Hope Diamond facts for kids

The Hope Diamond in the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

|

|

| Weight | 45.52 carats (9.104 g; 0.3211 oz) |

|---|---|

| Color | Fancy Dark Greyish Blue (GTA) |

| Cut | Antique cushion |

| Country of origin | India |

| Mine of origin | Kollur Mine |

| Discovered | Unknown |

| Cut by | Unknown |

| Original owner | Jean-Baptiste Tavernier |

| Owner | Smithsonian Institution |

| Estimated value | US0–350 million |

The Hope Diamond is a famous 45.52 carats (9.104 g; 0.3211 oz) blue diamond. It was found in the 1600s in the Kollur Mine in Guntur, India. The diamond gets its beautiful blue color from tiny amounts of boron inside it. Its large size has helped scientists learn more about how diamonds form deep inside the Earth.

This special stone is one of the Golconda diamonds. The first records show that a French gem merchant, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, bought it in 1666. Back then, it was called the Tavernier Blue. The stone was later cut and renamed the French Blue (Le bleu de France). Tavernier sold it to King Louis XIV of France in 1668.

The diamond was stolen in 1792 during a time of big changes in France. It was then recut, and the largest part of it appeared in 1839. This is when it got the name Hope Diamond, from the Hope banking family who owned it.

Over the years, the Hope Diamond has had many owners. One famous owner was Evalyn Walsh McLean, a well-known person in Washington. She often wore the diamond. In 1949, a New York gem merchant named Harry Winston bought the diamond. He showed it around for several years. In 1958, he gave it to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in the United States. You can see it there today, on display all the time.

About the Hope Diamond

The Hope Diamond is also known by other names. These include Le Bijou du Roi ("the King's Jewel"), Le bleu de France ("the French Blue"), and the Tavernier Blue. It is a large, 45.52-carat (9.104 g; 0.3211 oz), deep-blue diamond. It is set in a special necklace called a pendant Toison d’or.

Today, the diamond is kept in the National Gem and Mineral collection. This collection is at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C..

The diamond looks dark greyish-blue in normal light. This is because of tiny bits of boron in its structure. But if you shine ultraviolet light on it, it glows red! This red glow is called phosphorescence. The Hope Diamond is a special kind of diamond known as a type IIb diamond.

The Hope Diamond has traveled a long way. It went from Hyderabad, India, to France, then Great Britain, and finally to the United States. It is often called the "most famous diamond in the world."

What the Hope Diamond is Like

Weight and Size

In 1988, experts measured the Hope Diamond. They found it weighs 45.52 carats (9.104 g; 0.3211 oz). People have compared its size and shape to a pigeon egg or a walnut. It is shaped like a pear. The diamond measures about 25.60 mm long, 21.78 mm wide, and 12.00 mm deep. That's about 1 inch by 7/8 inch by 15/32 inch.

Color and Glow

The Hope Diamond is described as a "fancy dark greyish-blue." Some say it has a "steely-blue" color. In 1996, the Gemological Institute of America called it fancy deep grayish blue. When you look at it, the gray color is so dark that it makes the diamond look almost blackish-blue. This is especially true in regular light.

The diamond has a very strong red phosphorescence. This means it glows red after being exposed to ultraviolet light. This glow lasts for a while after the light is turned off. Some people thought this strange quality made the diamond seem "cursed." Scientists use this red glow to tell real blue diamonds from fake ones. The glow happens because of a mix of boron and nitrogen in the stone.

Clarity and Cut

The diamond's clarity is rated as VS1. This means it has very few tiny flaws. It also has some whitish lines, which are common in blue diamonds. The way the diamond is cut is called "cushion antique brilliant." This cut has many flat surfaces, or facets.

What it's Made Of

In 2010, scientists took the diamond out of its setting. They wanted to study its chemical makeup. They found boron, hydrogen, and possibly nitrogen. The amount of boron changes from place to place in the diamond. It is the boron that gives the stone its blue color.

Hardness

Diamonds, including the Hope Diamond, are the hardest natural minerals on Earth. But diamonds can still break if they are not handled carefully. This is because of weak spots in their crystal structure. Diamond cutters use these weak spots to split rough diamonds into smaller, perfect pieces. Then, they shape and polish the stone. Only another diamond can scratch a diamond. So, special tools with diamond particles are used to grind and polish the facets. This makes the gem sparkle by bending and reflecting light in many ways.

The Diamond's Journey Through History

How it Began

The Hope Diamond formed deep inside the Earth about 1.1 billion years ago. Like all diamonds, it was made when carbon atoms joined together very strongly. The Hope Diamond was originally found in a type of rock called kimberlite. It was then taken out and shaped into the beautiful gem we see today. The tiny bits of boron in its carbon structure give it its rare blue color.

From India to France

Records from the French gem merchant, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, show that he got the gem in India in 1666. It likely came from the Kollur mine in the Guntur area of Andhra Pradesh. This was part of the Golconda kingdom back then.

Many details about the diamond's early history are not clear. We don't know exactly where it was found, or who owned it first. Tavernier brought a large, uncut stone to Paris. This stone was the first version of what would become the Hope Diamond. It was known as the Tavernier Blue. It was a roughly cut, triangular stone weighing about 115 carats (23.0 g; 0.81 oz).

Tavernier's book, Six Voyages, shows sketches of large diamonds he sold to King Louis XIV. A blue diamond is shown among them. Tavernier mentioned the Kollur Mine as a source of colored diamonds. One report says he sold this large blue diamond and about a thousand other diamonds to King Louis XIV in 1669. The price was 220,000 livres, which was like 147 kilograms of pure gold.

The French Blue

In 1678, King Louis XIV asked his jeweler, Jean Pitau, to recut the Tavernier Blue. This resulted in a 67.125-carat (13.4250 g; 0.47355 oz) stone. Royal records then called it the Blue Diamond of the Crown of France. English historians later called it the French Blue. The king had the stone set on a cravat-pin.

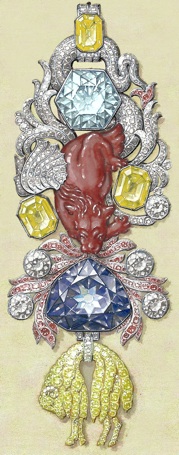

Louis XV, Louis XIV's great-grandson, had the French Blue set into a more fancy pendant in 1749. This was for the Order of the Golden Fleece. The piece included a red spinel shaped like a dragon. It also had many red and yellow diamonds.

After Louis XV died, the diamond became the property of his grandson, Louis XVI. His wife, Queen Marie Antoinette, used many of the French Crown Jewels. But the French Blue stayed in this pendant.

Stolen and Hidden

On September 11, 1792, during the French Revolution, thieves broke into the Royal Storehouse. They stole most of the Crown Jewels over five days. Many jewels were found later, but the French Blue was not among them. It disappeared from history.

Louis XVI was executed in 1793, and Marie Antoinette later that year. People often linked these deaths to a "curse" on the diamond. However, Marie Antoinette never wore the Golden Fleece pendant. It was only for the King.

It is believed that the French Blue was quickly taken to London after being stolen. The exact stone known as the French Blue was never seen again. It was almost certainly recut during this time. The largest piece that remained became the Hope Diamond. Some say the recutting was "butchered." It cut off 23.5-carat (4.70 g; 0.166 oz) from the larger stone and hurt its sparkle.

In 2005, a three-dimensional model of the French Blue was found in Paris. This helped confirm that the Hope Diamond was indeed cut from the stolen French Blue. The model showed 20 unknown facets on the back of the French Blue. It also confirmed that the diamond was roughly recut. This changed its original shape and style.

Historians think one burglar, Cadet Guillot, took several jewels, including the French Blue, to London. There, the French Blue was cut into two pieces.

In the United Kingdom

In September 1812, a blue diamond like the Hope Diamond was recorded in London. It belonged to a diamond merchant named Daniel Eliason. This is the first time the Hope Diamond's history can be clearly traced. This date was just after 20 years had passed since the French Blue was stolen. This meant the time limit for the crime had ended.

For a long time, people wondered if this diamond in Britain was the same one that belonged to the French kings. In 2008, scientific tests confirmed that the Hope Diamond and the French Blue were the same gem.

There are different stories about what happened to the diamond during these years. Eliason's diamond might have been bought by George IV of the United Kingdom. But there are no clear records of this in the royal archives. After George IV died in 1830, his debts were huge. The diamond was likely sold to help pay them off. It did not stay with the British royal family.

Later, a rich London banker named Thomas Hope bought the stone. He paid either $65,000 or $90,000 for it. In 1839, the Hope Diamond was listed in a catalog of gems owned by his brother, Henry Philip Hope. The diamond was set in a simple necklace. It was surrounded by many smaller white diamonds. After the Hope family owned it, the stone became known as the "Hope Diamond."

Henry Philip Hope died in 1839. His nephews fought in court for ten years over his gems. The oldest nephew, Henry Thomas Hope, received the Hope Diamond. It was shown at big exhibitions in London in 1851 and Paris in 1855. But it was usually kept safe in a bank vault.

When Henry Thomas Hope died in 1862, his wife Anne Adele inherited the gem. She worried that her son-in-law might sell it. So, when Adele died in 1884, the Hope Diamond went to her grandson, Henry Francis Pelham-Clinton. He had to add "Hope" to his name when he became an adult.

Lord Francis Hope received his inheritance in 1887. But he could not sell the diamond without court permission. In 1894, Lord Francis Hope married the American singer May Yohé. She claimed she wore the Hope Diamond at parties. But her husband said she didn't. Lord Francis spent too much money and got into financial trouble. He had to sell the diamond.

In 1901, after a long legal fight, he got permission to sell the Hope Diamond to pay his debts. He sold it for £29,000 to Adolph Weil, a London jewel merchant. Weil then sold it to Simon Frankel, a diamond dealer in New York.

In the United States (1902–present)

The diamond's story from 1902 to 1907 is a bit unclear. Some say it stayed in a safe, only brought out for wealthy buyers. Others say it was bought and sold back to Frankel. There were even stories in The New York Times about bad luck happening to temporary owners. But it's more likely the diamond stayed with the Frankel jewelry firm. The firm faced money problems during the depression of 1907. They even called the gem the "hoodoo diamond."

In 1908, Frankel sold the diamond to Selim Habib, a rich Turkish diamond collector. The price was $400,000. But in 1909, the stone was sold again at an auction of Habib's belongings. The auction catalog said the Hope Diamond had never been owned by the Sultan. Another report, however, said Sultan Abdul Hamid did own it. He supposedly ordered Habib to sell it when his rule was in trouble.

The Parisian jewel merchant Simon Rosenau bought the Hope Diamond for 400,000 francs. He then sold it in 1910 to Pierre Cartier for 550,000 francs.

Pierre Cartier tried to sell the Hope Diamond to Evalyn Walsh McLean and her husband in 1910. Cartier was a great salesman. He told Mrs. McLean the diamond's famous history. He kept it hidden in special paper to build excitement. Mrs. McLean became impatient and asked to see it. She later said Cartier "held before our eyes the Hope Diamond."

She didn't buy it at first. So, Cartier had it reset in a new, modern style. Mrs. McLean liked it much more then. There were different stories in The New York Times about the sale. One said the McLeans wanted to back out because of the diamond's "misfortunes." But in 1911, the couple bought the gem for over $300,000. Some think the McLeans made up the "curse" concern to get more attention for their new jewel.

The diamond was placed on white silk. It was surrounded by many small, pear-shaped white diamonds. Mrs. McLean wore it to fancy parties. She would sometimes "misplace" it on purpose. She would even make a game out of "finding the Hope" for her guests. But the diamond was never actually stolen while they owned it.

When Mrs. McLean died in 1947, she left the diamond to her grandchildren. Her will said it had to stay with trustees until the oldest child was 25. This would have stopped any sale for 20 years. But the trustees got permission to sell her jewels to pay her debts. In 1949, they sold them to Harry Winston, a jeweler in New York. Winston bought McLean's "entire jewelry collection."

For the next ten years, Winston showed the diamond necklace in his "Court of Jewels" tour across the United States. It was also shown at events and charity balls. The diamond even appeared on a TV quiz show in 1955. Winston also had the diamond's bottom facet slightly recut to make it sparkle more.

At the Smithsonian

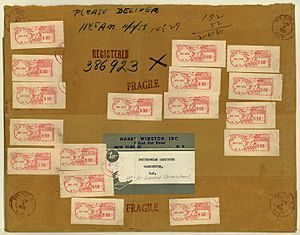

Smithsonian mineralogist George Switzer convinced Harry Winston to give the Hope Diamond to the museum. Winston agreed on November 10, 1958. He sent it through U.S. Mail in a brown paper-wrapped box. It was sent as simple registered mail and insured for $1 million. The postage cost $2.44, and the insurance was $145.29. When it arrived, it became Specimen #217868.

Harry Winston didn't believe in the curse stories. He gave the diamond hoping it would help the United States start a great gem collection. Winston died in 1978. His gift did help bring many more donations to the museum.

For its first 40 years at the National Museum of Natural History, the Hope Diamond was in a glass safe. It left only a few times. It went to an exhibition in Paris in 1962. It also visited Harry Winston's place in New York in 1984 and 1996.

To keep it safe during the 1962 trip to Paris, Switzer carried the Hope Diamond in a velvet pouch. His wife had sewn the pouch. He pinned it inside his pants pocket for the flight.

In 1997, the museum's gem gallery was updated. The necklace was moved to a rotating stand inside a cylinder of thick, bulletproof glass. It is in its own display room. The Hope Diamond is the most popular jewel on display and the main attraction.

In 1988, experts from the Gemological Institute of America studied it. They saw "evidence of wear" and its "remarkably strong phosphorescence." They also noted its clarity was "slightly affected by a whitish graining." This is common in blue diamonds.

In 2005, the Smithsonian confirmed that the Hope Diamond was cut from the stolen French Blue crown jewel. This was after a year of computer research.

In 2009, the Smithsonian announced a new, temporary setting for the jewel. This was to celebrate 50 years at the museum. It was shown as a stand-alone gem without a setting. It had been removed for cleaning before, but this was the first time it was shown by itself. Before, it was in a platinum setting. It had 16 white diamonds around it.

The Hope Diamond returned to its traditional setting in late 2010. On November 18, 2010, it was shown in a new necklace called "Embracing Hope." This was made by the Harry Winston firm. People voted on the design for the new setting.

A Smithsonian curator said the diamond is "priceless" because it is "irreplaceable." It is reported to be insured for $250 million. On January 13, 2012, the diamond was put back into its historic setting. The temporary necklace was then fitted with another diamond worth "at least a million dollars." This necklace will be sold to help the Smithsonian.

Changes Over Time

| Date acquired | Owner | Change in diamond | Value when sold | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1653 | Jean-Baptiste Tavernier | 112.5 Old French karats, 116 metric carats | 220,000–720,000 livres. Tavernier received a special title as part payment. | Acquired between 1640 and 1667, possibly 1653 |

| 1668 | Louis XIV of France | Triangular 69 metric-carat gem set on a cravat-pin in 1674. | Given as a gift | |

| 1715 | Louis XV of France | Made into a fancy pendant called Order of the Golden Fleece | Given as a gift | |

| 1775 | Louis XVI of France | 69 metric carats | Stolen | |

| 1791 | Government of France | Stolen | ||

| 1792 | Unknown | Stolen | ||

| 1812 | Daniel Eliason, a London jeweler | About 44 non-metric carats (44-carat (8.8 g; 0.31 oz)) | $65,000; $90,000 | |

| Between 1812 and 1830 | George IV of the United Kingdom | Sold to pay off the king's debts after he died | ||

| Sometime between 1830 and 1839 | Henry Phillip Hope (1774–1839) | Became known as the "Hope Diamond" | Given as a gift | |

| 1839 | Henry Thomas Hope | Given as a gift | Displayed at the 1851 London Exhibition | |

| 1861 | Henry Pelham-Clinton, Duke of Newcastle | Given as a gift | Hope gave his daughter the gem after she married. | |

| 1884 | Lord Francis Hope, 8th Duke of Newcastle | $250,000 | ||

| 1894 | May Yohé, Lady Henry Francis Hope | £29,000 | May Yohé was the wife of Lord Henry Francis Hope | |

| 1901 | Adolph Weil, London jewel merchant | $141,032 (about £28,206). | ||

| 1901 | Simon Frankel | |||

| 1908 | Selim Habib (Salomon? Habib) | Possibly as an agent for the Turkish Sultan Hamid | ||

| 1908 | Sultan Abdul Hamid II of Turkey | 44 3/8 carats (44.375-carat (8.8750 g; 0.31306 oz)) | 400,000 francs; second estimate: $80,000. | It is debated if the Sultan ever owned it |

| 1909 | Simon Rosenau | 550,000 francs | ||

| 1910 | Pierre Cartier | Reset to appeal to Evalyn McLean; became a pendant | $150K; $300K+; $185K | Different estimates for the sale price |

| 1911 | Edward Beale McLean and Evalyn Walsh McLean | Weight thought to be 44.5 carats (44.5-carat (8.90 g; 0.314 oz)) | $180,000 | The entire McLean collection was sold to Winston |

| 1947 | Harry Winston | The diamond's bottom facet was slightly recut to make it sparkle more | A New York City jeweler; he showed it around the US to make it popular | |

| 1958 | Smithsonian Institution | Settings, mountings, scientific study; weight found to be 45.52 metric carats in 1974 | $200–$250 million (if sold in 2011) | Insured for $250 million |

The "Curse" of the Hope Diamond

Stories and Publicity

The Hope Diamond has many stories about a "curse." People say it brings bad luck and sadness to anyone who owns or wears it. But many believe these stories were made up. They helped make the diamond more mysterious and famous. More publicity usually made the gem more valuable and newsworthy.

Some old stories said the Hope Diamond was stolen from the eye of a statue of the Hindu goddess Sita. But like the "curse of Tutankhamun" in Egypt, these legends were likely created by writers in the 1800s and early 1900s. They wanted to add mystery to the stone and help sell newspapers.

These stories made people think that anyone who had the diamond would have bad luck.

Owners and Their Fates

| Date acquired |

Owner | Fate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1653 | Jean-Baptiste Tavernier | Lived to be 84 years old. | Acquired between 1640 and 1667, possibly 1653 |

| 1668 | Louis XIV of France | Had a long and successful reign; lived to be 76. | |

| 1722 | Louis XV of France | Lived to be 64 years old. | |

| 1775 | Louis XVI of France | Executed in 1793, at age 38. | |

| 1775 | Marie Antoinette | Executed in 1793, at age 37. | Wife of Louis XVI |

| 1805? | King George IV of the United Kingdom | Lived to be 67 years old. | It's not certain if he ever owned it. |

| 1812 | Daniel Eliason, a London jeweler | Died in 1824, at age 71. | |

| 1830 | Thomas Hope | Lived to be 62 years old. | |

| 1839 | Henry Philip Hope | ||

| 1861 | Henry Pelham-Clinton, 6th Duke of Newcastle | Lived to be 45 years old. | |

| 1884 | Lord Francis Hope | Went bankrupt; had to sell the diamond; lived to be 75. | |

| 1894 | May Yohé | Singer, divorced, remarried several times, died without much money, at age 72. | Wife of Lord Francis Hope |

| 1901 | Adolph Weil, London jewel merchant | ||

| 1901 | Simon Frankel | ||

| 1908 | Selim Habib (Salomon? Habib) | Possibly as an agent for the Turkish Sultan Hamid | |

| 1908 | Sultan Abdul Hamid II of Turkey | Lost his power in 1909; died in 1918, at age 75. | It is debated if the Sultan ever owned it. |

| 1909 | Simon Rosenau | ||

| 1910 | Pierre Cartier | Lived to be 86 years old. | |

| 1911 | Edward Beale McLean and Evalyn Walsh McLean |

Divorced in 1932; Edward had mental illness and died at 51 or 52; Evalyn died at 60 from pneumonia in 1947. |

|

| 1947 | Harry Winston | Lived to be 83 years old. | Jeweler who gave it to the Smithsonian in 1958. |

| 1958 | Smithsonian Institution | Has grown and gained more visitors. |

Replicas and Reconstructions

In 2007, a lead model of the French Blue diamond was found. It was in the gem collections of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. This discovery led to a big study by researchers. Before this, they only had old drawings of the diamond. The 3D model allowed them to use computer-aided drawing to study it.

The methods for rebuilding the gem digitally are explained in the "Theft and Disappearance" section of this article. The famous Golden Fleece pendant of Louis XV was rebuilt around the French Blue. This included the "Côte de Bretagne" spinel and other diamonds.

As part of the study, the "Tavernier Blue" diamond was also rebuilt. This was done using the original French version of Tavernier's book. The Smithsonian Institution provided information about the Hope Diamond.

The lead model was likely made around 1815. It came with a label saying the French Blue was owned by "Mr. Hope of London." This helped researchers figure out what might have happened to the diamond after it was stolen in 1792.

These findings helped experts understand the diamond's missing years. They believe Henry Phillip Hope might have owned the French Blue after the 1792 robbery. He might have gotten it around 1794–1795. At that time, one of the thieves, Cadet Guillot, also arrived in London.

The diamond's owners might have felt they needed to recut it quickly. This would hide its identity. If the French government found out, they might have tried to get it back. By 1824, the diamond was back with Mr. Hope.

The lead model was very important. It gave enough information for the French museum to make the first exact copies of both the Tavernier and French Blue diamonds. They used a material called cubic zirconia, which looks like diamonds. These copies are now displayed with the French Crown Jewels.

Artisans also recreated the fancy Golden Fleece of King Louis XV of France. This was a very detailed piece of jewelry. The original was stolen and broken in 1792. The rebuilt jewel includes copies of the French Blue and other diamonds. It took three years of careful work to recreate this jewel. It shows the amazing skill of both today's and 1700s jewelers.

New discoveries also helped make more copies possible. A drawing of the Golden Fleece was found in Switzerland in the 1980s. Two blue diamonds that were on the original jewel were also found. These findings helped artisans create a copy that looks almost exactly like the amazing French Blue masterpiece.

The Golden Fleece emblem also had another large blue diamond, called "the Bazu." This diamond was cut in 1749. It was described as "light sky blue." This shows that the Golden Fleece had many different colored gems.

The emblem also had a third large gem, the Côte de Bretagne dragon. A copy of this dragon was made from wax. Its color was made to look like the original spinel.

More than 500 other diamond copies were cut from cubic zirconia. They were colored red for flames and yellow for the fleece. The copies were made to look like the original artwork. The metal parts were made of silver. This kept costs down but still looked good. Many different artists helped with this project.

All the stones were set using techniques from the 1700s. Finally, a fancy box was made for the Golden Fleece. It was covered in red leather and decorated with King Louis XV's royal symbol. A dark red ribbon holds the jewel inside the box.

-

Lead cast of the "French Blue" diamond, discovered in 2007 at the National Museum of Natural History (France) by Farges (about 31 mm × 26 mm (1.2 in × 1.0 in)).

-

Computer reconstruction of the "French Blue" diamond, as cut by Jean Pitau for King Louis XIV of France in 1673 (about 31 mm × 25 mm (1.22 in × 0.98 in)).

-

The recreated great Golden Fleece of King Louis XV of France, presented by H. Horovitz (left) and François Farges (right) in Paris, on June 30, 2010.

See also

- Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom

- List of diamonds

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |