John Hansson Steelman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Hansson Steelman

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

Johan Hansson

1655 |

| Died | January 1, 1749 (aged 94) |

| Nationality | Naturalized citizen of British Colonial America |

| Occupation | Interpreter, fur trader |

| Years active | 1679-1740 |

| Known for | First permanent white settler in Pennsylvania west of the Susquehanna River |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Stalcop (c. 1666 - ?) |

| Relatives | Sons: John Hans Steelman Jr., Måns Steelman; Grandfather: Olof Persson Stille |

John Hansson Steelman (1655–1749) was born Johan Hansson in what is now Grays Ferry, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was also known as "Hance" Stillman or Tilghman. In 1693, he changed his name to John Hansson Steelman.

He became a successful fur trader and interpreter. He worked with Native American tribes like the Shawnee, Susquehannock, and Piscataway in Maryland and Pennsylvania. John Hansson Steelman also gave a lot of money to help build the Holy Trinity Church (Old Swedes) Church. He died in 1749 in Adams County, Pennsylvania, when he was 94 years old.

Contents

John Hansson Steelman's Family

His Father, Hans Månsson

John's father, Hans Månsson (1612-1691), was born in Skara Municipality, Sweden. He was a soldier before coming to America. In 1640, he got into trouble for cutting down apple and cherry trees in a royal garden.

He was given a choice: face punishment or sail to New Sweden in America. Hans Månsson chose to go to New Sweden. He arrived in November 1641 on a ship called the Charitas.

After working for six years, Hans Månsson became a free man in 1647. He became a respected leader in New Sweden. In 1653, he and 21 others signed a petition against the strict governor, Johan Printz.

In 1654, Hans Månsson married Ella Stille. She was a widow with two children. They had six sons together, and John Hansson was their first son, born in 1655. Hans Månsson received a large piece of land in what is now Kingsessing, Philadelphia. He also became a captain in the militia.

In 1674, Hans Månsson bought land in New Jersey and became one of the first white settlers there. He died in 1691 in Cinnaminson Township, New Jersey.

His Mother, Ella Stille Steelman

Ella Stille (1634-1718) was the oldest daughter of Olof Persson Stille. Her first husband died in 1654. She then married Hans Månsson later that year. Hans Månsson took care of her two children as his own.

Ella and Hans had six more sons, including John Hansson. After Hans Månsson died in 1691, Ella and her sons started using the last name Steelman. This name came from combining her maiden name, Stille, and her husband's name, Måns. Ella died in 1718 in Gloucester County, New Jersey. She is buried at the Gloria Dei (Old Swedes') Church cemetery.

John Hansson Steelman's Family Life

John Hansson Steelman married Maria Stalcop in 1679 in New Castle, Delaware. Maria was born in 1666. They had at least five children, including three sons: John Hans Steelman, Jr., Måns Hans Steelman, and Peter Hans Steelman.

Becoming a Trader and Interpreter

In the mid-1670s, John Hansson moved with his parents to New Jersey. In 1679, he married Maria Stalcop. In 1687, he bought land with his brother-in-law, Peter Stalcop.

In 1693, Steelman and his family moved to Sahakitko, which is now Elk Landing in Cecil County, Maryland. Here, Steelman started his career as a trader with Native Americans.

In 1695, John Steelman and his oldest son, John Jr., became official residents of Cecil County, Maryland. By 1697, he was Maryland's main interpreter for dealing with Native American tribes. He was often called John Hance Tillman in Maryland records. Steelman also set up trade with the Shawnee people in Pennsylvania.

In 1697, Steelman reported to the Maryland Council about the Native American tribes living near Chesapeake Bay. He shared details about the number of men in the Susquehanna, Shawnee, and Delaware tribes. He also mentioned where they lived.

In 1698, a meeting was held at Steelman's trading house at Sahakitko. Officials from Maryland met with the chiefs of the Susquehannocks, Shawnees, and Delawares. The Shawnee king, Meaurroway, attended this important meeting.

Steelman continued to serve as an interpreter for important meetings. In 1701, he witnessed a treaty between William Penn and the Susquehannocks. This treaty gave land along the Potomac River to the English in exchange for protection and trade rights.

His Wealth and Business

By the late 1690s, John Hansson Steelman was quite wealthy. He gave a lot of money to help buy land and build the Holy Trinity Church (Old Swedes). He donated £100 as a gift and loaned £220. In return, he and his wife were promised the best seats in the church and burial inside it.

Between 1704 and 1711, Steelman bought over a thousand acres of land in Cecil County. He owned land near Port Deposit, Maryland, Octoraro Creek, and Conowingo Creek. He also set up a second trading post at Octoraro Creek. However, by 1714, it seems his wealth might have decreased, as some of his property was taken to pay a debt.

A Difficult Event in 1711

In 1711, a young man named Francis Le Tort, who was working for Steelman, ran away into the forest with some other workers. Steelman offered a reward to some Shawnee warriors to bring them back. Sadly, Francis Le Tort was killed.

An investigation was led by Deputy Governor Charles Gookin. The Shawnee chief, Opessa Straight Tail, explained that Steelman had asked him to send people to bring the runaways back or kill them. Opessa said he refused this request.

The governor cleared Opessa of responsibility for the death. Most of the Shawnee warriors involved in the killing were hunted down and killed. There is no record that Steelman faced any punishment for this event.

Challenges with Colonial Leaders

John Hansson Steelman became the most successful trader in northern Maryland. Many Native American communities preferred to trade with him. This started to affect the profits of traders in Pennsylvania.

By 1701, William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania, felt that Steelman should get a trading license from Pennsylvania. This was because Steelman was doing so much business across the Pennsylvania-Maryland border. In April 1701, Penn had Steelman's trade goods taken in Philadelphia.

Penn wrote to Steelman about the seized goods. He told his Council that Steelman was trading in Pennsylvania without a license. This was against the law and hurt Pennsylvania's trade.

In 1705, Steelman planned to open a trading post at Conestoga. This worried the Pennsylvania authorities. James Logan, a government official, visited the Native Americans at Conestoga. He asked them not to let any white settlers build homes or trade posts without the governor's permission.

John Hansson Steelman's Home and Trading Post

In 1693, Steelman moved to Sahakitko, which is now Elkton, Maryland. He first built a log cabin and then a stone house. This became his main home and trading base. The stone house was likely finished by 1697.

From 1693 until about 1720, Elk Landing was Steelman's center of operations. He traded manufactured goods for animal furs with the Shawnee, Susquehannock, Piscataway, and Lenape tribes.

The trading likely happened in the basement of the stone house. It had a large, arched doorway facing the creek. There was probably a dock where goods were loaded and unloaded.

Steelman's house had four levels, including the basement for trading. It had two main living floors and an attic for sleeping or playing. The house had six Swedish-style corner fireplaces, and five of them are still there today. It also had thirteen large windows, which showed his wealth because glass was very expensive.

The first log cabin Steelman lived in was next to the stone house. It was later used as a kitchen and may have been a sauna or smokehouse. It was taken down around 1905.

The stone house at Elk Landing was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. A group called the Historic Elk Landing Foundation has worked to protect and restore the site. The house was restored in 2009.

Moving Westward

By 1720, John Hansson Steelman moved west to what is now Adams County, Pennsylvania. He continued his trading business there. He was the first white settler in that part of the country.

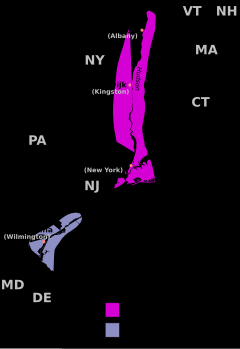

He had to move his business because his Native American customers, the Shawnee and Lenape, were moving westward. This was due to more settlers arriving, forests being cut down, and game becoming scarce. By 1724, he had a trading post in Carroll County, Maryland. By 1730, he was back in Adams County. In 1737, he was one of the people who signed the Walking Purchase treaty with the Delaware Indians.

His Testimony in a Land Dispute

In 1740, when he was 85 years old, Steelman gave testimony in a land dispute between the Penn family and Maryland. This dispute was about the border between the two colonies. Steelman's testimony focused on the location of an old Susquehannock fort, which was important for defining the border.

He explained that he knew the area well. He described the difference between an "Indian Town" (a group of houses) and an "Indian Fort" (a town with a protective wall of poles and earth). He said he had seen an Indian town and fort near the mouth of Octoraro Creek about 40 or 50 years earlier. He also mentioned seeing the ruins of another fort where a big battle had been fought.

Because of his testimony, Steelman was given 200 acres of land in Adams County in 1741.

His Later Years and Legacy

John Hansson Steelman died in Adams County in 1749, at the age of 94. His belongings were sold at an auction for a small amount of money. His youngest son, Peter Hans Steelman, bought most of the items, including the Elk Landing property.

The exact date of his wife Maria Stalcop Steelman's death is not known. Many of John Hansson Steelman's descendants have kept a double last name, "Hans Steelman."

Remembering John Hansson Steelman

In November 1924, a historical marker honoring John Hansson Steelman was put up in Liberty Township, Adams County, Pennsylvania. This was on the land he received after his testimony in 1740. The original marker was stolen in 1973. A new one was placed there in 1977, near the Maryland State Line, on Steelman Marker Road.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |