History of Tibet (1950–present) facts for kids

The history of Tibet from 1950 to today tells the story of big changes in Tibet. Before 1950, Tibet was mostly independent. In 1950, China invaded Tibet, leading to the Battle of Chamdo. In 1951, Tibetan leaders signed an agreement with China called the Seventeen Point Agreement. This agreement said that Tibet was part of China, but it also promised that Tibet would have its own government led by the 14th Dalai Lama, who is Tibet's spiritual and political leader.

However, things changed. In 1959, there was an uprising in Tibet. The Dalai Lama had to escape to India to stay safe. There, he started the Central Tibetan Administration, which is like a government-in-exile. He also said that the Seventeen Point Agreement was no longer valid because it was signed under pressure. In 1965, most of Tibet became the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) within China.

Contents

Tibet in the Early 1950s

In 1949, as the Communists took control of China, Tibet's government asked all Chinese officials to leave. Before 1951, Tibet acted like its own country. But both the old Chinese government and the new Communist government claimed Tibet as part of China.

The new Chinese Communist government, led by Mao Zedong, quickly showed its power in Tibet. On October 7, 1950, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) invaded the Tibetan area of Chamdo. The Tibetan forces were much smaller and surrendered by October 19, 1950.

In 1951, Tibetan leaders met with the Chinese government in Beijing. They signed the Seventeen Point Agreement. This agreement made Tibet part of China. Some Tibetan leaders did not agree with it, saying it was signed under pressure. But the Tibetan National Assembly accepted it. The Dalai Lama later said the agreement was forced on Tibet.

According to the agreement, the area under the Dalai Lama's rule was supposed to be very independent. In western Tibet, Chinese Communists did not immediately change the traditional way of life. From 1951 to 1959, Tibetan society, with its lords and estates, continued as before. The Dalai Lama's government kept many symbols of its independence. In 1954, a census counted about 2.77 million Tibetans in China. China also built highways to Lhasa, connecting it to India, Nepal, and Pakistan.

However, in Tibetan areas of Qinghai, known as Kham, which were outside the Dalai Lama's government, things were different. Land was taken from noblemen and monasteries and given to serfs. This was called land reform.

Unrest and Uprising: 1956-1958

By 1956, there was unrest in eastern Kham and Amdo, where land reform had been fully put into practice. Rebellions started and spread to other parts of Tibet. In some areas, Chinese Communists tried to set up farming communities, like they were doing across China.

A rebellion against Chinese rule began in Amdo and eastern Kham in June 1956. This uprising, which got some help from the American CIA, eventually reached Lhasa. The Tibetan resistance movement grew. Many Tibetans were killed during these conflicts.

The Chinese government also affected religious beliefs. Those who practiced Buddhism, including the Dalai Lama, faced difficulties. The Chinese government tried to control religion and felt threatened by the Dalai Lama. Many Tibetans and the Dalai Lama found safety in India, where they could practice Buddhism peacefully.

In 1959, China's land reforms and military actions against rebels led to the 1959 Tibetan uprising. In Lhasa, many Tibetans were killed in just a few days. The resistance spread. Fearing the Dalai Lama would be captured, unarmed Tibetans surrounded his home. With help from the CIA, the Dalai Lama fled to India. On March 28, the Chinese government put the Panchen Lama in charge in Lhasa. They said he was the rightful leader since the Dalai Lama was gone. In 2009, March 28 became "Serfs Emancipation Day" in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Chinese authorities say that on this day in 1959, one million Tibetans were freed from serfdom.

After this, some resistance fighters operated from Nepal. Operations continued from the Kingdom of Mustang with about 2,000 rebels. Many were trained in the United States. Guerrilla fighting continued for several years. In 1969, American support was stopped, and the Nepalese government ended the operation.

Major Changes: 1959-1976

The 1959 Uprising

Armed conflict between Tibetan rebels and the Chinese army began in 1956. This was in the Kham and Amdo regions, where socialist reforms had been made. The fighting later spread to other parts of Tibet.

In March 1959, a major revolt happened in Lhasa. This city had been under Chinese control since the Seventeen Point Agreement in 1951. On March 12, protesters in Lhasa declared Tibet's independence. Within days, Tibetan troops helped the Dalai Lama escape into exile during the uprising. Artillery shells landed near the Dalai Lama's Palace, leading to the full force of the uprising. The fighting lasted only about two days. Tibetan rebel forces were greatly outnumbered and poorly armed. Many Tibetans lost their lives during this uprising and the fighting that followed.

Famine in China

China faced a widespread famine between 1959 and 1961. This was caused by drought, bad weather, and the policies of the Great Leap Forward. Many people died during this time. Tibet was one of the areas most affected by this famine.

Human Rights Report

In 1951, the Seventeen Point Agreement included promises from China. These promises were to keep Tibet's political system, protect the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama, allow religious freedom, and not force reforms. However, a group of international lawyers, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), found that China had broken these promises. They said Tibet's government had the right to reject the agreement, which it did in 1959.

In 1960, the ICJ released a report to the United Nations. This report accused China of genocide in Tibet. It said that Tibetans were not allowed to take part in their own cultural life, which the Chinese were trying to destroy.

During the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards caused a lot of damage. They destroyed many cultural sites across China, including Buddhist sites in Tibet. Only a few important monasteries were left without major damage.

Tibet Autonomous Region

In 1965, the area that had been under the Dalai Lama's government (Ü-Tsang and western Kham) was renamed the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). This region was supposed to be autonomous, meaning it had some self-rule. The head of government was a Tibetan. However, this Tibetan leader was always under the control of the Chinese Communist Party's First Secretary, who was not Tibetan. The role of Tibetans in high positions in the TAR Communist Party was very small.

The Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, which started in 1966, was a terrible time for Tibet, as it was for the rest of China. Many Tibetans died violent deaths. The number of intact monasteries in Tibet dropped from thousands to less than ten. This made Tibetans even more resentful towards the Chinese. Some Tibetans took part in the destruction, but it's unclear if they truly believed in the Communist ideas or if they participated out of fear.

New Approaches and International Focus: 1976-1987

After Mao Zedong died in 1976, Deng Xiaoping tried to improve relations with Tibetan leaders living in exile. He hoped they would return to China. Chinese officials thought Tibetans in Tibet were happy under Chinese rule. But when Tibetan leaders from exile visited Tibet in 1979-1980, Chinese officials were surprised. Thousands of Tibetans cried and showed great respect to the visitors.

These events led Chinese Party Secretary Hu Yaobang and Vice Premier Wan Li to visit Tibet. They were upset by what they saw. Hu announced a plan to improve life for Tibetans. This plan aimed to boost their economy and allow more freedom for Tibetan culture, religion, and language. It also called for more universities and colleges in Tibet and more Tibetans in local government.

New meetings between Chinese and exiled Tibetan leaders happened from 1981 to 1984, but no agreements were reached.

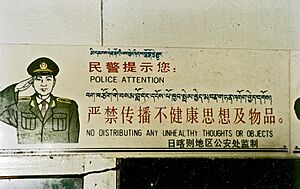

In 1986-1987, the Tibetan government-in-exile tried to get more international support for human rights in Tibet. In response, the United States House of Representatives supported Tibetan human rights in June 1987. Between September 1987 and March 1989, four big protests against Chinese rule happened in Lhasa. These riots showed how much Tibetans resented the situation. In 1987, the Panchen Lama said that about 5% of the population in Qinghai had died in prisons. The United States passed a law in 1988-1989 supporting Tibetan human rights. These riots, however, led to stricter Chinese policies in Tibet. Martial law was even put in place in 1989. More non-Tibetans moved to Lhasa, and the economy there became more controlled by Han Chinese. Lhasa became a city where non-Tibetans were as many as or more than Tibetans.

Recent History: 1988-Present

Hu Jintao became the Party Chief of the Tibet Autonomous Region in 1988. In 1989, the 10th Panchen Lama died. Many Tibetans believe Hu was involved in his death. A few months later, protests in Lhasa led to the deaths of 450 Tibetans that year. The 1990 census found 4.59 million ethnic Tibetans in China. The Chinese government says the Tibetan population has doubled since 1951.

In 1995, the Dalai Lama chose 6-year-old Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as the 11th Panchen Lama. But the Chinese government chose another child, Gyaincain Norbu. The Dalai Lama's choice, Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, and his family are missing. Amnesty International says they were kidnapped. Beijing says they are living secretly for protection.

Economic Growth

In 2000, the Chinese government started its Western Development Strategy. This plan aimed to help the economies of its poorer western regions. It included large projects like the Qinghai-Tibet Railway. However, some worry these projects help military movement and Han Chinese migration. Robert Barnett reported that 66% of official jobs in Tibet are held by Han Chinese. There are still fewer Tibetans in high government and legal jobs in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

The Chinese government says its rule has brought economic development to Tibetans. They say the Western Development Strategy helps western China, including Tibet, become more prosperous. They also claim that the Tibetan government did little to improve lives before 1950.

The Chinese government says that from 1951 to 2007, the Tibetan population in Lhasa-controlled Tibet grew from 1.2 million to almost 3 million. The GDP of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) is now thirty times what it was before 1950. Workers in Tibet have some of the highest wages in China. The TAR now has 22,500 km of highways, compared to none in 1950. All modern education in the TAR started after the revolution. The TAR now has 25 scientific research institutes. Infant mortality has dropped a lot, and life expectancy has risen from 35.5 years in 1950 to 67 in 2000.

The government also points to the publishing of the traditional Epic of King Gesar, which was mostly told orally before. They also highlight that 300 million Renminbi have been spent since the 1980s to protect Tibetan monasteries. The Chinese government sees the Cultural Revolution as a disaster for all of China. They view the Western Development plan as a helpful effort to bring prosperity to western China, including Tibet.

In 2008, the Chinese government started a project to preserve 22 historical and cultural sites in Tibet. This included important monasteries.

Tibetan Language

Most ethnic Tibetans, about 92-94%, speak Tibetan. In primary schools, teaching is almost entirely in Tibetan. But from secondary school onwards, teaching is in both Tibetan and Chinese.

Tibetologist Elliot Sperling has noted that China does try to support Tibetan culture. There are three Tibetan-language television channels in China's Tibetan areas. The Tibet Autonomous Region has a 24-hour Tibetan-language TV channel. There are also channels for speakers of Amdo Tibetan and Khams Tibetan.

In October 2010, Tibetan students protested. This was after the Chinese government said that Mandarin Chinese would be used in lessons and textbooks by 2015, except for Tibetan language and English classes.

2008 Unrest

Protests in March 2008 turned into riots in Lhasa. Tibetan crowds attacked Han and Hui people. The Chinese government responded quickly, setting curfews and asking journalists to leave. Many international leaders expressed concern. Some people protested in cities in Europe and North America.

After the 2008 unrest, Tibetan areas of China were closed to journalists for a time. Major monasteries were also locked down. Chinese authorities said over 1,000 people who were detained had been released. However, Tibetan groups in exile claimed that hundreds were still held in early 2009. Tibetan members of the Chinese Communist Party were told to remove their children from Tibetan exile community schools.

Who Lives in Tibet?

The number of Han Chinese people in Tibet is a sensitive topic and is debated. The Government of Tibet in Exile, China, and the Tibetan independence movement have different views.

Some Tibetan towns and villages are in India and Nepal. For example, the city of Leh in India has many ethnic Tibetans. There are also several Tibetan villages in northern Nepal. These areas are not currently claimed by Tibetan Exile Groups.

The Government of Tibet in Exile disagrees with many of China's population numbers. They say China's numbers do not include Chinese soldiers in Tibet or unregistered migrants. They believe China is trying to make Tibet more like China and reduce the chances of Tibetan independence.

Population Numbers (2000 Census)

| Main ethnic groups in Greater Tibet by region, 2000 census. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Tibetans | Han Chinese | Others | ||||

| Tibet Autonomous Region: | 2,616,329 | 2,427,168 | 92.8% | 158,570 | 6.1% | 30,591 | 1.2% |

| – Lhasa PLC | 474,499 | 387,124 | 81.6% | 80,584 | 17.0% | 6,791 | 1.4% |

| – Qamdo Prefecture | 586,152 | 563,831 | 96.2% | 19,673 | 3.4% | 2,648 | 0.5% |

| – Shannan Prefecture | 318,106 | 305,709 | 96.1% | 10,968 | 3.4% | 1,429 | 0.4% |

| – Xigazê Prefecture | 634,962 | 618,270 | 97.4% | 12,500 | 2.0% | 4,192 | 0.7% |

| – Nagqu Prefecture | 366,710 | 357,673 | 97.5% | 7,510 | 2.0% | 1,527 | 0.4% |

| – Ngari Prefecture | 77,253 | 73,111 | 94.6% | 3,543 | 4.6% | 599 | 0.8% |

| – Nyingchi Prefecture | 158,647 | 121,450 | 76.6% | 23,792 | 15.0% | 13,405 | 8.4% |

| Qinghai Province: | 4,822,963 | 1,086,592 | 22.5% | 2,606,050 | 54.0% | 1,130,321 | 23.4% |

| – Xining PLC | 1,849,713 | 96,091 | 5.2% | 1,375,013 | 74.3% | 378,609 | 20.5% |

| – Haidong Prefecture | 1,391,565 | 128,025 | 9.2% | 783,893 | 56.3% | 479,647 | 34.5% |

| – Haibei AP | 258,922 | 62,520 | 24.1% | 94,841 | 36.6% | 101,561 | 39.2% |

| – Huangnan AP | 214,642 | 142,360 | 66.3% | 16,194 | 7.5% | 56,088 | 26.1% |

| – Hainan AP | 375,426 | 235,663 | 62.8% | 105,337 | 28.1% | 34,426 | 9.2% |

| – Golog AP | 137,940 | 126,395 | 91.6% | 9,096 | 6.6% | 2,449 | 1.8% |

| – Gyêgu AP | 262,661 | 255,167 | 97.1% | 5,970 | 2.3% | 1,524 | 0.6% |

| – Haixi AP | 332,094 | 40,371 | 12.2% | 215,706 | 65.0% | 76,017 | 22.9% |

| Tibetan areas in Sichuan province | |||||||

| – Ngawa AP | 847,468 | 455,238 | 53.7% | 209,270 | 24.7% | 182,960 | 21.6% |

| – Garzê AP | 897,239 | 703,168 | 78.4% | 163,648 | 18.2% | 30,423 | 3.4% |

| – Muli AC | 124,462 | 60,679 | 48.8% | 27,199 | 21.9% | 36,584 | 29.4% |

| Tibetan areas in Yunnan province | |||||||

| – Dêqên AP | 353,518 | 117,099 | 33.1% | 57,928 | 16.4% | 178,491 | 50.5% |

| Tibetan areas in Gansu province | |||||||

| – Gannan AP | 640,106 | 329,278 | 51.4% | 267,260 | 41.8% | 43,568 | 6.8% |

| – Tianzhu AC | 221,347 | 66,125 | 29.9% | 139,190 | 62.9% | 16,032 | 7.2% |

| Total for Greater Tibet: | |||||||

| With Xining and Haidong | 10,523,432 | 5,245,347 | 49.8% | 3,629,115 | 34.5% | 1,648,970 | 15.7% |

| Without Xining and Haidong | 7,282,154 | 5,021,231 | 69.0% | 1,470,209 | 20.2% | 790,714 | 10.9% |

This table includes all Tibetan self-governing areas in China, plus Xining and Haidong. These two are included to complete the numbers for Qinghai province. They are also claimed as parts of Greater Tibet by the Government of Tibet in exile.

P = Prefecture; AP = Autonomous prefecture; PLC = Prefecture-level city; AC = Autonomous county. These numbers do not include Chinese soldiers on active duty. The number of Han Chinese settlers in cities has grown since then. But a study from 2005 showed only a small increase in Han population in the TAR from 2000 to 2005. There was little change in eastern Tibet.

See also

- Tibet (1912–1951)

- Tibet under Qing rule

- Tibetan diaspora

- Tibetan Resistance Since 1950

- Tibetan sovereignty debate

- Tibetan Buddhism

- Annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China

- Sinicization of Tibet

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |