Max Perutz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

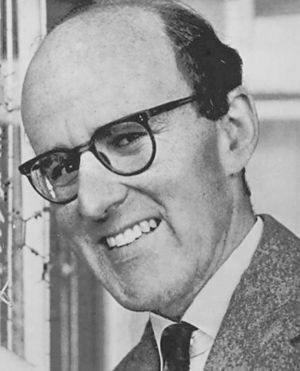

Max Perutz

|

|

|---|---|

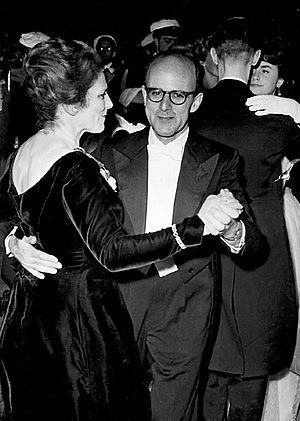

Perutz in 1962

|

|

| Born |

Max Ferdinand Perutz

19 May 1914 |

| Died | 6 February 2002 (aged 87) Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Heme-containing proteins |

| Spouse(s) | Gisela Clara Peiser (m. 1942; 2 children) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Molecular biology Crystallography |

| Institutions | University of Cambridge Laboratory of Molecular Biology |

| Doctoral advisor | John Desmond Bernal |

| Doctoral students |

|

Max Ferdinand Perutz (1914–2002) was a very important scientist. He was born in Austria but became British. He was a molecular biologist. In 1962, he won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. He shared it with John Kendrew. They won for their work on the structures of haemoglobin and myoglobin.

Perutz also won other big awards, like the Royal Medal in 1971 and the Copley Medal in 1979. At Cambridge, he started and led the Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB). Many scientists from the LMB have won Nobel Prizes.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Max Perutz was born in Vienna, Austria, on May 19, 1914. His parents were Adele and Hugo Perutz. His father made textiles. Max's family had a Jewish background, but he was baptized Catholic. Later in life, he did not follow any religion.

His parents wanted him to be a lawyer. But Max became very interested in chemistry while he was still in school. He convinced his parents and started studying chemistry at the University of Vienna. He finished his degree in 1936.

A teacher told him about new work in biochemistry at the University of Cambridge. Max wanted to go there. He was accepted as a research student by J. D. Bernal. Bernal wanted help with X-ray crystallography. Max didn't know much about it, but he learned quickly. He started studying the structure of proteins using X-rays. He focused on horse haemoglobin. This protein became a main focus of his work for many years. He earned his PhD under Lawrence Bragg.

Max joined Peterhouse college at Cambridge. He chose it because it had the best food! He was later made an Honorary Fellow of Peterhouse in 1962. He cared a lot about the students and often spoke at the college's science club.

World War II and Scientific Contributions

When Hitler took over Austria in 1938, Max's parents escaped to Switzerland. They lost all their money, so Max no longer had their financial help. Max was good at skiing and mountaineering. He used these skills to study how snow turns into ice in Swiss glaciers in 1938. His work made him known as an expert on glaciers.

Lawrence Bragg saw promise in Max's haemoglobin research. He helped Max get money from the Rockefeller Foundation in 1939. This money allowed Max to bring his parents to England.

When World War II started, Max was held for a few months because he was from Austria. He was sent to Newfoundland but later returned to Cambridge. Because of his glacier research, he was asked for advice on hiding soldiers under glaciers in Norway. This led him to a secret project called Project Habakkuk in 1942. The goal was to build a huge ice platform in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean to refuel planes. Max studied a special mix of ice and wood pulp called pykrete. He did his first experiments with pykrete in a secret place under Smithfield Meat Market in London.

Building the Molecular Biology Unit

After the war, Max briefly went back to studying glaciers. He showed how glaciers move.

In 1947, Max got support from the Medical Research Council (MRC). This allowed him to start the Molecular Biology Unit at the Cavendish Laboratory. This new unit attracted many smart scientists, like Francis Crick in 1949 and James D. Watson in 1951. They knew that studying molecules in biology was very important.

In 1953, Perutz found a way to figure out the structure of protein crystals using X-rays. He compared X-ray patterns from protein crystals with and without heavy atoms attached. In 1959, he used this method to find the exact structure of haemoglobin. Haemoglobin is the protein in blood that carries oxygen. This amazing work led to him sharing the 1962 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with John Kendrew. Today, scientists use X-ray crystallography to find the structures of thousands of proteins every year.

After 1959, Perutz and his team kept studying haemoglobin. In 1970, he explained how haemoglobin works like a tiny machine. He showed how it changes shape to pick up oxygen and then release it to muscles and other body parts. He also studied how changes in haemoglobin can cause diseases like sickle cell anaemia. In his later years, he studied how changes in protein structures are linked to diseases like Huntington disease.

DNA Structure and Rosalind Franklin

In the early 1950s, Watson and Crick were trying to figure out the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Perutz gave them a report from King's College that had not yet been published. This report included X-ray diffraction images taken by Rosalind Franklin. These images were very important in helping Watson and Crick discover the double-helix structure of DNA.

Perutz shared the report without Franklin knowing or giving permission. She had not yet published her detailed analysis of the report. Perutz later said that the report did not contain anything Franklin had not already talked about in a lecture. He also said the report was meant to help different research groups funded by the MRC share information.

Max Perutz as a Writer

Later in his life, Perutz often wrote reviews and essays for The New York Review of Books. Many of these essays are in his 1998 book, I wish I had made you angry earlier. In 1985, he also wrote about his experiences during World War II as a person held by the government.

Max's writing skills developed later in life. His relative, Leo Perutz, who was a famous writer, once told Max he would never be a writer. But Max proved him wrong with his excellent letters and essays. He even won the Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science in 1997.

The Scientist and Citizen

Perutz had strong opinions about science and society. He disagreed with some ideas from philosophers Sir Karl Popper and Thomas Kuhn. He also disagreed with biologist Richard Dawkins when Dawkins attacked religion. Perutz believed that scientists should not offend people's religious beliefs. He thought such actions could harm science's reputation. He felt it was different from criticizing false ideas like creationism. He said that "even if we do not believe in God, we should try to live as though we did."

After the attacks on September 11, 2001, Perutz wrote to British Prime Minister Tony Blair. He asked Blair not to respond with military force. He was worried that revenge would lead to more innocent deaths and a cycle of terror. He hoped Blair could help prevent this.

Awards and Recognition

Max Perutz received many honors for his scientific work. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1954. Besides the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1962, he was also made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1963.

Other important awards include:

- Austrian Decoration for Science and Art (1967)

- Royal Medal (1971)

- Companion of Honour (1975)

- Copley Medal (1979)

- Order of Merit (1988)

He also received honorary doctorates and was a member of several important scientific academies around the world. The European Crystallographic Association created the Max Perutz Prize in his honor.

Books by Max Perutz

Max Perutz wrote several books about science:

- Proteins and Nucleic Acids: Structure and Function (1962)

- Is Science Necessary? Essays on science and scientists (1989)

- Mechanisms of Cooperativity and Allosteric Regulation in Proteins (1990)

- Protein Structure : New Approaches to Disease and Therapy (1992)

- Science is Not a Quiet Life : Unravelling the Atomic Mechanism of Haemoglobin (1997)

- I Wish I’d Made You Angry Earlier (2002)

- What a Time I Am Having: Selected Letters of Max Perutz (2009)

Personal Life

In 1942, Max Perutz married Gisela Clara Mathilde Peiser (1915–2005). She was a medical photographer. They had two children: Vivien (born 1944), who became an art historian, and Robin (born 1949), who became a chemistry professor. Gisela was a refugee from Germany.

Max Perutz died on February 6, 2002. His ashes were buried with his parents in Cambridge. Gisela died in 2005, and her ashes were buried in the same grave.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Max Perutz para niños

In Spanish: Max Perutz para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |