History of wildfire suppression in the United States facts for kids

Wildfire suppression in the United States is all about how people have tried to control and stop wildland fires over many years. For most of the 1900s, any fire, big or small, was put out as fast as possible. This was because people were scared of huge, destructive fires like the Peshtigo Fire in 1871 and the Great Fire of 1910. But in the 1960s, scientists learned that fire is actually a natural and important part of many ecosystems, helping new plants grow. So, today, instead of trying to stop every fire, experts sometimes let natural fires burn or use controlled burns as a tool to keep forests healthy.

Contents

How Indigenous People Used Fire

For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples of the Americas have used fire as a tool to manage their lands. These burning practices were a key part of their way of life, helping them care for wildlife habitats and gather food. They would set small, controlled fires to clear out dead plants and brush. This stopped bigger, more dangerous fires from starting. These small fires also helped certain plants grow and made it easier to hunt animals like bison and elk.

However, when settlers came to America, they brought new rules. In California, for example, fire suppression was made law as early as 1850. By 1911, with the Weeks Act, many traditional Indigenous burning practices became illegal. This meant less burning happened, and more and more plants built up on the forest floor. Experts now believe that over a century of stopping all fires has led to the huge, intense wildfires we see today.

Stopping these traditional fires also hurt Indigenous communities. It meant less food and changed their social structures. Many scholars call this "Colonial Ecological Violence." Now, the U.S. Forest Service and scientists are realizing how important these traditional burning methods are. Indigenous peoples are helping them understand how fire is needed for healthy forests and communities.

Early Firefighting Efforts

In the eastern United States, where there's a lot of rain, wildfires are usually small. But as people moved west into drier areas, they faced much larger and more destructive fires. These included huge range fires on the Great Plains and forest fires in the Rocky Mountains.

Yellowstone National Park was created in 1872. By 1886, the U. S. Army was put in charge of protecting it. The Army saw many fires burning. They decided to focus on stopping fires caused by humans near roads, as they didn't have enough soldiers to fight every fire. This was one of the first times federal land managers decided to let some fires burn while controlling others. This policy of stopping fires was also used in Sequoia, General Grant, and Yosemite when they became national parks in 1890.

Some terrible fires in history greatly influenced how fire was managed. The worst wildfire disaster in U.S. history happened in 1871. The Peshtigo Fire in Wisconsin killed over 1,500 people. The Santiago Canyon Fire of 1889 in California and especially the Great Fire of 1910 in Montana and Idaho also made people believe that all fires were dangerous and needed to be stopped. The Great Fire of 1910 burned about 3 million acres (12,000 km²) and killed 86 people. This event pushed government agencies, like the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service, to focus on stopping all wildfires. This led to the 1911 Weeks Act, which helped fund fire prevention.

Stopping All Fires: The Rule

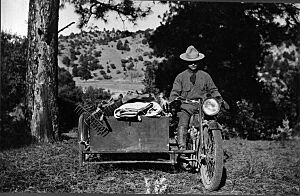

Before the mid-1900s, most forest managers thought all fires should be put out. By 1935, the U.S. Forest Service had a rule: all wildfires had to be put out by 10 AM the morning after they were first seen. Firefighting teams were set up across public lands, often with young men working during fire season. By 1940, special firefighters called smokejumpers would parachute from planes to put out fires in faraway places.

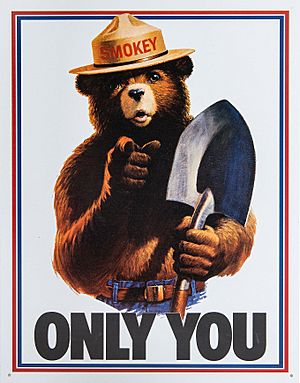

During World War II, there was a great need for wood, so fires that destroyed timber were seen as very bad. In 1944, the U.S. Forest Service started an ad campaign to teach people that all fires were harmful. They used a cartoon black bear named Smokey Bear. Smokey Bear is still famous today with his saying, "Only you can prevent wildfires." Early Smokey Bear ads sometimes made people think most western wildfires were caused by humans. But in places like Yellowstone, lightning causes many more fires than humans do.

Stopping all fires was the main goal, even though it was hard to do until new vehicles, equipment, and roads (like Fire trails) became common in the 1940s. Some people, like environmentalist Aldo Leopold in 1924, argued that wildfires were good for ecosystems. They said fires helped clear out dead plants and allowed new ones to grow. Over the next 40 years, more and more foresters and scientists agreed that wildfires were beneficial. But the policy of putting out all fires by 10 AM continued, which led to a lot of fuel (dead plants and trees) building up in some forests.

Changing Fire Policies

The policy of stopping all fires started to be questioned in the 1960s. People noticed that no new giant sequoia trees were growing in California's forests. This was a problem because these huge trees actually need fire to help their seeds sprout and grow.

In 1962, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall asked a group of experts to study wildlife management in national parks. This group wrote the Leopold Report, which said that parks should be managed as whole ecosystems, including natural processes like fire. Then, the 1964 Wilderness Act encouraged allowing natural processes to happen.

Because of these changes, the National Park Service changed its policy in 1968. They started to see fire as an important part of nature. Fires were allowed to burn if they stayed within certain areas and helped meet park goals. The Forest Service made similar changes in 1974, allowing lightning-caused fires to burn in wilderness areas. This included both natural fires and fires set on purpose, called prescribed fires. By 1978, the Forest Service dropped the 10 AM rule.

However, some big fires in the 1980s, like the Yellowstone fires of 1988, led to a review of these new policies. Even though the Yellowstone fires were not caused by controlled burns, the review found that allowing fires to burn naturally was still a good idea, but the plans needed to be stronger. After this, programs that allowed "wildland fire use" slowly started to grow again.

Wildfire Management Today

In 1994, the South Canyon Fire caused a lot of discussion after 14 firefighters died. This led to a big review of federal wildfire policy. The report said that the most important thing was the safety of firefighters and the public. It also said that wildland fire should be used to protect and improve natural resources, and allowed to act in its natural role as much as possible. By the end of the 1990s, "wildland fire use" programs were strong and growing.

These new fire management methods have shown good results. For example, in 2000, the Hash Rock fire in Oregon burned into an area that had been managed with wildland fire use in 1996. When the wildfire reached that area, it actually went out! This shows how letting some fires burn can help prevent bigger, more dangerous ones later.

Today, there's a growing interest in bringing back traditional Indigenous burning practices. Jackie Fielder, an Indigenous organizer, suggested creating an Indigenous wildfire task force in California. This idea is based on the work of the Karuk Tribe, who are leaders in using cultural burning to reduce wildfire risk and help important plants grow. Experts like Bill Tripp from the Karuk Tribe believe that more education about Indigenous practices can offer better ways to manage wildfires. This approach could not only reduce fire threats but also create jobs and give Indigenous people more say in land management.

See also

- Smokejumpers

- Hotshot Crew

- Helitack

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |