John André facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John André

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 2 May 1751 London, Great Britain |

| Died | 2 October 1780 (aged 29) Tappan, New York, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Great Britain |

| Service/ |

British Army |

| Years of service | 1770–1780 |

| Rank | Major |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

| Signature | |

John André (born May 2, 1750 or 1751 – died October 2, 1780) was a British Army officer. He was a major and led the Secret Service for the British in America during the American Revolutionary War. He was caught and hanged as a spy by the American army. This happened because he helped Benedict Arnold try to give up the important fort at West Point, New York, to the British.

Many historians and even some American leaders like Alexander Hamilton thought of André as an honorable person. They did not agree with his punishment.

Contents

Who Was John André?

Early Life and Education

John André was born in London, Great Britain, on May 2, either in 1750 or 1751. His parents, Antoine André and Marie Louise Girardot, were wealthy Huguenots. His father was a merchant from Geneva, Switzerland, and his mother was from Paris.

John went to schools like St Paul's School and Westminster School in London, and also studied in Geneva. When he was 20, in 1771, he joined the British Army. He started as a second lieutenant and later became a full lieutenant.

His Military Career

Early in the American Revolutionary War, before America declared its independence, André was captured. This happened at Fort Saint-Jean in November 1775 by American General Richard Montgomery. He was held as a prisoner in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

He was allowed to move freely in the town because he promised not to escape. In December 1776, he was set free in a prisoner exchange. He was promoted to captain in 1777. He then became an aide to Major-General Grey. He served in battles like Brandywine and Germantown.

In 1778, André became an aide to Sir Henry Clinton, who was the top British commander in America. He was promoted to major.

A Popular Officer

John André was very popular in American cities like Philadelphia and New York when the British army occupied them. He was friendly and had many talents. He could draw, paint, create silhouettes, sing, and write poems.

He wrote many letters for General Henry Clinton. André also spoke four languages: English, French, German, and Italian. He even planned a big party called the Mischianza when General Howe left America.

While in Philadelphia, André stayed in Benjamin Franklin's house. It is believed he took some valuable items from there, including a painting of Franklin. This painting was later returned to the United States in 1906 and is now in the White House.

Secret Service Work

In 1779, André became the Adjutant General of the British Army in North America. This meant he was in charge of the army's administration. In April of that year, he also took over the British Secret Service in America.

The Benedict Arnold Plot

Around this time, Major André started talking with American General Benedict Arnold. Arnold was unhappy with the American side and wanted to switch to the British. Arnold's wife, Peggy Shippen, helped them communicate.

Arnold commanded the important fort at West Point. He agreed to give it to the British for a large sum of money.

On September 20, 1780, André traveled up the Hudson River on a British warship called the Vulture to meet Arnold. The next morning, American soldiers saw the warship. They started shooting at it, forcing it to move away.

Arnold sent a small boat to the Vulture to pick up André. André then met Arnold on shore. They talked in the woods until almost morning. After their meeting, André went with Arnold to the Joshua Hett Smith House (also known as the Treason House).

Because the British warship had to leave, André was stranded on shore.

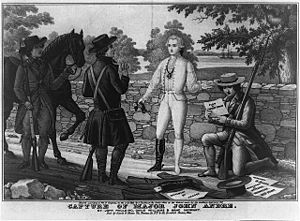

Captured!

To help André escape through American lines, Arnold gave him regular clothes and a special pass. André used the name John Anderson. He also carried six secret papers hidden in his stocking. These papers, written by Arnold, showed the British how to capture West Point.

André rode safely until September 23. Near Tarrytown, New York, three armed American militiamen stopped him. Their names were John Paulding, Isaac Van Wart, and David Williams.

André thought they were British supporters. He told them he was a British officer. But the men said they were American soldiers and that he was their prisoner. André then showed them his American pass, but their suspicions grew. They searched him and found Arnold's secret papers in his stocking.

André offered them his horse and watch to let him go, but they refused. Paulding realized André was a spy. They took him to the American army headquarters in Armonk, New York.

André was first held at Wright's Mill. Then he was taken across the Hudson River to Tappan, New York, where the American army headquarters were. There, he admitted who he really was.

At first, the American commander, Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson, decided to send André to Arnold. He did not suspect that Arnold, a hero, could be a traitor. But Major Benjamin Tallmadge, who led American Intelligence, arrived. He convinced Jameson to bring André back. Tallmadge had information that a high-ranking officer was planning to betray America, but he didn't know it was Arnold.

Jameson sent the secret papers found on André to General George Washington. But Jameson also sent a note to Arnold, telling him about the situation. This note gave Arnold time to escape to the British. Washington arrived at West Point later and was upset to see the fort's defenses were weak. He then received the full information from Tallmadge and tried to arrest Arnold, but it was too late.

Tallmadge later said that he and André talked while André was a prisoner. André asked how Washington would treat him. Tallmadge told him about Nathan Hale, an American spy hanged by the British. Tallmadge told André his fate would be similar.

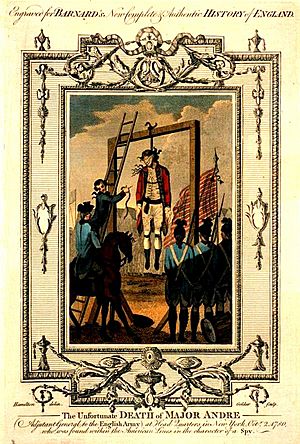

Trial and Execution

Washington called a group of senior officers to investigate. This group included important generals like Nathanael Greene and Lafayette.

André argued that he was just trying to get an enemy officer to switch sides, which he called "an advantage taken in war." He did not blame Arnold. André said he never meant to be behind American lines in civilian clothes. He also claimed that as a prisoner of war, he had the right to escape in civilian clothes.

On September 29, 1780, the officers decided André was guilty. They said he was behind American lines "under a fake name and in a disguise." They ruled that he should be seen as a spy and, according to the laws of war, he should be put to death.

Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander, tried everything to save André. André was his favorite aide. But Clinton refused to trade Arnold for André, even though he disliked Arnold. John André was hanged as a spy in Tappan, New York, on October 2, 1780.

A religious poem was found in his pocket after his death. He had written it two days before.

While he was a prisoner, André made American officers like him. They were sad about his death, just like the British. Alexander Hamilton wrote that André was a good man who suffered a fair punishment, but perhaps didn't deserve it. The day before he was hanged, André drew a picture of himself. Witnesses said André put the rope around his own neck.

Aftermath

The day André was captured, his poem "The Cow Chase" was published in New York. The poem was about a British mission that failed.

The man who hanged André, Nathan Strickland, was set free for doing the job. Joshua Hett Smith, who helped André, was tried but found not guilty because there wasn't enough proof.

The British government gave a pension to André's mother and three sisters after his death. His brother, William André, was made a baronet in his honor in 1781. In 1821, André's remains were moved from America to England. They were buried in Westminster Abbey, a very famous church, among kings and poets. A marble monument was placed there to remember him. In 1879, a monument was put up at the place where he was executed in Tappan.

The three men who captured André were John Paulding, David Williams, and Isaac Van Wert. The United States Congress gave each of them a silver medal and a yearly pension. In 1853, a monument was built to honor them where they captured André. Today, it is in Patriot's Park in Tarrytown, New York.

- "He was more unfortunate than criminal." – George Washington, October 10, 1780

- "An accomplished man and gallant officer." – George Washington, October 13, 1780

|

See also

In Spanish: John André para niños

In Spanish: John André para niños

- Intelligence in the American Revolutionary War

- John Champe (soldier)

- Jane Tuers