Louis Slotin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louis Slotin

|

|

|---|---|

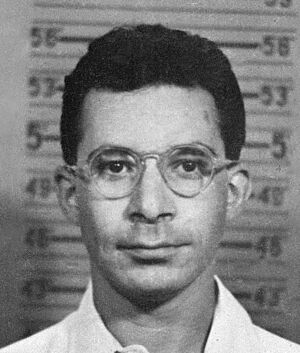

Slotin's Los Alamos badge photo

|

|

| Born |

Louis Alexander Slotin

1 December 1910 Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

|

| Died | 30 May 1946 (aged 35) |

| Cause of death | Acute radiation syndrome |

| Education | |

| Occupation | Physicist and chemist |

| Known for | Criticality tests on Plutonium & nuclear weapons assembling, the Dollar unit of reactivity |

Louis Alexander Slotin (/ˈsloʊtɪn/ sloht-in; 1 December 1910 – 30 May 1946) was a Canadian physicist and chemist. He was an important part of the Manhattan Project, which was a secret effort during World War II to build the first atomic bomb.

Born in Winnipeg, Canada, Slotin was a very smart student. He earned his science degrees from the University of Manitoba. Later, he got his PhD in chemistry from King's College London in 1936. After that, he worked at the University of Chicago, helping to build a machine called a cyclotron.

In 1942, Slotin joined the Manhattan Project. His job was to do dangerous experiments with uranium and plutonium. These tests helped figure out the exact amount of material needed to start a nuclear chain reaction. This amount is called the critical mass. After the war, he kept working at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

On May 21, 1946, Louis Slotin accidentally caused a nuclear reaction during an experiment. This released a burst of strong radiation. He was rushed to the hospital but died nine days later on May 30. Slotin was the second person to die from a criticality accident. The first was his colleague, Harry Daghlian, who was also exposed to radiation from the same plutonium core.

Some people called Slotin a hero because he quickly stopped the reaction. This action may have saved the lives of his co-workers. However, other scientists believed his actions before the accident were risky and could have been avoided. His story has been told in many books and movies.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Louis Slotin was the oldest of three children. His parents were Jewish refugees from Russia who settled in Winnipeg, Canada. He grew up in the North End of Winnipeg, an area with many immigrants. From a young age, Slotin was an excellent student. His younger brother, Sam, said Louis was very focused and could study for many hours.

At 16, Slotin started studying science at the University of Manitoba. He was so good that he won gold medals in both physics and chemistry. He earned his first science degree in geology in 1932 and a master's degree in 1933. With help from a teacher, he got a scholarship to study at King's College London. There, he studied electrochemistry and photochemistry.

Time at King's College London

While at King's College London, Slotin was also a good amateur boxer. He even won the college's boxing championship. He earned his PhD in physical chemistry in 1936. His research was about how unstable molecules form during chemical reactions.

Career in Science

University of Chicago Work

In 1937, Slotin joined the University of Chicago as a research assistant. This was his first experience with nuclear chemistry. He helped build the first cyclotron in the Midwest United States. A cyclotron is a machine that speeds up tiny particles.

From 1939 to 1940, Slotin worked with Earl Evans, a biochemistry expert. They used the cyclotron to make radiocarbon (like carbon-14). They also showed that plant cells could use carbon dioxide to make sugars.

Slotin might have been there when the first nuclear reactor, called "Chicago Pile-1," started on December 2, 1942. His knowledge of radiobiology (the study of radiation's effects on living things) caught the attention of the U.S. government. This led to his invitation to join the Manhattan Project. He worked on making plutonium and later moved to the Los Alamos National Laboratory in December 1944.

Work at Los Alamos

At Los Alamos, Slotin's job was to perform dangerous criticality tests. These tests involved bringing nuclear materials very close to the point where they would start a nuclear chain reaction. Scientists called this "tickling the dragon's tail." This name came from physicist Richard Feynman, who said it was like "tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon."

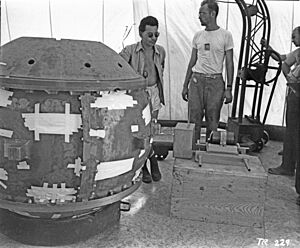

On July 16, 1945, Slotin put together the core for the "Trinity" test. This was the first time an atomic device was exploded. Because of his skill in assembling nuclear weapons, he became known as the "chief armorer of the United States."

Harry Daghlian's Accident

On August 21, 1945, Slotin's colleague, Harry Daghlian, was doing a similar criticality experiment. He accidentally dropped a heavy brick onto a plutonium core. This core was later called the "demon core." Daghlian was exposed to a large amount of neutron radiation. He became very sick with acute radiation poisoning and died 25 days later.

Planning to Teach Again

After World War II, Slotin didn't want to be involved in the nuclear weapons project anymore. He said he was "disgusted" with his part in it. However, his skills were still needed at Los Alamos. He was one of the few people left who knew how to assemble the bombs. He hoped to go back to teaching and research at the University of Chicago. He started training Alvin C. Graves to take over his job at Los Alamos.

The Criticality Accident

On May 21, 1946, Louis Slotin was performing an experiment with seven colleagues watching. He was putting two halves of a beryllium sphere around a plutonium core. Beryllium helps reflect neutrons, making the reaction more likely. He was holding the top half with his left hand and keeping the halves separate with a screwdriver in his right hand. This was not the usual safe way to do the experiment.

At 3:20 p.m., the screwdriver slipped. The top beryllium half fell, causing a sudden nuclear reaction and a burst of strong radiation. The scientists in the room saw a blue flash of light and felt a wave of heat. Slotin felt a sour taste in his mouth and a burning feeling in his left hand. He quickly pulled his hand up, lifting the beryllium half and stopping the reaction. But he had already received a deadly dose of radiation.

Right after the accident, Slotin asked a colleague to get the radiation badges from a locked box. This was to try and measure how much radiation everyone received. However, a later report suggested that a heavy dose of radiation can make a person unable to think clearly. As soon as Slotin left the building, he vomited, which is a common sign of intense radiation exposure. His colleagues rushed him to the hospital, but the damage was too severe.

Slotin's Final Days

Despite getting a lot of medical care, Slotin's condition could not be cured. His parents were flown from Winnipeg to be with him. They arrived four days after the accident. By the fifth day, his health got much worse.

Over the next four days, Slotin suffered greatly. He had severe diarrhea, swollen hands, and large blisters. He also had internal radiation burns throughout his body. One doctor described it as a "three-dimensional sunburn." By the seventh day, he was sometimes confused. His lips turned blue, and he was put in an oxygen tent. His body functions completely failed, and he went into a coma. Slotin died at 11 a.m. on May 30, with his parents by his side. He was buried in Winnipeg.

Other Injuries

Alvin C. Graves, who was standing closest to Slotin, also got very sick from radiation. He was in the hospital for several weeks but survived. He lived with long-term problems with his nerves and vision. Other people in the room also suffered from radiation exposure.

Radiation Measurement

The exact amount of radiation received in these accidents is hard to know. Much of the radiation was from neutrons, which were difficult to measure back then. The scientists were not wearing their personal radiation badges during the accident.

Later, scientists tried to estimate the doses. They looked at the amount of sodium that became radioactive in the victims' blood and urine. This was caused by neutron radiation. They estimated that Slotin received a very high dose, much higher than what a human can survive.

Legacy

After Slotin's accident, Los Alamos stopped all hands-on criticality work. From then on, testing of nuclear cores was done using machines controlled from a safe distance. This was to prevent similar accidents.

On June 14, 1946, a poem called "Slotin – A Tribute" was written in the local newspaper. It praised Slotin for his quick actions. The official story was that Slotin was a hero for stopping the reaction and saving his colleagues. Alvin C. Graves, who was there, supported this view. However, another witness, Raemer E. Schreiber, later said that Slotin was using unsafe methods.

Slotin's accident has been shown in movies and books. The 1947 film The Beginning or the End shows a scientist dying after touching radioactive material. The 1955 novel The Accident tells the story of a scientist suffering from radiation poisoning. The 1989 film Fat Man and Little Boy has a character based on Slotin.

In 1948, Slotin's colleagues created the Louis A. Slotin Memorial Fund. This fund brought famous scientists like Robert Oppenheimer to give lectures on physics. An asteroid discovered in 1995 was named 12423 Slotin in his honor.

The Dollar Unit of Reactivity

Louis Slotin was the first to suggest the name "dollar" for a special unit in nuclear physics. It describes the range of reactivity between a self-sustaining chain reaction and a "prompt critical" reaction. A nuclear reactor usually works between 0 and a dollar. Explosions happen above a dollar. One hundredth of a dollar is called a cent.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Louis Slotin para niños

In Spanish: Louis Slotin para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |