Shusha facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

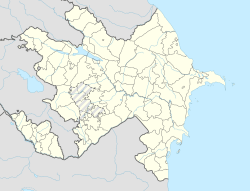

Shusha / Shushi

|

|

|---|---|

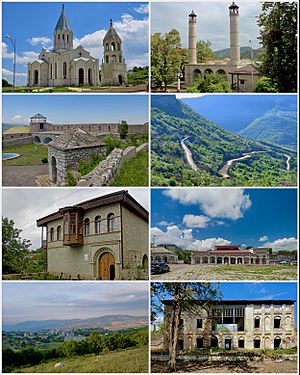

Landmarks of Shusha, from top left:

Ghazanchetsots Cathedral • Yukhari Govhar Agha Mosque Shusha fortress • Shusha mountains House of Mehmandarovs • City center Shusha skyline • House of Khurshidbanu Natavan |

|

| Country | |

| Region | Karabakh |

| District | Shusha |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.5 km2 (2.1 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,800 m (5,900 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 1,400 m (4,600 ft) |

| Population

(2015)

|

|

| • Total | 4,064 |

| Demonym(s) | Şuşalı ("Shushaly"; in Azerbaijani ) Շուշեցի ("Shushets'i"; in Armenian) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (AZT) |

| ISO 3166 code | AZ-SUS |

| Vehicle registration | 58 AZ |

Shusha (also known as Shushi) is a city in Azerbaijan. It is located in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. The city sits high in the Karabakh mountains, between 1,400 and 1,800 meters (4,600–5,900 feet) above sea level. In the past, during the Soviet era, it was a popular mountain resort.

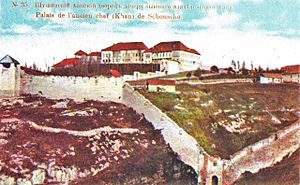

Many people believe Shusha was founded in the 1750s. Panah Ali Khan, who started the Karabakh Khanate, built the Shusha fortress around this time. Some stories say he worked with Melik Shahnazar II, a local Armenian prince. They say the city's name came from a nearby Armenian village called Shosh or Shushikent. However, other sources suggest Shusha was already an important Armenian center in the 1720s. Some even say there was an Armenian fort on the plateau before then.

From the mid-1700s to 1822, Shusha was the capital of the Karabakh Khanate. After Russia took control of the South Caucasus in the early 1800s, Shusha became a major cultural hub. It grew into a city, home to many Armenian and Azerbaijani thinkers, poets, writers, and musicians.

Shusha is important to both Armenians and Azerbaijanis for its history, culture, and location. Many Azerbaijanis see it as the birthplace of their music and poetry. It is a leading center of Azerbaijani culture. Shusha also has several Armenian Apostolic churches, like Ghazanchetsots Cathedral and Kanach Zham. It connects Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia through the Lachin corridor. For a long time, the city had a mixed Armenian and Azerbaijani population. Early records from 1823 show more Azerbaijanis lived there. Over time, the Armenian population grew and became the majority. But in 1920, the Armenian part of the city was destroyed, and many Armenians were killed or forced to leave.

The city has faced a lot of damage and lost many people during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. In 1992, Armenian forces took control of Shusha during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. Most of the Azerbaijani people living there fled, and much of the city was destroyed. From 1992 to 2020, Shusha was controlled by the Republic of Artsakh. On November 8, 2020, Azerbaijani forces took the city back after a three-day battle. The Armenian population then fled. There have been reports of damage to Armenian cultural sites. In 2022, the Azerbaijani government opened the city to tourists from Azerbaijan. They plan to help people resettle there in 2023.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Many historians think the name Shusha comes from the Persian word Shīsha, which means "glass" or "bottle." One story says that when an Iranian ruler named Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar came to the town, he told the ruler of Karabakh, "God is pouring stones on your head. Don't sit in your fortress of glass."

Another name for Shusha was Panahabad, which means "City of Panah." This name honored Panah Ali Khan, who was the first ruler of the Karabakh Khanate.

Some believe the name Shusha comes from a nearby village called Shushikent (or Shosh in Armenian). This name means "Shusha village" in Azerbaijani. However, an Armenian historian named Leo thought the village might have been named after the fortress, which he believed was older.

Armenian sources suggest the name Shusha likely comes from the Armenian word shosh or shush. This word means "tree sprout" or, more generally, a "high place." It might have first been used for the nearby village or for Shusha itself.

Over time, Shusha has had other Armenian names too, like Shoshi Berd or Shoshvaghala. These names all mean "Shosh/Shushi Fortress."

Shusha's Long History

Early Beginnings

Some Armenian historians connect Shusha to an old fortress called Shikakar or Karaglukh. They say an Armenian prince won a battle against an Arab army there in the 800s. Other sources say a settlement called Shosh was an ancient fort in the Armenian area of Varanda. This fort belonged to the Melik-Shahnazarian princely family.

Some records suggest that Shushi existed and had a place for writing books in 1428. The fortress was important for Armenian forces fighting against Ottoman armies in the 1720s and 1730s. An Armenian historian, Ashot Hovhannisian, believed the fortress walls were built by an Armenian commander in 1724 or even earlier.

In 1725, an Armenian activist described Shusha as both a town and a fort. He wrote that armed Armenians guarded it. He also mentioned that Armenians had won battles against the Turks in Karabakh.

In 1769, the Georgian king Heraclius II wrote that an "ancient fortress" in Karabakh was taken by a Muslim man from the Javanshir tribe. Russian military leader Alexander Suvorov also mentioned this ancient fortress. He wrote that the Armenian prince Melik Shahnazar gave his fortress, Shushikala, to a leader of nomadic Muslims named Panah Ali Khan. Another Russian historian, P. G. Butkov, wrote that the "Shushi village" was given to Panah Ali Khan by the Melik-Shahnazarian prince after they became allies. Panah Ali Khan then made the village stronger.

Other sources, including several Azerbaijani historians, say that Panah Ali Khan founded the town between 1750 and 1752 (or 1756–1757). He was the first ruler of the Karabakh Khanate.

According to one history book, the Karabakh nobles decided to build a strong fort in the mountains to protect against invaders. Melik Shahnazar of Varanda, who supported Panah Ali Khan, suggested the location. This is how Panahabad-Shusha was founded.

Before Panah Ali Khan built the fortress, the area was used for farming and grazing by people from the nearby Shoshi village. Panah Khan moved people from other villages to Shusha and built strong walls.

An Armenian novelist, Raffi, also wrote that the area where Shushi was built was empty before Panah Ali Khan arrived. He stated that Panah-Ali Khan and Melik-Shahnazar finished building the fortress in 1762. They then moved the Armenian people from the nearby Shosh village into the new fortress.

Battles with the Qajars

Soon after Shusha was founded, the Karabakh Khanate was attacked by Mohammad Hassan Khan Qajar, a powerful leader from Iran. He wanted to reclaim Karabakh, which his family had ruled before.

Mohammad Hassan Khan surrounded Shusha, but he had to leave quickly because another leader, Karim Khan Zand, attacked his own land. He left his cannons behind. Panah Ali Khan then attacked Mohammad Hassan Khan's retreating army.

In 1756 (or 1759), Shusha was attacked again by Fath-Ali Khan Afshar, another Iranian ruler. He had a large army and some local support. The siege of Shusha lasted for six months, but Fath-Ali Khan eventually had to leave.

Later, when Karim Khan Zand became the ruler of Iran, he made Panah Ali Khan come to Shiraz. Panah Ali Khan died there as a hostage. His son, Ibrahim Khalil Khan, was sent back to Karabakh as governor. Under him, the Karabakh Khanate grew stronger, and Shusha became a larger city. Travelers in the late 1700s and early 1800s said Shusha had about 2,000 houses and 10,000 people.

In 1795, Shusha faced a big attack from Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar. He wanted to unite Iran and take back the Caucasus region. Shusha was the first major challenge.

Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar surrounded Shusha with a large army. Ibrahim Khalil Khan prepared the city for a long defense. About 15,000 people, including women, fought to protect Shusha. Armenians in Karabakh also helped, fighting alongside the Muslim population.

The siege lasted 33 days. Agha Mohammad Khan could not capture Shusha, so he moved on to Tbilisi, which he attacked. Ibrahim Khalil Khan eventually surrendered to Mohammad Khan after talks. He agreed to pay tribute and give hostages, but the Qajar forces were not allowed into Shusha.

In 1797, Agha Mohammad Shah Qajar attacked Karabakh again. He destroyed villages near Shusha. The city was still recovering from the 1795 attack and also suffered from a long drought. The attackers' cannons caused a lot of damage. So, in 1797, Agha Mohammad Shah took Shusha, and Ibrahim Khalil Khan had to flee.

However, a few days later, Agha Mohammad Khan was killed by his bodyguards in Shusha. Ibrahim Khalil Khan returned to the city. To keep peace with Iran, he gave his daughter to the new shah as one of his wives.

Under Russian Rule

In the early 1800s, Russia wanted to expand its territory in the Caucasus. After taking Georgia in 1801, some local leaders agreed to become Russian protectorates. In 1804, Russia invaded Iran, starting a war. During this war, in 1805, the Karabakh Khanate agreed to join Russia. However, Russia did not fully control Karabakh yet.

Russia fully took control of the Karabakh Khanate after the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813. Iran had to give up Karabakh and other areas in the Caucasus to Russia. This was confirmed again after another war in 1828 with the Treaty of Turkmenchay.

During the 1826–1828 war, Shusha's fort held out for several months and was never captured. After this, Shusha was no longer a capital of a khanate. Instead, it became an administrative center for the Karabakh province. Shusha grew, and many people moved there, especially Armenians, who became the majority in the surrounding mountains.

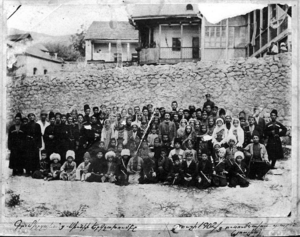

By the 1830s, the town was split into two parts. Turkic-speaking Muslims lived in the eastern, lower areas. Armenian Christians settled in the newer, western, upper areas. The Muslim part had seventeen neighborhoods, each with its own mosque, bathhouse, and leader. The Armenian part had 12 neighborhoods, five churches, and schools.

People in Shusha mainly traded, raised horses, wove carpets, and made wine. Shusha was also the biggest center for silk production in the Caucasus. Many Muslim people in Shusha and Karabakh raised sheep and horses. They moved between mountain pastures in summer and lowland pastures in winter.

In the 1800s, Shusha was one of the largest and richest cities in the Caucasus. It was even bigger than Baku or Yerevan. It was a hub for trade routes, with ten inns for travelers. It was famous for its silk, paved roads, colorful carpets, stone houses, and fine horses. In 1824, a visitor named George Keppel found two thousand houses in the town. He noted that three-quarters of the people were Azerbaijanis and one-quarter were Armenian. He also said that Armenians did most of the trade.

Early 1900s

The early 1900s saw the first conflicts between Armenians and Azerbaijanis in the region. This happened for two reasons. First, there was growing tension between local Muslims and Armenians, whose numbers had increased due to Russian policies. Second, people in the Caucasus started seeking more control over their culture and land. Political problems in Russia, like the 1905 and 1917 Revolutions, turned these movements into national freedom movements.

The first clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis happened in Baku in February 1905. The conflict then spread to other parts of the Caucasus. On August 5, 1905, the first conflict in Shusha took place. Hundreds of people died, and over 200 houses were burned.

After World War I and the fall of the Russian Empire, Azerbaijan claimed Karabakh as part of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Armenia and the Armenian people in Karabakh strongly disagreed, saying Karabakh was part of Armenia. In October 1918, Turkish troops entered Shusha. Armenians in Shusha did not fight them to avoid violence. After the Ottoman Empire lost World War I, Armenian forces defeated Azerbaijani forces and headed towards Shusha. British troops then told the Armenian commander to stop, as they wanted the region's future to be decided at a peace conference. The British put an Azerbaijani governor in charge of Karabakh for a while.

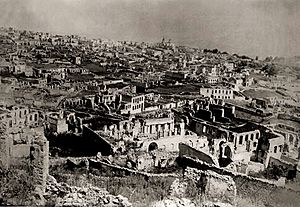

Conflicts between ethnic groups continued. In June 1919, about 600 Armenian villagers near Shusha were killed by Azerbaijani and Kurdish groups. In August 1919, the Karabakh National Council had to agree to Azerbaijani rule until the peace conference decided the issue. However, the Azerbaijani government often broke this agreement. The governor used harsh methods like terror and blockades. In February 1920, he demanded that Armenians accept joining Azerbaijan. He then killed people in several Armenian villages. This led to an Armenian uprising, which the Azerbaijani army stopped. In March 1920, a British journalist reported that the Armenian police in Shusha killed the Azerbaijani police during their holiday. This attack led to the massacre and expulsion of the Armenian population in March 1920. Between 500 and 20,000 Armenians were killed, others fled, and the Armenian part of the city was destroyed.

Soviet Times

In 1920, the Soviet Red Army invaded Azerbaijan and Armenia. The conflict over Karabakh then became a diplomatic issue. To gain Armenian support, the Soviets promised to give disputed lands, including Karabakh, to Armenia. However, in July 1921, the Communist Party decided that Karabakh would stay within Azerbaijan. It would become an autonomous region with Shusha as its center. As a result, the Mountainous Karabakh Autonomous Region was created in 1923. A few years later, Stepanakert became the new capital of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast and its largest town.

Many believe that Joseph Stalin made the decision to keep Nagorno-Karabakh within Azerbaijan. He was in charge of nationalities at the time. He may have done this to keep Moscow in control between the Armenian and Azerbaijani Soviet republics.

The town of Shusha remained mostly in ruins until the 1960s. Then, it slowly began to recover because of its potential as a resort. In 1977, the Shusha State Historical and Architectural Reserve was created. The town became a major resort in the former USSR.

The Armenian quarter remained in ruins until the early 1960s. In 1961, the government decided to clear away many of the ruins. Three Armenian churches and one Russian church were torn down. The Armenian part of the town was rebuilt with simple buildings common in that era.

Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

1988–1994 War

When the First Nagorno-Karabakh War began in 1988, Shusha became a very important Azerbaijani stronghold. From Shusha, Azerbaijani forces often shelled Stepanakert, causing many Armenian civilian deaths and great damage. On May 9, 1992, Armenian forces captured the town. The Azerbaijani population fled. An Armenian commander said that Armenian citizens from Stepanakert looted and burned the city. They had suffered months of bombing from Azerbaijani forces. He also mentioned a local belief of burning houses to prevent the enemy from returning. A British journalist saw Armenian soldiers using mosque minarets as targets. By 2002, ten years after the city was captured, about 80% of Shusha was in ruins. Armenians also took and sold old bronze statues of three Azerbaijani musicians and poets from Shusha. Another journalist reported that gravestones in the Azerbaijani cemetery were "methodically smashed and vandalised."

After the war, Armenians, mostly refugees from Azerbaijan and other parts of Karabakh, moved into Shusha. The city's population was much smaller than before the war. It changed from mostly Azerbaijani to completely Armenian. The main highway connecting Goris and Stepanakert passed through Shusha, making it a stop for travelers. There were some hotels, and cultural sites like the Ghazanchetsots Cathedral and the Yukhari Govhar Agha Mosque were restored by Armenian authorities.

After the war, a tank that had been hit during the city's capture was placed as a memorial. It was removed by Azerbaijani authorities in September 2023 and moved to a park in Baku.

2020 War

During the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Armenia accused the Azerbaijani army of shelling civilian areas and the Ghazanchetsots Cathedral. Three journalists were hurt while filming inside the cathedral after an earlier shelling. The Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence denied shelling the church. The House of Culture was also badly damaged.

On November 8, 2020, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev announced that the Azerbaijani army had taken control of Shusha. The next day, the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence released a video confirming their full control. Artsakh authorities also confirmed they had lost control. A ceasefire signed two days later meant the city stayed under Azerbaijani control. The Armenian government and church later claimed that Azerbaijani soldiers damaged Armenian churches and cultural sites. Azerbaijani officials claimed that a mosque and fountain were damaged by Armenian forces.

Shusha's Culture and Arts

Shusha has important cultural sites for both Armenians and Azerbaijanis. The areas around it also have many old Armenian villages.

Shusha is often called the birthplace of Azerbaijani music and poetry. It is a main center of Azerbaijani culture. In January 2021, it was named the cultural capital of Azerbaijan. The city is famous for its traditional Azerbaijani singing style called mugham. For Azerbaijanis, Shusha is like the "conservatory of the Caucasus." Many famous Azerbaijani artists were born here, including poet Khurshidbanu Natavan, composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov, and singer Bulbul. A famous Azerbaijani poet, Molla Panah Vagif, lived and died in Shusha. Poetry events in his honor have been held in Shusha since 1982 and restarted in 2021.

Shusha is also a historic Armenian religious and cultural center. The Armenian people living there had four main churches. These included Ghazanchetsots Cathedral (also called Holy Savior Cathedral) and Kanach Zham. Shusha also had a monastery. In 1989, Ghazanchetsots Cathedral became the main church for the Armenian Diocese of Artsakh.

Shusha is important in the history of Armenian music. Composer Grikor Suni and his choir were based there. Suni helped create the national identity of Armenian music. The Khandamirian or Shushi theater, opened in 1891, was famous for its contributions to Armenian arts, especially music. Suni gave his first performance there. By 1902, Suni's group performed a big concert in Shusha. They later traveled the world, sharing Armenian cultural music. Shusha was also the hometown of Arev Baghdasaryan, a famous Armenian singer and dancer.

Shusha is also known for its sileh rugs, which are floor coverings from the South Caucasus.

In November 2020, the organizers of the Turkvision Song Contest said they might hold their 2021 contest in Shusha. In January 2021, the Azerbaijani Ministry of Culture began preparing for the Khari Bulbul Music Festival and Vagif Poetry Days.

Museums in Shusha

During the Soviet period, Shusha had several museums. These included the Shusha Museum of History, the house museum of composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov, the house museum of singer Bulbul, and the Shusha Carpet Museum. The Azerbaijan State Museum of History of Karabakh was founded in Shusha in 1991, just before the war.

When the city was under Armenian control, it had several museums. These included the State Museum of Fine Arts, the G. A. Gabrielyants State Geological Museum, the Shushi History Museum, the Shushi Carpet Museum, and the Shushi Art Gallery.

The Shushi History Museum is in a 19th-century mansion. It has items related to Shusha's history, from ancient times to modern days. The museum has many local crafts, household items, and photos showing life in 19th-century Shusha. There are also sections about the 1920 Shusha Massacre and the capture of Shusha by Armenian forces in 1992. The G. A. Gabrielyants State Geological Museum opened in 2014. It has 480 samples of rocks and fossils from 47 countries.

When Azerbaijani forces took Shusha in 2020, most museum collections were left behind. Only the rugs from the Shushi Carpet Museum were removed.

In August 2021, satellite images showed that 51 sculptures from the Museum of Fine Arts park were removed. The area was completely cleared. A group called Caucasus Heritage Watch expressed concern about these artworks. They asked Azerbaijani authorities to say where the sculptures are and if people can see them.

Who Lived in Shusha?

| Year | Armenians | Azerbaijanis | Others | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1823 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 1830 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 1851 |

|

||||||

| 1885 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 1886 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1897 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1904 |

|

|

|

||||

| 1908 | 37,591 | ||||||

| 1910 | 39,413 | ||||||

| 1914 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1916 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| March 1920: Massacre and expulsion of Armenian population by Azerbaijan | |||||||

| 1921 | 289 | 3.1% | 8,894 | 96.4% | 40 | 0.4% | 9,223 |

| 1923 | 209 | 3.0% | 6,682 | 95.9% | 74 | 1.1% | 6,965 |

| 1926 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1931 | 5,291 | ||||||

| 1939 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1959 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1970 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1979 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| September 1988: Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: Expulsion of Armenian population | |||||||

| 1989 |

|

||||||

| May 1992: Capture by Armenian forces. Expulsion of Azerbaijani population | |||||||

| 2005 |

|

|

|

||||

| 2009 |

|

|

|

||||

| 2015 |

|

|

|

||||

| November 2020: Capture by Azerbaijani forces. Exodus of Armenian population | |||||||

| 2024 | At least

|

|

At least

|

||||

The first Russian census in 1823 showed that Shusha had 1,111 (72.5%) Muslim families and 421 (27.5%) Armenian families. Seven years later, in 1830, the number of Muslim families dropped to 963 (55.8%). The number of Armenian families increased to 762 (44.2%).

George Keppel, who visited Karabakh in 1824, wrote that Shusha had two thousand houses. He noted that three-quarters of the people were "Tartars" (Azerbaijanis) and the rest were Armenians.

A survey from 1823 showed that all Armenians in Karabakh lived in the highland part. They were the clear majority in the five traditional Armenian areas. The survey recorded 57 Armenian villages and seven Tatar villages in these areas.

The 1800s brought changes to the population mix. After wars and Russia taking control, many Muslim families moved to Iran. Many Armenians moved to Shusha.

In 1851, Shusha's population was 15,194. By 1885, it grew to 30,000, and in 1910, it was 39,413.

By the late 1880s, the percentage of Muslims in the Shusha district decreased to 41.5%. The Armenian population increased to 58.2% in 1886.

By the second half of the 1800s, Shusha was the largest town in the Karabakh region. However, after the attack on the Armenian population in 1920 and the burning of the town, many people left. The city also became less important economically compared to other cities like Yerevan and Baku. Shusha became a small town of about 10,000 people. Its population kept dropping, reaching 5,104 by 1926. Armenians did not start returning until after World War II. The Armenian quarter only began to be rebuilt in the 1960s.

According to the last census in 1989, Shusha town had 17,000 people. The Shusha district had 23,000 people. Most of the population in both the district and the town (over 90%) was Azerbaijani.

After Armenian forces captured Shusha in 1992, the Azerbaijani population of 15,000 people was killed or forced to leave. Before the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, Shusha had over 4,000 Armenians. Most were refugees from Baku and other parts of Karabakh and Azerbaijan. Because of the first war, no Azerbaijanis live in Shusha today. However, Azerbaijani authorities plan to bring back Azerbaijanis who fled during the first war. Shusha's Armenian population fled just before the city was taken back by Azerbaijani forces in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War.

Economy and Tourism

When Shusha was under Armenian control, groups like the Shushi Revival Fund and the ArmeniaFund worked to improve the city's economy. They invested in tourism, leading to the opening of several hotels. A tourist information office was also opened. The two remaining Armenian churches were renovated. Schools, museums, and an arts institute also opened.

After taking back the town, Azerbaijani authorities renovated and opened the Khari Bulbul and Karabakh hotels. In August 2021, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev laid the foundation for a new hotel and conference center in Shusha.

Sister Cities

Famous People from Shusha

- Ibrahim Khalil Khan (1732-1806), Azerbaijani leader of the Karabakh Khanate.

- Gasim bey Zakir (1784–1857), Azerbaijani poet.

- Jafargulu agha Javanshir (1787–1867), Azerbaijani poet and Russian army general.

- Abbasqoli Mo'tamad-dawla Javanshir (1804-1862), Azerbaijani statesman and first justice minister of Iran.

- Karbalayi Safikhan Karabakhi (1820–1879), Azerbaijani architect.

- Ivan Davidovich Lazarev (1820–1879), Armenian lieutenant-general in the Russian army.

- Usta Gambar Karabakhi (1830–1905), Azerbaijani ornamental painter.

- Khurshidbanu Natavan (1832–1897), famous Azerbaijani poet.

- Sadigjan (1846–1902), Azerbaijani musician.

- Muratsan (1854–1908), Armenian writer.

- Karim bey Mehmandarov (1854-1929), Azerbaijani doctor, founded a girls' school.

- Amanullah Mirza Qajar (1857–1937), Iranian prince and military figure.

- Leo (1860–1932), Armenian historian.

- Stepan Aghajanian (1863–1940), Armenian painter.

- Hambardzum Arakelian (1865–1918), Armenian journalist.

- Alexander Atabekian (1868–1933), Armenian anarchist.

- Ahmet Ağaoğlu (1869–1939), Azerbaijani politician and journalist.

- Abdurrahim bey Hagverdiyev (1870–1933), Azerbaijani playwright and director.

- Feyzullah Mirza Qajar (1872–1920), Iranian prince and military figure.

- Suleyman Sani Akhundov (1875–1939), Azerbaijani playwright and journalist.

- Vartan Sarkisov (1875–1955), Soviet-Armenian architect.

- Freidun Aghalyan (1876–1944), Armenian architect.

- Tuman Tumanian (1879–1906), Armenian freedom fighter.

- Zulfugar Hajibeyov (1884–1950), Soviet-Azerbaijani composer.

- Ahmed Agdamski (1884–1954), Soviet-Azerbaijani opera singer.

- Arsen Terteryan (1882–1953), Soviet-Armenian scientist.

- Artashes Babalian (1886–1959), Armenian politician.

- Sahak Ter-Gabrielyan (1886–1937), Soviet-Armenian statesman.

- Hayk Gyulikekhvyan (1886–1951), Armenian literary critic.

- Ashot Hovhannisyan (1887–1972), Soviet-Armenian statesman and historian.

- Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminli (1887–1943), Soviet-Azerbaijani writer.

- Nariman bey Narimanbeyov (1889–1937), Azerbaijani lawyer and statesman.

- Mikael Arutchian (1897–1961), Soviet-Armenian painter.

- Bulbul (1897–1961), Soviet-Azerbaijani opera singer.

- Ivan Tevosian (1902–1958), Soviet-Armenian statesman.

- Khan Shushinski (1901–1979), Azerbaijani folk singer.

- Süreyya Ağaoğlu (1903–1989), Turkish writer and first female lawyer.

- Ivan Knunyants (1906–1990), Soviet-Armenian chemist.

- Latif Karimov (1906–1991), Azerbaijani carpet designer.

- Gevork Kotiantz (1909–1996), Soviet-Armenian painter.

- Shamsi Badalbeyli (1911–1987), Soviet-Azerbaijani actor and director.

- Nelson Stepanyan (1913–1944), Soviet-Armenian pilot.

- Barat Shakinskaya (1914–1999), Soviet-Azerbaijani actress.

- Gurgen Boryan (1915–1971), Soviet-Armenian poet and playwright.

- Soltan Hajibeyov (1919–1974), Soviet-Azerbaijani composer.

- Seyran Ohanyan (born 1962), Armenian politician and military commander.

- Abdulla Beg Velizade (1841-1912), poet

See also

In Spanish: Shusha para niños

In Spanish: Shusha para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |