Kaikōura Peninsula facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kaikōura Peninsula |

|

|---|---|

Aerial view of the Kaikōura Peninsula

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Quaternary |

| Mountain type | Limestone, mudstone |

The Kaikōura Peninsula is a piece of land that sticks out into the Pacific Ocean in the northeast of New Zealand's South Island. It reaches about five kilometres into the sea. The town of Kaikōura is located on the northern side of this peninsula.

People have lived on the peninsula for a very long time. Māori have been here for about 1000 years. Europeans arrived in the 1800s, when they started hunting whales off the coast. After whale hunting stopped in 1922, whales began to thrive again. Now, the area is famous for whale watching, attracting many visitors.

The Kaikōura Peninsula is made of limestone and mudstone. These rocks were formed and then pushed up and changed over millions of years during the Quaternary period. The peninsula is in an area where the Earth's crust is very active, near the Marlborough Fault System.

Just 500 metres off the coast, to the south-east, is the Kaikōura Canyon. This is a huge underwater valley, 60 kilometres long and up to 1200 metres deep. It's shaped like a 'U' and is very active, connecting to a system of deep-ocean channels that stretch for hundreds of kilometres.

Contents

History of the Kaikōura Peninsula

The Kaikōura Peninsula has a rich history, especially with the Māori. They lived here for almost 1000 years. They used the peninsula as a base to hunt large birds called moa. They also gathered lots of crayfish from the shores.

According to Māori legends, the famous hero Māui is said to have fished up the giant fish that became the North Island from this very peninsula. The Māori also built strong forts on the high terraces of the peninsula. You can still see signs of these old forts today using special imaging technology.

In the 1800s, European whaling stations were set up in the area. Whalers hunted whales off the coast. But in more recent times, the whales have been allowed to recover and grow in numbers. Now, whale-watching is a popular activity, making the area a great place for ecotourism. Whales come to these waters because squid and other deep-sea creatures are brought up from the deep Hikurangi Trench to the surface by ocean currents and the steep seafloor.

How the Land Was Formed

The Kaikōura Peninsula is on the east coast of New Zealand's South Island. It's like a big, upside-down U-shape in the rocks, with two valleys on either side. The peninsula is made of two main types of sedimentary rock: Amuri Limestone (from the Palaeocene period) and Oligocene-aged mudstone. These rocks have been folded and slightly faulted, especially the limestone.

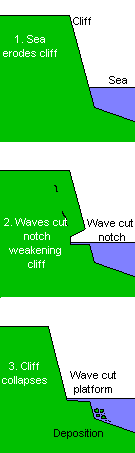

Along the shoreline, you can see flat rock areas called shore platforms. These are found in both the limestone and mudstone. The peninsula also has many flat, step-like terraces. These were once shore platforms that were lifted out of the sea by Earth's movements, called tectonic processes. The oldest terraces are at the top, and the youngest are near the Kaikoura town, right by the sea.

The Kaikōura Peninsula's shoreline faces the huge Pacific Ocean. This means it gets very strong waves and powerful ocean swells. Big storms can happen at any time of year. The tides here are moderate, with the water level changing by about 1.36 metres on average. The area has a temperate climate with moderate rainfall, about 865 mm per year. Temperatures usually range from 7.7° Celsius in July to 16.2° Celsius in January.

The shore platforms are constantly being shaped by strong ocean waves and weathering from the air. They can be from 40 metres to over 200 metres wide. The central parts of the peninsula have been lifted up by about 100 metres over the last 2.6 million years. This lifting happens because of earthquakes and changes in sea level. The most recent uplift happened during the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake on November 14, 2016. Another uplift likely happened around 1840, just before whalers arrived.

Scientists have found evidence of four major periods of land movement over the last 5,000 to 6,000 years. This shows that the shore platforms are always changing, reflecting both current processes and the area's recent geological past.

The Kaikōura Canyon

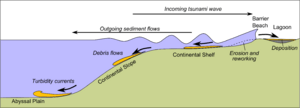

The Kaikōura Canyon is a large submarine canyon located southwest of the Kaikōura Peninsula. It's 60 kilometres long and can be up to 1200 metres deep. It has a 'U' shape and is very active. This canyon connects to a system of deep-ocean channels that wind for hundreds of kilometres across the ocean floor.

The Kaikōura Canyon is the main source of sediment for the 1500-kilometre-long Hikurangi Channel. This channel carries sand and mud to the Hikurangi Trench and other parts of the deep Pacific Ocean. The canyon is carved deeply into the narrow, tectonically active edge of the continent. It's believed to collect a lot of the sand and mud that rivers carry northwards along the coast from the active mountains of the South Island.

Tsunami Risk from Underwater Landslides

There is a known risk of a tsunami if an earthquake causes a large amount of sediment to slide at the mouth of the Kaikōura Canyon. Fine sand and silt are building up at the canyon head, with an estimated total volume of 0.24 cubic kilometres. If this sediment moves suddenly, it could create a tsunami close to the coast. This would be a big threat to coastal roads and houses.

It's not certain if tsunamis from this canyon have happened in the past. There isn't much geological evidence, and no specific studies have been done on ancient tsunamis here. However, some archaeological findings might suggest past ocean flooding. For example, ocean sediments have been found covering an old Maori settlement site on Seddon's Ridge, near South Bay. These deposits suggest that the sea flooded this area sometime in the last 150–200 years. This old village site, dating back about 650 years, also has signs of ocean flooding. While this evidence isn't definite proof, it does suggest that the ocean has flooded coastal settlements in the past, possibly from a very strong storm surge or a tsunami.

Sandy sediment builds up quickly on the steep slope of the canyon. Since this is an active earthquake zone, this sediment is likely to slide during moderately large earthquakes. Strong shaking from nearby faults could make the sandy sediment at the Canyon Head unstable and trigger large landslides. Experts estimate that an earthquake of magnitude 8 on the Richter scale or shaking equivalent to 'Moderate' on the Mercalli intensity scale would be enough to cause such an event.

The Kaikoura region is next to the Marlborough Fault System, which has several faults that could cause such an earthquake. The most likely are the Hope Fault, which used to be New Zealand's most active fault, and the larger Alpine Fault. The Hundalee Fault, though smaller, also ends near the Kaikoura coast and could trigger an underwater landslide. Based on past earthquake patterns, a major magnitude 8 earthquake or intensity V shaking at Kaikoura is estimated to happen about every 150 years.

There is evidence of past landslides in the Kaikōura Canyon. Cores taken from the canyon show many layers of sand and gravel from past sediment flows. It's estimated that the ground in Kaikoura town could shake with a peak acceleration of 0.44 g every 150 years. There haven't been any large earthquakes very close to Kaikōura since records began around 1840. However, dating of rock-falls suggests a major earthquake might have happened about 175 years ago. This matches the estimated time it takes for the current sediment deposits to build up at the canyon head. This suggests that sediment in the canyon head likely slid down as a major underwater current during that earthquake.

A landslide-generated tsunami poses a big risk to the area from South Bay to Oaro. Models show that if the entire landslide mass identified by scientists were to fail, it could cause very high tsunami waves along this coast. The effects could be even worse if such an event happened during a storm or high tide.

It's estimated that it takes about a century for enough sediment to build up in the canyon head to cause a major landslide. This means there is already enough sediment there to pose a significant danger. Cracks at the head of the modern sediment deposit show that it is likely to fail if there's a major earthquake. This failure would involve about a quarter of a cubic kilometre of loose sediment collapsing. The canyon-head gully faces northwards, towards the shore. This means that if a debris avalanche happens in the gully, the resulting tsunami would move towards the shore of South Bay and the southern side of the Kaikōura Peninsula.

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |