Turco-Egyptian Sudan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Turco-Egyptian Sudan

السودان التركي-المصري (Arabic)

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1820–1885 | |||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

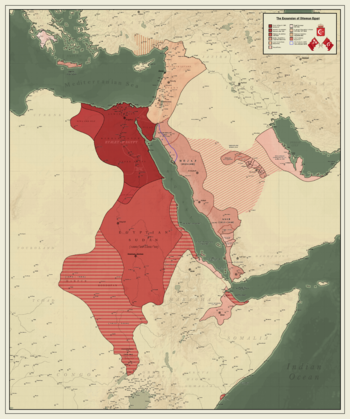

Map of Egypt with the Egyptian Sudan in the south

|

|||||||||||||

| Status | Administrative division of Eyalet of Egypt, Ottoman Empire (1820–1867) Administrative division of Khedivate of Egypt, Ottoman Empire (1867–1885) |

||||||||||||

| Capital | Khartoum | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, English | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||

|

• 1820–1848 (first)

|

Muhammad Ali Pasha | ||||||||||||

|

• 1879–1885 (last)

|

Tewfik Pasha | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

|

• Conquest of Sudan

|

1820 | ||||||||||||

| 1885 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | Egyptian pound | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Turco-Egyptian Sudan (Arabic: التركى المصرى السودان), also called Turkiyya (Arabic: التركية, at-Turkiyyah), was a time when Egypt ruled over what is now Sudan and South Sudan. This period lasted from 1820 to 1885. It began when Muhammad Ali Pasha, the ruler of Egypt, started to conquer Sudan. It ended when the city of Khartoum fell to Muhammad Ahmad, a religious leader who called himself the Mahdi.

Contents

Why Egypt Conquered Sudan

The Mamluks and Muhammad Ali's Plan

After Muhammad Ali took control in Egypt, some of his enemies, the Mamluks, ran away. They went south and set up a base in a place called Dunqulah in 1811. From there, they continued their slave trading.

In 1820, the Sultan of Sennar, Badi VII, told Muhammad Ali he couldn't make the Mamluks leave. So, Muhammad Ali sent 4,000 soldiers to invade Sudan. His goals were to get rid of the Mamluks and add Sudan to Egypt.

The Conquest Begins

Egyptian forces quickly defeated the Mamluks in Dunqulah. They also took control of Kurdufan and received Sennar's surrender. However, some local Arab tribes, like the Ja'alin tribes, fought back strongly against the invasion. This marked the start of Egyptian rule in Sudan.

Understanding 'Turkiyya' Rule

What 'Turkiyya' Means

'At-Turkiyyah' (Arabic: التركية) was the common name Sudanese people used for the time when Egypt and later Britain ruled Sudan. This period started with the conquest in 1820 and ended when the Mahdist movement took over in the 1880s. The word means both 'Turkish rule' and 'the time of Turkish rule'. It referred to being governed by people who were seen as Turkish-speaking leaders or those they appointed.

Who Were the Rulers?

The top leaders in the army and government were usually Turkish-speaking Egyptians. But the group also included people from Albania, Greece, and other parts of the Middle East. These people held important jobs within the Egyptian government led by Muhammad Ali and his family. Even Europeans like Emin Pasha and Charles George Gordon were part of this rule. They worked for the Egyptian rulers, known as Khedives.

The Ottoman Connection

The Egyptian Khedives were technically under the Ottoman Empire. This meant that everything they did was officially in the name of the Ottoman Sultan in Constantinople. This is why it was called 'Turkish' rule. Even though the Khedives were supposed to speak Turkish, Arabic quickly became the main language in government. Later, a term al-turkiyyah alth-thaniya (Arabic: التركية الثانية) was used for the later Anglo-Egyptian rule (1899–1956).

Life Under Egyptian Rule

Early Challenges and Changes

When the new government started in 1821, Egyptian soldiers often took food and supplies from the local people. They also charged very high taxes. Many ancient Meroitic pyramids were destroyed as soldiers searched for hidden gold. The slave trade also grew, causing many people in the fertile Al Jazirah region to run away.

Within a year, 30,000 Sudanese people were forced into the army and sent to Egypt for training. Many of them died from sickness and the new climate. The few who survived could only serve in army bases within Sudan.

Making Rule More Stable

As Egyptian control became stronger, the government became a bit less harsh. Egypt created a large government system in Sudan and expected the country to pay for itself. Farmers and herders slowly returned to Al Jazirah. Muhammad Ali also gained the support of some tribal and religious leaders by not making them pay taxes.

Egyptian soldiers and Sudanese conscripts, along with hired fighters, were stationed in cities like Khartoum, Kassala, and Al Ubayyid. They also guarded smaller outposts.

Local Administration and Growth

The Shaiqiyah people, who had fought against the Egyptians, were defeated. They were then allowed to work for the Egyptian rulers as tax collectors and horsemen under their own leaders, called shaykhs. The Egyptians divided Sudan into provinces, which were then split into smaller areas. These smaller areas usually matched the territories of different tribes.

In 1823, Khartoum became the main city for Egyptian rule in Sudan. It quickly grew into a big market town. By 1834, it had 15,000 people and was where the Egyptian deputy lived. In 1835, Khartoum became the home of the Hakimadar (governor general). Many army towns also grew into important centers for their regions. Local shaykhs and tribal leaders took on administrative jobs.

Legal and Religious Changes

In the 1850s, Egypt changed the legal system in both Egypt and Sudan. They introduced new laws for business and crimes, which were handled in regular courts. This reduced the importance of qadis (Islamic judges), whose religious courts only dealt with personal matters. Many Sudanese Muslims did not trust these courts. This was because the courts followed the Hanafi school of law, which was different from the stricter Maliki school traditional in Sudan.

The Egyptians also built mosques and set up religious schools and courts. Teachers and judges for these places were trained at Cairo's Al Azhar University. The government supported the Khatmiyyah, a religious group whose leaders encouraged working with the government. However, many Sudanese Muslims thought this official religion was not true to their beliefs.

Economy and Slave Trade

Until it was slowly stopped in the 1860s, the slave trade was the most profitable business in Sudan. It was a major reason for Egypt's interest in the country. The government encouraged economic growth through state-controlled businesses that exported slaves, ivory, and gum arabic. In some areas, tribal land, which used to be shared, became the private property of the sheikhs. Sometimes, this land was even sold to people outside the tribe.

Renewed Egyptian Interest

The rulers who came after Muhammad Ali, Abbas I (1849–54) and Said (1854–63), did not pay much attention to Sudan. But the rule of Ismail I (1863–79) brought new interest in the country. In 1865, the Ottoman Empire gave Egypt control of the Red Sea coast and its ports. Two years later, the Ottoman Sultan officially recognized Ismail as Khedive of Egypt and Sudan. This was a title Muhammad Ali had used before without official permission.

Egypt organized and placed soldiers in new regions like Upper Nile, Bahr al Ghazal, and Equatoria. In 1874, they conquered and added Darfur. Ismail appointed Europeans to lead these regions and gave more important government jobs to Sudanese people. With pressure from Britain, Ismail also worked to stop the slave trade in northern Sudan. He also tried to create a new army like European armies, which would not rely on slaves for soldiers.

Problems with Modernization

These changes caused problems. Army units rebelled, and many Sudanese people did not like soldiers living among them. They also disliked being forced to work on public projects. Efforts to stop the slave trade made city merchants and the Baqqara Arabs angry. These groups had become rich by selling slaves.

Developing Sudan Under Egyptian Rule

Khartoum's Growth

Khartoum, which started as a military camp, grew into a town with over 500 brick houses. This happened under the first Egyptian Governor-General, Khurshid Pasha.

Taxes and Refugees

New taxes were very harsh, and people were afraid of violent punishment. Because of this, many farmers along the Nile left their land and fled to the hills. Later leaders, like Ali Khurshid Pasha, were more understanding. Khurshid Bey offered forgiveness to refugees who returned from the border with Ethiopia. He also made all shaykhs and religious leaders completely free from taxes.

Searching for Gold

Even though they didn't find much gold at first, the Egyptians kept looking for it in Sudan. There was new interest in the Fazogli region in the 1830s. Muhammad Ali even sent European experts there and visited the area himself. Only a small amount of gold was ever found. In the end, Fazogli became an Egyptian penal colony (a place where prisoners were sent), not a mining center.

Sudanese Soldiers and the Slave Trade

Recruiting Soldiers

In the 1830s, Muhammad Ali focused his army on other areas. So, 'Ali Kurshid Pasha, the Governor General of Sudan, had to get more local slave soldiers. He often led raids into the Blue Nile region and the Nuba Mountains. He also went down the White Nile, attacking the Dinka and Shilluk territories to capture slaves for Khartoum.

Slave raiding was difficult and not always profitable. For example, in 1830, an attack on the Shilluk people involved 2,000 soldiers but only captured 200 slaves. In 1831–1832, an expedition of 6,000 soldiers attacked Jabal Taka in the Nuba Mountains. This attack failed, and Khurshid lost 1,500 men.

New Ways to Get Slaves

Rustum Bey, a governor under Khurshid, had more success with slave expeditions in the west. In January 1830, he captured 1,400 people and sent 1,000 young men to Egypt. In 1832, another expedition captured 1,500 people for the army.

Ahmed Pasha, Khurshid's successor, found a cheaper way to get slaves. Instead of raiding, he made a new tax. Each person who paid taxes had to buy and hand over one or more slaves. Governor-General Mūsā Pasha Ḥamdī (1862–1865) combined these methods. He required local leaders to provide a certain number of slaves. He also personally led raids if there weren't enough.

Under Khedive Abbas I (1848–1854), each local leader had to provide a specific number of men as part of their yearly taxes. In 1859, his successor Muhammad Sa'id (1854–1863) ordered a personal bodyguard of black soldiers. Slaves continued to be taken for Sudanese regiments and this bodyguard, even after the slave trade was officially banned.

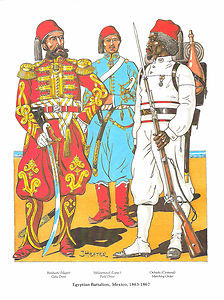

The Army's Makeup

By 1852, the Egyptian army in Sudan had 18,000 soldiers. By 1865, it grew to over 27,000. Most of these soldiers were either slaves or people who volunteered from Sudan. The officers were usually 'Turks' (meaning Turkish-speaking, from different backgrounds) and Egyptians. Later, some trusted Sudanese soldiers were promoted to higher ranks.

Sometimes, Sudanese slave troops fought outside Sudan. In 1835, they were sent to Arabia. In 1863, French Emperor Napoleon III asked for a Sudanese regiment to fight in Mexico. These soldiers were excellent fighters and handled the climate better than Europeans. One special case was Michele Amatore, a Sudanese slave who joined the Italian army in 1848.

Expanding Egyptian Territory

Advancing South and West

The Egyptians slowly expanded their control. They moved south along the White Nile and reached Fashoda in 1828. In the west, they reached the borders of Darfur. The Red Sea ports of Suakin and Massawa also came under their control. In 1838, Muhammad Ali himself visited Sudan. He sent special groups to look for gold along the White and Blue Nile rivers. In 1840, the regions of Kassala and Taka were added to Egyptian lands.

Battles and Borders

In 1831, Khurshid Pasha led 6,000 soldiers east to attack the Hadendoa people. They crossed the Atbarah River, but the Hadendoa tricked the Egyptians into an ambush in a forest. The Egyptians lost all their cavalry and 1,500 soldiers. Despite this, the town of Gallabat surrendered to Khurshid in 1832.

In 1837, Egyptian tax collectors killed an Ethiopian priest in Sudan. This led to a large Ethiopian army of about 20,000 soldiers coming into the Sudanese plains. The Egyptian army at al-Atish, east of El-Gadarif, was reinforced. However, their commander was a civilian with no military experience. The Ethiopians easily won before leaving.

Images for kids

See also

- List of governors of pre-independence Sudan

- History of Sudan

Sources

- "Country Studies".. Federal Research Division.

– Sudan

- Beška, Emanuel, Muhammad Ali´s Conquest of Sudan (1820-1824). Asian and African Studies, 2019, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 30–56. url=https://www.academia.edu/39235604/MUHAMMAD_ALI_S_CONQUEST_OF_SUDAN_1820_1824_

- Dr. Mohamed H. Fadlalla, Short History of Sudan, iUniverse, 30 April 2004, ISBN: 0-595-31425-2

- Dr. Mohamed Hassan Fadlalla, The Problem of Dar Fur, iUniverse, Inc. (21 July 2005), ISBN: 978-0-595-36502-9

- Egyptian Royalty by Ahmed S. Kamel, Hassan Kamel Kelisli-Morali, Georges Soliman and Magda Malek.

- L'Egypte D'Antan... Egypt in Bygone Days by Max Karkegi.