug. 1938

- Salonika Agreement July 1938

- Bled Agreement Aug. 1938

- Undeclared German–Czechoslovak War Sep. 1938

- Munich Agreement Sep. 1938

- First Vienna Award Nov. 1938

- German occupation of Czechoslovakia Mar. 1939

- Hungarian invasion of Carpatho-Ukraine Mar. 1939

- German ultimatum to Lithuania Mar. 1939

- Slovak–Hungarian War Mar. 1939

- Final offensive of the Spanish Civil War Mar.–Apr. 1939

- Danzig crisis Mar.–Aug. 1939

- British guarantee to Poland Mar. 1939

- Italian invasion of Albania Apr. 1939

- Soviet–British–French Moscow negotiations Apr.–Aug. 1939

- Pact of Steel May 1939

- Battles of Khalkhin Gol May–Sep. 1939

- Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact Aug. 1939

- Invasion of Poland Sep. 1939

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (Russian: Бои на Халхин-Голе; Mongolian: Халхын голын байлдаан) were important battles in 1939. They were part of a larger conflict between the Soviet Union and Japan over their borders. These battles also involved Mongolia, which was allied with the Soviet Union, and Manchukuo, which was controlled by Japan.

The fighting happened near the Khalkhin Gol river. In Japan, this event is known as the Nomonhan Incident (ノモンハン事件, Nomonhan jiken), named after a nearby village. The battles ended with the Japanese Sixth Army being defeated.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

After Japan took over a region called Manchuria in 1931, they started looking at Soviet lands nearby. The first big clash between Soviet and Japanese forces happened in 1938. Smaller fights often broke out along the border of Manchuria.

In 1939, Manchuria was a state controlled by Japan, called Manchukuo. Mongolia was a communist state allied with the Soviet Union, known as the Mongolian People's Republic. Japan believed the border was the Khalkhin Gol river. But Mongolia and the Soviets said the border was about 16 kilometres (10 mi) east of the river, near Nomonhan village. This disagreement over the border led to the battles.

The main Japanese army in Manchukuo was the Kwantung Army. It had some of Japan's best soldiers. However, the western part of Manchukuo was guarded by the newer and less experienced 23rd Infantry Division. This division was led by General Michitarō Komatsubara and had older equipment.

The Soviet forces were from the 57th Special Corps. They were in charge of protecting the border between Siberia and Manchuria. Mongolian troops were mostly cavalry (soldiers on horseback) and light artillery (cannons). They were fast and effective but didn't have many armored vehicles or enough soldiers.

On June 2, 1939, Georgy Zhukov was sent to Mongolia. His job was to take command of the Soviet forces and stop the Japanese attacks. The Japanese government had told the Kwantung Army to make Manchukuo's borders stronger. But the Kwantung Army often acted on its own, sometimes even against orders from Tokyo.

The Battles Begin

May: Small Fights Start

The fighting started on May 11, 1939. A group of Mongolian cavalry entered the disputed area to find grazing land for their horses. Manchu cavalry attacked them and pushed them back across the Khalkhin Gol river. On May 13, the Mongolians returned with more soldiers, but the Manchukoans could not push them out.

On May 14, a Japanese officer, Lt. Col. Yaozo Azuma, led his troops into the area. The Mongolians pulled back. But Soviet and Mongolian forces soon returned. Azuma's group tried to remove them again, but on May 28, the Soviet-Mongolian forces surrounded Azuma's group and destroyed it. The Azuma force lost many soldiers.

The Soviet forces were led by Komandarm Grigori Shtern from May 1938.

June: More Troops Arrive

Both sides sent more soldiers to the area. Japan soon had 30,000 men there. The Soviets sent a new commander, Comcor Georgy Zhukov, who arrived on June 5. He brought more motorized and armored vehicles to the battle zone. Comcor Yakov Smushkevich came with his air force units. J. Lkhagvasuren, a Mongolian army leader, became Zhukov's helper.

On June 27, the Japanese Army Air Force attacked the Soviet airbase at Tamsak-Bulak in Mongolia. The Japanese won this air battle. However, the Kwantung Army had ordered this attack without permission from Tokyo. To stop the fighting from getting bigger, Tokyo quickly ordered the Japanese air force not to attack Soviet airbases anymore.

Throughout June, there were reports of Soviet and Mongolian activity on both sides of the river. Small attacks happened on isolated Manchukuo units. By the end of June, the Japanese commander, Lt. Gen. Michitarō Komatsubara, got permission to "expel the invaders."

July: Japanese Attack

The Japanese planned a two-part attack. The first part involved several infantry regiments. They would cross the Khalkhin Gol, clear out Soviet forces on Baintsagan Hill, and then move south. The second part was for the Japanese 1st Tank Corps. This group had many tanks and would attack Soviet troops on the east side of the river. The two Japanese groups planned to meet up.

- Lt. Gen. Yasuoka Masaomi, Japanese Army, Commander of 1st Tank Corps

- 3rd Tank Regiment

- Type 89 I-Go medium tanks – 26

- Type 97 Chi-Ha medium tanks – 4

- Type 94 tankettes – 7

- Type 97 Te-Ke tankettes – 4

- 4th Tank Regiment

- Type 95 Ha-Go light tanks – 35

- Type 89 I-Go medium tanks – 8

- Type 94 tankettes – 3

- 3rd Tank Regiment

The northern Japanese force crossed the river and pushed the Soviets off Baintsagan Hill. But Zhukov saw the danger and launched a counterattack with 450 tanks and armored cars. These Soviet armored vehicles, mostly BT-5 and BT-7 tanks and BA-10 and BA-3/6 armored cars, attacked the Japanese from three sides. They almost surrounded the Japanese. The Japanese had only one bridge for supplies and had to retreat back across the river on July 5.

Meanwhile, the Japanese 1st Tank Corps attacked on the night of July 2. They moved in the dark to avoid Soviet cannons. A fierce battle followed. The Japanese tank force lost more than half its vehicles but could not break through Soviet lines. After a Soviet counterattack on July 9, the Japanese tank force was pushed back and its commander was removed.

For the next two weeks, both armies continued to fight along the river. Zhukov's army was 748 km (465 mi) from its supply base. He used 2,600 trucks to bring supplies to his troops. The Japanese, however, had big supply problems because they didn't have enough trucks.

On July 23, the Japanese launched another large attack. They used a huge amount of artillery fire, using up more than half their ammunition in two days. The attack made some progress but failed to break through Soviet lines. The Japanese stopped their attack on July 25 because they had too many casualties and not enough artillery supplies. By this point, they had lost over 5,000 soldiers. Soviet losses were higher but they could replace them more easily. The battle then became a stalemate.

August: Soviet Counterattack

With war possibly starting in Europe, Zhukov planned a major attack for August 20, 1939. He wanted to push the Japanese out of the Khalkhin Gol area and end the fighting. Zhukov used at least 4,000 trucks to bring supplies from his base, 600 km (370 mi) away. He gathered a strong force of three tank brigades and two mechanized brigades (armored cars with infantry). This force was placed on the Soviet left and right sides.

The entire Soviet force included three infantry divisions, two tank divisions, and two more tank brigades (about 498 BT-5 and BT-7 tanks). They also had two motorized infantry divisions and over 550 fighter and bomber planes. The Mongolians added two cavalry divisions.

In comparison, the Japanese Kwantung Army had only the 23rd Infantry Division. Its headquarters was far from the fighting. Japanese intelligence knew Zhukov was building up his forces but didn't react quickly enough. So, when the Soviets attacked, the Japanese commander Komatsubara was surprised.

To test the Japanese defenses, the Soviets launched three smaller attacks in early August. All three were pushed back, and the Soviets lost many soldiers and tanks. The Japanese also counterattacked and took some hilly ground. Even though there was no major fighting until August 20, Japanese casualties kept rising.

Zhukov decided it was time to break the stalemate. At 5:45 AM on August 20, 1939, Soviet artillery and 557 aircraft attacked Japanese positions. This was the first time the Soviet Air Force used fighter-bombers in such a big attack. About 50,000 Soviet and Mongolian soldiers attacked the east bank of the Khalkhin Gol.

Three infantry divisions and a tank brigade crossed the river, supported by many cannons and the Soviet Air Force. Once the Japanese were held in place by the central Soviet attack, Soviet armored units swept around their sides. They attacked the Japanese from behind, completely surrounding them. When the Soviet forces met at Nomonhan village on August 25, they trapped the Japanese 23rd Infantry Division.

On August 26, a Japanese counterattack to help the trapped division failed. On August 27, the 23rd Division tried to break out but couldn't. When the surrounded Japanese soldiers refused to surrender, they were hit again with artillery and air attacks. By August 31, Japanese forces on the Mongolian side of the border were destroyed. The Soviets had achieved their goal.

The Soviet Union and Japan agreed to stop fighting on September 15. The ceasefire began the next day at 1:10 PM.

What Happened Next

Japanese records show 8,440 killed and 8,766 wounded. They also lost 162 aircraft and 42 tanks. About 500 to 600 Japanese and Manchus were captured. Because Japanese military rules did not allow surrender, most of these captured men were listed as killed. Some sources suggest much higher Japanese casualties, but these are likely incorrect. The Kwantung Army's own records show 8,629 killed and 9,087 injured.

Recent information from Soviet records shows that Soviet losses were 9,703 killed or missing and 15,251 wounded. They also lost many vehicles, including 253 tanks, 250 aircraft, and 133 armored cars. Most Soviet tank losses were due to anti-tank guns.

Mongolian casualties were between 556 and 990 soldiers. They also lost 11 armored cars and many horses and camels.

Khalkhin Gol was one of the first times air power was used on a large scale to achieve a military goal. The two sides remained at peace until August 1945. That's when the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Japanese territories after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Air Combat Details

Soviet Aircraft Losses

| I-16 fighter | I-15 biplane fighter | I-153 biplane fighter | SB high-speed bomber | TB-3 heavy bomber | R-5 reconnaissance aircraft | Total: | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combat losses | 87 | 60 | 16 | 44 | 0 | 1 | 208 |

| Non-Combat losses | 22 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 42 |

| Total losses | 109 | 65 | 22 | 52 | 1 | 1 | 250 |

| Ref | |||||||

Japanese Aircraft Losses

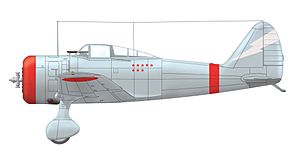

| Ki-4 reconnaissance aircraft | Ki-10 biplane fighter | Ki-15 reconnaissance | Ki-21 high speed bomber | Ki-27 fighter | Ki-30 light bomber | Ki-36 utility aircraft | Fiat BR.20 medium bomber | Transport aircraft | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerial combat losses | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 62 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 88 |

| Write-offs due to combat damage | 14 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 34 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 74 |

| Total combat losses | 15 | 1 | 13 | 6 | 96 | 18 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 162 |

| Combat damage | 7 | 4 | 23 | 1 | 124 | 33 | 6 | 20 | 2 | 220 |

| Ref | ||||||||||

Aircraft Ammunition Used

- USSR:

- Bomber flights: 2,015

- Fighter flights: 18,509

- Machine gun rounds fired: 1,065,323

- Cannon rounds used: 57,979

- Bombs dropped: 78,360 (totaling 1,200 tons)

- Japan:

- Fighter/bomber flights: 10,000 (estimated)

- Machine gun rounds fired: 1.6 million

- Bombs dropped: 970 tons

Impact of the Battle

Even though this battle isn't well-known everywhere, it was very important for Japan's actions in World War II. The Japanese Kwantung Army's defeat upset officials in Tokyo. This was not just because they lost, but because the army started and grew the conflict without permission from the Japanese government.

This defeat, along with strong resistance from China in the Second Sino-Japanese War, and a peace agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union, changed Japan's plans. The Japanese military leaders in Tokyo moved away from the idea of attacking the Soviet Union to take its resources in Siberia.

Instead, they started to support the idea of attacking Southeast Asia. This region had rich resources like oil and minerals, especially the Dutch East Indies. Masanobu Tsuji, a Japanese colonel who helped start the Nomonhan incident, later strongly supported the attack on Pearl Harbor. He wrote that his experience with Soviet firepower at Nomonhan convinced him not to attack the Soviet Union in 1941.

Because the United States and Britain stopped selling oil to Japan, Japan's war efforts were threatened. The only thing stopping Japan from taking the oil-rich Dutch East Indies was the US Pacific Fleet. This led Japan to focus its attention south, which resulted in the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Japan never launched a major attack against the Soviet Union. In 1941, Japan and the Soviet Union even signed agreements to respect each other's borders and stay neutral.

At the end of World War II, the Soviet Union broke its neutrality agreement and invaded Japanese territories in Manchuria, northern Korea, and Sakhalin island.

Soviet Learnings

The battle was the first big victory for Georgy Zhukov, who would become a very famous Soviet general. He earned his first "Hero of the Soviet Union" award. The other two generals, Grigori Shtern and Yakov Smushkevich, also played important roles and received the same award. However, they were later executed in 1941. Zhukov was promoted and moved to a different area.

Zhukov used the experience he gained at Khalkhin Gol in later battles. For example, in December 1941, he used similar tactics at the Battle of Moscow. He was able to launch the first successful Soviet counterattack against the German invasion. A Soviet spy in Tokyo, Richard Sorge, helped by telling the Soviet government that Japan was looking south and probably wouldn't attack Siberia. This allowed the Soviets to move many divisions from Siberia to defend Moscow.

A year after defending Moscow, Zhukov planned and carried out the Red Army's attack at the Battle of Stalingrad. He used a similar strategy: holding the enemy in the middle, secretly building up a large force behind them, and then attacking from the sides to trap the German army.

Despite their victory, the Soviets were not completely happy with their army's performance. They had a big advantage in technology, numbers, and firepower but still suffered many losses. Some blamed this on poor leadership.

Even though their victory and the peace agreement with Japan secured the Far East, the Red Army remained careful. They kept a large force in the Far East throughout World War II, even when the war in Europe was at its worst.

Japanese Learnings and Changes

The Japanese also learned from the battle. They realized they needed to improve their military equipment. As a result, tank production increased. They also created a new anti-tank gun, the Type 1 47 mm anti-tank gun, to counter Soviet weapons. This new gun was put on Type 97 Chi-Ha tanks, creating a better tank model.

General Tomoyuki Yamashita was sent to Germany to learn about tank tactics. He returned stressing the need for more mechanized forces and medium tanks. Plans were made to create 10 new armored divisions.

However, Japanese industry could not produce enough weapons to keep up with the United States or the Soviet Union. Yamashita warned against going to war with them for this reason. But his advice was not fully followed, and Japanese military leaders eventually pushed for war with the United States. Despite their recent experience and improvements, the Japanese often underestimated their enemies. They focused on the bravery of individual soldiers to make up for fewer numbers and less industrial power.

The battles also showed a big problem with first aid. Japanese rules did not allow soldiers to give first aid without an officer's order, and training was poor. This meant many Japanese soldiers died from bleeding from untreated wounds. Also, many soldiers got sick with dysentery. The Japanese believed this was caused by Soviet biological weapons. To prevent diseases, future Japanese divisions included special departments for preventing epidemics and purifying water. Finally, Japanese food rations were found to be poor in quality and nutrition.

Remembering the Battle

After World War II, at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, some Japanese leaders were charged with starting a war against Mongolia and the Soviet Union. Some were found guilty.

Commemoration

The anniversary of the battle was first celebrated in 1969, 30 years after it happened. After its 50th anniversary in 1989, it became less important. But recently, it has become a significant event in Mongolian history again.

The Mongolian town of Choibalsan, where the battle took place, has a "G. K. Zhukov Museum." It is dedicated to Zhukov and the 1939 battle. Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, also has a "G. K. Zhukov Museum" with information about the battle. This museum opened on August 19, 1979.

For the 70th, 75th, and 80th anniversaries of the battle, the President of Russia has joined the celebrations. He often attends with the President of Mongolia and veterans from both countries.

On the 80th anniversary in 2019, a military parade was held in Choibalsan. It included soldiers from the Russian Armed Forces and the Mongolian Armed Forces. These troops had participated in joint military exercises the month before. Parades were also held in Russian regions near Mongolia. A concert also took place in Ulaanbaatar, featuring Russian and Mongolian singers.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Jaljin Gol para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Jaljin Gol para niños

- Mukden Incident

- Tientsin incident

- Kantokuen

- Mongolia in World War II

Images for kids

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |