Alexander Atabekian facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Atabekian

|

|

|---|---|

| Ալեքսանդր Աթաբեկյան | |

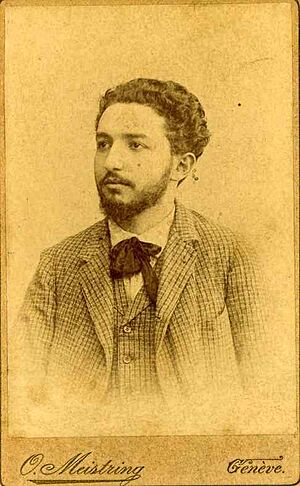

Atabekian (1890s)

|

|

| Born | 2 February 1869 Shushi, Elizavetpol, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 5 December 1933 (aged 64) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union

|

| Nationality | Armenian |

| Education | University of Geneva |

| Occupation | |

| Years active | 1889—1925 |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Political party | Social Democrat Hunchakian Party (1889–1890) Armenian Revolutionary Federation (1890–1896) |

| Movement | Armenian national movement, anarchist communism |

| Spouse(s) |

Ekaterina Nikolaevna Sokolova

(m. 1894; died 1922) |

| Children | 3 |

| Family | Atabekian |

Alexander Movsesi Atabekian (Armenian: Ալեքսանդր Մովսեսի Աթաբեկյան; born February 2, 1869 – died December 5, 1933) was an Armenian doctor, publisher, and a supporter of anarchist communism. This is a political idea where people believe in a society without a government or bosses, where everyone works together freely.

He was born in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. He later moved to Switzerland to study medicine at the University of Geneva. While there, he learned about publishing by working on a newspaper called Hunchak. In 1890, he became a follower of the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin and joined the anarchist movement. Atabekian started the "Anarchist Library" in Geneva. This group published important anarchist books in Armenian and Russian. They planned to secretly send these books into the Russian Empire. He also worked with the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) to help publish their newspaper, Droshak.

Atabekian continued his medical studies in Paris. There, he started Hamaink, the first anarchist newspaper in the Armenian language. He wrote a lot about how Armenians were treated unfairly by the Ottoman Empire and European countries. He also shared his ideas for a big social change in Armenia. He stopped publishing after hearing about the Hamidian massacres, which were terrible killings of Armenians. After this, he reconnected with other anarchists in the ARF. They sent a message to a big international meeting, speaking out against the Ottoman Empire's actions and Europe's silence. After becoming a doctor, Atabekian moved to Rasht, Iran. He worked as a doctor there and published a Persian version of Hamaink. During World War I, he worked as a doctor for soldiers and helped refugees who had escaped the Armenian genocide.

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, he moved to Moscow. He started writing about anarchist ideas. He didn't agree with the Bolsheviks, a powerful political group who took control, because he felt they went against what ordinary people wanted. Instead, he supported the idea of people working together in co-operative groups. He saw potential in Moscow's house committees as a way to create a society based on shared ownership and cooperation. He also became Peter Kropotkin's personal doctor and friend, staying with him until Kropotkin's death. After Kropotkin died, Atabekian helped manage a museum dedicated to him.

Atabekian had a stroke and passed away at his home in Moscow in 1933. Some reports later incorrectly said he died in a forced labor camp, known as the Gulag, after anarchists were suppressed when Stalin came to power. Today, Atabekian is seen as an important example of an anarchist thinker from outside Western Europe. His ideas about freedom from authority, cooperative economics, and tenants' rights are still studied.

Contents

Alexander Atabekian's Life Story

Early Years and Joining the Movement

Alexander Movsesi Atabekian was born on February 2, 1869, in Shushi. This city is located in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. He came from a well-known Armenian family, and his father was also a doctor.

After finishing high school in his hometown in 1889, he left the Caucasus region. He traveled to Switzerland to study medicine at the University of Geneva. While he was a student, Atabekian worked as a typesetter for a newspaper called Hunchak. This newspaper was the official voice of the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party (SDHP). It shared news about growing anti-Armenian feelings in the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire.

In 1890, Atabekian left the SDHP. He became an anarchist communist after reading Words of a Rebel by Peter Kropotkin. Anarchist communism is a belief in a society without government, where people share resources. Atabekian then started working at a Ukrainian publishing house. He used it to print anarchist writings translated into Armenian and Russian. He also published open letters from the international anarchist movement to Armenian farmers and revolutionaries.

Soon, Atabekian met many important anarchists. He became close friends with Kropotkin and others. He also met Max Nettlau and Paraskev Stoyanov. Together, they printed a poster remembering the Haymarket martyrs. These were people who were executed after a bombing in Chicago. They put these posters all over Geneva.

Publishing Anarchist Ideas

When a terrible famine hit Russia in 1891, Atabekian decided to secretly send anarchist writings into the Russian Empire. He wanted to print texts in both Russian and Armenian. Atabekian and Stoyanov went to London to visit Kropotkin. They told him they planned to deliver pamphlets to Ukraine and the Caucasus. They had friends there who supported their ideas. Atabekian then went back to Geneva. He set up a printing press in his own bedroom. He called it the Anarchist Library. This was the first Russian anarchist group to print propaganda since the 1870s.

He had planned to start by publishing a Russian version of Words of a Rebel. But Kropotkin was too busy to translate much of it. Atabekian also didn't have enough money to publish a regular newspaper at first. So, he decided to start by publishing single pamphlets. His first publication was a Russian version of Mikhail Bakunin's The Paris Commune and the Idea of the State. In 1892, he published Kropotkin's The Destruction of the State. In 1893, he published more of Kropotkin's works. He also published books by other anarchists like Errico Malatesta. Atabekian wrote a special introduction for the Armenian readers of Malatesta's book.

In 1894, he published more pamphlets. The first pages of these pamphlets had the words "Authorized by the Ministry of Education" printed in Turkish. These pamphlets were widely shared among Armenians living abroad. They also reached Armenia itself. Even with their efforts, Atabekian mostly failed to smuggle the pamphlets into the Russian Empire. But other Russian anarchists in Geneva continued their work a few years later. During this time, he also connected with the new Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF). He helped publish their newspaper Droshak with Stepan Zorian.

After getting his first degree, Atabekian moved to France to continue his medical studies. He first went to Lyon. There, he worked for a few months at a modern clinic. While in Lyon, he saw the assassination of Sadi Carnot by Sante Caserio. He also saw the angry reactions against Italians that followed. This made him turn against the anarchist idea of "motiveless terrorism" (using violence to spread ideas). His publishing work slowed down, but he kept preparing to publish a magazine in Armenian. He then moved to Paris. There, he started publishing Hamaink (meaning "Community"). This was the first anarchist newspaper in the Armenian language. It had five issues, each with eight pages. It contained articles about anarchism and the Armenian national movement.

Atabekian believed Armenia was ready for a revolution. This was because of the harsh rule of the Ottoman Empire. He also saw how Armenian workers were being used in Europe and America. He called for land to be shared by everyone and for Armenia to govern itself. While he strongly opposed Ottoman rule, he also warned against European countries getting involved. Atabekian also published articles from the ARF. But he added his own criticisms of how controlling and centralized Armenian political parties were. The newspaper mainly focused on Armenia. But it also covered anarchist movements in other countries like France, Italy, and Russia. Atabekian did not sign his own articles. This was to protect himself from being arrested for his anarchist activities. Hamaink quickly became popular among Armenians living in Europe.

Moving East and Helping Others

Atabekian stopped all his publishing after hearing about the Hamidian massacres. These were terrible killings of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, and the news deeply saddened him. As Armenians resisted these massacres, he connected with anarchist and libertarian socialist activists within the ARF. These anarchists mixed socialist anarchism with a form of Armenian nationalism.

In 1896, Atabekian became a Doctor of Medicine. He was not allowed to return to the Russian Empire because he had been exiled for his anarchist activities. So, he first moved to Bulgaria. There, he helped Armenians who had escaped the Hamidian massacres. His letters show that he then traveled through Istanbul and İzmir. He tried to spread anarchist ideas among the local Armenian communities. By the early 1900s, he had settled in Rasht, in the Gilan province of Iran. He worked as a doctor there and published an Iranian version of Hamaink, translated into Persian. During this time, he also trained a young man named Ardeshir Ovanessian as a pharmacist. Ovanessian later became a leader of the Iranian Communist Party.

When World War I started, Atabekian was allowed to return to the Russian Empire. There was a big shortage of doctors for soldiers, so the government overlooked his past. Atabekian was quickly put in charge of a field hospital in Baku. But he became very sick with typhoid fever and had to take time off. He got better by early 1915. He was then put in charge of a military hospital in Kars province. His wife, Ekaterina, was also working there. He treated wounded soldiers and civilians, including refugees from the Armenian genocide. He traveled often to different battle areas. He saw the results of battles in places like Karakilisa and Muş. By the end of 1916, his hospital ran out of medicine. His requests for more supplies from Moscow were not answered. This led to most of the medical staff leaving, and the hospital closed. Atabekian left the front lines and returned to Rasht.

Writing During the Russian Revolution

After the February Revolution in 1917, Atabekian moved to Moscow. He became active in politics again. After the October Revolution that followed, he wrote articles for Anarkhiia. He urged anarchists to lead a social revolution. He also criticized the Bolsheviks for taking power. He published an open letter to Kropotkin. In it, he strongly criticized the Imperial Russian Army's attacks on Armenian and Kurdish people. He compared these attacks to the German occupation of Belgium.

During this time, Atabekian started calling himself a "political atheist." He believed that any form of power would always go against what ordinary people wanted. In his book Bloody Week in Moscow, Atabekian described the October Revolution as a "revolution from above." He thought it was done against the will of the people, who mostly didn't care about the revolution. He predicted it would fail because of this. He compared the Bolsheviks' actions to Marxist ideas. These ideas said that a revolution could only happen when conditions were right. He concluded that these conditions were missing in the October Revolution. He felt it was forced from above, not from the people themselves. He then called for anarchists to work towards building a new society through workers' self-management (where workers control their own workplaces).

Atabekian put his hopes in Moscow's "house committees." These committees were set up to protect the common interests of people living in buildings. They also regulated landlords to make sure repairs and heating were provided. Atabekian believed these committees could help meet people's needs. He thought they could build a new social order without political parties. When the Russian Civil War began, Atabekian started supporting the creation of an independent anarchist army. This army would be organized in a decentralized way, without a central authority. It would defend people against the rising White movement. This idea was taken up by Nestor Makhno. He formed groups of fighters in villages across Ukraine.

On April 12, 1918, the Bolsheviks began to crack down on the anarchist movement. They forcibly closed the Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups and shut down Anarkhiia. Soon after, Atabekian and Herman Sandomirskyi started a new printing cooperative. From this, they published their new newspaper, Pochin. Atabekian edited Pochin and did the typesetting himself. It ran for 11 issues. It published letters from Peter Kropotkin and Atabekian's own stories from West Asia. In the newspaper, Atabekian expanded on Kropotkin's ideas of mutual aid and co-operative economics. Mutual aid is when people help each other. Cooperative economics is an economic system where businesses are owned and run by their members.

Atabekian saw cooperation as a "law of life." He believed it came from the way living things and human societies developed. He thought it was key to creating a society based on shared ownership and cooperation. He studied history and concluded that the co-operative movement was different from capitalism and other economic forms like state socialism. This was because it wasn't about making profit. It also aimed to end wage labour (working for a wage). He also believed it upheld a morality based on "freedom, equality, and justice." He also defined the co-operative movement as being against the state. He believed that getting rid of the state would lead to a cooperative society. This society would be based on mutual aid and voluntary labour. He therefore said the co-operative movement was against state socialism. He called state socialism imperialistic and limited by its borders. In contrast, the co-operative movement was internationalist in its methods.

Atabekian tried many times to get Peter Kropotkin to write for Pochin. But Kropotkin always refused. He was busy writing his last book, Ethics: Origin and Development. Atabekian still kept Kropotkin updated on the publication. Kropotkin gave him helpful advice on an article that talked about how animals claim territory versus how states claim land. Atabekian changed the article a lot before publishing it. On October 24, 1920, the Cheka (Soviet secret police) arrested Atabekian. He was accused of speaking out against the Soviet government. During his questioning, he tried to show he was dedicated to the revolution. He said he was not "anti-Soviet" but openly admitted to being "anti-State." He was first sentenced to two years in a labor camp. But this was quickly changed to six months. On January 2, 1921, Atabekian was released early from prison. This happened after Peter Kropotkin asked Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich for his release. Atabekian then tried to get the ban on Pochin lifted. He eventually got permission from Lev Kamenev to start publishing again.

Kropotkin's Final Days

By 1921, Kropotkin had moved to Dmitrov, a small town near Moscow. Atabekian visited him regularly. During this time, Atabekian had gone back to being a doctor. The two friends often wrote letters to each other. After meeting with the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, Kropotkin told Atabekian that he had asked for a friend's release from the Cheka. Kropotkin regretted his visit, but when he asked Atabekian if he disapproved, his friend said he would "approve of pleading even to the Tsar to save those who were condemned to death." Kropotkin also said he had asked Lenin to stop the Red Terror. This was a period of political repression. He feared it would be like the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. He thought this had scared Lenin enough to reduce the executions. Kropotkin also told Atabekian that he worried the Bolsheviks might "bury the revolution."

When Kropotkin became sick with pneumonia, Atabekian traveled to Dmitrov to care for him. Five other doctors joined Atabekian, including Dmitry Pletnyov. Lenin himself had sent these doctors to treat Kropotkin. Even though Kropotkin was very sick, his doctors thought he could still get better. Kropotkin himself said he didn't want to die because he still had work to do. As his condition worsened, Kropotkin began to accept that he was dying. He expressed regret that he had "give[n] trouble to so many good people." He continued to talk with his friends until his last moments. He once said to them, "what a hard business—dying."

Kropotkin died on February 8, 1921. His family and Atabekian were by his side. Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman arrived the next day to pay their respects. The Bolshevik government offered Kropotkin a state funeral. But his family refused. Instead, they formed a committee to arrange his funeral. Atabekian was one of the organizers. Kropotkin's family and friends were allowed to use his old home in Moscow. They turned it into a museum about his life and work. Atabekian served on the museum's committee. He worked with Nikolai Lebedev and Aleksei Solonovich.

Later Life and Passing

On August 29, 1921, the Cheka arrested Atabekian again. The charges were the same as his previous arrest. But Lev Kamenev stepped in, and Atabekian was released the next month. The Soviet authorities briefly allowed Pochin to be published again. But it was banned once more in 1922. Atabekian's printing equipment was taken away, ending his publishing career. In the last issue of Pochin, he published a letter from Kropotkin from late 1918. Without his publishing work, he tried to make a living doing various small jobs. He eventually returned to working as a doctor. Atabekian was also allowed by the authorities to continue his work with the Kropotkin Museum Committee. This was for most of the period of the New Economic Policy (NEP). In 1927, Atabekian and other anarchists organized a protest. It was against the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. They got permission from the Moscow Soviet to do this.

By this time, the Kropotkin Museum Committee was having internal arguments. This started to affect the entire Russian anarchist movement. Atabekian saw the committee as a way to spread anarchist ideas. He disagreed with Kropotkin's widow, Sofia. She wanted to avoid any conflict with the authorities. Atabekian and other anarchists were eventually removed from the committee. But even this did not save the Museum from closing. After Joseph Stalin's rise to power and the start of totalitarianism in the Soviet Union, the anarchist movement was severely repressed. Soon, all the remaining members of the Kropotkin Museum Committee were arrested, sent away, or killed. The museum itself was closed by the Soviet authorities.

In 1930, Atabekian had a stroke. This forced him to retire. He spent his last years in his apartment in Moscow, living with his son. He died on December 5, 1933. However, sources have disagreed on the exact details of his death. Some say he died in a forced labor camp or disappeared into exile. In 1951, the Russian anarchist magazine Delo Truda published memories from I. Zhemchuzhnikov. He was a doctor who worked in the Gulag. He reported that in 1940, he treated an old anarchist named Alexei or Alexander Atabekian. This man died of a heart attack towards the end of that year. This version was later used in other books and encyclopedias. American historian Paul Avrich also reported that Atabekian was among those arrested and imprisoned in the Gulag. He said Atabekian died either in prison or in exile within a few years of 1929.

Atabekian's Lasting Impact

Even though Marxism-Leninism became the main political idea in Armenia, Atabekian's anarchist ideas became popular among Armenians living in other countries. This inspired the creation of Armenian-language anarchist newspapers in the United States. Today, Atabekian is considered one of the most important anarchist thinkers from the former Russian Empire. His ideas about the October Revolution were studied by later anarchists in the 20th and 21st centuries. In an April 1924 newspaper, Atabekian's writings were quoted by Ukrainian Jewish anarchist Anatolii Horelik. He warned against ignoring ethical considerations in revolutionary methods.

In the 21st century, Atabekian is seen as a key example of an early anarchist thinker from outside the Western tradition. His support for house committees has also been taken up by Ukrainian city planners Olena Zaika and Oleh Masiuk. They said his work was important for research on how to organize city spaces.

Atabekian left a large collection of his work. But it was destroyed by a bomb that hit his family's house during the Battle of Moscow. Information about Atabekian is also hard to find in Russian government records. This has made it difficult to create a full picture of his life. Some of Atabekian's papers have been saved and stored by the International Institute of Social History. This institute collected his letters from Peter Kropotkin. This collection is now the world's largest archive of Kropotkin's works.

Selected Writings by Atabekian

- Thesis

- "De la pathogénie de l'angine de poitrine" / "On the Pathogenesis of Angina Pectoris" (1896, edited by Henri Stapelmohr)

- Letters

- "To the Armenian Villagers" (1890)

- "Letter to Armenian Revolutionaries from an International Anarchist Organization" (1890)

- "To the Revolutionary and Libertarian Socialists" (1896)

- "Открытое письмо П. А. Кропоткину" / "Open Letter to P. A. Kropotkin" (1917, Anarkhiia no. 7)

- Pamphlets

- "Кровавая неделя в Москве" / "The Bloody Week in Moscow" (1917)

- "Возможна ли анархическая социальная революция" / "Is Anarchist Social Revolution Possible?" (1918, Pochin)

- "Основы земской финансовой организации без власти и принуждения" / "Fundamentals of Zemstvo Financial Organisation Without Power and Coercion" (1918)

- "Перелом в анархистском учении" / "A Break in Anarchist Doctrine" (1918, Pochin)

- "Социальные задачи домовых комитетов" / "Social Tasks of the House Committees" (1918, Pochin)

- "Дух погромный" / "The Pogrom Spirit" (1919, Pochin)

- "Кооперация и анархизм" / "Cooperation and Anarchism" (1919, Pochin)

- Articles

- Կառավարության կոչումը / "The Call of the Government" (1894, Hamaink no. 1)

- "Յեղափոխական կազմակերպութիւն" / "Revolutionary Organization" (1894, Hamaink no. 3)

- "Проблема свободной армии" / "The Problem of a Free Army" (1918, Anarkhiia no. 83)

- "Контр-революция разгуливает" / "Counter-Revolution Goes Wild" (1918, Anarkhiia no. 90)

- "Коммунизм и Кооперация" / "Communism and Cooperation" (1920, Pochin no. 3)

- "Территориальность и анархизм" / "Territoriality and Anarchism" (1920, Pochin no. 11)

- "Из воспоминаний о П.А. Кропоткине" / "In Memory of P.A. Kropotkin" (1922, Pochin no. 6–7)

- Collections

- Против власти: сборник статей / Against Power: a collection of articles (2013, Librocom; ISBN: 9785397031660; )

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |