Lovett Fort-Whiteman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lovett Fort-Whiteman

|

|

|---|---|

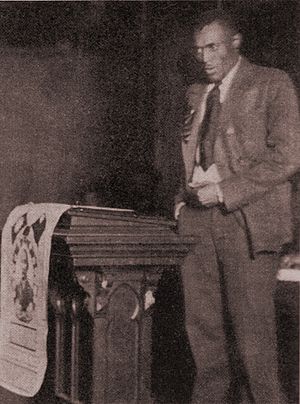

Fort-Whiteman at the founding of the ANLC, 1925.

|

|

| Born | December 3, 1889 Dallas, Texas, USA

|

| Died | January 13, 1939 (aged 49) Kolyma, Siberia, USSR

|

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Political activist, Comintern functionary |

Lovett Huey Fort-Whiteman (born December 3, 1889 – died January 13, 1939) was an American political activist. He worked with the Communist International, a group that promoted communism around the world. Fort-Whiteman died in the Soviet Union while he was imprisoned.

In 1924, he became the first black American to attend a special training school in the Soviet Union. Later, he helped start the American Negro Labor Congress. This group was connected to the Communist Party, USA. Time magazine once called him "the reddest of the blacks."

Contents

Lovett Fort-Whiteman's Early Life

Lovett Huey Fort-Whiteman was born in Dallas, Texas, on December 3, 1889. His father, Moses Whiteman, was born into slavery. He moved to Texas and worked as a janitor and a small cattle rancher. Lovett's mother, Elizabeth Fort, was 15 when she married Moses. Lovett was their first child.

Lovett received a good education for an African-American child at that time. He went to one of the few high schools in the American South open to black students. After high school, he attended the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, around 1906. He graduated as a machinist.

After Tuskegee, Fort-Whiteman started studying at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee. He wanted to become a medical doctor, but he did not finish his studies there.

By 1910, his father had passed away. Fort-Whiteman moved with his mother and younger sister to Harlem in New York City. He worked as a hotel bellman to support his family. At this time, he dreamed of becoming a professional actor.

Time in Mexico and Return to the U.S.

Fort-Whiteman soon gave up his acting dreams. He spent two or three years in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. There, he worked as an accounting clerk for a company that made rope. He learned to speak Spanish very well and also studied some French.

He was greatly inspired by the Mexican Revolution in 1915. This revolution aimed to bring reforms against wealthy landowners and the Roman Catholic church. Fort-Whiteman became a strong believer in changing society through trade unions. He joined a group called Casa del Obrero Mundial (House of the World Worker). This group tried to push the revolution further by starting a strike, but it was stopped.

In 1917, Fort-Whiteman left Yucatán. He traveled as a sailor to Havana, Cuba, and then to Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. He got off the ship there and went to Montreal. He used the pseudonym "Harry W. Fort" and secretly returned to the United States. He pretended to be a railroad dining car waiter.

Activism in New York City

Back in New York City, Fort-Whiteman met important black socialists like A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen. They published a magazine called The Messenger. Fort-Whiteman took courses at the Rand School of Social Science. This was a socialist school run by the Socialist Party of America, which he also joined. At the Rand School, he met other people who would become important in global political movements. These included Sen Katayama from Japan and Otto Huiswoud from British Guiana.

In 1918, Fort-Whiteman became the "Dramatic Editor" for The Messenger. He was part of the Harlem Renaissance, a lively black cultural movement. This movement focused on artistic and political growth for the "New Negro." Fort-Whiteman even wrote two short stories for The Messenger. These stories explored relationships between different races.

He also met anarchist cartoonist Robert Minor, who was also from Texas. Minor had visited Soviet Russia in 1918 and saw the Bolshevik Revolution firsthand. Fort-Whiteman followed his friend and joined the Communist Labor Party of America in September 1919.

In October 1919, Fort-Whiteman was arrested in St. Louis. He was speaking to a small group that included a military informer. As a known black Communist, he was closely watched by the Bureau of Investigation. They called him a "dangerous agitator." Fort-Whiteman was accused of breaking the Espionage Act. This law made it illegal to speak against the United States. He denied saying anything like that. He stayed in jail for months but avoided a long prison sentence.

Becoming a Black Communist Leader

From 1920 to 1922, the American Communist movement operated secretly. Fort-Whiteman likely remained a member through various changes and mergers. He reappeared publicly in February 1923 as an editor for The Messenger. However, his connection to the Workers Party of America (WPA), a legal Communist group, was not public yet. He only publicly announced his Communist ties in January 1924. This was in an article for The Daily Worker, the WPA's official newspaper.

In February 1924, Fort-Whiteman was one of 250 delegates at the "Negro Sanhedrin." This was a meeting in Chicago about issues affecting black workers. The WPA helped organize it through its New York group, the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), led by Cyril Briggs. Fort-Whiteman spoke for the WPA/ABB. He pushed for their goals, which included ending racial segregation in housing. They also wanted fair contracts for tenant farmers, an end to colonialism in Africa, and U.S. recognition of the Soviet Union.

During the 1920s, many African-Americans moved from the South to Northern cities. This was called the "Great Migration". The American Communist movement tried to help with the problems that came with this move. They started a short-lived group called the Negro Tenants Protective League. This group encouraged rent strikes and other actions to bring about change. Fort-Whiteman was a top leader in the Communist Party's "Negro work." He spoke at the group's first meeting in Chicago on March 31, 1924. Other Workers Party leaders like Robert Minor and Otto Huiswoud were also there.

Leading the American Negro Labor Congress

In the spring of 1925, Fort-Whiteman joined his Workers (Communist) Party friends Otto Hall and Otto Huiswoud. They were among 17 black leaders who officially called for the American Negro Labor Congress (ANLC). The Communist Party created the ANLC to replace the African Blood Brotherhood. The ANLC was founded at a meeting of 500 people in Chicago in late October of that year.

Many delegates at this meeting were from trade unions and community groups. They were working-class people, not just intellectuals. One historian said these delegates were "the sorts of blacks the Communists felt the NAACP and Urban League forgot."

The ANLC's early success was largely due to Fort-Whiteman's efforts. He was chosen to lead the ANLC's Provisional Organizing Committee. He traveled across the South and Northeast. He spoke to many black community groups, asking them to support the new organization. He argued that a new group was needed to "present the cause of the Negro worker." His successful organizing made him well-known. The magazine Time called him "the reddest of the blacks."

Arrest and Death

In early 1937, the Soviet secret police began a huge campaign of arrests. This was part of the Great Purge. They targeted people they thought were spies, saboteurs, or disloyal. Lovett Fort-Whiteman asked for permission to return home to the United States, but his request was denied. Three weeks later, he was accused of having "counterrevolutionary" ideas. On July 1, 1937, he was sentenced to five years of internal exile. He was first sent to Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan, where he worked as a teacher.

Internal Communist Party documents identified Lovett Fort-Whiteman as a Trotskyist. This was a political idea that differed from the main Soviet leadership. A report from the mid-1930s said, "Lovett Fort-Whiteman, a Negro Comrade, showed himself for Trotsky." In 1938, a Communist Party representative wrote, "Whiteman is a Trotskyist."

The arrests and punishments continued to increase in 1938. On May 8, 1938, Fort-Whiteman's sentence was reviewed. He was given a stricter sentence of five years of hard labor in the Gulag. The Gulag was a system of harsh work camps. Fort-Whiteman was sent to Kolyma in Siberia. This was a very cold and difficult part of the Soviet Far East.

In Kolyma, Fort-Whiteman was held in a camp that was part of the Sevvostlag system. These camps were run by the Dalstroy State Trust. They focused on mining gold and tin in freezing conditions. The food given to prisoners was very little and poor. The hard work and severe winter weather weakened Fort-Whiteman. His health quickly failed. An acquaintance of Robert Robinson, who saw Fort-Whiteman, said he was treated very harshly for not meeting work goals. He was described as "a broken man."

On January 13, 1939, Lovett Fort-Whiteman died from an illness related to malnutrition. He was 49 years old. His death certificate stated he was likely working at the Taezhnik mine. The hospital where he died was also known as the Orotukan hospital.

See also

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |