Iwane Matsui facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Iwane Matsui

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | July 27, 1878 Nagoya, Aichi, Japan |

| Died | December 23, 1948 (aged 70) Sugamo Prison, Tokyo, Occupied Japan |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1897–1938 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 6th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Division |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | Russo-Japanese War

Siberian Intervention Second Sino-Japanese War

|

| Awards | Order of the Golden Kite First Class, Order of the Rising Sun First Class Order of the Sacred Treasure First Class Victory Medal Military Medal of Honor |

| Spouse(s) |

Fumiko Isobe

(m. 1912) |

| Other work | President of the Greater Asia Association |

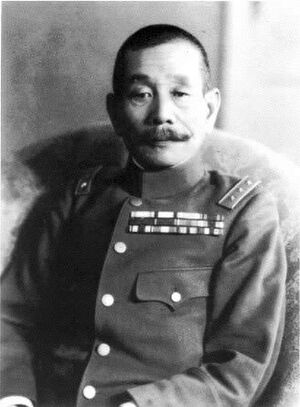

Iwane Matsui (松井 石根, Matsui Iwane, July 27, 1878 – December 23, 1948) was a high-ranking general in the Imperial Japanese Army. He led Japanese forces in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. He was later found responsible for serious wrongdoings during the war and died in 1948.

Matsui was born in Nagoya, Japan. He chose a military career and fought in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). After graduating from the Army War College in 1906, he became known as a leading expert on China. He strongly believed in pan-Asianism, an idea that Asian countries should unite. He helped start an important group called the Greater Asia Association.

Matsui retired from the army in 1935. However, he was called back in August 1937 when the Second Sino-Japanese War began. He led the Japanese forces in the Battle of Shanghai. After winning this battle, Matsui convinced Japan's military leaders to attack Nanjing, the capital city of China. The soldiers under his command captured Nanjing on December 13, 1937. During this time, many terrible events happened, known as the Nanjing Massacre.

Matsui retired from the army again in 1938. After Japan lost World War II, he was put on trial for war crimes. This trial was called the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE). He was found responsible for events in Nanjing and died in 1948. In 1978, he and other people found guilty at the trial were honored at Yasukuni Shrine. This act has caused some debate.

Contents

A Japanese General's Story

Early Life and Army Training

Iwane Matsui was born in Nagoya on July 27, 1878. He was the sixth son in his family. His father was a former samurai who had little money. Matsui wanted to help his family and chose a military career. Military schools in Japan at that time had the lowest tuition fees.

Matsui joined the Central Military Preparatory School in 1893. In 1896, he was accepted into the Imperial Japanese Army Academy. He was a very good student and graduated second in his class in 1897.

In 1901, Matsui entered the Army War College. This was a very selective school. In 1904, the college closed because the Russo-Japanese War started. Matsui was sent to Manchuria as a company commander. He was hurt in a battle, and many of his company were killed. After the war, Matsui finished his studies. He graduated at the top of his class in 1906.

Becoming a China Expert

Matsui was interested in Chinese culture his whole life. His father studied Chinese classics, and Matsui learned the Chinese language in military school. He admired Sei Arao, an army officer who believed China and Japan should work together. Arao thought they could resist Western influence if they formed a strong partnership. Matsui adopted this idea.

After graduating, Matsui asked to be stationed in China. This was unusual then, as China was not a popular posting. He wanted to be "a second Sei Arao." He worked in China from 1907 to 1911. He returned to Shanghai from 1915 to 1919. Later, he worked in China again from 1922 to 1924.

Because of his wide experience, Matsui became known as one of Japan's most important "China experts." He loved Chinese culture and enjoyed writing Chinese poetry. He traveled all over China and met many important Chinese leaders. He became good friends with Sun Yat-sen, who was the first president of the Republic of China.

Head of Intelligence

Matsui quickly moved up in rank. In 1923, he became a major general. From 1925 to 1928, he held an important job as Chief of the Intelligence Division of the Army General Staff. He was the first "China expert" to have this role. He greatly influenced Japan's policies toward China.

As Chief of Intelligence, Matsui supported Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang was trying to end the civil war in China and unite the country. Matsui hoped Chiang would succeed and work closely with Japan. This partnership would help resist Western influence and communism in Asia.

In 1928, the Japanese government sent troops to Jinan, China. This was to protect Japanese people and property. However, the troops clashed with the Chinese Army. Matsui went to Jinan to help solve the problem. While he was there, Japanese army officers killed Zhang Zuolin, a powerful leader in Manchuria. Matsui had supported Zhang. He went to Manchuria to find out what happened and demanded that the officers responsible be punished.

In December 1928, Matsui left his job. He took a year-long trip to Europe. He was interested in France and spoke French well.

Matsui's Vision for Asia

Relations between China and Japan worsened in September 1931. The Japanese Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria. Matsui was in Japan at the time. Later that year, he went to Geneva, Switzerland. He attended the World Disarmament Conference as a representative for the army.

At first, Matsui criticized the invasion. But he also felt that China and the League of Nations were unfairly blaming Japan. Matsui believed that Western powers were trying to cause conflict between Japan and China. He thought that the people of Manchuria were relieved by the Japanese takeover. He called it "the Empire's sympathy and good faith." He believed Asian nations should create their own "Asian League." This league would help China, just as Japan had helped Manchuria.

After returning to Japan in 1932, Matsui joined a group called the Pan-Asia Study Group. He convinced them to expand their small group into a large international movement. In March 1933, the group was renamed the Greater Asia Association. This group became very important in promoting pan-Asianism. Its goal was to unite, free, and make Asian peoples independent. Matsui used this group to promote his "Asian League" idea. His writings were widely read by Japan's leaders.

In August 1933, Matsui was sent to Taiwan to command the Taiwan Army. In October, he was promoted to general, the highest rank. While in Taiwan, he started a branch of the Greater Asia Association. He then returned to Japan in August 1934. He took a seat on Japan's Supreme War Council.

Meanwhile, relations with China continued to get worse. Matsui became less supportive of Chiang Kai-shek's government. He had strongly supported Chiang before. In 1933, Matsui criticized China's leaders. He said they had "sold out their own country" because they seemed to favor Western ideas. He began to agree with those in the army who wanted to use military force against Chiang Kai-shek.

Matsui's military career ended suddenly in August 1935. A general he supported was killed by a rival group. Matsui was tired of the conflicts within the Japanese Army. He decided to take responsibility for the scandal and retired from active duty.

A General in the Reserves

As a reservist, Matsui had more time for his pan-Asian project. From October to December 1935, he traveled through China. He spoke to Chinese politicians and business people about pan-Asianism. He also set up a new branch of the Greater Asia Association. In December 1935, he became President of the Greater Asia Association.

In early 1936, Matsui made another trip to China. This was a goodwill tour sponsored by the government. He met with Chiang Kai-shek. They did not agree on much, but they both opposed communism. Matsui thought this shared anti-communism could lead to cooperation. However, in December 1936, Chiang agreed to work with the Chinese Communist Party to resist Japan. Matsui saw this as a personal betrayal.

War in China: Shanghai and Nanjing

Leading the Shanghai Battle

In July 1937, a full-scale war broke out between Japan and China. This was the Second Sino-Japanese War. The fighting started in northern China and spread to Shanghai in August. The Japanese government decided to send more soldiers to Shanghai. These soldiers formed the Shanghai Expeditionary Army (SEA).

Because there were not enough active generals, Matsui was called back from retirement. On August 15, he was made commander of the SEA. His experience with China was a key reason for his selection. Some historians believe the army hoped Matsui could negotiate a peace with China after Shanghai was secured. Matsui said his goal was to make the Chinese people see Japanese troops as friends. He said he was going to "pacify his brother," not fight an enemy. However, a Chinese army friend of his said, "There can be no friendship between us while there is war."

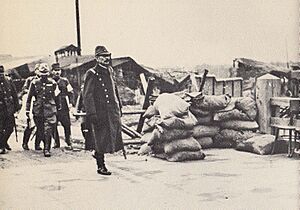

Matsui's troops landed near Shanghai on August 23. The initial landings went well, but the fighting on land became very intense. Many soldiers were hurt. Matsui felt he did not have enough soldiers and kept asking for more. He could not go ashore in Shanghai until September 10. On that day, he learned that three more divisions would join his command. Even with these new troops, it was hard to push back the Chinese.

Matsui mistakenly thought the Chinese Army would withdraw from Shanghai in October. He ordered strong attacks, expecting the campaign to end quickly. But the fighting continued. The turning point came on November 5. A new army, the 10th Army, landed south of Shanghai. This forced the Chinese Army to retreat quickly. Shanghai finally fell on November 26.

The fighting also affected Chinese civilians. Matsui showed concern for Chinese refugees. In October, he ordered improvements to refugee camps. He later gave a large personal donation to help set up a "safety zone" for Chinese civilians in Shanghai.

The Advance to Nanjing

On November 7, Matsui was made commander of the Central China Area Army (CCAA). This new position was created to lead both the SEA and the 10th Army. Matsui also continued to command the SEA until December 2. The army leaders wanted to keep the war contained. They set a "restriction line" to prevent the CCAA from leaving the Shanghai area.

However, Matsui had already told his superiors that he wanted to capture Nanjing. Nanjing was the capital city of China, about 300 kilometers west of Shanghai. Matsui strongly believed that the war would not end until Nanjing was taken. He thought that if Nanjing fell, Chiang Kai-shek's government would collapse. Matsui hoped to help form a new, democratic Chinese government that would benefit both Japan and China. Some historians also think Matsui wanted a big victory to end his military career.

On November 19, the 10th Army, led by Heisuke Yanagawa, crossed the restriction line. They began advancing on Nanjing. Matsui reportedly tried to stop Yanagawa. But he also told his superiors that marching on Nanjing was the right thing to do. On December 1, the army leaders finally approved an operation against Nanjing. By then, many Japanese units were already on their way.

Matsui had gotten his way, but he knew his troops were tired. He planned to advance slowly and take the city in two months. However, his officers did not follow his plan. They raced each other to be the first to Nanjing. Matsui changed his plans when he saw his armies were moving much faster than expected. Some say Matsui could not control his younger officers. They might have thought he was too old and would soon retire again. Matsui's command was also difficult because he was often sick with tuberculosis from December 5 to December 15. Even when ill, he continued to give orders from his bed.

On December 7, he moved his command post closer to the front lines. On December 9, he ordered a "summons to surrender" to be dropped over Nanjing. The Chinese Army did not respond. The next day, Matsui approved a full attack on the city. The CCAA had many casualties fighting north of the city. Matsui had forbidden using artillery there to protect two famous historical sites. The Chinese soldiers defending Nanjing soon gave up. Instead of formally surrendering, they threw away their uniforms and weapons and mixed with the city's people. The Japanese occupied Nanjing on the night of December 12/13. Japanese soldiers then committed many acts of violence, including killing prisoners and looting. These events are known as the Nanjing Massacre.

Events in Nanjing

Matsui and his officers wanted to make sure that property and people from other countries were not harmed. They knew their troops might not obey orders in Nanjing. To prevent this, Matsui added a long section called "Essentials for Assaulting Nanjing" to his orders on December 7. He told his divisions to send only one regiment into the city. This was to limit contact with Chinese civilians. He also reminded everyone that crimes like looting would be punished. However, his orders were not followed. Chinese soldiers had burned many buildings outside Nanjing. So, Matsui's officers decided they had to station all their men inside the city.

Matsui's orders did not say anything about how to treat Chinese prisoners of war (POWs). Matsui also made the situation worse when he insisted on entering Nanjing triumphantly on December 17. His officers in Nanjing objected. They were still trying to capture all the former Chinese soldiers hiding in the city. They had no place to hold them. Matsui held firm. In many cases, his men responded by executing their prisoners immediately after capture. Most of the large-scale killings in Nanjing happened just before Matsui's entry into the city.

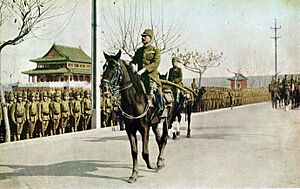

On December 16, Matsui rested at hot springs near Nanjing. The next day, he rode into Nanjing at the head of a large victory parade. It is not fully clear how much Matsui knew about the terrible events in Nanjing. His former Chief of Staff later said Matsui was told about "a few cases of plunder and outrage." Matsui's own diary also mentions being told about looting. He wrote, "The truth is that some such acts are unavoidable." A representative from the Japanese Foreign Ministry came to investigate. Matsui admitted some crimes had happened. He blamed his officers for letting too many soldiers into the city. After the war, Matsui's aide claimed Matsui stopped a plan to kill Chinese POWs. However, researchers have found many errors in this testimony.

Matsui left Nanjing on December 22 and returned to Shanghai. But reports of bad incidents in Nanjing continued to reach his headquarters. When Matsui returned to Nanjing on February 7, 1938, he gathered his officers. He scolded them for failing to prevent "a number of abominable incidents within the past 50 days."

Final Days in China

The capture of Nanjing did not make the Chinese government surrender. The war continued. Matsui began planning new military operations. He also worked on establishing a new Chinese government in Central China. He wanted to create a new government to rival Chiang Kai-shek's. The Reformed Government of the Republic of China was eventually formed in March 1938. However, Japan's army leaders were not very interested in his plan. They also kept refusing to approve his new military campaigns.

By then, there was a movement to remove Matsui from his post. Reports of the Nanjing events had reached the Japanese government. Some blamed Matsui for mishandling the situation and causing Japan international embarrassment. Some even wanted him tried for negligence. However, the Japanese government was not dismissing Matsui only because of Nanjing. The Foreign Ministry was unhappy with Matsui's anti-Western statements. The Army General Staff was also concerned about Matsui's conflicts with his officers. These conflicts were harming the chain of command.

On February 10, Matsui learned he would be relieved of command. He was replaced by another general. The army leaders changed many high-ranking officers in China. Matsui was one of eighty senior officers who were recalled at the same time.

Later Life and Trial

Retirement and Peace Efforts

Matsui left Shanghai on February 21, 1938, and arrived back in Japan on February 23. His return was kept secret, but reporters found out. He was greeted by cheering crowds. Later that year, Matsui bought a new home in Atami. He spent his winters there and his summers at his old house on Lake Yamanaka.

Even though he retired from the military, Matsui hoped to work with the Japanese-sponsored government in China. Instead, he accepted a job as a Cabinet Councillor, an advisory role, in June 1938. He served until January 1940. He resigned to protest the Prime Minister's opposition to an alliance with Nazi Germany.

In 1940, Matsui ordered the building of a statue of Kannon, the goddess of mercy. He had a special temple built in Atami for it. He named it the Koa Kannon, meaning "Pan-Asian Kannon." He dedicated it to all Japanese and Chinese soldiers who died in the war. The New York Times praised Matsui's act. It noted that "few Western generals have ever devoted their declining years to the memory of the men who died in their battles." For the rest of his life, Matsui prayed in front of the Koa Kannon every morning and evening while in Atami.

Matsui remained active in the pan-Asian movement. He served as President or Vice President of the Greater Asia Association throughout the war. After Japan entered World War II in December 1941, Matsui strongly argued that Japan should grant independence to the new territories it had taken. He wanted an alliance of Asian states to fight the Allied Powers. From June to August 1943, Matsui toured Asia to promote his ideas. He met with leaders in China, Singapore, and other countries. His efforts helped create the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. This was the peak of Matsui's lifelong dream of an "Asian League" against the West.

Matsui also served as President of the Association for the National Defense Concept. This group supported Japan's war efforts. In 1945, as the Allies advanced, Matsui declared that Japan would never leave the Philippines. He planned to speak against any surrender. However, on August 15, 1945, Matsui heard Emperor Hirohito announce that Japan had surrendered unconditionally.

The Allied occupation of Japan began soon after. On November 19, Matsui was ordered to be arrested for suspected war crimes. He was ill with pneumonia, so he was given time to recover. Before going to prison, Matsui asked his wife to adopt their maid. He also converted to Buddhism. On March 6, 1946, he surrendered to Sugamo Prison.

The Tokyo War Crimes Trial

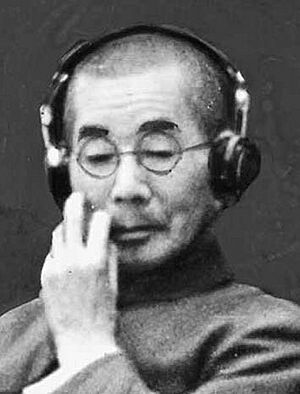

On April 29, 1946, Iwane Matsui was one of twenty-eight people formally charged at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE). This court was set up by the Allies to try Japanese war criminals. Prosecutors accused Matsui of planning aggressive war and of being responsible for the Nanjing Massacre.

Matsui had told friends he planned to defend himself and Japan's wartime actions. He insisted Japan acted to defend itself and to free Asia from Western control. About the war with China, Matsui called it "a fight between brothers within the 'Asian family.'" He said the war was fought "not because we hate them, but on the contrary because we love them too much."

Regarding the Nanjing Massacre, Matsui admitted he knew about a few crimes by individual soldiers. These included looting and murder. But he strongly denied that any large-scale killings had happened. Still, Matsui told the IMTFE he had "moral responsibility" for his men's wrongdoings. He denied "legal responsibility." He claimed the military police of each division were in charge of prosecuting crimes, not the army commander. However, Matsui also said he had urged that offenders be punished. The prosecution noted this implied he did have some legal responsibility.

The IMTFE dismissed most accusations against Matsui. He was found not guilty of thirty-seven of the thirty-eight charges. This included all charges related to planning aggressive wars.

However, he was found guilty and sentenced to death for his role in the Nanjing Massacre. The court said he "deliberately and recklessly disregarded their legal duty to take adequate steps to secure the observance and prevent breaches" of war laws. The IMTFE announced its decision on November 12, 1948. The court stated: "The Tribunal is satisfied that Matsui knew what was happening. He did nothing, or nothing effective to abate these horrors. He did issue orders before the capture of the city enjoining propriety of conduct upon his troops and later he issued further orders to the same purport. These orders were of no effect as is now known, and as he must have known... He was in command of the Army responsible for these happenings. He knew of them. He had the power, as he had the duty, to control his troops and to protect the unfortunate citizens of Nanking. He must be held criminally responsible for his failure to discharge this duty." This verdict set an early example for the idea of "command responsibility" in international law. This means a commander can be held responsible for crimes committed by their troops if they knew about them and did not act.

After hearing the verdict, Matsui spoke to his prison chaplain. He shared his feelings about the Nanjing events. He blamed the wrongdoings on a decline in the Japanese Army's morals since the Russo-Japanese War. He said, "The Nanjing Incident was a terrible disgrace... I assembled the higher officers and wept tears of anger before them... I told them that after all our efforts to enhance the Imperial prestige, everything had been lost in one moment through the brutalities of the soldiers. And can you imagine it, even after that, these officers laughed at me... I am really, therefore, quite happy that I, at least, should have ended this way, in the sense that it may serve to urge self-reflection on many more members of the military of that time."

On the night of December 22, 1948, Matsui met other prisoners who were also sentenced to death. As the oldest, Matsui led them in shouting three cheers for the Emperor. They were all executed shortly after midnight on December 23, 1948.

In 1978, all seven people executed by the IMTFE, including Iwane Matsui, were officially honored at Yasukuni Shrine. This was done in a secret ceremony. The public did not know about it until the next year.

Matsui's Legacy Today

In Japan, most historical writings about Iwane Matsui focus on his role in the Nanjing Massacre. Some people see him as a "tragic general" who was unfairly punished. Others believe he was directly responsible for the massacre.

Historian Yutaka Yoshida believes Matsui made six serious mistakes that led to the massacre. These include insisting on advancing without proper supplies, not protecting Chinese POWs, allowing too many soldiers into the city, and neglecting his duties as commander. Other historians also agree that Matsui bears responsibility for pushing the government to march on Nanjing.

However, some historians argue that his sentence was too harsh for simply failing to stop the massacre. Historian Tokushi Kasahara suggests that the trial did not fully investigate everyone involved. Instead, Matsui was made the main person responsible for the whole event.

Matsui has a somewhat negative reputation in China today. Some Chinese citizens have called him "the Hitler of Japan" because of his connection to the Nanjing Massacre. However, his name was not always known for this reason. In 1945, the Chinese Communist Party called Matsui a war criminal because of his propaganda work, not specifically for the Nanjing Massacre. Historian Masataka Matsuura notes that focusing only on Matsui's role in Nanjing distracts from his lifelong belief in pan-Asianism.

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |