Johnstown Flood facts for kids

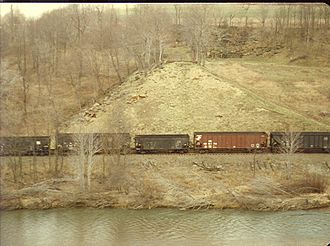

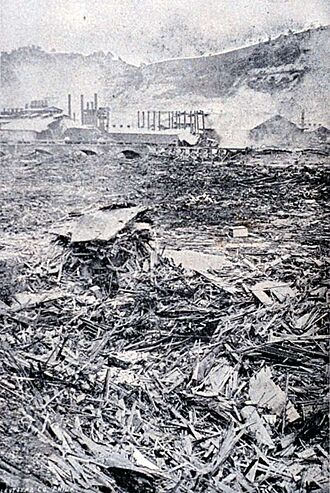

Debris of Stone Bridge in Johnstown following the flood

|

|

| Date | May 31, 1889 |

|---|---|

| Location | South Fork, East Conemaugh, and Johnstown in Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Deaths | 2,208 |

| Property damage | US$17,000,000 (equivalent to $553,696,296 in 2022) |

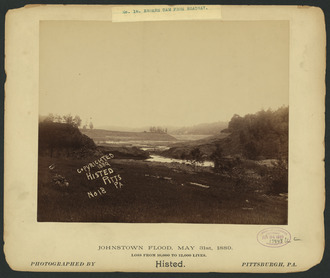

The Johnstown Flood, also known as the Great Flood of 1889, happened on Friday, May 31, 1889. It was caused by the terrible failure of the South Fork Dam. This dam was located on the Little Conemaugh River, about 14 miles (22.5 km) upstream from the town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in the United States.

The dam broke after several days of very heavy rain. It released 14.55 million cubic meters of water. This huge amount of water moved as fast as the average flow of the Mississippi River. The flood killed 2,208 people and caused about $17 million in damage.

The American Red Cross, led by Clara Barton, helped a lot with fifty volunteers. People from all over the U.S. and eighteen other countries sent help. After the flood, survivors tried to get money for their losses from the dam's owners. They usually lost in court. This led to a change in American law, making it easier to hold people responsible for such disasters.

Contents

History of the Johnstown Flood

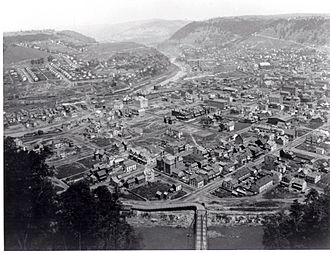

The city of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, was started in 1800 by Joseph Johns. It was built where the Stonycreek and Little Conemaugh rivers meet. The city grew quickly with the building of the Pennsylvania Main Line Canal in 1836. Later, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Cambria Iron Works were built in the 1850s.

By 1889, Johnstown had about 30,000 people. Many immigrants from Wales and Germany worked in its steel industries. The city was famous for its high-quality steel.

Johnstown was in a narrow valley with steep hills. The Allegheny Mountains were to the east. This area got a lot of rain and snow runoff. The city was often flooded because of its location on the rivers. Also, waste from the steel mills was dumped into the river. This made the river narrower and made the city even more likely to flood.

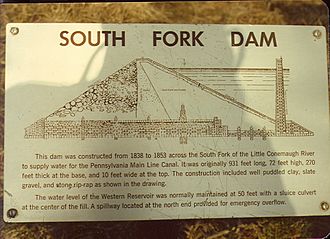

The South Fork Dam and Lake Conemaugh

The South Fork Dam was built between 1838 and 1853 by Pennsylvania. It was part of a canal system across the state. Johnstown was at one end of the canal. Water for the canal came from Lake Conemaugh, a large reservoir behind the dam.

When railroads became more popular than canals, Pennsylvania sold the canal system to the Pennsylvania Railroad. The railroad then sold the dam and lake to a private group.

Henry Clay Frick and other wealthy people from Pittsburgh bought the dam and lake. They wanted to turn it into a private resort for their rich friends. Many of these friends were connected to Carnegie Steel. They made changes to the dam, like lowering it by 3 feet (0.9 m) to build a road on top. They also put a fish screen in the spillway, which is a channel for water to flow out.

These changes made the dam weaker. Also, the original dam had pipes and valves to let water out in an emergency. These had been sold for scrap and were not replaced. So, the club had no way to lower the lake's water level if it got too high.

The Pittsburgh group built cottages and a clubhouse. They created the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. It was a very private mountain getaway. Lake Conemaugh was about 450 feet (137 m) higher than Johnstown. The lake was about 2 miles (3.2 km) long, 1 mile (1.6 km) wide, and 60 feet (18 m) deep near the dam. The dam itself was 72 feet (22 m) high and 931 feet (284 m) long.

Events of the Johnstown Flood

On May 28, 1889, a storm began over Nebraska and Kansas. By May 30, it brought the heaviest rainfall ever recorded in western Pennsylvania. Between 6 to 10 inches (150 to 250 mm) of rain fell in 24 hours. Small creeks became raging rivers, tearing out trees. Telegraph lines and rail lines were destroyed. By morning, the Conemaugh River in Johnstown was about to overflow.

On the morning of May 31, Elias Unger, the club president, saw Lake Conemaugh was dangerously high. He gathered men to clear the spillway, which was blocked by a broken fish trap and debris. Other men tried to dig a ditch to let water out, but it didn't work. They tried to pile mud and rock on the dam to save it.

John Parke, an engineer, thought about cutting the dam to release water, but decided against it. He sent warnings to Johnstown by telegraph. However, these warnings were not taken seriously. There had been many false alarms before. Unger and his men worked until about 1:30 p.m., then gave up. They moved to higher ground to watch. In Johnstown, the water in the streets rose to 10 feet (3 m), trapping people.

Between 2:50 and 2:55 p.m., the South Fork Dam broke. The lake held 14.55 million cubic meters of water. It took about 65 minutes for most of the lake to empty. The first town hit was South Fork. Most people escaped to nearby hills. About 20 to 30 houses were destroyed, and four people died.

The water rushed downstream, picking up trees, houses, and animals. At the Conemaugh Viaduct, a 78-foot (24 m) high railroad bridge, the flood was stopped for a moment by debris. But in seven minutes, the bridge collapsed. This delay made the flood hit places downstream even harder.

The small town of Mineral Point, 1 mile (1.6 km) below the viaduct, was hit next. After the flood, nothing was left but the bedrock. About sixteen people died there. Studies in 2009 showed the flood's flow rate was over 12,000 cubic meters per second. This is similar to the Mississippi River's flow at its delta.

The village of East Conemaugh was the next victim. A witness said the water looked like "a huge hill rolling over and over." A train engineer named John Hess heard the flood coming. He put his locomotive in reverse and blew the whistle constantly. His warning saved many people. The flood picked up his moving locomotive and floated it away. Hess survived, but at least fifty people died, including passengers on stranded trains.

Before reaching Johnstown, the flood hit the Cambria Iron Works in Woodvale. It swept up railroad cars and barbed wire. Of Woodvale's 1,100 residents, 314 died. Boilers exploded at the Gautier Wire Works, sending black smoke into the sky. Miles of barbed wire got tangled in the flood's debris.

Fifty-seven minutes after the dam broke, the flood hit Johnstown. People were surprised by the wall of water and debris. It moved at 40 mph (64 km/h) and was 60 feet (18 m) high in some places. Many people were crushed by debris or caught in barbed wire. Others drowned. Those who reached attics, roofs, or floating debris waited hours for help.

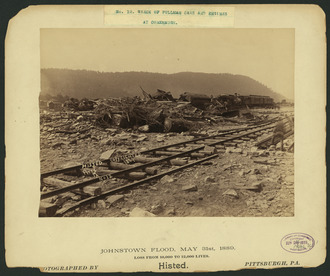

At Johnstown, the Stone Bridge carried the Pennsylvania Railroad. Debris piled up against the bridge, forming a temporary dam. This caused the flood to surge upstream along the Stoney Creek River. Then, the water rushed back, hitting the city a second time from a different direction. Some people trapped at the bridge died in a fire that burned for three days. The debris pile at the bridge was 30 acres (12 ha) wide and 70 feet (21 m) high. It took three months to clear it, partly because of the tangled barbed wire.

Victims of the Flood

The flood killed 2,208 people. This made it the largest loss of civilian life in the U.S. at that time. Later, the 1900 Galveston hurricane and the 9/11 attacks caused more deaths. One man, Leroy Temple, was thought to be dead but survived. He returned to Johnstown eleven years later. He had escaped the debris at the Stone Bridge and moved away.

Investigation and Legal Aftermath

Five days after the flood, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) started an investigation. They looked at the dam's design and changes made to it. They also talked to people who saw what happened. Their report was finished in 1890 but was kept secret for a while. It was finally published in 1891.

The ASCE committee said the dam would have failed anyway, even without the changes. However, later studies disagreed. A 2016 study confirmed that the changes made by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club made the dam much weaker. Lowering the dam and not replacing the discharge pipes greatly reduced its ability to handle heavy storms.

After the disaster, some survivors blamed the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. They said the club did not take care of the dam properly. The club was defended in court by lawyers who were also club members. They argued that the flood was a "natural disaster" or an "Act of God". No money was paid to the flood survivors by the club.

This unfair situation helped change American law. Later, courts started to accept "strict liability". This means someone can be held responsible for damage even if they weren't careless, especially if they used their land in an unusual way.

Even though the club wasn't held legally responsible, many wealthy members helped Johnstown recover. Henry Clay Frick and about half the club members gave thousands of dollars. Andrew Carnegie built a new library for the town.

Aftermath of the Flood

Immediately After

The Johnstown Flood was the worst flood in the U.S. in the 1800s. About 1,600 homes were destroyed. The damage was about $17 million (which would be about $497 million today). Four square miles (10 km²) of downtown Johnstown were completely ruined. The debris at the Stone Bridge covered 30 acres (12 ha). Cleanup took years. The Cambria Iron and Steel factories were badly damaged but were back to full production in 18 months.

Workers built a temporary wooden bridge to replace the destroyed Conemaugh Viaduct. The Pennsylvania Railroad restored service to Pittsburgh by June 2. Food, clothing, and medicine arrived by train. Johnstown's first request for help was for coffins and undertakers. A demolition expert, "Dynamite Bill" Flinn, and his 900-man crew cleared the wreckage at the Stone Bridge. They also helped distribute food and build temporary homes. About 7,000 relief workers helped at the peak.

Clara Barton, who started the American Red Cross, arrived on June 5, 1889. She led the Red Cross's first major disaster relief effort. She stayed for over five months. Donations came from all over the U.S. and 18 other countries. Over $3.7 million was collected for Johnstown relief.

Frank Shomo, the last known survivor of the 1889 flood, died in 1997 at age 108.

-

A copy of the previous picture was later used for the 1900 Galveston hurricane

Later Floods

Johnstown has had many floods since 1889. Major floods happened in 1894, 1907, 1924, 1936, and 1977. The biggest flood in the first half of the 1900s was the St. Patrick's Day flood of March 1936. After this flood, the United States Army Corps of Engineers made the Conemaugh River deeper and built concrete walls. They said Johnstown was "flood free."

The new river walls held up during Hurricane Agnes in 1972. But on July 19, 1977, a severe thunderstorm dropped 11 inches (280 mm) of rain in eight hours. The rivers rose again. By morning, the city was under 8 feet (2.4 m) of water. This flood caused $200 million in damage and killed 78 people. Forty people died when the Laurel Run Dam failed. About 50,000 people lost their homes. Markers on City Hall show the height of the 1889, 1936, and 1977 floods.

Legacy of the Johnstown Flood

At Point Park in Johnstown, where the Stonycreek and Little Conemaugh rivers meet, an eternal flame burns. It remembers the flood victims.

The Carnegie Library in Johnstown is now the Johnstown Flood Museum. It is run by the Johnstown Area Heritage Association.

Parts of the Stone Bridge are now part of the Johnstown Flood National Memorial. This memorial was created in 1969 and is managed by the National Park Service. The bridge was restored in 2008.

The Johnstown Flood, along with the failure of the Walnut Grove Dam a year later, made people pay more attention to dam safety across the country.

How it Changed American Law

Survivors of the flood could not win money in court from the South Fork Club. The club's money was set up to protect the owners' personal wealth. Also, it was hard to prove that any specific owner was careless. This situation was criticized a lot in newspapers.

Because of this criticism, state courts in the 1890s started using a British law idea called Rylands v. Fletcher. This idea says that someone can be responsible for damage even if they weren't careless, if the damage came from an unusual use of their land. This helped lead to the idea of "strict liability" in the legal system.

Johnstown Flood in Media

The Johnstown Flood has been shown in many films, TV shows, plays, songs, and books.

Film and Television

- The Johnstown Flood (1926) is a silent film.

- The Johnstown Flood (1946) is an animated film where Mighty Mouse stops the flood.

- The movie Slap Shot (1977), filmed in Johnstown, mentions a "1938 flood."

- The Johnstown Flood (1989) is a short documentary that won an Academy Award.

- The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles TV show mentions the flood in an episode.

Theater

- A True History of the Johnstown Flood by Rebecca Gilman is a play.

- In the early 1900s, shows about the flood used moving scenery and lights. They were popular at exhibitions, seen by hundreds of thousands of people.

Music

- The song "Mother Country" by John Stewart (1969) talks about men standing in the Johnstown mud.

- Bruce Springsteen's song "Highway Patrolman" (1982) mentions a song called "Night of the Johnstown Flood."

- The album "Flood City Trax" by "Nondi_" is about living in Johnstown and poverty.

Literature

Poems

- "The Pennsylvania Disaster" by William McGonagall is a poem.

- "By the Conemaugh" by Florence Earle Coates is another poem.

Short Stories

- Brian Booker's "A Drowning Accident" (2005) is based on the flood.

- Caitlín R. Kiernan's "To This Water (Johnstown, Pennsylvania, 1889)" (1994) features the flood.

- Donald Keith's Mutiny in the Time Machine (1962) has Boy Scouts traveling back to the flood.

Historical Works

- Willis Fletcher Johnson wrote History of the Johnstown Flood (1889), likely the first book about it.

- Gertrude Quinn Slattery, a survivor, wrote a memoir called Johnstown and Its Flood (1936).

- Historian David McCullough's first book was The Johnstown Flood (1968).

- Weatherman Al Roker wrote Ruthless Tide: The Heroes and Villains of the Johnstown Flood (2018).

In Fiction

- Rudyard Kipling's novel Captains Courageous (1897) mentions the flood.

- Marden A. Dahlstedt's young adult novel The Terrible Wave (1972) is inspired by a survivor's memoir.

- John Jakes's novel The Americans (1979) features the flood.

- Kathleen Cambor's historical novel In Sunlight, In a Beautiful Garden (2001) is based on the flood.

- Peg Kehret's fantasy novel The Flood Disaster has students travel back in time to the flood.

- Murray Leinster's novel The Time Tunnel (1967) features time travelers who can't warn people about the flood.

- Catherine Marshall's novel Julie has events similar to the Johnstown Flood.

- Richard A. Gregory's The Bosses Club (2011) is a historical novel about the flood.

- Judith Redline Coopey wrote Waterproof: A Novel of the Johnstown Flood (2012).

- Kathleen Danielczyk wrote Summer of Gold and Water (2013).

- Colleen Coble wrote The Wedding Quilt Bride (2001), a romance set during the flood.

- Michael Stephan Oates wrote Wade in the Water (2014), a coming-of-age story during the flood.

- Jeanette Watts's Wealth and Privilege (2014) shows the club and the flood.

- Mary Hogan's The Woman In the Photo (2016) connects present-day Johnstown with 1889.

- Jane Claypool Miner wrote Jennie (1989), a historical romance about a girl who survives the flood.

See also

In Spanish: Inundación de Johnstown para niños

In Spanish: Inundación de Johnstown para niños

- St. Francis Dam disaster

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |