John Greaves facts for kids

John Greaves (born in 1602 – died October 8, 1652) was an English mathematician, astronomer, and antiquarian. An antiquarian is someone who studies old things.

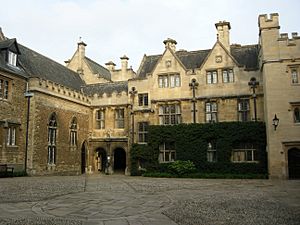

He went to Balliol College, Oxford and later became a Fellow at Merton College in 1624. John Greaves learned languages like Persian and Arabic. He also collected many old books and writings for Archbishop William Laud. Some of these books are still in the Merton College Library today.

From 1636 to 1640, he traveled through Italy and the Levant (countries in the eastern Mediterranean). During his travels, he carefully measured the Great Pyramid of Giza. He was a professor of geometry at Gresham College, London and astronomy at Oxford University. He collected special tools for measuring the stars, called astrolabes. These tools are now kept at the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford.

John Greaves was very interested in old weights and measures. He wrote about the Roman foot (a unit of length) and the denarius (a Roman coin). He was also a keen numismatist, meaning he loved studying coins. In 1645, he tried to change the Julian calendar, but his idea was not used. During the English Civil War, he supported King Charles I. However, he lost his jobs at Oxford in 1647 because of a conflict with Nathaniel Brent, who supported Parliament.

Contents

Who Was John Greaves?

His Early Life and Education

John Greaves was born in Colemore, a village near Alresford in Hampshire, England. He was the oldest son of John Greaves, who was a rector (a type of priest) in Colemore. His brothers were Nicholas Greaves, Thomas Greaves, and Sir Edward Greaves. Edward later became a doctor for King Charles II.

John Greaves started his education at his father's school. This school was for the sons of important families nearby. When he was 15, he went to Balliol College, Oxford from 1617 to 1621. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree there. In 1624, he became one of five new Fellows at Merton College. He earned his Master of Arts degree in 1628.

He began to study astronomy and languages from the Middle East. He especially focused on the works of ancient eastern astronomers. In 1630, Greaves was chosen to be the Gresham Professor of Geometry at Gresham College, London. He met Archbishop William Laud, who was a powerful leader at Oxford University. Laud wanted to publish English versions of Greek and Arabic books. Greaves' later travels helped him collect old writings for Laud.

Travels to Italy and Ancient Rome

In 1633, Greaves studied at the University of Leyden and became friends with Jacob Golius. Golius was a professor of Arabic. In 1635, Greaves went to the University of Padua in Italy. There, he met Johan Rode, an expert on ancient weights and measures.

After a short trip back to England, Greaves traveled to Europe again in 1636. He sailed to Rome and met other important scholars. He also met William Harvey, a famous doctor.

In Rome, he helped the Earl of Arundel try to buy an ancient Egyptian obelisk. This obelisk was broken into five pieces. Greaves measured the pieces and drew how the obelisk would look if it were fixed. However, the Pope at the time, Urban VIII, stopped the obelisk from being taken out of Italy. Later, another Pope, Innocent X, had it set up in the Piazza Navona. It is now part of Bernini's Fountain of the Four Rivers.

While in Rome, Greaves explored the Catacombs (underground burial places). He also drew pictures of the Pantheon and the Pyramid of Cestius. He studied ancient weights and measures very carefully. His work helped create the field of metrology, which is the science of measurement.

Exploring the Levant and Egypt

In 1637, John Greaves traveled to the Levant. One of his goals was to find the exact latitude of Alexandria. This was important because Ptolemy, a famous ancient astronomer, had made many observations there. Greaves sailed from England to Livorno, then visited Rome briefly. He arrived in Istanbul (Constantinople) around April 1638. There, he met the English ambassador, Sir Peter Wyche.

He bought many old writings in Istanbul. One was a copy of Ptolemy's Almagest, which he called "the fairest work I ever saw." Greaves ended up owning two copies of this important astronomy book. He had planned to visit the many libraries at Mount Athos. He wanted to list all their old books and writings. Mount Athos was usually only open to members of the Orthodox church. However, the leader of the church, Cyril Lucaris, gave Greaves special permission. Sadly, Lucaris was executed in June 1638, which stopped Greaves' trip.

Instead, Greaves went to Alexandria. There, he collected many Arabic, Persian, and Greek writings. He always took many notes in his notebooks and on blank pages of the books he bought. He also visited Cairo twice. He made a more accurate survey of the pyramids of Egypt than any traveler before him. He returned to England in 1640.

Trying to Change the Calendar

When John Bainbridge died in 1643, Greaves became the Savilian professor of astronomy at Oxford. He also became a senior reader for the Linacre lecture. However, he lost his Gresham professorship because he had not been doing his duties there.

In 1645, he tried to change the Julian calendar. His idea was to skip the extra day in February (February 29) for the next 40 years. The king approved his plan, but it was not put into action. This was because of the English Civil War. The Gregorian calendar, which we use today, was not adopted in Britain until 1752.

Losing His Job at Oxford

In 1642, Greaves was chosen as the subwarden of Merton College. Merton College was the only Oxford college to support Parliament during the English Civil War. This was due to an earlier disagreement between Nathaniel Brent, the Warden of Merton, and Greaves' supporter, William Laud. Brent had even testified against Laud in Laud's trial in 1644.

After Laud was executed in 1645, Greaves asked for Brent to be removed from his position. King Charles I removed Brent on January 27. However, in 1647, Parliament set up a group to investigate problems at Oxford University. Nathaniel Brent was the head of this group. After Thomas Fairfax captured Oxford for Parliament in 1648, Brent returned. Greaves was accused of taking college money and silver for King Charles.

Even though his brother Thomas spoke up for him, John Greaves lost his job at Merton and his astronomy professorship by November 9, 1648. Many of his books and writings disappeared after soldiers searched his rooms. Luckily, his friend John Selden managed to get some of them back. Greaves officially lost his professorship in August 1649.

Seth Ward took over as the Savilian Professor of Astronomy. Ward made sure Greaves was paid the money he was owed (about £500). Ward even gave some of his own salary to Greaves.

Later Life and Passing

John Greaves had enough money from his own family to live comfortably. He moved to London, got married, and spent his time writing and editing books. He died in London when he was 50 years old. He was buried in the church of St Benet Sherehog, which was later destroyed in the Great Fire of London.

His brother Nicholas Greaves was in charge of his will. John Greaves left his coin collection to Sir John Marsham. He gave his astronomy tools to the university for future astronomy professors to use. Two of his astrolabes, which his brother Nicholas had inscribed, are now in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford.

Greaves' Astronomy Tools

John Greaves had given his will to his friend Edward Pococke, who had traveled with him. His will originally said that his collection of astronomy tools, like astrolabes and quadrants, should go to Oxford University. But by 1649, Greaves was upset with the situation at Oxford after the civil war. He wrote to Pococke asking him to remove the gift of his instruments from the will. He felt there was no future for learning at Oxford. Pococke seemed to follow Greaves' wishes. After Greaves died in 1652, his brother Nicholas kept the collection.

However, when the Commonwealth ended in 1659, Nicholas Greaves decided to follow his brother's original wish. He gave the instruments to Oxford University for the Savilian Professors of Astronomy to use. They were kept in the professor's room at the top of the Eastern Tower of the Oxford Schools. A list of these tools was made. By 1710, the collection was in the Museum Savilianum.

The instruments disappeared by the 1920s. R. T. Gunther, the first curator of the Oxford Museum of the History of Science, tried to find them. He listed them as "not extant" (meaning they no longer existed). But in 1936, during renovations at the University Radcliffe Observatory, some old metal bars and plates were found. These turned out to be parts of the missing collection! They included a large mural quadrant and an astrolabe that belonged to Queen Elizabeth I. Greaves had taken this astrolabe on his trip to the Middle East.

The inscriptions on four of the instruments say:

- 1659 Acad. Oxon. in usum praecipue Prof. Savilianorum:

- Ex dono Nic Greaves S.T.D.

- In memoriam Tho. Bainbridge M.D. Jo Greaves A.M. N. fra: olim Astronomiae Prof. Savil.

This means: "1659, Oxford University, mainly for the use of the Savilian Professors: A gift from Nicholas Greaves, Doctor of Sacred Theology. In memory of Thomas Bainbridge, Doctor of Medicine, and John Greaves, Master of Arts, Nicholas's brother, formerly Savilian Professors of Astronomy."

Greaves' other, smaller astrolabe was found later in 1971 by Gunther's son. The inscription on its edge reads: '1659 . Acad. Oxon. Ex dono Nic Greaves. S.T.D.'

What John Greaves Wrote

Besides his articles in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, John Greaves' main books are:

- Pyramidographia, or a Description of the Pyramids in Ægypt (1646)

- A Discourse on the Roman Foot and Denarius (1647)

These books were printed again later as part of:

- Greaves, John (1737) Miscellaneous works of Mr. John Greaves Vol. I and Vol. II. These were published by Dr Thomas Birch. This also includes a reprint of:

- Withers, Robert (edited by John Greaves) A Description of the Grand Signour’s Seraglio; or Turkish Emperours Court (1653)

- Pyramidographia was translated into French and published in Relations de divers voyages curieux, qui n'ont point esté publiees... (1664). This book included Greaves' detailed drawings of the pyramids and mummies.

- Elementa linguae Persicae, authore Johanne Gravio: item anonymus Persa de siglis Arabum & Persarum astronomicis (1649) (This means Elements of the Persian language)

He also translated some works into Latin:

- Chorasmiae et Mawaralnahrae, etc. (1650). This was a description of Khwarezm and Mawarannahr (Transoxiana). He translated it from an Arabic writing by Abu'l-Fida. It included tables of latitude and longitude for the main towns. A copy is in Merton College Library.

- Abulfedae Peninsulam Arabum. This is a translated part of Abu'l-Fida's History.

- Binae Tabulae Geographicae, which means two tables of geographical latitudes and longitudes. He translated these from Persian writings by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Ulugh Beg.

These three works appeared in John Hudson's book (1712): Geographiae Veteris Scriptores Graeci Minores Vol. III, Oxon. (in Latin)

- Lemmata Archimedis, apud Graecos et Latinos iam pridem desiderata, e vetusto codice manuscripto Arabico. This is a translation of part of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi's edition of the so-called Middle Books. Greaves' unpublished writing was changed and improved after his death by Samuel Foster.

- Foster, Samuel (1659). Miscellanea sive lucubrationes mathematicae.

The following book might not be by John Greaves, even though his name is on the title page. It was first printed after his death in 1706 and again in 1727, with a second edition in 1745. It talks about Greaves' findings and measurements of the Roman foot and denarius.

- Greaves, John (1745) [1706]. The origin and antiquity of our English weights and measures discover'd... 2nd edition.

See also

In Spanish: John Greaves para niños

In Spanish: John Greaves para niños

- List of Gresham Professors of Geometry

- Pyramid inch