National Popular Vote Interstate Compact facts for kids

| Date written | February 2006 |

|---|---|

| Date active | Not active |

| Condition | Becomes active when members control most of the Electoral College (at least 270 electoral votes). Only active for those members. |

| Members | Maryland New Jersey |

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) is an agreement between some U.S. states and the District of Columbia. It aims to change how the Electoral College chooses the president of the United States.

States in this agreement promise to give all their Electoral College votes to the person who gets the most votes from regular people across the entire country. This is called the "national popular vote." The agreement will only start working when enough states join to guarantee that the national popular vote winner becomes president.

Right now, eleven states and the District of Columbia are part of the agreement. Together, they have 172 "electoral votes." The agreement will become active when states with a total of 270 electoral votes join. This is the number needed to win the presidency.

Contents

How the Agreement Works

The NPVIC is an agreement between states. It will become active when the states that are part of it control most of the Electoral College. Until then, these states will give their electoral votes as they do now.

Once the agreement is active, member states will give all their electoral votes to the person who wins the most votes from people in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. This person wins the "popular vote" across the country. This way, the person with the most individual votes will become president.

The U.S. Constitution lets each state decide how to give out its Electoral College votes. This is written in Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2. The Constitution does not say exactly how states must do this. For example, most states today give all their electoral votes to the person who wins the most votes in that specific state. However, Maine and Nebraska split their electoral votes based on different areas within their states. The NPVIC changes how its member states give out their electoral votes.

Why This Agreement Exists

Sometimes, a person has become president even if another person got more votes from people across the country. Many Americans want the person with the most votes to win. In 2007, a survey showed that 72% of Americans wanted to change the Electoral College to a direct vote. This included people from different political groups. Surveys since 1944 have often shown that most Americans want a direct vote, except in 2016.

Here are some reasons why people support the NPVIC:

- The popular vote winner doesn't always win: This has happened five times in U.S. history (1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016). For example, in 2000, Al Gore got more votes than George W. Bush across the country. But Bush won more electoral votes and became president. In 2016, Hillary Clinton got nearly 3 million more votes than Donald Trump. However, Trump won more electoral votes by winning key states like Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

- Focus on "swing states": Today, people running for president often spend most of their time and money in a few "swing states." These are states where the election is usually very close. A small change in votes there can greatly affect the Electoral College. This means problems in swing states get a lot of attention, while other states are often ignored. In the 2004 election, candidates spent three-quarters of their money in only five states. They didn't even visit 18 states.

- Lower voter turnout in some states: When people think they know who will win their state, they might feel their vote doesn't matter. This can lead to fewer people voting in states where the election isn't close. For example, in 2004, more young people voted in the ten closest states than in other states.

Debate About the Agreement

Many newspapers support the NPVIC, like The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. They say the current system makes people not want to vote and focuses too much on a few states. Other newspapers, like The Wall Street Journal, are against it. Some people worry the agreement might give too much power to big cities or states with many people.

Here are some of the main arguments:

Attention to States

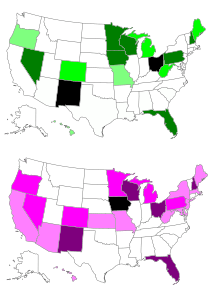

Today, presidential candidates spend most of their money and time in states where the vote is expected to be close. Other states are often ignored. The maps show how much advertising and how many visits the top two candidates made in 2004. This is adjusted for the number of people in each state.

Supporters of the NPVIC say it would make candidates try to get votes in every state. People against the NPVIC worry that states with fewer people and fewer cities might not get enough attention.

Fairness and Close Elections

Some people are against the NPVIC because they worry about cheating. They argue it might be easier to add a few fake votes in many places than a lot of fake votes in just a few places. However, supporters say that adding up all the votes in the country would make cheating harder to do. Today, the winner can be decided by a very small number of votes in just one state.

The NPVIC does not say how to count votes again if the national result is very close. Each state handles its own vote counting. Supporters of the agreement say that a very close result is less likely when counting votes from the whole country than from just one state.

Power of States

People disagree about whether the Electoral College helps states with few people or states with many people. The Electoral College is not designed to give power based exactly on population. States with fewer people have more electoral votes per person than states with many people. However, some argue that states with many people have more power because they control so many electoral votes at once. The NPVIC aims to give the same power to every person's vote, no matter where they live.

Helping One Political Party

Some people think the NPVIC would help one political party more than another. For example, some Republicans worry it would help Democrats and people in cities. However, other Republicans believe it could help their party. Experts say the agreement doesn't really help one party over the other in the long run. In recent elections, sometimes Democrats had an advantage, and sometimes Republicans did.

State vs. National Votes

The NPVIC could make a state give its electoral votes to someone who did not win the most votes in that specific state. Because of this, two governors (from California and Hawaii) at first stopped their states from joining the agreement. (Both states later joined.) Supporters of the agreement say that the number of votes in any one state is not as important as the choice of most people in the whole country.

Is it Legal?

Supporters of the NPVIC say it is legal and allowed by the U.S. Constitution. Article II of the Constitution lets states decide how to give out their electoral votes. Legal experts who helped create the agreement believe it fits within the Constitution.

Some people have worried that the agreement might go against the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which protects minority voters. However, the U.S. Department of Justice decided that the agreement does not harm minority voters. It allowed California to join in 2012.

There's also a question about whether the agreement needs approval from the U.S. Congress. The Constitution says that agreements between states need Congress to approve them. But the U.S. Supreme Court has said this is not always true. They said only agreements that threaten the power of the U.S. government need approval. Supporters of the NPVIC argue it doesn't threaten the government's power because states already have the right to decide how to give their electoral votes. Others disagree, saying it does affect the U.S. government system. Even though supporters don't think it needs approval, they plan to ask for it anyway.

History of the Idea

Past Plans to Change the Constitution

In the past, people tried to end the Electoral College by changing the Constitution. This is called an "amendment." It's very difficult to do. First, two-thirds of the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives must agree. Then, three-quarters of all the states must approve the change.

One plan, called the Bayh-Celler plan, came close to success in 1969. It would have replaced the Electoral College with a popular vote system. The plan passed in the House of Representatives but was stopped in the Senate. Other similar plans were introduced later but did not pass.

A New Plan Using State Agreements

In 2001, a law professor named Robert Bennett came up with a new idea. His plan didn't need a change to the Constitution. Instead, it used the power states already have. He suggested that a group of states that control most of the Electoral College could work together. They would make the popular vote decide who wins presidential elections.

Two other law professors, brothers Akhil Reed Amar and Vikram Amar, supported this idea. They suggested an agreement between states, made into laws in each state. The states would agree to give all their electoral votes to the person who won the national popular vote. This agreement would only become active when it guaranteed that the popular vote winner would also win the Electoral College. This idea became the NPVIC.

The Amar brothers' plan uses two parts of the Constitution:

- Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2: This part lets each state decide how to give out its electoral votes.

- Article I, Section 10, Clause 3: This part, called the "Compact Clause," lets states make agreements with each other.

Organization and How it Started

In 2006, a computer science professor named John Koza wrote a book called Every Vote Equal. The book argued for the National Popular Vote agreement. Koza and others then created a non-profit group called National Popular Vote. This group works to promote the NPVIC. It includes leaders from both major political parties.

In 2006, several states began looking at bills to join the NPVIC. The Colorado Senate approved a bill that year. Both parts of the California legislature approved a bill, but Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger stopped it.

States Joining the Agreement

In 2007, 42 states considered bills to join the NPVIC. Maryland was the first state to join the agreement when its Governor, Martin O'Malley, signed it into law on April 10, 2007.

So far, eleven states and the District of Columbia have joined the agreement. In Colorado, both parts of the legislature have approved the bill, and it is waiting for the Governor to sign it.

All 50 states have looked at bills to join the NPVIC. Some states have had one part of their legislature approve it, but not both. Some states, like Maryland, New Jersey, and Washington, have had bills to leave the agreement, but these bills failed.

| Number | Place | Date joined | Way of joining | Current Electoral votes (EV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maryland | April 10, 2007 | Signed by Gov. Martin O'Malley | 10 |

| 2 | New Jersey | January 13, 2008 | Signed by Gov. Jon Corzine | 14 |

| 3 | Illinois | April 7, 2008 | Signed by Gov. Rod Blagojevich | 20 |

| 4 | Hawaii | May 1, 2008 | Legislature overturned veto by Gov. Linda Lingle | 4 |

| 5 | Washington | April 28, 2009 | Signed by Gov. Christine Gregoire | 12 |

| 6 | Massachusetts | August 4, 2010 | Signed by Gov. Deval Patrick | 11 |

| 7 | District of Columbia | December 7, 2010 | Signed by Mayor Adrian Fenty (see note) | 3 |

| 8 | Vermont | April 22, 2011 | Signed by Gov. Peter Shumlin | 3 |

| 9 | California | August 8, 2011 | Signed by Gov. Jerry Brown | 55 |

| 10 | Rhode Island | July 12, 2013 | Signed by Gov. Lincoln Chafee | 4 |

| 11 | New York | April 15, 2014 | Signed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo | 29 |

| 12 | Connecticut | May 24, 2018 | Signed by Gov. Dannel Malloy | 7 |

| Total | 172 | |||

| Percentage of 270 | 63.7% | |||

The U.S. Congress can stop laws in the District of Columbia, but they did not stop this one.

Public Votes on Laws

Some states allow citizens to vote directly on laws, which is called an "initiative" or "referendum." First, people supporting the law must get a certain number of signatures. Then, the question can be put to the voters. In 2018, groups in Arizona, Maine, and Missouri tried to get initiatives to join the agreement, but they didn't get enough signatures.

Future Chances

An election expert named Nate Silver believes the NPVIC needs support from "red" states (states that usually vote Republican) to succeed. So far, mostly "blue" states (states that usually vote Democrat) have joined. However, some Republican-controlled legislatures have agreed to join the agreement in states like Arizona, Oklahoma, and New York.

Images for kids

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |