Joseph Priestley House facts for kids

|

Joseph Priestley House

|

|

Priestley Avenue side of the Joseph Priestley House in 2007

|

|

| Location | Northumberland, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Area | 1 acre (0.40 ha) |

| Built | 1794 - 1798 |

| Architectural style | Georgian, Federal |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000673 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | January 12, 1965 |

| Designated NHL | October 15, 1966 |

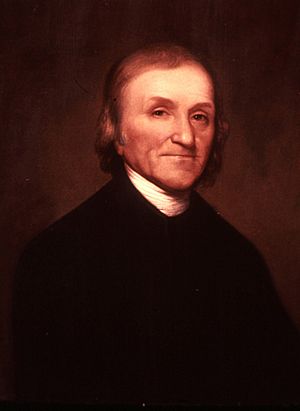

The Joseph Priestley House was the American home of Joseph Priestley (1733–1804). He was a famous British thinker, scientist, and teacher. Priestley lived in this house in Northumberland, Pennsylvania, from 1798 until he passed away. His wife, Mary, designed the house. It has a mix of Georgian and Federalist styles.

The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC) ran the house as a museum for Joseph Priestley from 1970. It closed in August 2009 because not many people visited and there were budget cuts. However, the house reopened in October 2009. The PHMC still owns it, but the Friends of Joseph Priestley House (FJPH) now manage it.

The Priestley family moved to the United States in 1794. They were trying to escape religious problems and political unrest in Britain. They wanted a peaceful life away from city problems. Even so, Joseph Priestley faced political arguments and family troubles during his last ten years.

After the Priestleys died, their home was privately owned for many years. In the early 1900s, a professor named George Gilbert Pond bought it. He wanted to create the first Priestley museum. Sadly, he died before finishing his project. The house was finally restored in the 1960s by the PHMC. It was then named a National Historic Landmark.

Another big renovation happened in the 1990s. The goal was to make the home look exactly as it did when Priestley lived there. The American Chemical Society often celebrates important events at the house. They have marked the 100th and 200th anniversaries of Priestley's discovery of oxygen gas. They also celebrated his 250th birthday.

Contents

Where is the Joseph Priestley House?

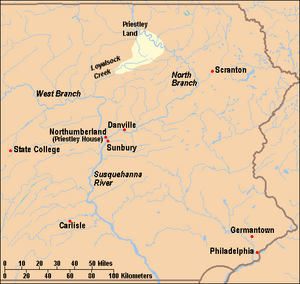

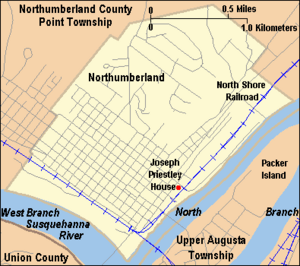

The Joseph Priestley House is in Northumberland, Pennsylvania. This area became a village in 1772. It was built on land bought from the Iroquois people. After the French and Indian War, many European immigrants settled here.

During the American Revolution, the village was empty for a while. People returned in 1784. When the Priestleys moved there in 1794, it was a small town. It had about 100 houses and a few businesses. There were also meeting houses for different religious groups.

The Priestleys bought their land in 1794 for £500. Today, the house and its land cover 1 acre (4,000 m2). The address is 472 Priestley Avenue. This street was once called "North Way." It was renamed to honor Joseph Priestley.

The house faces the Susquehanna River. The West Branch Susquehanna River joins the main river branch nearby. The property is about 456 feet (139 m) above sea level.

The property used to be twice as big. Around 1830, the Pennsylvania Canal (North Branch Division) was built. It cut through the front yard, making the property smaller. Later, a railroad line was built near the house. The canal closed in 1902 and was filled in. Today, a modern railroad line follows the old canal path.

Why the Priestleys Came to America

The last few years the Priestleys spent in Britain were very difficult. In 1791, during the Birmingham Riots, their home was burned down. Joseph's church and the homes of other religious Dissenters were also destroyed. The Priestleys tried to live in London, but the political problems continued.

In 1794, they decided to move to America. About 10,000 people moved from Europe to America around this time. The Priestleys left Britain in April and arrived in New York City in June 1794. Two of their sons had already moved to the U.S. in 1793.

Americans knew Priestley as a supporter of religious freedom. He also supported American independence. When he arrived, many political groups wanted his support. But Priestley wanted to avoid political arguments. He wrote that he would "take no part whatever in the politics of a country in which I am a stranger." He never became a U.S. citizen. He also turned down a job teaching chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania.

On their way to Northumberland, the Priestleys stopped in Philadelphia. Joseph gave several sermons there. These sermons helped spread Unitarianism in America. Priestley inspired many Unitarian groups to form. He helped found at least twelve congregations in different states.

Priestley enjoyed preaching in Philadelphia. However, living there was too expensive. He also disliked the city's Quakers, thinking they were too fancy. He was also worried about a yellow fever outbreak in the city.

He thought about settling in Germantown. It had better transportation and communication. But his wife, Mary, preferred the countryside. She wanted to be near their sons. Priestley decided to settle in Northumberland by July 1794. It was a "five days of rough travel" north of Philadelphia. They hoped their new community would grow.

Life in Northumberland

Priestley found Northumberland a bit too quiet. He wrote that it was "almost out of the world." He complained that he had to wait a week for news. He missed his old life in England. He often called himself an "exile."

His wife, Mary, was happier. She wrote that she was "thankful to meet with so sweet a situation and so peaceful a retreat." She liked the beautiful views of woods and water. She also found the people "plain and decent."

Priestley's son, Joseph Priestley Jr., was part of a group that bought a lot of land. A friend of Joseph Priestley, Thomas Cooper, wrote a pamphlet. It encouraged others to move to Pennsylvania. It gave advice on how to settle there.

Some poets, like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, wanted to move to America. They planned to create a perfect community called "Pantisocracy." They were inspired by Priestley's story. But they could not raise enough money. So, they never moved to America. Few immigrants came to Northumberland from Cooper's plans.

After these plans failed, Priestley tried to convince other friends to move to Northumberland. But no one did. Priestley wrote that he decided to stay because he and his wife liked the place. He also said Philadelphia was too expensive. Northumberland was cheaper. He felt his sons would be safer there.

Priestley's Later Years

Priestley tried to avoid political problems in the U.S., but it was hard. A journalist named William Cobbett wrote false accusations against him. Cobbett claimed Priestley was causing trouble in Britain. He also tried to make Priestley's science seem unreliable.

Family problems also made his life difficult. His youngest son, Harry, died in December 1795. He likely died from malaria. Mary Priestley died in September 1796. She was already sick and never recovered from her son's death. Joseph wrote that she had "taken much thought in planning the new house."

Priestley continued his work in education. He helped start a "Northumberland Academy." He also gave his large library to the new school. He exchanged letters with Thomas Jefferson about how to set up a university. Jefferson used Priestley's advice when he founded the University of Virginia.

Priestley also kept up his scientific research. He was supported by the American Philosophical Association. However, he lacked news from Europe. This meant he was not always aware of the newest scientific discoveries. Most of his work focused on defending older theories. But he did some new research on spontaneous generation and dreams.

By 1801, Priestley became very ill. He could no longer write or do experiments well. On February 3, 1804, he tried one last experiment but was too weak. He died three days later. He was buried in Riverview Cemetery in Northumberland.

House Design and Features

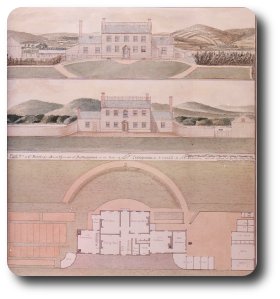

Joseph and Mary lived in a small house with their son's family while their new home was being built. Mary Priestley was the main designer of the new house. Her family's money might have helped pay for it. Sadly, she died before it was finished.

Joseph's laboratory was the first part of the house to be completed, in 1797. It was the first lab he designed and built himself. It was likely the first "scientifically-equipped laboratory" in the United States. In this lab, Joseph continued his work. He identified carbon monoxide, which he called "heavy inflammable air."

In 1798, Joseph Jr. and his family moved into the new house with Joseph Priestley. The house also held Priestley's library. It had about 1600 books when he died. This was one of the largest libraries in America at the time. The Priestley family held Unitarian church services in the drawing room. Joseph also taught a group of young men there.

The main house was finished in 1798. It was built in an 18th-century Georgian style. This style is known for its "balance and symmetry." The house also had Federalist touches. These included fanlights over the doors and railings on the roof. These details made it look distinctly American.

The house has a central section with two and a half stories. It is 48 feet (14.6 m) by 43 feet (13.1 m). On each side, there are one-story wings. The north wing was the laboratory. The south wing was the summer kitchen. The house has a total area of 5,052 square feet (469 m2).

The house is made of wood, covered with white clapboards. It sits on a stone foundation. The Priestleys used wood because stone or brick was not available. Joseph wrote that he preferred a house made of such wood. This led a journalist to call the house a "shed."

The central part of the house has a slate roof. It also has a deck with a railing on top. There are three chimneys. The house faces the Susquehanna River. Both the front and back doors have a small porch. A circular driveway leads to the front door.

The house was built to have beautiful views of the river. Priestley built a high wall to block the view of Northumberland town. He added a belvedere to the roof to see the landscape better. His gardens were a smaller version of the gardens at Bowood House, where he used to work.

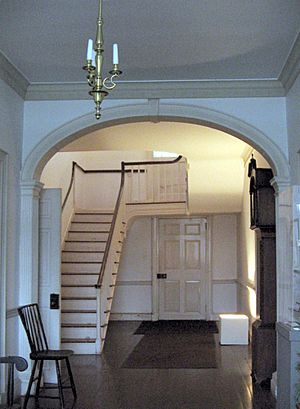

Building the house was hard because there were not many skilled workers in Northumberland. For example, the main staircase might have been put together from a kit. It is one step too short for the hallway. This shows the lack of skilled labor.

The House as a Museum

After Mary and Joseph Priestley died, their son Joseph Priestley, Jr. lived in the house. He sold it in 1811 when he moved back to Britain. The house was owned by many different people throughout the 1800s. In 1911, the last private resident moved out. The house was then rented to the Pennsylvania Railroad for its workers. This caused the house and grounds to decline.

Professor George Gilbert Pond was the first to try and make the Priestley House a museum. He bought the house at an auction in 1919 for $6,000. Pond wanted to move the house to Pennsylvania State College (now Pennsylvania State University). He thought a new railroad line would destroy it. But he died in 1920 before he could move it. The house was too fragile to move anyway.

The college kept the house as a museum. In 1926, a small brick building was built on the grounds. It was meant to be a fireproof museum for Priestley's books and tools. In 1955, the college gave the house to the town of Northumberland. From 1955 to 1959, it was both the town hall and a museum.

The house was too expensive for the town to keep. So, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania bought it in 1961. In 1968, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC) began restoring it. The museum opened to the public in October 1970. The renovations included restoring the laboratory. They also removed later additions to make it look original.

The Friends of the Joseph Priestley House (FJPH) help the PHMC. They assist with tours, special events, and museum work. Between 1998 and 1999, a big renovation happened. The goal was to make the grounds look exactly as they did when Priestley lived there. They rebuilt the carriage barn, hog sties, and gardens. These were based on old drawings and records.

Priestley did not write much about his laboratory. But researchers learned a lot about 18th-century labs. In 1996, excavations found two underground ovens. They also found signs of a simple fume hood. The 1998 renovations restored the lab to its original state.

After Joseph's death, some of his tools and belongings were sold to Dickinson College. The college displays them each year. The house lost its original furniture when Joseph Jr. moved back to England. So, the house is now furnished with items donated by Priestley's family. It also has items similar to those he owned. These include his balance scales and microscope.

On January 12, 1965, the Joseph Priestley House became a National Historic Landmark. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) on October 15, 1966. In 1994, the American Chemical Society named it a National Historic Chemical Landmark. Many of Priestley's descendants attended the ceremony.

The Northumberland Historic District was listed on the NRHP in 1988. It includes the Priestley House. The district also has the Priestley-Forsyth Memorial Library. This library was once an inn. The Joseph Priestley Memorial Chapel was built in 1834 by Priestley's grandson. It is home to a Unitarian Universalist church.

The museum was open ten months a year under the PHMC. In 2007 and 2008, about 1,700 people visited each year. In March 2009, the PHMC suggested closing the house. This was due to low visitors and budget problems. Despite protests, the state closed the house in August 2009.

The Friends of the Joseph Priestley House then offered to help. They submitted a plan to operate the house with volunteers. On September 24, 2009, the PHMC and FJPH signed an agreement. The house reopened on October 3, with volunteers. The agreement lets FJPH manage programs and fees. On November 1, a "grand reopening celebration" was held.

In November 2010, the brick Pond building was rededicated. It had an $85,000 renovation. This included new roofing, heating, and accessibility. The FJPH plans to add a timeline of Priestley's scientific work there. They also plan a video about his lab techniques.

American Chemical Society Celebrations

The American Chemical Society (ACS) often uses the Joseph Priestley House for special events. On July 31 and August 1, 1874, 77 chemists visited the site. They celebrated the 100th anniversary of chemistry. This date marked Priestley's experiment of making oxygen. This meeting is seen as the first National Chemistry Congress. It led to the ACS forming two years later.

On September 5, 1926, about 500 ACS members met at the home again. They dedicated the small brick museum. They also celebrated the meeting 50 years earlier. Representatives from the ACS were at the museum's dedication in October 1970.

On April 25, 1974, about 400 chemists visited the home. The Priestley Medal, the ACS's highest honor, was given out there. On August 1, 1974, over 500 chemists celebrated "Oxygen Day" at the house. In October 1976, the ACS celebrated its own 100th anniversary in Northumberland. A replica of Priestley's lab equipment was given to the house.

On April 13, 1983, the ACS President spoke at the house. This was to celebrate Priestley's 250th birthday. It was also for a new Joseph Priestley stamp. In 2001, the ACS met again at the house. They celebrated the society's 125th anniversary. They even re-enacted parts of the 1874 and 1926 celebrations.

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |