Kinetic art facts for kids

Kinetic art is a type of art that moves! It can be anything from a painting that seems to move as you look at it, to a sculpture with parts that actually spin or sway. The word "kinetic" comes from a Greek word meaning "of motion."

Today, when we talk about kinetic art, we usually mean 3D sculptures. These sculptures might move naturally, like with the wind, or they might be powered by a motor or even by you! Kinetic art uses many different ways to create movement.

Sometimes, kinetic art creates "virtual movement." This means the movement is only seen from certain angles. There's also "apparent movement," which happens when motors or electricity make the art move. These ideas are sometimes linked to "op art," which uses optical illusions to make you think things are moving.

The idea of kinetic art started to grow in the late 1800s. Artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Édouard Manet were Impressionists who tried to show movement in their paintings. They wanted their art to feel more alive. For example, Degas painted dancers and racehorses to capture a sense of "photographic realism."

By the early 1900s, artists really started focusing on dynamic motion. Naum Gabo was one of the artists who helped name this style. He talked about his work having "kinetic rhythm." His moving sculpture Kinetic Construction (1919–20) is seen as one of the first of its kind in the 20th century. From the 1920s to the 1960s, many artists explored kinetic art, creating mobiles and new kinds of sculptures.

Contents

How Kinetic Art Began

Artists worked hard to make their art feel less stiff and more alive. In the 19th century, Impressionist painters like Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, and Claude Monet started these changes. They each had their own ways of showing movement, but they all wanted their art to be more realistic.

Around the same time, the sculptor Auguste Rodin also explored movement in his early works. However, he later wondered if it was truly possible to capture a moment in time and make it feel as lively as real life in a solid sculpture.

Édouard Manet's Moving Art

Édouard Manet was an artist who didn't fit into just one art style. In his painting Le Ballet Espagnol (1862), he made the dancers' shapes and movements suggest depth. He also made the painting feel a bit unbalanced. This makes you feel like you're seeing a moment that's about to pass. The blurry colors and shadows also add to this feeling of a quick, fleeting moment.

Manet continued to explore movement in paintings like Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863). He used light, color, and how things were placed to create a sense of movement.

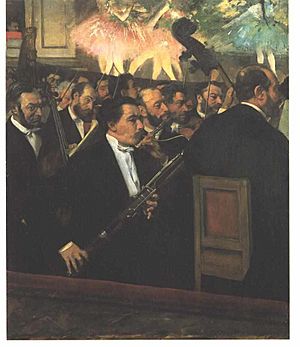

Edgar Degas and Dynamic Scenes

Edgar Degas was a very important Impressionist artist. He loved to paint ballet dancers and horse races because they were full of movement. He wanted to show "youth in movement."

In his work L’Orchestre de l’Opéra (1868), Degas puts the orchestra right in front of you, while the dancers are in the background. This makes the painting feel like it has many layers of movement. He continued this idea with his horse race paintings, like Voiture aux Courses (1872).

His painting Chevaux de Course (1884) really showed his skill. The horses and their owners look like they are caught in a real moment. People were surprised when they learned Degas used actual photographs to help him create these dynamic scenes.

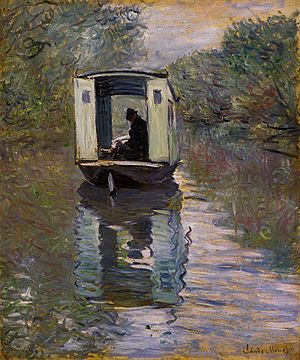

Claude Monet's Vibrating Brushstrokes

Claude Monet also used his "retinal impression" – what he saw directly – to create movement in his art. Like Degas, he was influenced by photography.

By 1875, Monet's painting style became very quick and fluid. In Le Bâteau-Atelier sur la Seine, the landscape seems to move with his brushstrokes, making the figures part of the motion. Paintings like Gare Saint-Lazare (1877-1878) showed how Monet was changing Impressionism. He combined color, light, and movement in new ways. His brushstrokes were so lively that his paintings seemed to have a "striking vibration."

Auguste Rodin's Sculptural Challenge

Auguste Rodin was initially impressed by Monet's "vibrating works" and Degas' way of showing space. He even wrote articles supporting this style, saying that their art captured life through movement.

However, when Rodin started sculpting his own art in 1881, he faced a challenge. How could he make solid sculptures show movement and drama? This made him rethink his ideas. He then argued that Impressionism wasn't about showing movement, but about presenting it in a still form.

Kinetic Art in the 20th Century

The Surrealist style of the 20th century helped lead to kinetic art. Artists felt free to explore new subjects and styles. With support from artists like Albert Gleizes, other modern artists like Jackson Pollock and Max Bill found new ways to create art that moved.

Albert Gleizes and Rhythm

Albert Gleizes was an important thinker in early 20th-century European art. His ideas about cubism made him very respected. He supported the idea of "rhythmic movement" in art. Gleizes believed that art should have rhythm, meaning that figures in a painting or sculpture should be placed in a way that makes them seem to interact and move together. He thought that figures should have somewhat unclear shapes so that viewers could imagine them moving within the space.

Jackson Pollock's Action Painting

Jackson Pollock became a leader in kinetic art in the 1950s with his unique style. His work is linked to "action painting," a term coined by art critic Harold Rosenberg. Pollock wanted every part of his paintings to feel alive. He often said, "I am in every painting." He used unusual tools like sticks and knives.

Pollock's famous "drip technique" involved flicking paint onto the canvas, creating squiggly lines and jagged strokes. He even used aluminum paint and made "splashes" to break up the material's usual look. He felt he was freeing art materials from their limits, which led to his moving, kinetic art.

Max Bill's Mathematical Movement

Max Bill was a strong supporter of the kinetic art movement in the 1930s. He believed that kinetic art should be based on mathematics. For him, using math was the best way to create objective movement. He used materials like bronze, marble, copper, and brass in his sculptures.

Bill also liked to play tricks on the viewer's eye. In his Construction with Suspended Cube (1935-1936), the mobile sculpture looks perfectly balanced from one angle, but from another, it appears uneven.

Mobiles and Sculptures That Move

Max Bill's sculptures were just the start of kinetic art that truly moved. Artists like Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, and Alexander Calder took still sculptures and gave them the ability to move. They first experimented with unpredictable movement, then tried to control it with technology. The term "mobile" describes art that can change based on gravity or air.

A mobile is usually not considered a mobile if the viewer can control its movement. When a piece only moves in special situations, or if the viewer controls it, that's called "virtual movement."

Kinetic art ideas have also influenced mosaic art. Kinetic mosaics often use strong contrasts between bright and dark tiles, and 3D shapes, to create the illusion of shadows and movement.

Vladimir Tatlin's Early Mobiles

Many experts believe Russian artist Vladimir Tatlin, who started the Russian Constructivism movement, created the first mobile sculpture. Even though the word "mobile" wasn't used until later, it fits Tatlin's work. His mobile, Contre-Reliefs Libérés Dans L'espace (1915), was a series of suspended parts that seemed to float freely in the air.

Tatlin's Tower, or the 'Monument to the Third International' (1919–20), was a design for a huge moving building that was never built. It was meant to be a headquarters and monument in Russia after the 1917 revolution.

Tatlin saw his art as a process that was always changing, not something with a clear beginning or end.

Alexander Rodchenko's Hanging Creations

Alexander Rodchenko, a friend of Tatlin, continued to study suspended mobiles. He developed a style called "non-objectivism." This style used objects with different materials and textures to make the viewer think new thoughts. By making the art feel a bit disconnected, it seemed like the figures were moving off the canvas. His painting Dance, an Objectless Composition (1915) shows this idea.

By the 1920s and 1930s, Rodchenko applied his ideas to mobiles. His 1920 piece Hanging Construction is a wooden mobile that hangs from the ceiling and spins naturally. It has circles that exist on different levels, and the whole sculpture rotates.

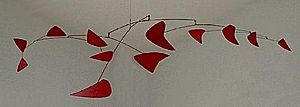

Alexander Calder: The Mobile Master

Alexander Calder is widely known for defining the style of mobiles in kinetic art. Some people think he was influenced by Chinese windbells or by Man Ray's mobiles from the 1920s, like Shade (1920).

Calder disagreed, saying his art was his own unique creation. However, his early mobile, Mobile (1938), did have some similarities to Man Ray's Shade. Both had a single string to hang them, and they both had crinkled parts that vibrated in the air.

Calder created two main types of mobiles that are now standard in kinetic art: object-mobiles and suspended mobiles. Object-mobiles stand on supports and can move in many ways. Suspended mobiles were first made with colored glass and small wooden objects hanging on long threads.

While his earliest object-mobiles might not seem very "kinetic," by the 1960s, Calder had perfected them. In his Cat Mobile (1966), the cat's head and tail move randomly, but its body stays still. Calder didn't invent suspended mobiles, but he became famous for his original designs.

His McCausland Mobile (1933) was different because of its unusual shapes, which other artists might not have thought were good for mobiles. Calder used mathematical relationships to balance his mobiles, but his formulas changed for each new piece, making them hard to copy.

Virtual Movement in Art

By the 1940s, new types of mobiles, sculptures, and paintings started to let the viewer control the movement. Artists like Calder, Tatlin, and Rodchenko continued their work, but new artists like Victor Vasarely introduced "virtual movement." This new style faced some criticism at first.

Interactive Art with Electricity

Victor Vasarely created many interactive artworks in the 1940s. One of his pieces, Gordes/Cristal (1946), was a series of cubic shapes powered by electricity. At art shows, he invited people to press a switch to start a light and color show. Virtual movement is a type of kinetic art that can be linked to mobiles, but it also led to other specific kinds of kinetic art.

Apparent Movement and Op Art

"Apparent movement" describes kinetic art that moves on its own, without the viewer's help. This includes everything from Pollock's drip paintings to Tatlin's first mobile. By the 1960s, the term "op art" was used for optical illusions and art that tricked the eye on flat surfaces. Op art sometimes overlaps with kinetic art, especially with stationary mobiles that create optical effects.

In 1955, artists like Victor Vasarely and Pontus Hulten promoted new kinetic art ideas based on light and optical illusions. The term "kinetic art" in its modern sense first appeared in Zurich in 1960. It really grew in the 1960s, including both optical art (like Bridget Riley's work) and art based on actual movement (like Yacov Agam or Jesús Rafael Soto).

From 1961 to 1968, a group called GRAV (Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel) was formed by artists like François Morellet and Julio Le Parc. They wanted the public to directly participate in their art, often using interactive mazes.

Kinetic Art Today

In November 2013, the MIT Museum opened an exhibition called 5000 Moving Parts. It showed kinetic art by artists like Arthur Ganson and Rafael Lozano-Hemmer. This exhibition started a "year of kinetic art" at the museum.

"Neo-kinetic" art is also popular in China. You can find interactive moving sculptures in many public places, like Wuhu International Sculpture Park and in Beijing.

Singapore Changi Airport in Singapore has a collection of artworks, including large kinetic installations by international artists ART+COM and Christian Moeller.

Selected Works

-

Lyman Whitaker, The Twister Star Huge, a whirligig sculpture.

-

Jesús Raphael Soto, La Esfera, Caracas, Venezuela.

-

David Ascalon, Wings to the Heavens, 2008.

-

Wave, Park West, by Angela Conner.

-

Nicolas Schoeffer Chronos 10B, 1980, Munich.

-

Yaacov Agam, Sheba Medical Center, Israel.

-

Marc van den Broek, Sun Writer, 1986, Germany.

-

Turpin + Crawford Studio, Halo, Sydney, Australia.

-

George Rhoads, Archimedean Excogitation (1987), a rolling ball sculpture, Museum of Science, Boston, United States.

Famous Kinetic Sculptors

- Yaacov Agam

- Uli Aschenborn

- David Ascalon

- Fletcher Benton

- Mark Bischof

- Daniel Buren

- Alexander Calder

- Gregorio Vardanega

- Martha Boto

- U-Ram Choe

- Angela Conner

- Carlos Cruz-Diez

- Marcel Duchamp

- Lin Emery

- Rowland Emett

- Arthur Ganson

- Nemo Gould

- Gerhard von Graevenitz

- Bruce Gray

- Ralfonso Gschwend

- Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

- Chuck Hoberman

- Anthony Howe

- Irma Hünerfauth

- Tim Hunkin

- Theo Jansen

- Ned Kahn

- Roger Katan

- Starr Kempf

- Frederick Kiesler

- Viacheslav Koleichuk

- Gyula Kosice

- Gilles Larrain

- Julio Le Parc

- Liliane Lijn

- Len Lye

- Sal Maccarone

- Heinz Mack

- Phyllis Mark

- László Moholy-Nagy

- Alejandro Otero

- Robert Perless

- Otto Piene

- George Rickey

- Ken Rinaldo

- Barton Rubenstein

- Nicolas Schöffer

- Eusebio Sempere

- Jesús Rafael Soto

- Mark di Suvero

- Takis

- Jean Tinguely

- Wen-Ying Tsai

- Marc van den Broek

- Panayiotis Vassilakis

- Willem van Weeghel

- Lyman Whitaker

- Ludwig Wilding

Famous Kinetic Op Artists

- Nadir Afonso

- Getulio Alviani

- Marina Apollonio

- Carlos Cruz-Díez

- Ronald Mallory

- Youri Messen-Jaschin

- Vera Molnár

- Abraham Palatnik

- Bridget Riley

- Eusebio Sempere

- Grazia Varisco

- Victor Vasarely

- Jean-Pierre Yvaral

- Romano Rizzato

See also

In Spanish: Arte cinético para niños

In Spanish: Arte cinético para niños

- Barrier-grid animation § Kinegram

- Gas sculpture

- Lumino kinetic art

- Odonien

- Robotic art

- Sound art

- Sound installation