Letters to the inhabitants of Canada facts for kids

The Letters to the inhabitants of Canada were three important messages. They were written by the American Continental Congress in 1774, 1775, and 1776. These letters were sent to the people living in the Province of Quebec. This area used to be the French province of Canada. At that time, Quebec did not have a system where people could elect their own leaders.

The main goal of these letters was to convince the many French-speaking people in Quebec to join the American fight for independence. However, this plan did not work. Quebec and other northern British areas stayed loyal to Britain. The only real help the Americans got was about 1,000 men who joined two regiments.

Contents

Why the Letters Were Sent: The Background

After the French and Indian War (1754–1763), Great Britain took control of the Province of Quebec. This meant Britain now controlled almost all the eastern coast of North America. The former French colony of Canada became much closer to the American colonies.

Quebec was very different from other British areas in North America. Most people in Quebec spoke only French and were Roman Catholic. Their laws were also based on French law, not British law.

In 1774, the British Parliament passed a law called the Quebec Act. This law was part of what American colonists called the Intolerable Acts. The Quebec Act replaced an older law and helped make Britain's power stronger in Quebec. It guaranteed that French Canadians could practice their Roman Catholic religion.

Historians believe this act was meant to stop French Canadians from joining the independence movement in the American colonies. However, American colonists saw it differently. They worried that allowing Catholicism in Quebec might lead to it being introduced everywhere. They also thought the new government structure in Quebec was Britain trying to control the province more and take away basic rights from its people.

The First Letter to Quebec

How the First Letter Was Written

On October 21, 1774, the First Continental Congress met. They were trying to decide how to respond to the Intolerable Acts. They decided to write letters to the people of Quebec, St. John's Island, Nova Scotia, Georgia, East Florida and West Florida. These colonies did not have representatives in the Congress.

A group of people, including Thomas Cushing, Richard Henry Lee, and John Dickinson, were chosen to write these letters. A first draft was shown on October 24, but it was sent back for changes. On October 26, a new draft was approved. The Congress decided that their president should sign the letter. They also ordered that the "Letter to the Inhabitants of the Province of Quebec" be translated into French and printed.

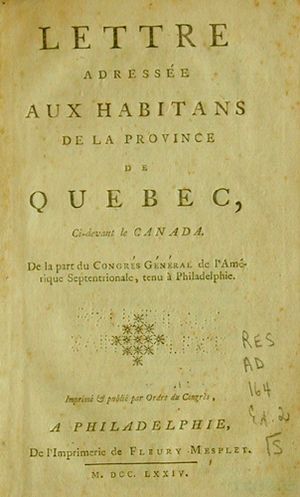

The letter was translated into French by Pierre Eugene du Simitiere. It was printed as an 18-page booklet. The final words of the letter are believed to have been written by John Dickinson.

What the First Letter Said

The letter told the people of Quebec about five important rights in British law. These rights were not being used in Quebec, even though it had been over ten years since the peace treaty of 1763. That treaty ended the French and Indian War. It made all French subjects in Canada new British subjects, supposedly with the same rights as other British people.

The five rights mentioned were:

- Representative government: where people elect their leaders.

- Trial by jury: where a group of citizens decides if someone is guilty.

- Habeas Corpus: a right to know why you are being held in prison.

- Land ownership: the right to own land.

- Freedom of the press: the right to publish news and ideas without government control.

The letter included quotes from famous thinkers like Beccaria and Montesquieu. Historian Marcel Trudel called this first letter "a crash course on democratic government." Another historian, Gustave Lanctôt, said it "introduced [among the inhabitants] the notion of personal liberty and political equality." He called it their first "political alphabet" and "first lesson in constitutional law."

The letter asked the people of Quebec to create their own local government. It also invited them to send representatives to the next Continental Congress. This meeting was planned for May 10, 1775, in Philadelphia.

How the First Letter Was Received

A French printer in Philadelphia, Fleury Mesplet, printed 2,000 copies of the French letter. Other handwritten French translations also circulated. Some might have even reached Canada before the official version.

However, General Guy Carleton, the Governor of Quebec, tried to stop the letter from being widely shared. But he reported to England that "letters of importance had been received from the General Congress" in Montreal. He also noted that town meetings were happening, showing the same spirit as the neighboring American colonies. These meetings, mostly led by English-speakers, did not result in delegates being chosen for the Continental Congress.

In early 1775, Boston's Committee of Correspondence sent John Brown to Quebec. His job was to gather information, see how people felt, and encourage rebellion. Brown found that English-speaking people had mixed feelings. Some worried that the Congress's plan to stop exports would hurt their fur trade. Most French-speaking people were neutral about British rule. Some were happy, but many could be convinced to help the Americans. Brown also noticed that there were not many soldiers in the province. Governor Carleton knew about Brown's actions but did not stop him, except by preventing the letter from being printed in the local newspaper.

The Second Letter to Quebec

Writing the Second Letter

The Second Continental Congress met on May 10, 1775. This was after the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19. In these battles, colonial forces fought against a large British army and pushed them back to Boston. This victory made the Congress feel very excited and hopeful.

John Brown arrived in Philadelphia on May 17. He reported that Fort Ticonderoga had been captured and Fort Saint-Jean had been raided. This news led to much discussion in Congress. On May 26, Congress decided to write a second letter to the people of Canada.

The committee chosen to write this letter included John Jay, Silas Deane, and Samuel Adams. Samuel Adams had already written a letter to Canada for the Boston Committee of Correspondence. On May 29, after hearing more about the situation in Montreal, the Second Continental Congress approved the letter.

The letter was called "Letter to the oppressed inhabitants of Canada." It was translated into French and signed by President John Hancock. Pierre Eugène du Simitière translated it again, and 1,000 copies were printed. The words of this letter are believed to have been written by John Jay.

What the Second Letter Said

In this letter, Congress again criticized the government set up by the Quebec Act. They called it "tyranny" and said that under this government, "you and your wives and your children are made slaves." They also said that the people's right to practice their religion was not safe. This was because it depended on a government where they had no say.

Congress clearly hoped to get French-speaking habitants (settlers) and English-speaking residents to join their cause. At the time, Congress knew that Governor Carleton had asked people to arm themselves to defend the King. The letter warned the people of Quebec about the danger of being sent to fight against France. This was a concern if France joined the war on the American side, which it eventually did in 1778.

Congress again said they wanted to treat Canadians as friends with shared interests. However, they also warned the people not to "reduce us the disagreeable necessity of treating you as enemies."

How the Second Letter Was Received

James Price, a merchant from Montreal, took the letter to Montreal. He also took a similar letter from the New York Provincial Congress. He shared them in the province. Many English-speaking merchants, who relied on the fur trade, were worried about the situation.

The French habitants were generally not convinced by appeals to English liberties. They did not know much about these ideas. However, they also did not strongly support the existing military government. Calls for them to join the army had little success. The habitants were more interested in supporting whoever was winning at the time, as long as they were paid for their supplies.

In the end, the Americans got limited support in Quebec. They managed to form two regiments that fought in the Continental Army. The 1st Canadian Regiment was formed in November 1775 during the early days of the invasion of Canada. The 2nd Canadian Regiment was formed in January 1776.

The Third Letter to Quebec

Writing the Third Letter

In September 1775, after the second letter failed to change public opinion, the American colonists launched an invasion of Quebec. This invasion started from Fort Ticonderoga and Cambridge, Massachusetts. It ended with the Battle of Quebec in late December 1775. The city was successfully defended by the British, and the American invaders settled in for the winter. After the battle, Moses Hazen and Edward Antill traveled from Quebec to Philadelphia to report the American defeat.

After hearing about the defeat, Congress decided on January 23, 1776, to write another letter to the Canadian people. The people on this committee were William Livingston, Thomas Lynch Jr., and James Wilson. The letter was approved the next day and signed by John Hancock.

What the Third Letter Said

Congress thanked the people of Quebec for the help they had given. They promised that more American troops were on their way to protect them. These troops would arrive before British reinforcements. Congress also told them that they had approved forming two battalions (groups of soldiers) in Canada to help the cause. The letter again invited the people to organize local and provincial meetings. These meetings could choose delegates to represent Quebec in the Continental Congress.

How the Third Letter Was Received

The French translation was again printed by Fleury Mesplet. However, it is not clear who wrote the letter or if du Simitière translated it this time. Hazen and Antill delivered copies of the letter to David Wooster, who was in charge of the American forces occupying Montreal. He made sure the letter was shared at the end of February.

The letter did not get much of a response. The people were unhappy about being paid for supplies with paper money. They also did not like the American occupation.

Conclusion: What Happened Next

The American invasion of 1775 was a huge failure. The Americans were forced to retreat back to Fort Ticonderoga. Quebec remained under British control, and its main cities were not threatened again during the war.

The main goal of these letters and other messages to the Canadian people was to get their political and military support for the American Revolution. This goal was generally not achieved. While Congress did manage to raise two regiments of Canadians (James Livingston's 1st Canadian Regiment and Hazen's 2nd Canadian Regiment), they did not have as many soldiers as hoped. The seigneurs (landlords) and the Catholic clergy mostly supported the British governor. Quebec remained a strong British colony largely because of the strong leadership of Guy Carleton. This happened despite attempts to bring the revolutionary spirit of the American colonies into Quebec.

Contents of the Letters

You can find the full text of these letters on Wikisource:

- Letter to the Inhabitants of the Province of Quebec, October 26, 1774 (English, French)

- Letter to the oppressed inhabitants of Canada, May 29, 1775 (English, French)

- Letter to the Inhabitants of the Province of Canada, January 24, 1776 (English, French)

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |