Moses Schorr facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Moses Schorr

|

|

|---|---|

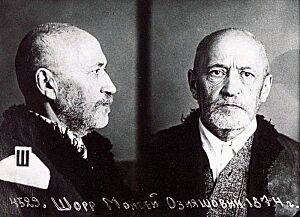

Moses Schorr, ca. 1921

|

|

| Born | May 10, 1874 Przemyśl, Galicia and Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary

|

| Died | July 8, 1941 (aged 67) Posty, Uzbek SSR, Soviet Union

|

| Nationality | Polish |

| Other names | Mojżesz Schorr |

| Occupation | Rabbi, scholar, activist |

| Known for | Senator of the 2nd Republic of Poland |

Moses Schorr (born May 10, 1874 – died July 8, 1941) was a very important person in Polish history. He was a rabbi (a Jewish religious leader), a historian, and a politician. He also studied the Bible and ancient languages.

Schorr was one of the best experts on the history of the Jews in Poland. He was the first Jewish researcher to study old Polish records and Jewish community books called pinkasim. He was a modern rabbi who led the main synagogue in Poland before World War II. He was also a humanist, meaning he believed in human values and dignity.

Moses Schorr was the first historian to really study Jewish history in Poland, especially in a region called Galicia. He made exciting discoveries by finding and translating old laws from Babylon, Assyria, and Hittite civilizations. He was an expert on the laws and cultures of the Ancient Middle East.

Later, the Polish president, Ignacy Mościcki, chose Schorr to be a Senator in the Polish government. Schorr didn't belong to any political party, but he supported Zionism, which is the idea of a Jewish homeland. He was very active in helping Polish Jews and often represented them to leaders in Poland and other countries.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Moses Schorr was born on May 10, 1874, in a town called Przemyśl. This town was in a region called Galicia, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire at the time.

Moses was the oldest son of Osjasz Schorr, who managed a Jewish bank. His mother was Esther Schorr. He had two younger brothers, Adolf and Samuel, who both became lawyers. Moses went to a school called a gymnasium in Przemyśl and finished in 1893. There, and from his family, he learned a lot about Jewish traditions and history.

Studying to Become a Rabbi

After school, Schorr moved to Vienna in 1893. He studied theology at the Jewish Theological Institute until 1900. This institute trained students to become rabbis. He also studied philosophy at the University of Vienna and Lwów University from 1893 to 1898.

While studying in Vienna, Schorr learned Hebrew and other ancient languages. He was especially interested in Egyptian history and culture. In 1898, he earned his Doctor of Philosophy degree. In 1900, he officially became a rabbi in Vienna.

Teaching in Lwów

Soon after becoming a rabbi, Schorr started teaching in Lwów (now Lviv). He taught at the Jewish Teachers Seminary and a teachers' school until 1923. He also did a lot of work helping the community.

Schorr was very passionate about studying ancient languages and cultures. He wrote to a friend that he wished he had more time for his studies. He felt pulled between his teaching job and his love for learning about the ancient world. He also became very involved in community activities, like popular meetings and committees.

Studying Ancient Languages

Schorr received a special scholarship from the Austrian government. He used it to study in Berlin for two years. There, he focused on Semitic languages (like Hebrew and Arabic), Assyriology (the study of ancient Assyria), and the history of the ancient Middle East. He learned from famous scholars.

From 1905 to 1906, he studied Arabic in Vienna. His teacher, David Heinrich Müller, greatly influenced him. Müller taught him how to analyze the Bible and study Semitic languages.

Professor and Community Leader

In 1904, Schorr became a lecturer at Lwów University. By 1910, he was an associate professor of Semitic languages and ancient Middle Eastern history. He later held a similar position in Warsaw.

He was very active in the Jewish community in Lwów. He led a society that promoted education among Jews. He also helped start and lead "Opieka" (meaning "Care"), a group that supported Jewish high school students. Schorr also helped found the "Society of the teachers of Moses religion," which was for Jewish teachers. He was also a leader of the Jewish Community Library in Lwów.

Schorr and Zionism

In 1910, Schorr attended the 7th Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. This meeting made a big impression on him. He wrote that it showed how strong Jewish people around the world were together. He saw it as a powerful sign of Jewish unity.

Schorr married Tamara Ben Jacob in 1905. Her father was a wealthy banker and a strong supporter of Zionism.

Becoming a Full Professor

In 1916, Schorr became a full professor at Lwów University. He continued to teach Semitic languages and ancient Middle Eastern history until 1923. He also attended international meetings of experts on ancient cultures. In 1912, he gave a lecture in Athens about ancient Babylonian law.

During World War I, from 1917 to 1918, he led the Jewish Rescue Committee in Lwów. He also helped Jewish orphans in the city. In 1919, he became the first head of the Society of Jewish National and Secondary schools.

Moving to Warsaw

In 1923, Moses Schorr moved to Warsaw, the capital of Poland. He was invited to become the main preacher at the Great Synagogue, Warsaw. This synagogue was huge, seating 1,100 people. It was the largest synagogue in Europe at the time. Warsaw had a very large Jewish community, with over 350,000 Jews in 1931.

Schorr also joined the Warsaw rabbinical council, which was a very important Jewish religious authority in Poland. He was chosen as an inter-regional rabbi, meaning he represented the Jewish community to the government. He also became a member of school councils.

In 1924, he became the head of the committee that tested Jewish teachers of religion. He also helped review school textbooks on Jewish subjects.

Warsaw University and Jewish Studies

In 1926, Schorr became a professor at the University of Warsaw. He led the Institute of Semitic languages and ancient Middle Eastern history there. In 1927, he helped create the Jewish Library at the Great Synagogue in Warsaw, which was finished in 1936. Today, this building houses the Jewish Historical Institute.

Institute of Judaic Sciences

In 1928, Schorr helped start the Institute of Judaic Sciences in Warsaw. This institute was for studying Jewish history, philosophy, religion, and languages. It had a large library with over 35,000 books. Professor Schorr was the first leader (rector) of this new institute from 1928-1930 and again from 1933-1934.

In 1933, he became a member of the Polish Academy of Sciences. In 1937, he received an honorary doctorate from the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York.

Schorr and B'nai B'rith

From 1901, Schorr was a member of B'nai B'rith, a humanitarian society. He led the library for their "Leopolis" branch in Lwów for several years. This group helped people and promoted good values.

In 1924, he became the president of the "Braterstwo" (Brotherhood) lodge in Warsaw. This group had many important members, including doctors, engineers, and even other senators. Schorr organized many cultural events and initiatives through this lodge. He helped create an organization to build a Jewish Academic House in Warsaw. He also supported the Institute of Judaic Sciences and a Jewish magazine called Miesięcznik Żydowski.

Schorr's group also did a lot of charity work. Wealthy members donated large sums of money to help those in need, especially Jewish victims of the economic crisis.

In 1937-1938, the Polish government banned many societies, including B'nai B'rith.

Schorr believed that B'nai B'rith had two main goals:

- To unite all Jewish people around the world.

- To promote the idea of brotherhood among all people and nations.

He helped create another B'nai B'rith lodge in Łódź, which was the second-largest Jewish community in Poland. Schorr also wrote about the difficult situation of Jews in Germany after 1933. He wanted to combine Jewish unity with the idea of universal brotherhood.

Schorr's Political Life

Moses Schorr mostly focused on his scientific work, teaching, and community activities. However, in 1935, the president of Poland, Ignacy Mościcki, appointed him as a Senator in the Polish parliament.

In his speeches and articles, Schorr often spoke about the rise of antisemitism (hatred against Jewish people) in Poland. He was concerned that the authorities were not doing enough to stop it. He also led a committee that tried to help Jews immigrate from Poland to other countries, not just Palestine.

He participated in the Évian Conference in France in 1938. This conference was called by US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to discuss the problem of Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria. Schorr was a key speaker there, as many Jews were fleeing to Poland.

Last Years and Death

When World War II began, Schorr knew he was in danger from the Nazis because he was a prominent Jewish leader. On September 6 or 7, 1939, he and his wife, Tamara, fled Warsaw and went east. They reached the town of Ostróg on September 27, where his daughter Felicia lived.

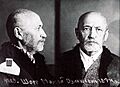

Arrest and Imprisonment

The Soviet secret police (NKVD) quickly noticed Schorr in Ostróg. Two days after he arrived, they arrested him. He was held in local prisons for a couple of weeks before being moved to Lwów, where he had lived before.

In prison, Schorr had to answer many questions. He was asked when and why he became a Senator and a rabbi, and which political party he belonged to. He explained that the president appointed him as a Senator because he was the Rabbi of Warsaw, and that he didn't belong to any party.

On February 3, 1941, Schorr was sent to Lubyanka Prison in Moscow. He shared a cell with other important Polish figures, including a poet and another Senator. One cellmate described how Schorr, despite his age, was often taken for harsh questioning and beaten. Even so, he remained calm and dignified. He even became friends with a Polish nationalist leader in the cell, and they shared a bed.

Attempts to Free Him

The Polish government-in-exile and the Vatican tried to get Schorr released, but they were unsuccessful. In February 1940, the US Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, also asked the Soviet authorities to find and free Schorr, but it didn't work. The Polish Prime Minister, Władysław Sikorski, also wrote a letter asking for his release.

Death in a Camp

On April 17, 1941, Schorr was sentenced to five years of forced labor. He was sent to a Soviet concentration camp in Posty, Uzbekistan. He became ill there and died in the camp hospital on July 8, 1941. He was buried in the hospital grounds.

Polish authorities learned of his death only in late 1941 or early 1942. They had been trying to free him again, hoping to make him the main Rabbi of the Anders Army, a Polish army forming in the Soviet Union, but it was too late.

Schorr's Family

Moses Schorr married Tamara Ben Jacob in 1905. Her father was a publisher, Zionist, and banker. They had six children:

- Sonia, who married a prosecutor. She died in 1961.

- Deborah, who died young in 1917.

- Felicia Kon-Lipets, who died in New York City in 1984.

- Ludwig (1918–1963), an architect who lived in Tel Aviv.

- Esther, who died in Jerusalem in 1991.

- Joshua (Otton), an engineer who died in Jerusalem in 2005.

Awards and Legacy

Moses Schorr received Poland's Golden Cross of Merit award. His name is on a memorial near the Polish Parliament that honors Senators who died because of the NKVD (Soviet secret police) or the Nazis.

In 1993, a scientific meeting was held in Kraków to honor Schorr. In 2001, an Educational Center named after Professor Moses Schorr was opened in Warsaw. This center helps teach Jewish culture and history to Jewish people in Poland. It was founded by the Ronald Lauder Foundation.

Streets Named After Schorr

There are streets named after Moses Schorr in three cities in Israel: Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Holon.

Schorr's Scientific Work

One of Schorr's main areas of study was the history of Polish Jews. He believed that to truly understand this history, researchers needed to study specific cities and use original documents from archives. He thought that general histories were not accurate enough without this detailed research.

He started his scientific work in 1897 with a paper about Don Joseph Nasi, an influential Jewish figure in the 16th century. Schorr analyzed Nasi's relationship with the Polish king. Even as a young student, Schorr found new information that corrected mistakes made by other famous historians. He discovered that Joseph Nasi was looking for trade benefits for himself in Lwów, not just helping Polish diplomacy.

Selected Publications by M. Schorr

- Schorr, M. Prof Dr. M. Schorr at the new place of work. Chwila, 18 November 1923.

- Schorr, M. Jewish question at the time of the Great Seim. Chwila, 13–24 July 1920.

- Schorr, M. Palestine and Babylon in the light of new archeological excavations. Chwila, 27, 28, 30 January 1922; 1–6 February 1922.

- Schorr, M. Moses' Law in comparative perspective with the legislatures of the Ancient Middle East: Assyrian, Babylonian and Hittite. Chwila, 3-7, 13, 17, 19-22, 24–29 November 1923.

- Schorr, M. History of Jews in Przemyśl. Vienna: Verlag von R. Lövit, 1915.

- Schorr, M. Jews in Przemyśl until the end of the 18th century. Lwów, 1903.

- Schorr, M. Monument of Old Assyrian Law of 12th century B.C. Lwów: Archiwum Towarzystwa Naukowego we Lwowie, 1922.

- Schorr, M. Problem of the Hittites due to the newest linguistic-historical discovery. in Kwartalnik Historyczny, Lwów, 1916.

- Schorr, M. Babylonian and Hebrew culture. Lwów, 1903.

- Schorr, M. Babylonian state and society in times of Hammurabi dynasty of 2500 - 2000 B.C. Lwów: Drukarnia Ludowa, 1906.

- Schorr, M. Organisation of Jews in Poland since the earliest times till 1772. Kwartalnik Historyczny (1899).

- Schorr M. Inaugurative speech presented at the Great Tlomacka Synagogue on 2.12.1923. Warsaw: Druk. Kupenztocha i Kramaria, 1923.

- Schorr M. Hammurabi Code and the Ancient Middle Eastern legal practice. Cracow, 1907.

- Schorr, M. The Important Issues on the History of the Semitic Orient. Lwów: Druk. Związkowa, 1907.

- Schorr, M. Biblical Antiquities in the Light of Egyptian Archive of 17th century B.C. Lwów: Druk. Związkowa, 1901.

- Schorr, M. The trade movement in the Ancient Babylon. in "Księga pamiątkowa ku uczczeniu zaŀożenia Uniw. Lwowskiego", Lwów, 1911.

- Schorr, M. Documents of Old Babylonian civil and criminal law. Leipzig: Vor der Asiatischen Bibliothek, 1913.

- Schorr, M. Concerning the history of Don Joseph Nasi. in Monatschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judenthums, 1897.

- Schorr, M. Cracow Collection of Jewish statutes and privileges. in Evreyskaya Starina, 1909.

- Schorr, M. Main privileges of Polish Jewry. in "Festschrift Adolf Schwartz zu siebzigsten Geburtstage 15. Juli 1916", Berlin – Vienna, 1917.

- Schorr, M. Legal status and internal constitution of Jews in Poland – A historical overview. in "Der Jude", 1917.

- Schorr, M. State Seer and State Teacher – A Contribution to the Biography of Theodor Herzl. in Festschrift zu Simon Dubnows siebzigsten Geburtstag, Berlin, 1930.

- Schorr, M. Prof Dr Majer Balaban – on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of his birth. in Nasz Przegląd 21.2.1937.

- Schorr, M. Ideals of the Order B'nai B'rith and their application in real life conditions. Typescript. Archiwum Państwowy w Krakowie / Polish State Archives in Cracow, B'nai B'rith 351.

Images for kids