Levellers facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Levellers

|

|

|---|---|

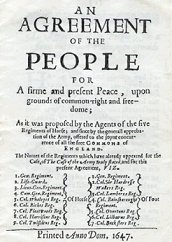

An Agreement of the People, a series of manifestos, published between 1647 and 1649, for constitutional changes to the English state often associated with the Levellers

|

|

| Leaders | John Lilburne Richard Overton William Walwyn Thomas Prince |

| Founded | July 1646 |

| Dissolved | September 1649 |

| Split from | Roundheads |

| Succeeded by | Radical Whigs |

| Ideology | Radicalism Republicanism Universal suffrage Populism |

| Political position | Left-wing |

| National affiliation | Roundheads |

| Military wing | Agitators |

The Levellers were a political movement active during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in England. They believed strongly in ideas like popular sovereignty (meaning the people should have the power), the right for more people to vote, fairness for everyone under the law, and religious tolerance (allowing people to practice any religion).

A key part of the Levellers' beliefs was their populism. This meant they focused on the idea that everyone has equal natural rights. They also reached out to ordinary people by writing pamphlets, sending petitions, and speaking to crowds.

The Levellers became well-known at the end of the First English Civil War (1642–1646). They were most important before the Second Civil War (1648–49) began. Many people in the City of London and some soldiers in the New Model Army supported their ideas.

They shared their beliefs in a document called "Agreement of the People". Unlike another group called the Diggers, the Levellers did not believe in common ownership of land. They thought people should own their own property, unless they agreed to share it.

The Levellers had offices in London inns and taverns. One famous place was The Rosemary Branch in Islington. They wore sprigs of rosemary in their hats to show they were Levellers. They also wore sea-green ribbons on their clothes.

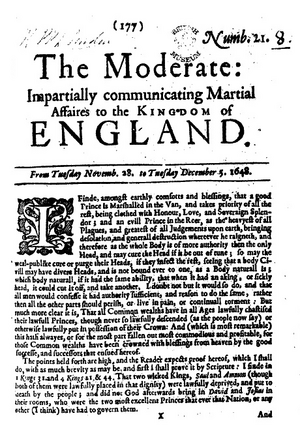

From July 1648 to September 1649, they published a newspaper called The Moderate. They were among the first to use petitions and pamphlets to share their political ideas. Printing and bookselling in London were very important to their movement.

After Pride's Purge (when some members of Parliament were removed) and the execution of Charles I, the powerful leaders of the Army, called "Grandees," took control. The Levellers and other groups who disagreed with them lost their power. By 1650, they were no longer a big threat to the government.

Contents

Where the Name "Levellers" Came From

The word "leveller" was used in the 1600s as an insult for poor people who rebelled in the countryside. For example, during the Midland Revolt of 1607, it described those who tore down hedges and walls during protests against land enclosures.

As a political group, the name first referred to some soldiers and their supporters in London. These people were thought to be planning to kill Charles I of England. But the name slowly became linked to John Lilburne, Richard Overton, and William Walwyn.

At first, Lilburne and his group thought the name was an insult. They preferred to be called "Agitators." The name "Levellers" suggested they wanted to bring everyone down to the same low level. This was not true.

However, the leaders eventually accepted the name because it was how most people knew them. After they were arrested in 1649, four leaders – Walwyn, Overton, Lilburne, and Thomas Prince – signed a paper where they called themselves Levellers.

A writer named Thomas Edwards first described the Levellers' ideas in his book Gangraena (1646). He attacked their radical ideas about everyone being equal, which he said did not respect the old laws.

What the Levellers Wanted

The Levellers' goals grew as soldiers in the New Model Army became unhappy after the First Civil War. Their main ideas were written in a document called the "Agreement of the People". This document was updated several times.

The final version, published in May 1649, called for many changes. They wanted almost all adult men to be able to vote. They also wanted fairer elections and elections every two years. They asked for religious freedom and an end to people being jailed for not paying debts.

The Levellers wanted to stop corruption in Parliament and the courts. They also wanted laws to be written in plain English, so everyone could understand them. Many historians believe they were the first political group to formally suggest modern democratic ideas.

Some people thought the Levellers were not fully democratic. This is because they did not want household servants or people who relied on charity to vote. They worried these people would just vote how their employers or helpers told them. Women were also excluded, as most married women depended on their husbands.

Some Levellers, like Lilburne, believed that English rights came from old laws like the Magna Carta. Others, like William Walwyn, did not think the Magna Carta was that important. Lilburne also wrote about the idea of a Norman yoke. This was the belief that the English people had lost their rights after the Norman Conquest and should get them back.

The Levellers believed in "natural rights". They felt the King had violated these rights during the Civil Wars. At the Putney Debates in 1647, Colonel Thomas Rainsborough said natural rights came from God's law in the Bible. Richard Overton thought liberty was something everyone was born with.

Key Moments in the Levellers' Story

In July 1645, John Lilburne was put in prison. He had criticized members of Parliament who lived comfortably while soldiers fought and died. He was freed in October 1645 after over 2,000 London citizens signed a petition asking for his release.

In July 1646, Lilburne was jailed again in the Tower of London. This time, he had accused his old army commander of being a Royalist supporter. The campaigns to free Lilburne from prison helped start the Leveller movement. Richard Overton was arrested in August 1646 for publishing a pamphlet against the House of Lords. While in prison, he wrote an important Leveller paper called "An Arrow Against All Tyrants and Tyranny."

Soldiers in the New Model Army chose "Agitators" to speak for them. These Agitators were part of the Army's General Council. By September 1647, some cavalry regiments chose new, unofficial agitators. They wrote a pamphlet called "The Case of the Army truly stated." This paper asked Parliament to dissolve itself within a year and make big changes to future Parliaments.

The senior army officers, called "Grandees," were angry about this. They ordered the unofficial Agitators to explain their ideas. These discussions, known as the Putney Debates, happened in St. Mary's Church, Putney, from October 28 to November 11, 1647. The Agitators were helped by civilians like John Wildman.

On October 28, an Agitator named Robert Everard presented a document called "An Agreement of the People". This document was very democratic and republican. It seemed to go against the "The Heads of the Proposals" that the Army Council had already agreed to. The "Heads of the Proposals" had many ideas for social fairness but needed the King to agree to them. The new Agitators did not trust the King. They wanted England to be set up "from the bottom up" by giving most adult men the right to vote.

The debates showed where the Parliament's supporters agreed and disagreed. For example, one officer asked if a foreigner who just arrived in England could vote under the "Agreement." He argued that a person needed a "permanent interest" (like owning property) to vote. This was where he and the Levellers disagreed. The debates often used the Bible to explain basic ideas. This was common because of the religious changes after the Reformation.

The Corkbush Field rendezvous on November 17, 1647, was the first of three meetings for the Army. Commanders Thomas Fairfax and Cromwell were worried about the Levellers' support. They decided to make "The Heads of the Proposals" the Army's official plan instead of the Levellers' "Agreement of the People." When some soldiers refused to accept this, they were arrested. One leader, Private Richard Arnold, was executed. At the other two meetings, the soldiers accepted the plan without protest.

The Levellers' biggest petition, called "To The Right Honourable The Commons Of England," was given to Parliament on September 11, 1648. About a third of all Londoners signed it.

On October 30, 1648, Thomas Rainsborough, a Member of Parliament and Leveller leader, was killed. His funeral was a huge Leveller protest in London. Thousands of mourners wore sea-green ribbons and rosemary in their hats.

On January 20, 1649, a new version of the "Agreement of the People" was given to the House of Commons.

At the end of January 1649, Charles I of England was tried and executed. In February, the Army leaders banned soldiers from sending petitions to Parliament. In March, eight Leveller soldiers went to the Army commander, Thomas Fairfax. They demanded their right to petition back. Five of them were kicked out of the army.

In April, 300 soldiers refused to serve in Ireland until the Levellers' plan was carried out. They were also kicked out of the army without pay. Later that month, in the Bishopsgate mutiny, soldiers made similar demands. Fifteen soldiers were arrested and tried by a military court. Six were sentenced to death. Five were pardoned, but Robert Lockyer, a former Leveller agitator, was hanged on April 27, 1649.

In 1649, John Lilburne, William Walwyn, Thomas Prince, and Richard Overton were put in the Tower of London. While they were there, they wrote a pamphlet called "An Agreement Of The Free People Of England" (May 1, 1649). It included ideas that are now laws in England, like the right to silence. It also had ideas that are not laws, like an elected judiciary.

Soon after, Cromwell attacked the "Banbury mutineers". These were 400 soldiers who supported the Levellers. Several mutineers were killed. Captain William Thompson, a leader, escaped but was killed a few days later. The other three leaders were shot on May 17, 1649. This ended the Levellers' support in the New Model Army, which was the most powerful group in the country. Even though Walwyn, Overton, and Lilburne were later freed, the Leveller movement was mostly crushed.

The Moderate Newspaper

The Moderate was a newspaper published by the Levellers. It was printed from July 1648 to September 1649.

Other Uses of the Name

The word "Levellers" was also used in other places. In 1724, during the Levellers Rising in Scotland, some men were called "Dykebreakers." They tore down stone walls. The most troublesome of these Levellers were sent to North America as punishment.

The word was also used in Ireland during the 1700s. It described a secret group that was similar to the Whiteboys.

See Also

- List of liberal theorists

- English Dissenters

- Good Old Cause

- Green Ribbon Club

- Hugo Black

- Kett's Rebellion (1549)

- Chartism

- Republicanism in the United Kingdom

- Edward Sexby (1616–1658)

- Peasants' Revolt

- Libertarianism

- United States Bill of Rights

- Gerrard Winstanley

- Norman yoke

- Pre-Marxist communism