Manuscript culture facts for kids

A manuscript culture is a time when people mostly used hand-written books to share and keep information. It was a step in history between oral culture (where stories were only spoken) and print culture (where books were printed). Europe started this stage in ancient times.

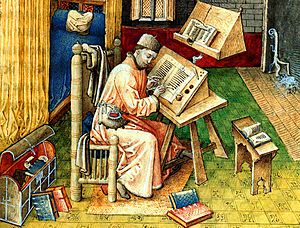

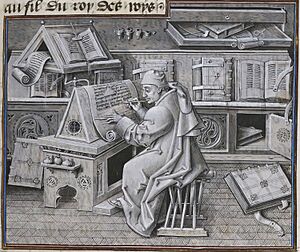

In the early Middle Ages, monks often copied manuscripts by hand. They copied not just religious books, but also texts about astronomy, herbals (books about plants and medicine), and bestiaries (books about animals). Later, manuscript culture moved from monasteries to cities. Universities also became important in making and trading these books. This period was known for wanting books to be clear, easy to find information in, and simple to read aloud. This desire for order grew after a big church meeting in 1215 and a religious movement called the Devotio Moderna. Books also started being made on paper instead of vellum (animal skin).

Contents

- Medieval Books and Learning

- Later Manuscript Culture

- Images for kids

- See also

Medieval Books and Learning

How Manuscript Culture Began

In England, the use of manuscripts became very important around the 10th century. This doesn't mean books weren't important before, but that people started relying on them much more. At this time, doctors were learning new things about the human body and how plants affected it. They wrote down this information and shared it through people who could read and write.

During the Middle Ages, Catholic monasteries and cathedrals were big centers of learning. So, it made sense that these important texts ended up with the monks.

These monks carefully copied the information. They didn't just copy blindly, though. For example, with herbals, monks sometimes improved the texts. They fixed mistakes and made the information useful for their local area. Some monasteries even grew the plants mentioned in the books! This shows how practical these texts were for the monks. They focused on real, useful information, especially since plants and medicine were closely linked then.

For bestiaries, monks also copied older texts. But unlike plants, they couldn't grow animals in their gardens. So, they often took the information as it was. This allowed writers to add more details and stories. They often gave animals special moral meanings, making these texts similar to traditional myths.

The Business of Books

By the 13th century, Paris became the first city with a big business for manuscripts. People would pay bookmakers to create specific books for them. Paris had enough rich people who could read to support those who made manuscripts for a living. This was a big change! Book production moved from monks in monasteries to booksellers and scribes in cities.

Many people worked as scribes, but they also worked together. Commercial workshops in Paris often shared jobs. For example, two or more artists might work on decorating the same manuscript.

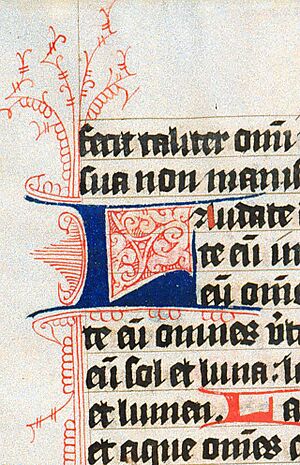

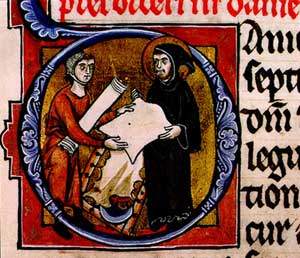

In monasteries, scribes and illuminators (artists who decorated books) often split the work. The scribe would leave space for a fancy letter at the start of a new paragraph. Later, an illuminator would paint it in.

The Pecia System

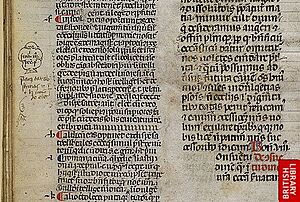

The pecia system started in Italy in the early 1200s. It became a common way to make books at the University of Paris later that century. This system broke books into sections called peciae. Students or others could rent these sections one by one to copy them.

Each pecia was usually about four pages long. This allowed for quick turn-over, so many students could copy different parts of a book at the same time. This system meant a book could be copied much faster than if one person did it all.

The original set of peciae for a book, from which all copies were made, was called the exemplar. Making an exemplar was supposed to be a careful process. University teachers would edit a new work and give it to a stationer (a kind of bookseller). The stationer would copy it into peciae, check them carefully, and then university officials would approve them and set a rental price. Only then could students rent the peciae.

In reality, stationers often just found books they thought would be popular. They focused on getting books quickly, not always on perfect quality. If a book seemed like it would be a "best seller," the stationer would copy the best available text fast. They would correct their exemplar-peciae as much as time allowed.

Booksellers in Paris

King Philip the Fair of France (1285–1314) put a small tax on all goods. But in 1307, he made an exception for university booksellers, called librarii universitatis. This meant they didn't have to pay the tax if they promised to follow university rules.

The word librarius was a general term for anyone involved with books, from a scribe to a bookseller or librarian. A stationarius (stationer) was a specific type of librarius who rented out peciae. Both types bought and sold used books, made new ones, and were regulated by the university. The main difference was that stationers also rented out peciae.

Rules for Booksellers

The promises that librarii had to make to the universities for their tax break were very strict, especially about selling used books. They were supposed to act more like helpers between the seller and buyer. Their profit was very limited. They also had to display used books clearly, give a fair price estimate, and connect buyers directly with sellers.

Booksellers had to promise not to pay too little when buying or charge too much when selling. Stationers rented out copies of useful texts, one section at a time, so students and teachers could make their own copies. Both fees were set by the university. Booksellers had to pay a bond (a sum of money) to guarantee they would follow the rules.

It wasn't just booksellers that universities regulated. They also made rules for parchment makers. They didn't want parchment makers to hide good parchment from university members who wanted to buy it. There was a lot of demand for parchment from other places, like the government, businesses, and religious groups. These groups often paid more than the university's set price. So, universities often regulated parchment prices too.

Benefits for Booksellers

Even with many rules, being a bookseller had benefits. They could make and sell books, decorate them, or write for anyone they wanted, like the King's Court or wealthy people. They just had to meet their promises to the university. In fact, most of their business was outside university rules. They could charge whatever the market would allow to non-students or teachers.

From 1300 to 1500, the job of libraire (bookseller) was a closed position. You could only become one if someone else quit or died. Besides cheap books, only libraires were allowed to sell books in Paris. The university basically gave booksellers a special right to sell books.

Later Manuscript Culture

What Changed in Later Manuscripts

The period of later manuscript culture was roughly from the mid-1300s to the 1400s. It happened before and at the same time as the printing press. In this time, people paid close attention to how texts were punctuated and laid out. Reading aloud was very important. The meaning of every sentence had to be super clear, with little room for different interpretations. This was because preaching became very popular after the Fourth Lateran Council.

People also tried to make spellings correct, especially for Bibles. This made many texts more uniform. In this period, special manuscripts called emendatiora were made. These combined old, surviving texts with the most current and accepted versions.

Later manuscripts also had many helpful features to find your way around the text. These included:

- Tables of contents

- Lists of chapters (at the beginning of each book or the whole work)

- Running headlines (titles at the top of each page)

- Detailed colophons (notes at the end of a book with info about its making)

- Page numbers using Arabic numerals (like 1, 2, 3)

- Subject indexes (like the index at the back of a book)

Other changes included making the rubric (a special heading or note, often in red ink) much longer. It also included more information, like the translator or original writer. These changes show a desire for books to be uniform, easy to use, and accurate. These were many of the same goals that the printing press later achieved.

Making Manuscripts in the 1400s

New ways of making manuscripts appeared in the Low Countries (like modern-day Belgium and Netherlands) in the late 1300s. This marked a new era. People wanted books to be uniform and clear, both in how they were described and how the text itself was copied and corrected. This meant better organization, especially in monastery writing rooms called scriptoria.

Historians used to think this period was messy, with poor quality paper books. But the quality of the paper didn't affect the text. People switched from parchment to rag paper. A new style of writing called hybrida even combined old handwriting with the style used in printed books. It was still easy to read. Also, in the early 1400s, people started using different writing styles for different parts of a text. Rubrics and colophons had their own unique script. All these changes aimed for better accuracy and led to clear rules for making books.

Uniformity in Different Books

Many manuscripts were made with different sizes, layouts, writing styles, and decorations. But they all used the same text, even if many different scribes copied them. They were corrected so carefully that there were very few differences in the text itself. This suggests that someone was guiding the scribes. It also shows a new focus on scholarly accuracy that wasn't as strong with university booksellers. New religious groups in the 1300s emphasized this. Correcting and improving texts became as important as copying them.

Rules for Correction: The Opus Pacis

In 1428, a German monk named Oswald de Corda wrote a book called the Opus Pacis (Work of Peace). It had two parts, mainly about spelling and accents. Oswald wrote it to calm his fellow monks, who were worried about missing even single letters in copies of texts. This shows how extreme the new concern for uniformity was. His audience was scribes who were almost "neurotic" about being exact. He wanted to strengthen older rules about making manuscripts, but also to correct them.

The Old Rules of 1368

Oswald especially wanted to change the Statuta Nova (New Statutes) of 1368. These rules said no one could correct copies of the Old and New Testament unless they used specific approved exemplars. Anyone who corrected texts differently was publicly shamed and punished. Oswald's Work of Peace said that correctors shouldn't do pointless work by over-correcting. He saw correction as a helpful act, not a strict command. It was for improving a text, and while it followed rules, they weren't so strict that they stopped people from making improvements. This was a change from older rules that had many lists and strict commands for scribes, which were often ignored. Oswald disagreed with simply picking one exemplar and copying it, even if the scribe knew it had errors.

New Correction Rules

Oswald carefully explained how to correct different versions of the same text. He said scribes shouldn't just correct based on one version, but should think and use good judgment. He also said that for Bibles, scribes shouldn't immediately update old spellings, because this had caused more differences in texts. Oswald also created a standard set of abbreviations. However, he said scribes should respect national differences, especially after the Western Schism (a split in the church). But scribes were right to correct texts with different Latin dialects, especially if they used old Latin verb forms.

The Valde Bonum

In his introduction to the Opus Pacis, Oswald compared his work to the Valde Bonum, an earlier guide written during the Great Schism. The Valde Bonum tried to set universal spellings for the Bible. It said that correctors didn't need to change a text to match an exemplar from a certain region. Instead, they could use local spelling practices as a standard. It recognized that centuries of use and copying across different countries had affected spellings. Oswald included many of these ideas in his Opus Pacis. It was copied and used widely, spreading from Germany to Ireland. By the 1480s, it became a standard, especially for the Devotio Moderna and reformed Benedictines. Opus Pacis even became a general term for any book of its kind. The last known copy was made in 1514, showing that correcting manuscripts was still important 60 years after printing began.

Manuscripts and Preaching

In later manuscript culture, written pages became very important to religious groups again. Monastery writing rooms, which had been less important, started to thrive. They believed that writing sacred books was the most fitting and holy work. Copying these books was like "preaching with one's hands."

Sermons were not super important in the 1200s. But by the 1400s, after the Fourth Lateran Council emphasized preaching, they became extremely important. New groups focused on preaching, leading to more teaching about pastoral theology in schools. Preaching became a key part of religious services. This made uniform manuscripts with many tools for easy reference, reading, and clear speaking very necessary.

The Devotio Moderna and reformed Benedictines relied on reading religious texts for guidance. The written word was given a high level of importance. In fact, monasteries bought many printed books, becoming the main customers for early printing presses. This was because of their strong focus on preaching. Without these groups, there might not have been such a need for texts and printers. Printing grew quickly in Germany and the Low Countries, where the Devotio Moderna was strong. This was also where later manuscript culture began, because of the shared desire for uniformity.

Manuscripts and the Printing Press

Around 1470, the shift from handwritten books to printed ones began. The book business changed a lot. By this time, German printing presses had reached northern Europe, including Paris. By 1500, printed books stopped trying to look like manuscripts, and manuscripts started imitating printed books. For example, during the reign of King Francis I (1515–1547), the king's handwritten manuscripts looked like printed Roman type.

Good quality rag paper appeared before the printing press. But once printing arrived, parchment makers lost most of their business. Paper was not just okay, it was preferred. Printers and scribes stopped using parchment almost entirely. Many libraries didn't like these changes because they felt books lost their unique character. Many printed books and manuscripts were even made with the same paper, often showing the same watermarks (designs in the paper) from the paper dealer.

Manuscripts were still written and decorated well into the 1500s, some even close to 1600. Many illuminators continued to work on manuscripts, especially the Book of Hours. This was the most common manuscript produced from the 1450s onwards and was among the last types of manuscripts created. By the 1500s, however, artists hired by nobles or royals mostly decorated manuscripts. These books were made only for special events, like royal births, weddings, or other big occasions. The number of copyists dropped a lot, as these manuscripts were not for everyone to buy.

The old way of making books, where libraries gave sections to scribes and illuminators, fell apart. The new system, based on rich patrons, didn't support them. Libraries, not scribes, became printers. They had many manuscripts and slowly added printed books until printed books filled their collections. However, the cost and risks of making books increased with printing. Still, Paris and northern Europe (especially France) had been major centers for manuscript production and remained important in the printed book market, second only to Venice.

How Books Were Copied and Printed

Scribes sometimes worked in ways similar to printers, though there were subtle differences. Before printing or paper, pages on vellum (animal skin) were folded to form a quire (a section of a book). Printed books also bound multiple quires to form a codex (a book). They were just made of paper.

Manuscripts were also used as exemplars (originals) for printed books. Lines were counted and marked in advance, and the printed layout copied the manuscript's text. But within a few generations, printed books became the new exemplars. This created "family trees" of books. Many printed sources were checked against earlier manuscripts if their quality seemed low. This led to the creation of stemma, or lines of descent among books. Manuscripts gained new importance as sources to find older or better versions of a text. For example, Erasmus found old, reliable manuscripts from the medieval period because he wasn't happy with printed Bibles.

Christine de Pizan and New Art Styles

The Epistre Othea (Letter of Othea to Hector), written in 1400, shows the interesting shift from manuscript culture to the Renaissance and humanistic print culture. It was a retelling of the classical story of Othea in a decorated manuscript. But it also shared many new ideas from the Renaissance. Christine de Pizan created it for Louis of Orleans, who was next in line for the French throne.

The book had over 100 images. Each chapter started with an image of a mythological figure or event. It also had short story verses and text for Hector. Each prose passage had a labeled explanation, trying to find a humanistic lesson from the myth. Every explanation ended with a quote from an ancient philosopher. Other short prose passages, called allegories, ended a section. They gave lessons for the soul and a Latin Bible quote.

Christine de Pizan combined old images with new humanistic values, which are usually linked with printing. Her work was based on Ovid's stories, and many Ovidian myths were traditionally decorated in the Middle Ages. She also included astrology, Latin texts, and many classical myths to expand Ovid's story, keeping her humanist goals. This mix also led to the use of illuminatio, or using light as color. Her Othea was like a bricolage, mixing old traditions without trying to create a completely new masterpiece. It was done in a style called ordinatio, a layout that showed the meaning of the images' organization.

The Othea showed a later manuscript culture that included violence, action, and gender challenges in literature. Anger was shown in relation to gender, moving away from older ideas. Women were no longer just driven by wild emotions, but had anger that came from well-thought-out character interactions. The Epistre Othea was Christine's most popular work, even though many different versions existed. Because manuscripts were copied by hand, especially the decorations, the visual experience was not always the same. Each copy had different cultural elements, and many had completely different philosophical and religious meanings. Only later copies that used woodcuts to reproduce the images created a truly "authorial" (official) version of the manuscript. It also existed partly because of the printing press. Since Bibles were now printed, non-religious texts were available for detailed decoration.

Creating a Famous Author with Chaucer

William Caxton's Role

While using medieval manuscripts as originals, many printers tried to put humanist values into the text. They wanted to create a uniform work, similar to what the Devotio Moderna wanted. Early editors and publishers needed clear, official works to define a culture. William Caxton (born around 1415–1424, died 1492), an editor, was very important in shaping English culture and language. He did this through his official versions of Geoffrey Chaucer's works. Caxton was a bridge figure, trying to connect manuscript culture with a more humanist print culture through Chaucer's writing. He specifically tried to make Chaucer seem like classical writers and European poets.

Chaucer as a Humanist

Caxton tried to make Chaucer into an English Petrarch or Virgil (famous classical writers). He realized that new 16th-century versions of Chaucer's work needed to respect 14th-century versions. His Chaucer went beyond medieval ideas and became timeless, fitting humanist ideals. This meant creating a literary family tree that referred to older medieval originals. Through Caxton's editing, Chaucer was presented as an early supporter of the Renaissance. He was shown as someone who disliked older Gothic and medieval culture and who saved the English language.

he by hys labour enbelysshyd/ornated and made faire our englisshe/in thys Royame was had rude speche & Incongrue/as yet it appiereth by olde bookes/whych at thys day ought not to haue place ne be compared emong ne to hys beauteuous volumes/and aournate writynges

Caxton and "Olde Bookes"

Caxton wanted to get rid of "old bookes" that were typical of medieval culture. To do this, he updated old words and added Latin spellings. He removed the influence of manuscript culture, which allowed readers to have some say in the text. Caxton believed that printed books could set a clear authorship. This meant readers wouldn't feel it was okay to change the text or add notes. He thought that cheap versions of this official Chaucer would help different readers develop shared economic and political ideas, uniting England's culture. His version of Chaucer was well-liked by Henry VII of England, who decided to spread it to help give England a common cultural background.

How Books Were Seen

For most people in the late age of manuscript culture, books were first and foremost codices (bound books), ways to carry text, whether they were printed or handwritten. The cost of getting them set the standard, and printed books slowly became more common. William Caxton said his readers could get them "good cheap" (cheaply), and that the quality of the text was improved or at least equal in print. Many lists of books from that time didn't separate handwritten and printed books. However, in auctions, a clear difference was made, as anything handwritten sold for a higher price.

Common Ideas and New History

Many scholars of print culture and classicists (people who study ancient Greece and Rome) have argued that manuscripts had mistakes because of blind copying and a fixed manuscript culture. They said that once a mistake was made, it would be repeated forever and made worse by not changing from the previous copy. This showed a clear advantage of printing. The famous classicist E.J. Kenney said that "medieval authors, scribes, and readers had no notion of emending a text, when they were confronted with an obvious error in their exemplars, other than by slavishly copying the readings of another text."

However, there was a lot of variety in manuscripts, with changes in style and a willingness to change from earlier copies. This can be seen in a copy of Jerome's Epistolae Morale compared to a copy of Cicero's Letters, both from the 16th century. Many historians, especially medievalists, argue that the late 14th and 15th centuries saw reforms that included many features later linked with printing. Many classicists also naturally looked at copies of classical texts from that time, which weren't always typical of other, more important works. Medievalists believe that universality and uniformity were seen in some late manuscripts, along with other changes usually linked with printed books.

Much of the recent study on later manuscript culture came from Elizabeth Eisenstein, a key scholar of print culture. Eisenstein argued that the invention of the printing press led to the Renaissance and the social conditions needed for it. She said the printing press freed readers from many limits of manuscripts. However, she didn't go into detail about the state of manuscript and scribal culture in the late 14th and 15th centuries. She described the conditions in Germany when the printing press was invented in Mainz, and the scribal culture in England and France, to compare print culture and manuscript culture. She didn't describe Italian humanists in Florence or new religious groups like the Modern Devotion in the Low Countries and Germany. These included the Windesheim Congregation, which Oswald de Corda was part of. Many medievalists, like Mary A. Rouse and Richard H. Rouse, responded by trying to give a more detailed account of later manuscript culture and its unique features. This is part of the belief that changes happened during this period that print culture scholars, like Eisenstein, didn't notice.

Images for kids

See also

- Book

- Codex

- Historical document

- Illuminated manuscripts

- List of Hiberno-Saxon illustrated manuscripts

- List of manuscripts

- List of New Testament papyri

- List of New Testament uncials

- Manuscript

- Manuscript format

- Manuscript processing

- Scriptorium