L'Arbre Croche facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

L'Arbre Croche

Waganagisi

|

|

|---|---|

|

Region

|

|

| Etymology: crooked tree | |

| Country | United States |

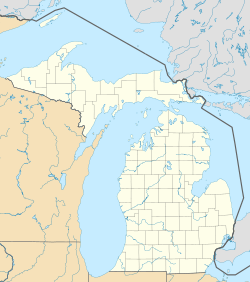

| State | Michigan |

| County | Emmet County |

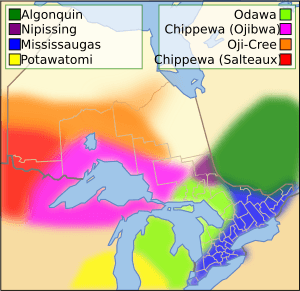

L'Arbre Croche, also called Waganagisi by the Odawa people, was a large Odawa settlement in Northern Michigan. The French named it L'Arbre Croche, meaning "the crooked tree." This name came from a large, bent tree that was easy to see from far away and marked the center of the settlement. The area stretched from Harbor Springs to Cross Village in what is now Emmet County, Michigan.

The Odawa people moved to the L'Arbre Croche area in 1741 with Jesuit missionaries. For many years, the Odawa community worked closely with French, British, and American groups. These groups were often at nearby trading posts and forts like Fort Michilimackinac and Fort Mackinac. The Odawa provided furs, canoes, and food for the fur trade. They had a special connection with the French, who built missions and churches in the community.

During the 1750s and 1760s, a smallpox outbreak greatly affected many Native American communities. An oral story from Odawa leader Andrew Blackbird said that L'Arbre Croche was "entirely depopulated" by this disease. After the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the French left the region. The British then took control of Fort Michilimackinac.

Nissowaquet, an Odawa leader, and his warriors supported the British during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783). They took part in several military trips. Later, when the area became part of the Michigan Territory (1805–1837), Native Americans lost much of their land. In 1836, the Odawa gave up land across large parts of Michigan when they signed the Treaty of Washington. Chief Joseph Nowimashkote then started a plan for the Odawa to buy back their land at Cross Village. The village of Harbor Springs became an important center for the L'Arbre Croche community in the early 1800s. It had a church, a school, and the country's first temperance society.

Today, L'Arbre Croche is also known as a Catholic community with four churches. One of these is the St. Ignatius Church in Middle Village.

Contents

What Does L'Arbre Croche Mean?

The name L'Arbre Croche means "the crooked tree" in French. The bent top of a large pine tree was a famous landmark for people traveling on Lake Michigan. This tree is no longer standing. It was located near Middle Village, about 20 miles (32 km) north of Harbor Springs. The Odawa name for the community was Waganagisi, which also means "bent tree."

Early History of L'Arbre Croche

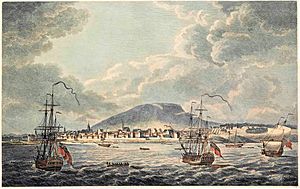

The French had a fur trading post at Michilimackinac in what is now Michigan. The Odawa people in the area traded animal furs with the French. A Jesuit missionary named Jacques Marquette (1637–1675) started the St. Ignace Mission at Michilimackinac in the late 1600s. Pierre du Jaunay, a French Jesuit priest, worked as a missionary at Michilimackinac starting in 1735. He served the French, British, Native Americans, and traders for nearly 30 years from the Sainte-Anne log church. Nissowaquet was one of the Odawa leaders who lived near Fort Michilimackinac.

In 1740, the Odawa decided they needed to move to land that was better for farming. The leader of Fort Michilimackinac, Pierre Joseph Céloron de Blainville, took the Odawa chiefs to Quebec. There, they met with the Marquis de Beauharnois, who offered them several places to settle. With Father Du Jaunay's help, the Odawa chose the nearby area known as L'Arbre Croche.

Life in L'Arbre Croche

New France Era (1534–1763)

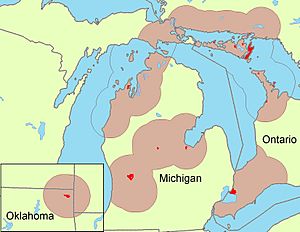

In the summer of 1741, the Odawa, including Nissowaquet and about 180 warriors, moved to L'Arbre Croche with the Jesuits. They started a mission called Apatawaaing. L'Arbre Croche, also known as Waganagisi, was the largest settlement in the Great Lakes region at that time. It covered much of what is now Emmet County, Michigan. There were many villages along the shoreline from Fort Michilimackinac down to Little Traverse Bay. Beauharnois sent French men from Michilimackinac to help the Odawa prepare the soil for farming. A church was built at Cross Village in 1742. Father Du Jaunay divided his time between the Sainte-Anne church and the Saint-Ignace mission in Cross Village, where he also had a farm. He was helped by other French priests.

The Odawa people of L'Arbre Croche fished, hunted, and grew their own food. They grew corn, squash, onions, cucumbers, turnips, cabbages, and melons. They also gathered wild strawberries. The Odawa traded with the French at Mackinac Island, which was a major fur-trading center. They traded food, bark, and canoes for items like clothing, glass, and porcelain beads. The canoes and food, including dried fish, meat, and produce, were important for fur traders working in the Great Lakes and Upper Mississippi regions. In the fall, the Odawa moved south to rivers like the St. Joseph River. There, families would hunt for furs. In the spring, they made maple sugar and then returned to L'Arbre Croche.

British Rule (1763–1787)

Ojibwa warriors from Michilimackinac attacked the British fort (Treaty of Paris (1763)) in June 1763. They were led by Minweweh, who was very loyal to the French. The traders and soldiers who survived were saved by Nissowaquet's warriors and taken to L'Arbre Croche. They were protected there for a month. Nissowaquet was given gifts and trade goods for his help. Some of these goods were used to free captives from the Ojibwa. Nissowaquet then took the refugees from the fort to the British in Montreal. He promised to have a good relationship with the British, just as he had with the French. However, the British and American governments did not support the mission and would not pay for a priest after Father Du Jaunay left in 1765.

From the 1750s to the 1760s, a smallpox outbreak severely affected many Native American communities in the American Midwest. This included L'Arbre Croche. The Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples were most impacted. An oral story from Odawa leader Andrew Blackbird said that the outbreak had "entirely depopulated and laid waste" to L'Arbre Croche. Blackbird's story claimed that a group of Odawa were sold a tin box in Montreal. They were told it held something special but not to open it until they were home. The box supposedly contained smaller boxes, with the final tiny box holding moldy particles that caused smallpox. According to this story, entire families in L'Arbre Croche died, and the population was greatly reduced.

Nissowaquet supported the British during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783). He and his warriors joined several expeditions.

Northwest Territory (1787–1803)

The Odawa and Ojibwa from northern Michigan fought alongside other Native Americans against the United States government. This happened at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. The Native peoples fought to protect their traditional lands from settlers moving west. After losing the battle, Mackinac Island became part of the United States, as agreed in the Treaty of Greenville.

In 1799, Father Gabriel Richard, a Catholic missionary from Detroit, visited the Odawa at L'Arbre Croche. Soon after, another smallpox outbreak spread through the Great Lakes region. More than half of the people in L'Arbre Croche died.

Michigan Territory (1805–1837)

In 1807, an Odawa warrior named Le Maigouis, or The Trout, traveled from L'Arbre Croche to Tenskwatawa's village in Ohio. Tenskwatawa, also called the Shawnee Prophet, had started a new religion. Trout wanted to learn more about it. When Trout returned to Michigan, he successfully shared this religion with the Odawa and Ojibwa of L'Arbre Croche and the northern part of Michigan. The prophet wanted to bring "spiritual salvation and cultural renewal." He taught people to return to traditional ways, like caring for widows and respecting elders. He also told them to give up white people's ways, such as using alcohol, firearms, and European cooking tools. Another message was to hunt only the animals needed for the tribe, not for white fur traders. This would help animal populations grow again. The prophet's brother, Tecumseh, helped spread this religion across the Great Lakes region.

By September 1807, the Odawa had stopped buying alcohol at Michilimackinac. Alcohol had been a very profitable product for traders. Traders tried to get people to buy it again by giving away many gallons, but no one took it. In 1808, some of the new followers moved to Tenskwatawa's village, Prophetstown, in what is now northwest Indiana. However, the settlement could not support so many people. There wasn't enough farmland, and the prophet did not allow trading for food with white people. As people starved, they had to eat their horses and then their dogs. More than 100 people from L'Arbre Croche died, and the remaining, disappointed people returned home.

In 1819, L'Arbre Croche was a group of ten villages with about 1500 people. By 1820, between 1,000 and 1,200 Odawa lived in the Little Traverse Bay area of L'Arbre Croche. They lived in groups of lodges along the bay's shore.

In 1825, the United States government provided money for a Catholic priest. A log chapel, named St. Vincent, was built in 1825. At that time, there were about 1,500 Odawa at L'Arbre Croche. Father Frederic Baraga came to Cross Village in 1831. He is known for creating an Odawa language alphabet and dictionary. He also started many churches in the area. Bishop Baraga was later replaced by another Slovenian missionary priest, Father Francis Xavier Pierz.

Native Americans in Michigan Territory (1805–1837) lost much of their land in the early 1800s. In 1836, the Odawa gave up land across most of Michigan when they signed the Treaty of Washington. Chief Joseph Nowimashkote started a plan for the Odawa to buy back their land at Cross Village. The village of Harbor Springs was created with a church, a house for the minister, a school, and the country's first temperance society. At that time, L'Arbre Croche was part of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cincinnati.

A historical marker for L'Arbre Croche is located on the Tunnel of Trees Scenic Heritage Route on Michigan State Highway 119.

Notable People from L'Arbre Croche

- Andrew Blackbird - An Odawa tribal leader and historian.

- Elizabeth Bertrand - A notable person connected to the community.

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |