Kerma culture facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kerma Culture

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2500 BC–c. 1500 BC | |||||||

Kerma

|

|||||||

| Capital | Kerma | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| hkꜣw | |||||||

| History | |||||||

|

• Established

|

c. 2500 BC | ||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

c. 1500 BC | ||||||

|

|||||||

The Kingdom of Kerma or the Kerma culture was an ancient civilization. It was located in Kerma, a city in present-day Sudan. This kingdom thrived from about 2500 BC to 1500 BC in a region called ancient Nubia.

The Kerma culture started in the southern part of Nubia, known as "Upper Nubia." This area is now parts of northern and central Sudan. Over time, it grew northward into Lower Nubia, reaching the border of Egypt. Kerma was one of several important states along the Nile Valley during Egypt's Middle Kingdom period.

In its final stage (around 1700 to 1500 BC), Kerma became a large and powerful empire. It even took over the kingdom of Sai and was a strong rival to Egypt. However, around 1500 BC, the New Kingdom of Egypt conquered Kerma. Even after this, people in Kerma continued to rebel for many centuries. Later, around 1100 BC, the Kingdom of Kush appeared. This new kingdom, possibly linked to Kerma, helped Nubia regain its freedom from Egypt.

Contents

Discovering the Kerma Kingdom

The main site of Kerma is where the Kingdom of Kerma truly began. It includes a large town and a cemetery with huge burial mounds called tumuli. The wealth found at this site shows how powerful the Kingdom of Kerma was. This was especially true during the Second Intermediate Period, when Kerma posed a threat to Egypt's southern borders.

How Kerma Was Organized

Until recently, we only knew about the Kerma civilization from its main city and cemeteries. However, new studies and digs have found many more sites south of Kerma. Many of these were along old, dry channels of the Nile River. This shows that Kerma had a large population. It also helps us understand the political setup of the main city. Work done before building the Merowe Dam at the Fourth Cataract confirmed Kerma sites existed far upriver.

Kerma was clearly a big political power. Egyptian records describe its rich farmlands and many people. Unlike Egypt, Kerma seemed to be very organized from a central point. It controlled the Nile from the 1st to the 4th Cataracts. This meant its territory was as large as ancient Egypt's.

Most of the kingdom was made up of many small villages with crop fields. But some areas focused on raising animals like goats, sheep, and cattle. Gold mining was also an important business. Some Kerma towns were centers for collecting farm products and managing trade. Studies of cattle skulls found in royal Kerma tombs suggest that animals were brought from far away. This was likely a form of tribute from rural areas when Kerma's kings died. This shows how important cattle were to royalty in other parts of Africa later on.

People started farming in this region before the Kerma period, around 3500–2500 BC. The use of copper tools began in Kerma around 2200–2000 BC.

Only the cities of Kerma and Sai Island seemed to have large populations. Maybe more digs will find other important regional centers. At Kerma and Sai, there is much proof of rich leaders. There was also a group of officials who managed trade of goods from far-off lands. They also oversaw shipments sent from government buildings. Kerma clearly played a key role in trading luxury items from Central Africa to Egypt.

Kerma's History and Neighbors

Ancient Egyptian writings from the Old Kingdom (2700–2200 BC) show that Egypt had contact with early Nubia. They also show that early Nubian rulers existed. It seems these rulers were loyal to the kings of Egypt at first.

The last mention of an Egyptian Pharaoh in Sudan from the Old Kingdom was Neuserre (from the Fifth Dynasty) around 2400 BC. After this, there is no sign of an Egyptian presence in the area during the next Sixth Dynasty.

Regional Connections

The Gash Group was a culture that lived in Eritrea and Eastern Sudan from 3000 to 1800 BC. They had contact with Kerma throughout their history. Kerma items were found at Mahal Teglinos, the main site of the Gash Group.

For many centuries, the Gash people were part of the trade network between Egypt and the southern Nile Valley. This made Mahal Teglinos an important trading partner for Kerma. This trade helped complex societies grow in the region.

By 2300 BC, the Early C-Group culture also appeared in Lower Nubia. They likely came from the Dongola Reach, near Kerma. So, by the second millennium BC, Kerma was the center of a large kingdom. It was probably the first in the Eastern Sudan and was a rival to Egypt.

Kerma and Middle Kingdom Egypt

The Middle Kerma Period happened at the same time as the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (around 1990–1725 BC). During this time, Egypt began to conquer Lower Nubia. The Egyptian Pharaoh Senwosret I built forts at places like Ikkur, Quban, Aniba, Buhen, and Kor. The fort at Qubban protected gold mines in the Wadi Allaqi and Wadi Gabgaba areas.

Egypt's long history of military actions in Lower Nubia suggests that Kerma was seen as a threat. Egypt built strong forts in the middle Nile Valley during the Middle Kingdom. These forts were to protect Egypt's southern border from Kerma attacks. They also protected important trade routes between the two regions. Both during the Middle and New Kingdoms, Egypt wanted Kerma's resources. These included gold, cattle, milk products, ebony, incense, and ivory. Kerma's army was mainly made up of archers.

However, Egyptian control weakened during the 13th Dynasty and 2nd Intermediate Period. This was when Kerma grew the most and reached its largest size. Huge royal tombs were built in the city's burial ground. These tombs included many human sacrifices and secondary burials. Two large burial mounds had white quartzite cones. Kerma also had conflicts with Egypt in Lower Nubia.

At its peak, Kerma formed an alliance with the Hyksos and tried to defeat Egypt. Discoveries in 2003 at a tomb near Thebes show that Kerma invaded deep into Egypt between 1575 and 1550 BC. This is thought to be one of Egypt's most embarrassing defeats. Later pharaohs removed it from official history records. Many royal statues and monuments were taken from Egypt and moved to Kerma. This was likely a sign of victory by Kerma's ruler.

Kerma and New Kingdom Egypt

Under Thutmose I, Egypt launched several military campaigns south. They destroyed Kerma. This led to Egypt taking over Nubia (Kerma/Kush) around 1504 BC. Egypt then set up a southern border at Kanisah Kurgus, south of the Fourth Cataract. After the conquest, Kerma's culture became more like Egypt's. But rebellions continued for 220 years, until about 1300 BC. During the New Kingdom, Kerma/Kush became a very important part of the Egyptian Empire. It was important for trade, politics, and religion. Major Egyptian ceremonies were even held at Jebel Barkal, near Napata, which had a large Amun temple.

The New Kingdom of Egypt kept control of Lower and Middle Nubia. An official called the Viceroy of Kush, or 'King's Son of Kush', ruled the area. Egyptian settlements were built on Sai Island, Sedeinga, Soleb, Mirgissa, and Sesibi. Qubban continued to be important for gold mining in the Eastern Desert.

It's hard to know how much the Kingdom of Kerma and the later Kingdom of Kush were connected. The Kingdom of Kush started to appear around 1000 BC. This was about 500 years after the Kerma Kingdom ended. At first, the Kushite kings still used Kerma for royal burials and special events. This suggests some kind of link. Also, the design of royal burial sites in both Kerma and Napata (the Kush capital) are similar. Statues of Kush's pharaohs have also been found at Kerma. This shows that the rulers of Napata recognized a historical connection between their capital and Kerma.

What Language Did They Speak?

We don't know for sure what language the Kerma people spoke. Some experts think they spoke languages from the Nilo-Saharan family. Others believe they spoke languages from the Afro-Asiatic family.

Peter Behrens (1981) and Marianne Bechaus-Gerst (2000) suggest that the Kerma people spoke Afroasiatic languages, specifically from the Cushitic group. They point to words in the modern Nobiin language (a Nilo-Saharan language) that relate to animal herding. These words seem to come from an older Cushitic language. This suggests that the Kerma people, who lived in the Nile Valley before Nubian speakers arrived, spoke Afroasiatic languages.

However, Claude Rilly (2010, 2016) thinks the Kerma people spoke Nilo-Saharan languages. He believes these might be related to the later Meroitic language, which he also thinks was Nilo-Saharan. Rilly also disagrees with the idea that Afro-Asiatic languages had a big early influence on Nobiin. He believes there's stronger evidence that Nobiin was influenced by an older, now extinct, Eastern Sudanic language.

Julien Cooper (2017) also suggests that Nilo-Saharan languages from the Eastern Sudanic group were spoken by the Kerma people. He thinks this was true for people further south along the Nile and to the west, including those on Saï island (north of Kerma). But he believes Afro-Asiatic (likely Cushitic) languages were spoken by other groups in Lower Nubia. These include the Medjay and the C-Group culture, who lived north of Saï towards Egypt. They were also spoken by people southeast of the Nile in Punt in the Eastern desert.

Cooper looked at the sounds of place names and personal names from ancient texts. He argues that names from "Kush" and "Irem" (old names for Kerma and the region south of it) sound like Eastern Sudanic languages. But names from further north (Lower Nubia) and east sound more like Afro-Asiatic languages.

Cooper (2017, 2020) suggests that an Eastern Sudanic language (perhaps early Meroitic) was spoken at Kerma by at least 1800 BC. He thinks a change in place names for Upper Nubia in Egyptian texts around that time might show the arrival of a new group. However, Cooper also thinks a similar Eastern Sudanic language might have already been spoken in Upper Nubia earlier. This would include Kerma and the Saï area to its north. Meanwhile, north of Saï, in Lower Nubia, Cushitic languages were spoken. These were much later replaced by Meroitic. It is thought that early Meroitic spread, replacing both Eastern Sudanic and Cushitic languages along the Nile.

Archaeological Discoveries

Early Discoveries (20th Century)

When Kerma was first dug up in the 1920s, archaeologist George Andrew Reisner thought it was an Egyptian governor's base or fort. He believed these Egyptian rulers became the independent kings of Kerma. Reisner thought this because he found Egyptian statues with names in the large tombs. So, experts believed Kerma was just an Egyptian trading post. They thought it was too small and far from Egypt's known borders to be more directly connected.

However, starting in the mid-20th century, new digs showed that Kerma city was much bigger and more complex than thought. It also became clear that the items found and the burial customs were mostly from the local Kerma culture, not Egyptian.

Swiss archaeologist Charles Bonnet was one of the first to disagree with Reisner's ideas. He said it took 20 years for other Egyptologists to accept his arguments.

Newer Discoveries (21st Century)

In 2003, archaeologist Charles Bonnet led a team of Swiss archaeologists. They were digging near Kerma and found a hidden collection of huge black granite statues. These statues were of the Pharaohs from the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. They are now on display in the Kerma Museum. Among these sculptures were statues of the dynasty's last two pharaohs, Taharqa and Tanoutamon. These statues are described as "masterpieces that rank among the greatest in art history."

Scientists also studied the skulls of Kerma people. They compared them to other ancient groups in the Nile Valley and North Africa. They found that the Kerma people were very similar in skull shape to early Egyptians from Naqada (4000–3200 BC). They were also somewhat related to later Egyptians from Gizeh (323 BC – AD 330) and early Egyptians from Badari (4400–4000 BC).

Studies of dental traits (teeth) in Kerma fossils showed connections to various groups in the Nile Valley, Horn of Africa, and Northeast Africa. They were especially close to other ancient groups from central and northern Sudan. Among the groups studied, the Kerma people were most similar to the Kush populations in Upper Nubia. They were also similar to the A-Group culture people of Lower Nubia and to Ethiopians.

Claude Rilly, citing anthropologist Christian Simon, says that the Kerma population had different physical types. He found three main groups. One group was similar to modern Kenyan skeletons. Another was similar to Middle Kingdom Egyptian skeletons from the Aswan region. The third group was distinct but shared features with the second. He notes that the first two groups were present in Early Kerma but became the majority later. The third group was mainly in early Kerma. It might represent the descendants of the Pre-Kerma people who founded Kerma.

S.O.Y. Keita did a study on skulls from North Africa, including Kerma (around 2000 BC) and early Egyptian pharaohs. The study found that many early Egyptian skulls were similar to "Southern" or "tropical African" types. These types had similarities with Kerma Kushites. The results generally show a closer link to groups from the Upper Nile Valley. But they also suggest changes from earlier skull patterns. This might be due to people moving and officials from the north going to important southern cities.

Images for kids

-

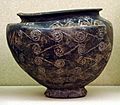

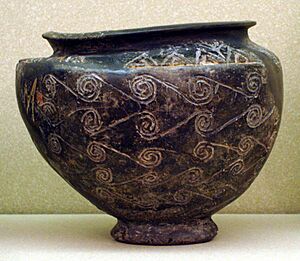

Ancient Kerma bowl kept at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. "Bowl with Running-Spiral Decoration".

See also

● Doukki Gel

- List of monarchs of Kerma

- Gash Group

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |