Kunio Kishida facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

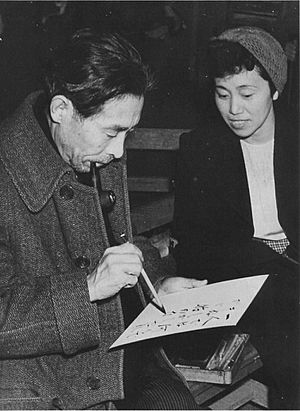

Kishida Kunio

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Native name |

岸田國士

|

| Born | November 2, 1890 Yotsuya, Tokyo |

| Died | March 5, 1954 (aged 63) Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation | playwright, novelist, critic, translator, impresario, lecturer |

| Language | Japanese |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Alma mater | Meiji University, University of Tokyo |

| Period | 1923 - 1954 |

| Genre | Shingeki |

| Spouse | Murakawa Tokiko |

| Children | 2 |

Kunio Kishida (岸田 國士, Kishida Kunio, born November 2, 1890 – died March 5, 1954) was a very important Japanese playwright, novelist, and critic. He was a big supporter of "Shingeki" (which means "New Theatre" or "New Drama") in Japan.

Kishida helped change Japanese theatre by making plays and acting styles more modern. He strongly believed that theatre should be a serious place for both art and literature. Before Kishida, many people tried to modernize Japanese theatre, but he was the first to truly succeed. He changed how stories were told, what themes were explored, and how actors performed.

Kishida was not a fan of traditional Japanese theatre like kabuki, noh, and shimpa. After living in France for a while, he was very inspired by European plays and acting. He thought these new ideas should be used in Japanese theatre. While he didn't want Japan's theatre to become completely Western, he knew Japan needed to adapt as it became more connected to the world. For Kishida, theatre was not just for fun entertainment. He saw it as a deep and important way to express creativity.

Contents

- Growing Up and School (1890–1919)

- Discovering European Theatre (1919 – 1923)

- Back in Japan and Early Theatre Changes (1923 – 1929)

- Theatre Groups and New Ideas (1926 – 1936)

- The Literary Theatre (1937 – 1954)

- Theatre Criticism

- Kishida's Thoughts on Japanese Theatre

- Kishida and Shingeki

- Personal Life

- Death

- Play Style and Themes

- Legacy

- Influences

- Directing Work

- Film Adaptations

Growing Up and School (1890–1919)

Kishida was born on November 2, 1890, in Yotsuya, Tokyo. His family had a military background with old samurai roots. His father, Shozo, was an officer in the Imperial Army, and it was expected that Kishida would follow in his footsteps.

When he was young, Kishida went to military schools. At age seventeen, he discovered a love for literature, especially French writers like François-René de Chateaubriand and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

He joined the Japanese military in 1912 as an officer, following his family's tradition. However, Kishida left the military in 1914 because he didn't enjoy that career. After leaving the army, Kishida decided to follow his passion for literature. He enrolled in Tokyo Imperial University in 1917. There, he studied French language and literature.

Discovering European Theatre (1919 – 1923)

In 1919, Kishida traveled to France to learn about European theatre and explore his literary interests. He worked as a translator at the Japanese Embassy in Paris and for the League of Nations. This helped him afford to live in France for several years.

Soon after, Kishida studied theatre at the Theatre du Vieux-Colombier. This was the start of his lifelong love for French drama. His teacher, Jacques Copeau, taught him about the history and customs of French and European theatre. Kishida also watched many European plays. He learned a lot about what made Western plays successful. He especially noticed how actors could show subtle emotions and speak naturally, without sounding fake.

Modern European acting became very effective because of the Drama Purification Movement. This movement wanted to remove anything artificial from theatre. Copeau strongly supported this idea and trained his actors to perform in an open and natural way. Kishida realized this natural acting style was missing in Japanese theatre like kabuki, noh, and shimpa.

Besides French theatre, Kishida loved other European playwrights. He saw Copeau's plays by Henrik Ibsen, Anton Chekhov, and August Strindberg. He admired their plays because the characters and stories had deep psychological and emotional meaning.

While studying with Copeau in 1921–1922, Kishida wrote his first play, A Wan Smile. He was inspired after hearing a famous Russian actor, Georges Pitoëff, say he wanted to perform a Japanese play. Kishida had Japanese plays to share, but he decided to write his own instead. Pitoeff said Kishida's play was "really quite interesting," but it's not known if it was ever performed.

In October 1922, Kishida took a break and moved to Southern France to recover from a serious lung illness.

Back in Japan and Early Theatre Changes (1923 – 1929)

Kishida quickly returned to Japan in 1923 after his father passed away. He needed to care for his mother and sisters. His recent illness, leaving Europe suddenly, and his sadness made him unsure about his future career.

Kishida became interested in the plays of Yuzo Yamamoto, a modern writer. A friend introduced them, and Kishida shared his play A Wan Smile with Yamamoto. Kishida worried Yamamoto, who loved German literature, might not like his French-influenced play. But after reading it, Yamamoto praised the play for being very original compared to other Japanese plays at the time.

Feeling more confident, Kishida wanted to write plays again. However, the Great 1923 Kanto Earthquake badly damaged Tokyo, destroying most of the city's theatres. To earn money, Kishida opened a French language school called The Moliere School, named after the famous 17th-century playwright.

Yamamoto helped Kishida start his playwriting career by creating a theatre magazine called Engeki Shincho (New Currents of Drama). This magazine aimed to show the latest in Japanese theatre. Kishida's play A Wan Smile (renamed Old Toys) was published in the magazine's March 1924 issue.

Because of his wide knowledge of French and European theatre, Kishida started writing essays and reviews for many theatre journals and magazines. These included Bungei Shunju (Literary Annals) and Bungei Jidai (Literary Age). Along with his playwriting, Kishida quickly became a very important person in Japanese drama.

The Tsukiji Little Theatre opened in Tokyo in 1924. It was a big change for Japanese theatre because it focused on new, European plays instead of kabuki and noh. Kishida was asked to review the Tsukiji's opening night plays. He went with an open mind to see how these plays fit current Japanese drama trends. He knew the theatre director, Kaoru Osanai, had made a bold choice to only stage Western plays. Kishida hoped to work with Osanai, using his knowledge of European theatre to help with the Tsukiji's productions. The opening night featured Japanese versions of Chekhov's Swan Song, Emile Mazaud's The Holiday, and Reinhard Goering's A Sea Battle.

Even though he admired European theatre, Kishida wrote a very harsh review of the performances and Osanai's leadership. He said the acting was weak and criticized the theatre for spending too much on stage designs instead of actor training. He felt the Japanese versions of these non-Japanese plays were poorly done and hard for the audience to understand. The worst part of his review was a section where he called Osanai "pretentious and dogmatic." This review caused a lot of conflict between Kishida and Osanai. Osanai then decided never to stage any of Kishida's plays at the Tsukiji Little Theatre.

The Tsukiji's opening night showed Kishida's bigger unhappiness with Japanese theatre. He felt traditional kabuki and noh were old-fashioned, and Japanese attempts at Western drama were just copies. With his knowledge and inspiration from Europe, Kishida felt it was vital for Japanese theatre to tell more serious, psychological stories and improve actors' skills. For the rest of the 1920s, Kishida focused on writing plays that matched his vision for Japan. These were often one-act stories with only a few characters, usually set in private homes. The stories focused on relationships and personal issues, avoiding social or political themes. This became a key feature of Kishida's plays.

Theatre Groups and New Ideas (1926 – 1936)

To modernize Japanese theatre, Kishida started the New Theatre Institute (Shingeki kenkyusho) in 1926. With playwrights Iwata Toyoo and Sekiguchi Jiro, this was an experimental school. It aimed to teach young writers and actors new ways to create and perform theatre. However, students didn't fully understand the lessons, partly because the Institute lacked resources. Unlike Copeau, Kishida didn't have many experienced guest lecturers. Also, there weren't many skilled Western-style performances in Japan, making it hard for students to practice what they learned. Kishida tried to fix this by showing foreign film versions of Western plays, but it wasn't enough.

Even though the Institute didn't meet Kishida's hopes, he found a loyal student, Tanaka Chikao. Tanaka joined in 1927 and was praised for his deep understanding of French literature, especially French plays and dialogue.

As Kishida became more famous in theatre, he founded the Tsukiji Theatre (Tsukijiza) in 1932. Working with actors Tomoda Kyosuke and Tamura Akiko, this theatre was Kishida's first place to stage plays based on Western theatre ideas. Kishida wanted to stage Western plays, like Osanai, but he didn't want actors whose style came from the emotional way of kabuki. The Tsukiji Theatre didn't attract enough people because other theatre groups became very popular at the same time. Groups like the New Associated Drama Troupe (Shinkyo Gekidan) and The New Tsukiji Drama Troupe (Shin-Tsukiji Gekidan) became more famous. The theatre closed in 1936, but Kishida quickly moved to a more popular place, the Bungakuza.

The Literary Theatre (1937 – 1954)

In 1937, Kishida helped start The Literary Theatre (Bungakuza) with Iwata Toyoo and Michio Kato. This theatre was a place to stage Western plays. While similar to Osanai's theatre, Kishida chose plays that focused on personal and individual themes, not social or political ones.

Kishida's knowledge of French drama greatly influenced the theatre's choice of famous playwrights. These included Roger Martin du Gard, Jules Romains, Jean-Victor Pellerian, Simon Gantillon, and Marcel Pagnol.

In 1938, the Japanese government sent Kishida to China to write about the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. The government saw him as a "safe" writer because his plays were thoughtful and not political. Kishida wrote about his travels in China in his book Jugun gojunichi (Following the Troops for Fifty Days).

However, Kishida's reputation suffered during World War II. Since his plays didn't have political messages, he was one of the few playwrights whose work was not censored by the government. Other theatre groups with political, anti-Fascist views were shut down, and their members arrested. Kishida became less popular because he joined the Imperial Rule Assistance Association (Taisei Yokusankai). This government-backed group required its members to follow state policies. For Kishida, this meant continuing to stage plays that were politically neutral and didn't criticize the government.

During the Occupation of Japan in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Kishida's new interest in modern American plays helped ease tensions between Japan and the American military. Soldiers preferred shingeki theatre because its performances, stories, and settings were more Western. Plays like Tennessee Williams's A Streetcar Named Desire and Thornton Wilder's Our Town were staged. Kishida's reputation for directing plays that were mostly not political helped keep things calm. American forces didn't like kabuki and noh because they focused too much on Japanese culture and history, and they worried these plays might restart strong national feelings.

While Western plays were very popular at The Literary Theatre, Kishida didn't only stage Western works like Osanai did. He also produced Japanese plays, as long as they had no political messages. For example, Kaoru Morimoto's Surging Waves was performed in October 1943, and The Life of a Woman in April 1945. These performances helped Kishida regain his good name among the Japanese people after 1945.

By the 1950s, Kishida and The Literary Theatre often encouraged younger, unknown playwrights to have their plays performed. This openness helped start the careers of many playwrights from the late 20th and early 21st centuries. These included Kishida's student Tanaka Chikao, Yukio Mishima, and Michio Kato.

Theatre Criticism

Besides being a playwright and director, Kishida helped modernize Japanese drama through the many essays and reviews he published. These appeared in theatre journals and magazines like Bungei Shunju (Literary Annals) and Bungei Jidai (Literary Age).

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Kishida started several new theatre publications. He used these to share articles, essays, and reviews about changes in Japanese drama. Examples include Tragedy and Comedy in 1928 and Gekisaku (Play Writing) in 1932.

Kishida's Thoughts on Japanese Theatre

Throughout his life, Kishida believed traditional Japanese theatre was old-fashioned and not as good as Western drama. He openly disliked kabuki for its melodrama and focus on big, exaggerated emotions instead of subtle, natural ones. He also disliked shimpa because it tried to show modern life but still kept the emotional style of kabuki.

While he wasn't a fan of noh, Kishida didn't criticize it as much as kabuki and shimpa. He thought noh was so different from modern Japanese drama that it was its own separate thing and wouldn't get in the way of changing Japanese theatre.

Kishida once wrote about a kabuki performance he saw after returning to Japan in 1923. Even though he described it as a powerful and joyful experience, he still felt that Japanese theatre needed to modernize. He argued that traditional theatre was too tied to the past and couldn't look to the future at the same time.

Kishida and Shingeki

Even though Kishida had many issues with Japanese drama, he made it clear he didn't want Japan to lose its identity and become completely Western. However, he noted that European theatre history is full of different countries influencing each other's plays and acting styles, calling it "an amalgamation."

Starting in the 1920s, Kishida developed his idea for Shingeki ("New Drama/New Theatre") as the best way to modernize Japanese theatre. Influenced by European ideas like Naturalism and Symbolism, these plays aimed to use Western theatre customs. This meant natural acting and stories with deep psychological meaning. As both an observer and a director, Kishida said theatres needed to understand the important connection between the playwright, stage, director, actors, and audience.

Kishida chose to write and feature plays about middle and upper-class characters. This showed his preference for educated audiences.

Personal Life

In 1927, Kishida married Murakawa Tokiko. They had two daughters. After Tokiko passed away in 1942, friends of Kishida said he never fully recovered from her death.

Both of Kishida's daughters became involved in the arts. Eriko (1929–2011) was a poet and wrote children's stories. Kyoko (1930–2006) was an actress who first performed in 1950.

Death

Kishida died from a stroke in Tokyo on March 5, 1954. He was at a dress rehearsal for a play he was involved with.

Play Style and Themes

Style

Kishida wrote over 60 plays, including dramas and funny satires. His early plays, like Old Toys, were short, one-act stories with only a few characters. These were often called "sketch plays." A famous short play is Paper Balloon (1925), about a married couple playfully imagining how they would spend a Sunday.

Later, his stories became more complex, with many acts and different storylines involving several characters. Ushiyama Hotel (1928) is set in a Japanese hotel in Haiphong, Vietnam. It's the main place where different guests and workers get involved in each other's personal lives.

When writing scripts, Kishida believed dialogue was very important. He thought it should drive the story and help characters grow. He also felt it needed to be made of beautiful, literary words.

Content

Most of his plays focused on personal, emotional, and psychological issues of individual characters and their relationships. These stories usually took place in the homes of middle and upper-class people. For example, Mr. Sawa's Two Daughters (1935) is about the tense relationship between a government worker and his two adult daughters. It deals with family secrets and not taking responsibility for emotions.

While he wasn't very interested in plays about working-class people, a few of Kishida's plays did feature main characters from lower social classes. Examples include Roof Garden (1926) and Mount Asama (1931).

Themes

Kishida was different from other writers of his time because his plays usually didn't have social or political themes. This was notable because he wrote during times of political unrest and international conflict.

Some of the most common themes in Kishida's work include space, time, memory, marriage, and irresponsibility.

Legacy

Kishida's efforts to modernize Japanese theatre were a slow and difficult process. His changes truly blossomed after his death in 1954. His new way of writing plays and acting styles developed throughout his life and are still important in Japanese drama today.

Copeau's directing style and the influential Drama Purification Movement inspired Kishida to bring natural and rhythmic dialogue to Japanese actors. His choice to have characters speak in simple, everyday phrases helped actors and playwrights move away from using fancy language that might confuse some audiences.

Kishida believed theatre was a creative space for both literature and art. This allowed him to use ideas from Western theatre to create more complex stories and characters with varied emotions.

As a theatre director and manager of The Literary Theatre, Kishida introduced Japanese audiences to many European and American playwrights. These included Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Jean Giraudoux, Jean Anouilh, Eugene Ionesco, Tennessee Williams, Anton Chekhov, Edmond Rostand, William Shakespeare, Thornton Wilder, and Eugene O'Neill.

The Literary Theatre still operates in Tokyo today. However, it no longer follows Kishida's strict rule of only staging politically neutral plays.

Kishida's willingness to give modern Japanese playwrights a chance to have their plays performed helped launch the careers of many diverse writers. These include Tanaka Chikao, Yushi Koyama, Kaoru Morimoto, Yukio Mishima, and Sawako Ariyoshi.

Since 1955, the annual Kishida Kunio Drama Award has been given by the Hakusuisha publishing house. It honors new playwrights who show a talent for groundbreaking theatre. It is considered Japan's most important award for playwriting.

Influences

Most of Kishida's inspiration came from his studies of European playwrights and directors. These included Jacques Copeau, Moliere, Jules Renard, William Shakespeare, Maurice Maeterlinck, Anton Chekhov, Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, and Charles Vildrac.

Despite his criticisms of Japanese theatre, Kishida named three Japanese playwrights from the Taisho Era who he believed greatly helped modernize Japanese drama:

- Kikuchi Kan for his focus on themes.

- Yuzo Yamamoto for his skill in plot structure.

- Mantaro Kubota for his literary writing style.

Directing Work

Kishida directed many plays throughout his career. Some of his notable directing credits include:

- 1926: Wire-Tapping by Kaneko Yobun

- 1927: Hazakura (The Cherry Tree in Leaf), by Kunio Kishida

- 1927: La paix chez soi (Peace at Home) by Georges Corteline

- 1932: La paix chez soi (Peace at Home) by Georges Corteline

- 1938: La paix chez soi (Peace at Home) by Georges Corteline

- 1938: Monsieur Badin

- 1938: Fish Tribe by Yushi Koyama

- 1938: Akimizumine by Naoya Uchimura

- 1940: Gears by Naoya Uchimura

- 1948: Woman Who Eats Dreams by Akira Nogami

- 1950: Doen Karan by Kunio Kishida

- 1954: The Lower Depths by Maxim Gorky

Film Adaptations

Some of Kishida's works were made into films:

- The Good Fairy (善魔, Zenma) (1951), directed by Keisuke Kinoshita, was based on his novel Zenma.

- Sudden Rain (驟雨, Shūu) (1956), directed by Mikio Naruse, was based on his play Shower.