Moons of Uranus facts for kids

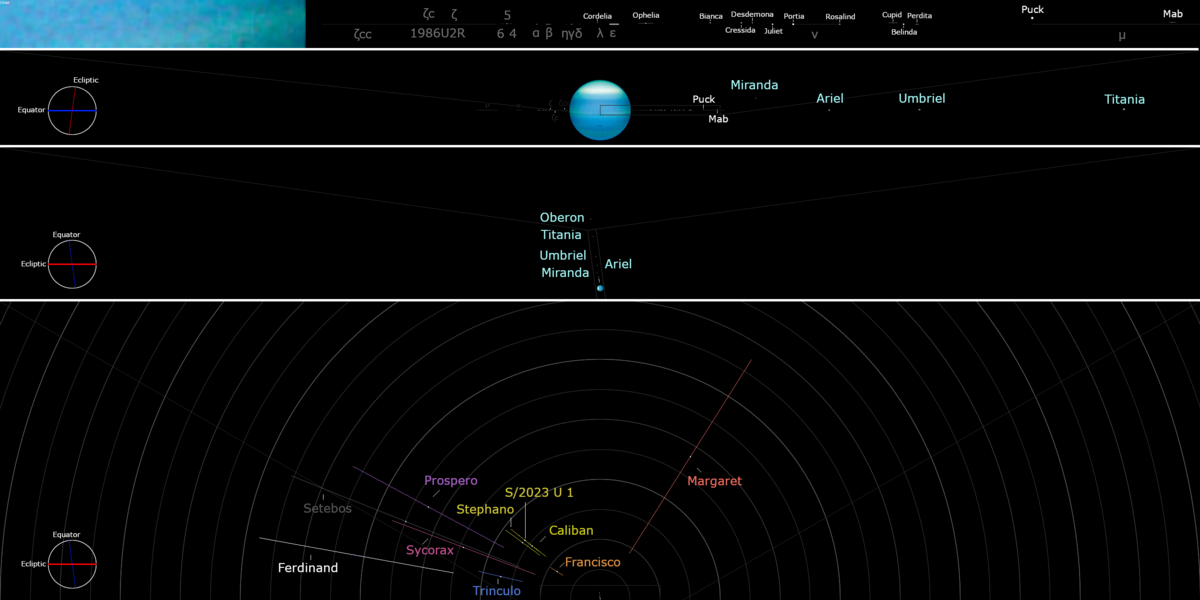

Uranus, the seventh planet from the Sun, has 28 known moons. Most of these moons are named after characters from plays by William Shakespeare and poems by Alexander Pope. Uranus's moons are split into three main groups: thirteen inner moons, five large moons, and ten irregular moons. The inner and large moons all orbit Uranus in the same direction as the planet spins. These are called regular moons. The irregular moons, however, orbit much farther away, have very tilted paths, and most of them orbit backwards compared to Uranus's spin.

The inner moons are small and dark. They are similar to Uranus's rings and likely formed from pieces of a broken moon. The five large moons are roundish, meaning their own gravity has pulled them into a spherical shape. Four of these large moons show signs of activity from inside, like the creation of canyons and volcanoes on their surfaces. The biggest of these five, Titania, is 1,578 kilometers (about 980 miles) wide. It's the eighth-largest moon in our Solar System, but it's still much smaller than Earth's Moon. The regular moons orbit almost exactly in the same flat plane as Uranus's equator, which is tilted a lot (97.77 degrees) compared to its orbit around the Sun. Uranus's irregular moons have oval-shaped and very tilted orbits, mostly backwards, and are very far from the planet.

William Herschel discovered the first two moons, Titania and Oberon, in 1787. The other three roundish moons were found later: Ariel and Umbriel in 1851 by William Lassell, and Miranda in 1948 by Gerard Kuiper. These five moons are big enough to be considered dwarf planets if they orbited the Sun directly. The rest of Uranus's moons were discovered after 1985, either by the Voyager 2 spacecraft or with powerful telescopes on Earth.

Contents

Discovering Uranus's Moons

The first two moons found were Titania and Oberon. Sir William Herschel spotted them on January 11, 1787, six years after he discovered Uranus itself. For almost 50 years, only Herschel's telescope was powerful enough to see these moons.

In the 1840s, better telescopes and a clearer view of Uranus in the sky led to more discoveries. The next two moons, Ariel and Umbriel, were found by William Lassell in 1851. In 1852, Herschel's son, John Herschel, gave these four moons their names.

No other moons were found for almost another century. In 1948, Gerard Kuiper at the McDonald Observatory discovered Miranda, the smallest of the five large, round moons.

Decades later, the Voyager 2 space probe flew past Uranus in January 1986. This mission led to the discovery of ten more inner moons. Another moon, Perdita, was found in 1999 by studying old Voyager photos.

Uranus was the last giant planet without any known irregular moons until 1997. That year, astronomers using telescopes on Earth discovered Sycorax and Caliban. From 1999 to 2003, astronomers kept looking for irregular moons of Uranus with even stronger telescopes. This led to the discovery of seven more irregular moons. In addition, two small inner moons, Cupid and Mab, were found using the Hubble Space Telescope in 2003. More recently, in 2021 and 2023, Scott Sheppard and his team discovered one more irregular moon using the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii.

Moon Groups and Features

Uranus's moon system is the least massive among the giant planets. In fact, all five of Uranus's large moons combined weigh less than half of Triton, which is Neptune's largest moon. The biggest of Uranus's moons, Titania, has a radius of about 789 kilometers (490 miles). This is less than half the size of Earth's Moon, but slightly bigger than Rhea, Saturn's second-largest moon. This makes Titania the eighth-largest moon in our Solar System. Uranus itself is about 10,000 times heavier than all its moons put together.

Inner Moons

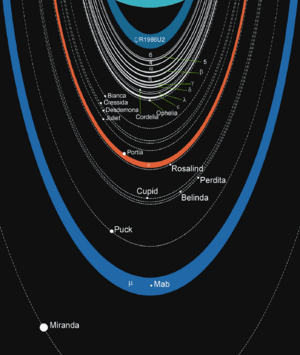

Uranus has 13 inner moons, all of which orbit closer to the planet than Miranda. These inner moons are grouped by how far they orbit. The Portia group includes six moons: Bianca, Cressida, Desdemona, Juliet, Portia, and Rosalind. The Belinda group has three moons: Cupid, Belinda, and Perdita.

All the inner moons are closely linked to the rings of Uranus. The rings likely formed from pieces of one or more small inner moons that broke apart. The two innermost moons, Cordelia and Ophelia, act as "shepherd moons" for Uranus's epsilon ring, helping to keep it in place. The small moon Mab is the source of Uranus's outermost mu ring.

At 162 kilometers (101 miles) wide, Puck is the largest of Uranus's inner moons. It's also the only inner moon that Voyager 2 photographed in detail. Puck and Mab are the two farthest inner moons from Uranus. All inner moons are dark, reflecting less than 10% of the sunlight that hits them. They are made of water ice mixed with a dark, carbon-rich material that has been changed by radiation.

These inner moons constantly pull on each other, especially within the tightly packed Portia and Belinda groups. This system is quite unstable. Computer models show that the moons might eventually pull each other into paths that cross, which could lead to collisions. For example, Desdemona might crash into Cressida within the next million years. Cupid will likely collide with Belinda in the next 10 million years. Because of this, the rings and inner moons might be constantly changing, with moons crashing and reforming over short periods of time.

Large Moons

Uranus has five large moons: Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon. Their sizes range from 472 kilometers (293 miles) for Miranda to 1578 kilometers (980 miles) for Titania. These moons are fairly dark, reflecting between 30% and 50% of sunlight. Umbriel is the darkest, and Ariel is the brightest. Their weights vary from 6.7 million billion kilograms (Miranda) to 350 million billion kilograms (Titania). For comparison, Earth's Moon weighs about 7500 million billion kilograms.

Scientists believe Uranus's large moons formed from a disk of gas and dust that surrounded Uranus after it formed. Another idea is that they formed from a huge impact that Uranus experienced early in its history. This idea is supported by how well they hold heat, similar to dwarf planets like Pluto and Haumea. This is different from Uranus's irregular moons, suggesting they formed in a different way.

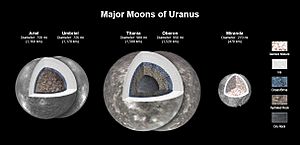

All the large moons are made of about half rock and half ice, except for Miranda, which is mostly ice. The ice might contain ammonia and carbon dioxide. Their surfaces are covered in many craters. However, all of them (except Umbriel) show signs of activity from inside. This activity created features like long canyons and, on Miranda, oval-shaped structures called coronae. These coronae likely formed from blobs of material rising up from inside the moon. Ariel seems to have the youngest surface with the fewest impact craters, while Umbriel's surface looks the oldest.

Scientists think that past gravitational tugs between Miranda and Umbriel, and between Ariel and Titania, caused heating inside these moons. This heating led to the significant internal activity seen on Miranda and Ariel. One clue for this past interaction is Miranda's unusually tilted orbit (4.34 degrees) for a moon so close to its planet.

The largest Uranian moons likely have layers inside them, with rocky centers surrounded by icy layers. Titania and Oberon might even have oceans of liquid water deep inside, between their rocky centers and icy layers. The large moons of Uranus have no atmosphere. For example, Titania has almost no air around it.

The way the Sun moves across the sky on Uranus and its large moons during their summer is very different from Earth. The large moons have almost the same tilt as Uranus itself. During the summer in one hemisphere, the Sun would appear to move in a circle around the point in the sky directly above Uranus's pole, never setting. Near the equator, the Sun would appear almost due north or south, depending on the season.

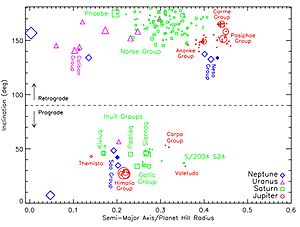

Irregular Moons

Uranus's irregular moons vary in size, from Sycorax (120–200 kilometers wide) to S/2023 U 1 (less than 10 kilometers wide). Since only a few Uranian irregular moons are known, it's not yet clear which ones belong to groups with similar orbits. The only known group among Uranus's irregular moons is the Caliban group. These moons orbit between 6 and 7 million kilometers from Uranus and have orbital tilts between 141 and 144 degrees. The Caliban group includes three moons that orbit backwards: Caliban, S/2023 U 1, and Stephano.

There are no known moons with orbital tilts between 60 and 140 degrees. This is because of something called the Kozai instability. In this region, the Sun's gravity pulls on the moons in a way that makes their orbits very oval-shaped. This can cause them to crash into inner moons or even be thrown out of Uranus's system. Moons in this unstable region only last from 10 million to a billion years. Margaret is the only known irregular moon of Uranus that orbits in the same direction as the planet, and it has one of the most oval-shaped orbits of any moon in the Solar System.

List of Uranus's Moons

Here is a list of Uranus's moons, ordered from the fastest orbit to the slowest. Moons that are large enough to be pulled into a round shape by their own gravity are shown in light blue and bold. The inner and large moons all orbit in the same direction as Uranus spins. Irregular moons that orbit backwards are shown in dark grey. Margaret, the only known irregular moon of Uranus that orbits forwards, is shown in light grey.

The orbits and average distances of the irregular moons can change quite a bit over short periods because the Sun and other planets constantly pull on them. So, the orbital details listed for irregular moons are averages from a long computer simulation. These might be different from other lists that show their current orbital paths. Recently discovered irregular moons without published average orbital details are temporarily listed with their current orbital paths, shown in italic to tell them apart. All orbital details are based on January 1, 2000.

| Key | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner moons |

♠ Large moons |

† Ungrouped forward-orbiting irregular moons |

‡ Ungrouped backward-orbiting irregular moons |

♦ Caliban group |

| Label |

Name | How to say it (key) |

Image | Brightness | Diameter (km) |

Mass (× 1016 kg) |

Semi-major axis (km) |

Orbital period (d) |

Orbit Tilt (°) |

Orbit Shape |

Discovery year |

Year announced | Discoverer |

Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VI | Cordelia | 10.3 | 40 ± 6 (50 × 36) |

≈ 4.4 | 49770 | +0.33503 | 0.08479° | 0.00026 | 1986 | 1986 | Terrile (Voyager 2) |

ε ring shepherd | ||

| VII | Ophelia |  |

10.2 | 43 ± 8 (54 × 38) |

≈ 5.3 | 53790 | +0.37640 | 0.1036° | 0.00992 | 1986 | 1986 | Terrile (Voyager 2) |

ε ring shepherd | |

| VIII | Bianca |  |

9.8 | 51 ± 4 (64 × 46) |

≈ 9.2 | 59170 | +0.43458 | 0.193° | 0.00092 | 1986 | 1986 | Smith (Voyager 2) |

Portia | |

| IX | Cressida | 8.9 | 80 ± 4 (92 × 74) |

≈ 34 | 61780 | +0.46357 | 0.006° | 0.00036 | 1986 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) |

Portia | ||

| X | Desdemona | 9.3 | 64 ± 8 (90 × 54) |

≈ 18 | 62680 | +0.47365 | 0.11125° | 0.00013 | 1986 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) |

Portia | ||

| XI | Juliet |  |

8.5 | 94 ± 8 (150 × 74) |

≈ 56 | 64350 | +0.49307 | 0.065° | 0.00066 | 1986 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) |

Portia | |

| XII | Portia | 7.7 | 135 ± 8 (156 × 126) |

≈ 170 | 66090 | +0.51320 | 0.059° | 0.00005 | 1986 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) |

Portia | ||

| XIII | Rosalind | 9.1 | 72 ± 12 | ≈ 25 | 69940 | +0.55846 | 0.279° | 0.00011 | 1986 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) |

Portia | ||

| XXVII | Cupid | 12.6 | ≈ 18 | ≈ 0.38 | 74800 | +0.61800 | 0.100° | 0.0013 | 2003 | 2003 | Showalter and Lissauer |

Belinda | ||

| XIV | Belinda | 8.8 | 90 ± 16 (128 × 64) |

≈ 49 | 75260 | +0.62353 | 0.031° | 0.00007 | 1986 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) |

Belinda | ||

| XXV | Perdita | 11.0 | 30 ± 6 | ≈ 1.8 | 76400 | +0.63800 | 0.0° | 0.0012 | 1999 | 1999 | Karkoschka (Voyager 2) |

Belinda | ||

| XV | Puck | 7.3 | 162 ± 4 | ≈ 290 | 86010 | +0.76183 | 0.3192° | 0.00012 | 1985 | 1986 | Synnott (Voyager 2) |

|||

| XXVI | Mab | 12.1 | ≈ 18 | ≈ 0.38 | 97700 | +0.92300 | 0.1335° | 0.0025 | 2003 | 2003 | Showalter and Lissauer |

μ ring source | ||

| V | Miranda♠ | 3.5 | 471.6 ± 1.4 (481 × 468 × 466) |

6400±300 | 129390 | +1.41348 | 4.232° | 0.0013 | 1948 | 1948 | Kuiper | |||

| I | Ariel♠ | 1.0 | 1157.8±1.2 (1162 × 1156 × 1155) |

125100±2100 | 191020 | +2.52038 | 0.260° | 0.0012 | 1851 | 1851 | Lassell | |||

| II | Umbriel♠ | 1.7 | 1169.4±5.6 | 127500±2800 | 266300 | +4.14418 | 0.205° | 0.0039 | 1851 | 1851 | Lassell | |||

| III | Titania♠ | 0.8 | 1576.8±1.2 | 340000±6100 | 435910 | +8.70587 | 0.340° | 0.0011 | 1787 | 1787 | Herschel | |||

| IV | Oberon♠ | 1.0 | 1522.8±5.2 | 307600±8700 | 583520 | +13.4632 | 0.058° | 0.0014 | 1787 | 1787 | Herschel | |||

| XXII | Francisco‡ | 12.4 | ≈ 22 | ≈ 0.72 | 4282900 | −267.09 | 147.250° | 0.1324 | 2001 | 2003 | Holman et al. | |||

| XVI | Caliban♦ |  |

9.1 | 42+20 −12 |

≈ 25 | 7231100 | −579.73 | 141.529° | 0.1812 | 1997 | 1997 | Gladman et al. | Caliban | |

| S/2023 U 1♦ | 13.7 | ≈ 8 | ≈ 0.034 | 7978000 | −680.76 | 141.893° | 0.1867 | 2023 | 2024 | Sheppard et al. | Caliban | |||

| XX | Stephano♦ |  |

9.7 | ≈ 32 | ≈ 2.2 | 8007400 | −677.47 | 143.819° | 0.2248 | 1999 | 1999 | Gladman et al. | Caliban | |

| XXI | Trinculo‡ | 12.7 | ≈ 18 | ≈ 0.39 | 8505200 | −749.40 | 166.971° | 0.2194 | 2001 | 2002 | Holman et al. | |||

| XVII | Sycorax‡ |  |

7.4 | 157+23 −15 |

≈ 230 | 12179400 | −1288.38 | 159.420° | 0.5219 | 1997 | 1997 | Nicholson et al. | ||

| XXIII | Margaret† | 12.7 | ≈ 20 | ≈ 0.54 | 14146700 | +1661.00 | 57.367° | 0.6772 | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard and Jewitt |

|||

| XVIII | Prospero‡ |  |

10.5 | ≈ 50 | ≈ 8.5 | 16276800 | −1978.37 | 151.830° | 0.4445 | 1999 | 1999 | Holman et al. | ||

| XIX | Setebos‡ |  |

10.7 | ≈ 48 | ≈ 7.5 | 17420400 | −2225.08 | 158.235° | 0.5908 | 1999 | 1999 | Kavelaars et al. | ||

| XXIV | Ferdinand‡ | 12.5 | ≈ 12 | ≈ 0.54 | 20430000 | −2790.03 | 169.793° | 0.3993 | 2001 | 2003 | Holman et al. |

See also

In Spanish: Satélites de Urano para niños

In Spanish: Satélites de Urano para niños