Mario Molina facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mario Molina

|

|

|---|---|

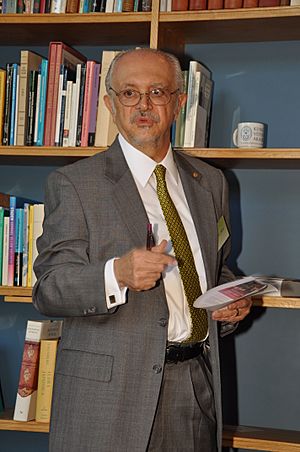

Molina in 2011

|

|

| Born |

Mario José Molina Henríquez

March 19, 1943 Mexico City, Mexico

|

| Died | October 7, 2020 (aged 77) Mexico City, Mexico

|

| Education |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Vibrational Populations Through Chemical Laser Studies: Theoretical and Experimental Extensions of the Equal-gain Technique (1972) |

| Doctoral advisor | George C. Pimentel |

| Doctoral students | Renyi Zhang |

Mario José Molina Henríquez (March 19, 1943 – October 7, 2020) was a Mexican chemist. He helped discover the Antarctic ozone hole. He also won the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. This was for his work on how chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) gases could harm Earth's ozone layer. He was the first scientist born in Mexico to win a Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He was also the third Mexican-born person to receive any Nobel Prize.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Mario Molina was born in Mexico City. His parents were Roberto Molina Pasquel and Leonor Henríquez. His father was a lawyer and a diplomat. This means he worked for his country in other nations. His mother managed their family home.

Mario went to elementary and primary school in Mexico. When he was 11, his parents sent him to a boarding school in Switzerland. There, he learned to speak German. Mario was at first a bit sad because his classmates did not share his strong interest in science.

Molina earned his first degree in chemical engineering in 1965. He studied at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). After that, he studied in Germany for two years. In 1968, he went to the University of California, Berkeley. He earned his Ph.D. in physical chemistry in 1973.

Career and Discoveries

After getting his Ph.D., Mario Molina joined a research program. He worked with Sherwood Rowland at UC Berkeley. Together, they studied special gases called Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Their work led to a huge discovery in atmospheric chemistry.

Understanding CFCs and the Ozone Layer

Rowland and Molina studied CFCs. These gases seemed harmless and were used in things like refrigerators, spray cans, and making plastic foams. They wondered: "What happens when we release something new into the environment?" This question led them to develop their theory about CFCs and ozone depletion.

Molina tried to figure out how CFCs could break down. He thought that ultraviolet light from the sun could break down CFCs. This light is known to break down oxygen molecules. If CFCs broke down, they would release chlorine atoms into the stratosphere. The stratosphere is a part of Earth's atmosphere.

Molina and Rowland predicted that these chlorine atoms would act like a catalyst. A catalyst speeds up a chemical reaction without being used up. They believed chlorine atoms would keep destroying ozone. Their theory made people realize the danger of CFCs. This led to efforts to reduce their use.

In 1985, a scientist named Joseph Farman found a hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica. Mario Molina then led a team to study why the ozone was disappearing so fast there. They found that the conditions in the Antarctic stratosphere were perfect for chlorine to become active. This active chlorine then caused the ozone to break down.

In 1995, Mario Molina shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He won it with Paul J. Crutzen and F. Sherwood Rowland. They received the award for their important work on CFCs and the ozone layer.

Between 1974 and 2004, Molina worked at several universities. These included the University of California, Irvine, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In 2004, he joined the University of California, San Diego. He also worked at the Center for Atmospheric Sciences.

Molina also advised U.S. President Barack Obama on environmental issues in 2008. He was part of the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. In 2020, he was part of a team of scientists. They stressed the importance of wearing masks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Personal Life and Death

Molina married Luisa Y. Tan, who was also a chemist, in July 1973. They met while he was studying at the University of California, Berkeley. They moved to Irvine, California that fall. Their son, Felipe Jose Molina, was born in 1977. They divorced in 2005. Luisa Tan Molina is now a lead scientist at a research center in La Jolla, California. Mario Molina married his second wife, Guadalupe Álvarez, in February 2006.

Mario Molina passed away on October 7, 2020. He was 77 years old and died from a heart attack.

Awards and Honors

Mario Molina received many awards for his scientific work:

- 1987: He won the Esselen Award from the American Chemical Society.

- 1988: He received the Newcomb Cleveland Prize.

- 1989: He won the NASA Medal for Exceptional Scientific Advancement. He also received the United Nations Environmental Program Global 500 Award.

- 1990: He was honored as one of ten environmental scientists. He received a grant from The Pew Charitable Trusts.

- 1995: He shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. This was for his discovery of how CFCs harm the ozone layer.

- 1996: He received the Golden Plate Award from the American Academy of Achievement.

- 1993: He was chosen to be a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences.

- 1996: He was also elected to the United States Institute of Medicine.

- 1998: He received the Willard Gibbs Award.

- 2003: He became a member of The National College of Mexico. He also received the Heinz Award in the Environment.

- 2007: He was elected to the American Philosophical Society. He was also a member of the Mexican Academy of Sciences.

- 2013: U.S. President Barack Obama gave Molina the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This is a very high honor.

- 2014: He received the Lifetime Achievement Award from Champions of the Earth.

Honorary Degrees

Mario Molina received more than thirty honorary degrees. These are special degrees given by universities to honor someone's achievements. Some of the universities that honored him include:

- Yale University (1997)

- Tufts University (2003)

- Duke University (2009)

- Harvard University (2012)

- Many universities in Mexico, the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

Mario Molina Quotes

- “Finding out for myself, for the first time, how something works is really an enormous driving force.”

- “Many Latino kids should become scientists because we need scientists all over the world from all different backgrounds.”

- “Climate change, like depletion of the ozone layer, is proof of the damage human activities exert on earth at the global level.”

Interesting Facts About Mario Molina

- Mario Molina became very interested in chemistry even before high school.

- As a child, he turned a bathroom in his home into his own small laboratory. He used toy microscopes and chemistry sets.

- His aunt, Ester Molina, was already a chemist. She helped him with more complex chemistry experiments.

- Mario first wanted to be a professional violinist. But his love for chemistry became stronger.

- During his career, Molina taught and did research at many top universities. These include the University of California, Irvine, California Institute of Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and University of California, San Diego.

- In 2005, Molina started the Mario Molina Center for Energy and Environment in Mexico City. He was its director.

- Molina advised the President of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto, on climate policy.

- He was one of twenty-two Nobel Laureates who signed the third Humanist Manifesto in 2003. This is a document about human values.

- An Asteroid (9680 Molina) is named after him.

- On March 19, 2023, Google honored Molina with a special Google Doodle in several countries.

See also

In Spanish: Mario Molina (químico) para niños

In Spanish: Mario Molina (químico) para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |