First Nagorno-Karabakh War facts for kids

The First Nagorno-Karabakh War was a conflict that took place from February 1988 to May 1994. It was fought over Nagorno-Karabakh, a small area in southwestern Azerbaijan. The main groups involved were ethnic Armenians living in Nagorno-Karabakh, supported by Armenia, and the country of Azerbaijan.

The roots of the war go back to 1918. After World War I, the Ottoman Empire broke apart. New independent countries like Armenia and Azerbaijan were formed. Nagorno-Karabakh was recognized as part of Azerbaijan. However, Armenia claimed the region. Armenians tried to unite the area with Armenia. Azerbaijanis worked to protect their sovereignty and national identity.

The war officially began in February 1988. Both sides used their governments to support their claims. Sadly, there were also violent attacks and killings against each other. Both sides lost and gained land at different times. The Soviet Union, before it broke up in 1991, and later Russia, also got involved. This involvement affected how the war played out. More than 30,000 people died on both sides during the war.

Many countries tried to help stop the fighting. These included Moscow, European nations, neighboring countries, the United Nations, and the United States. But they had different goals, and Nagorno-Karabakh was not their top priority.

The war finally ended with a ceasefire arranged by Russia. This agreement started at midnight on May 11 and 12, 1994. It lasted until April 2, 2016.

Contents

How the War Started

In 1918, after World War I, Armenia and Azerbaijan became independent. Both countries claimed Nagorno-Karabakh. At the Versailles Peace Conference, the region was given to the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic of 1918-1920. In the early 1920s, the Soviet Union took over these countries. The Soviet government decided that Nagorno-Karabakh would stay part of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1923, the region was given special self-governing status as the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast.

Armenians living in Nagorno-Karabakh said they faced unfair treatment from Azerbaijanis. They also felt the region was neglected. However, the area actually had a good living standard compared to other mountain regions in the Soviet Union.

On February 13, 1988, Armenians from Karabakh held a protest in Yerevan. Hundreds of people joined. They called for Nagorno-Karabakh to join Armenia. They chanted "Unity!" in Armenian ("Miatsum!"). This event made Azerbaijanis in Nagorno-Karabakh angry. About 25% of the region's population was Azerbaijani. In Shusha, a town near Stepanakert where 90% of people were Azerbaijani, counter-protests began.

A week later, on February 20, 1988, the local government of Nagorno-Karabakh held an emergency meeting. They voted to place the region under Armenian control. 110 Armenian officials voted for this, while Azerbaijani officials did not vote.

Both the Azerbaijan Soviet Republic and the Soviet Union itself criticized this decision. The Soviet Union worried that other regions might also want to break away. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev did not want to give in to any demands for territory. He sent a large group to Nagorno-Karabakh to try and fix the situation.

Armenian Efforts for Unity

Armenians had tried for a long time to unite Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia. They sent letters and requests to Moscow. In 1988, these efforts became very strong. Many Armenians from outside Nagorno-Karabakh helped organize these campaigns.

One organizer, Igor Muradyan, brought a letter to Moscow in 1986. He got nine Armenian scientists and Communist Party members to sign it. They also tried to get rid of Heidar Aliev, an Azerbaijani politician who they thought would stop their plans.

Armenian activists also worked with an illegal nationalist group called the Dashnaktsutiun Party. This group helped them get weapons and form small armed groups in Nagorno-Karabakh.

To make their campaign seem official, activists gathered signatures for a "referendum" (a public vote) on unification. By August 1987, they had over 75,000 signatures from people in the region and Armenia. They sent this petition to Moscow.

Some Armenians also tried to get support from other countries. For example, in November 1987, Abel Aganbekian, an economic adviser to Gorbachev, told French Armenians in Paris that Nagorno-Karabakh had "greater links with Armenia than with Azerbaijan." This made many Azerbaijanis think that Gorbachev supported Armenians, which was not true.

Even though Armenian activists did not get support from Gorbachev, they managed to get many people to protest. On February 20, 1988, 30,000 people protested in Yerevan. Two days later, over 100,000 people joined. By February 25, almost a million people were demonstrating in Yerevan.

Azerbaijani Responses

Azerbaijanis did not ignore these Armenian actions. Their own nationalist movement became more organized. Seven days after the Armenian protest began, Azerbaijanis held their first protest. Students, workers, and thinkers marched in front of the Supreme Soviet of the Azerbaijan SSR. They carried signs saying Nagorno-Karabakh was part of Azerbaijan. They felt Armenians were trying to harm their country and identity.

Azerbaijani historians also spoke out. They wrote in a journal that Nagorno-Karabakh had always been part of Azerbaijan. They said Armenian efforts were based on wanting more land. They argued that Azerbaijanis were the victims. However, these arguments did not reach Moscow.

War Begins

On February 22, two days after the Nagorno-Karabakh government voted to join Armenia, protests happened in Aghdam. Angry protesters marched towards Stepanakert. On their way, they clashed with police and Armenian villagers in Askeran.

The situation got worse after February 20, 1988. Azerbaijanis living in the Kafan District in southern Armenia started to flee. Many were hurt from beatings and fights. They rushed to their relatives in Baku.

Six days after the Nagorno-Karabakh government's decision, a group of Azerbaijanis protested in Sumgait. The next day, hundreds joined the protest. In the evening, violence broke out. The local police, mostly Azerbaijani, did not stop the violence.

The protest in Sumgait turned into violent attacks against Armenians. Rioters searched for Armenians to attack. They destroyed property, stole valuable items, and set cars on fire.

The situation in Sumgait calmed down on February 29. The Soviet Union sent soldiers and put a curfew in place. By the end of that day, 32 people were officially reported dead: 26 Armenians and 6 Azerbaijanis. Over 400 people were arrested. Almost all 14,000 Armenians living in Sumgait left. Thousands of Armenians across Azerbaijan also fled their homes.

War Gets Worse

Gorbachev and the Soviet government tried to get Armenia and Azerbaijan to agree on Nagorno-Karabakh. But all their efforts failed. In May 1988, the Armenian leader in Nagorno-Karabakh rejected a plan. This plan would have given the region special status as an Autonomous Republic with its own government. But it would still remain part of Azerbaijan.

Then, on June 15, the Armenian parliament voted to approve the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh. Two days later, the Azerbaijani parliament said the region was part of their country. The local government in Stepanakert then decided to join Armenia on its own. It renamed the region the Artsakh Armenian Autonomous Region. However, on July 18, the Soviet Union's parliament in Moscow said that Nagorno-Karabakh was still part of Azerbaijan. Both Azerbaijan and Gorbachev rejected the idea of unification.

By the end of 1988, all Azerbaijanis remaining in Armenia were forced to leave. In the Armenian countryside, dozens of villages were left empty. Armenian groups attacked Azerbaijani villages, burning houses. Many residents had to escape on foot.

Fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh

Armenians made up about 75% of the population in Nagorno-Karabakh. They protested against Azerbaijanis with their large numbers. Armenians attacked buses and trucks bringing goods to Shusha. In Stepanakert, Azerbaijani workers were fired. They even stopped Azerbaijani shepherds from bringing sheep back from their summer grazing lands.

Azerbaijanis used the fact that Nagorno-Karabakh was inside their territory. They blocked the transport of goods to Stepanakert. This caused shortages.

In September 1988, near Khojaly, Azerbaijani people attacked a group of Soviet soldiers and Armenian civilians transporting goods. Two Soviet soldiers died. In response, armed Armenians attacked the village. As a result, the few Armenians in Shusha left. Azerbaijani residents in Stepanakert were also forced out.

In the summer of 1989, Azerbaijanis went further. They blocked all railways to Armenia. Almost 90% of Armenia's railway supplies came from Azerbaijan. This blockade caused a lack of petrol and food in Armenia.

In January 1989, a Soviet committee banned political activities in Nagorno-Karabakh. They sent military troops to keep order. However, on August 16, Armenians there formed a National Council. It declared that it was controlling Nagorno-Karabakh. The Armenian parliament, along with this National Council, confirmed the region's unification with Armenia. They also gave residents Armenian citizenship.

Black January Events

Despite being rejected by Azerbaijan and the Soviet Union, Armenia started to set up its own government structures in Nagorno-Karabakh. On January 9, 1990, the Armenian parliament decided to control the region's budget. This angered Azerbaijanis. Both sides fought in villages in the Khanlar and Shaumian regions. Four Russian soldiers died.

On January 13, violence against Armenians happened in Baku. About 90 Armenians died during these attacks. Thousands of Armenians fled the city. Facing this chaos, Gorbachev ordered the army to Baku on the night of January 19 and 20. During this time, many people in Baku were killed. This event is known as Black January.

War Becomes International

On August 19, 1991, there was a coup d'état (a sudden takeover of power) in Moscow. Gorbachev was temporarily removed from power. Three days later, he got his power back. But this political chaos weakened the Soviet army in Nagorno-Karabakh.

This chaos also helped Armenia and Azerbaijan move closer to independence from the Soviet Union. On August 30, 1991, Azerbaijan declared its independence. On September 21, Armenia held a public vote, and 95% of its citizens supported independence.

Before, the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh was an internal issue for the Soviet Union. After Armenia and Azerbaijan became independent, it became a dispute between two separate countries. On September 2, 1991, the local government in Stepanakert declared Nagorno-Karabakh independent as the Nagorno Karabakh Republic.

As the situation worsened, neighboring countries tried to arrange a peace agreement. In September 1991, Boris Yeltsin of Russia and Nursultan Nazarbayev, the President of Kazakhstan, visited Stepanakert. They adopted the Zheleznovodsk declaration for peace. However, on November 20, a helicopter carrying Azerbaijani, Russian, and Kazakh officials was shot down by Armenian fighters. All on board were killed. In response, the Azerbaijani National Council declared on November 26 that Nagorno-Karabakh was under Azerbaijani control. They also renamed Stepanakert to Khankendi. Despite this, Armenians in the region held a vote on December 10. 108,615 people voted for independence. No Azerbaijanis voted.

Final Stage of the War

In August 1993, Serzh Sarkisian from Nagorno-Karabakh became Armenia's Defense Minister. This brought more Armenian soldiers from both the region and Armenia into the fight. Azerbaijan, on the other hand, gathered about 2,500 Afghan fighters.

In December, the fighting became very intense again. During the winter of late 1993 and early 1994, about 4,000 Azerbaijanis and 2,000 Armenians were killed. Azerbaijan only managed to regain small parts of its territory in the north and south of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Ceasefire Agreement

On May 4 and 5, 1994, officials from countries in the CIS, including Armenia and Azerbaijan, met in Bishkek. A representative from Nagorno-Karabakh was also invited. There, the Bishkek Protocol was signed by the Russian envoy and the Armenians. This agreement called for a ceasefire to start at midnight on May 8 and 9. However, the Azerbaijani delegation did not sign it right away. They needed approval from Heidar Aliev, who was then the President of Azerbaijan.

Finally, on May 9, Mamedrafi Mamedov, Azerbaijan's Defense Minister, signed the protocol. The next day, his Armenian counterpart, Sarkisian, signed it in Yerevan. On May 11, Samvel Babayan, the Karabakh Armenian commander, agreed in Stepanakert. The ceasefire officially began at midnight on May 11 and 12, 1994.

Images for kids

-

Internally displaced Azerbaijanis from Nagorno-Karabakh, 1993.

-

Ruins of Agdam in 2009

-

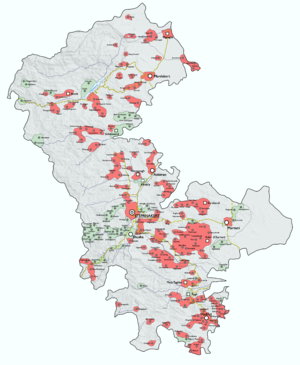

The final borders of the conflict after the 1994 ceasefire was signed. Armenian forces of Nagorno-Karabakh currently control almost 9% of Azerbaijan's territory outside the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast. Azerbaijani forces, on the other hand, control Shahumian and the eastern parts of Martakert and Martuni.

-

The graves of Armenian soldiers in Stepanakert.

-

Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan visiting Nagorno-Karabakh, 13 November 2010

-

Ilham Aliyev, Serzh Sargsyan and Vladimir Putin, 10 August 2014

See also

In Spanish: Primera guerra del Alto Karabaj para niños

In Spanish: Primera guerra del Alto Karabaj para niños