New South Greenland facts for kids

New South Greenland, also called Morrell's Land, was a piece of land that an American captain named Benjamin Morrell claimed to have seen. He reported seeing it in March 1823. This happened while he was on a seal hunting and exploration trip. His ship, the schooner Wasp, was in the Weddell Sea area of Antarctica.

Morrell gave exact locations and described a coastline. He said he sailed along this coast for more than 300 miles (480 km). The Weddell Sea is in Antarctica. It was very hard to travel through because of many icebergs. So, few people explored it back then.

No one properly checked Morrell's sighting at the time. Later trips to Antarctica in the early 1900s proved that there was no land where Morrell said it was. When Morrell made his voyage, the Weddell Sea was mostly unknown. This made his sighting seem possible at first.

However, Morrell made clear mistakes when he told his story. He also had a reputation for making up stories. These two things made many people doubt his claim. In June 1912, the German explorer Wilhelm Filchner's ship Deutschland got stuck in ice in the Weddell Sea. It drifted into the area where Morrell reported the land.

Filchner searched for the land but found no trace of it. He measured the sea bottom and found over 5,000 feet (1,500 m) of water. This showed there was no land nearby. Three years later, Ernest Shackleton's ship Endurance also got stuck in the same waters. He used similar methods to confirm that the land did not exist.

People have suggested different reasons for Morrell's mistake. One idea is that Morrell wanted to trick others with his claim. However, Morrell describes his sighting briefly. He does not try to get personal credit or glory for the discovery. In his story, he gives all credit to his fellow sealing captain, Robert Johnson. Johnson supposedly found and named the land two years earlier.

Morrell might have been honestly mistaken. He could have miscalculated his ship's position. Or he might have misremembered details when writing his account nine years later. Another idea is that he confused distant icebergs with land. This was a common mistake. He might also have been fooled by the strange effects of an Antarctic mirage. In 1843, the famous British naval explorer James Clark Ross also reported possible land close to Morrell's spot. This land also turned out not to exist.

Contents

The Wasp Voyage: 1822–23

First Part: June 1822 to March 1823

In the early 1800s, people knew almost nothing about the geography of Antarctica. But some sightings of land had been reported. Benjamin Morrell was made commander of the schooner Wasp. This was for a two-year trip to hunt seals, trade, and explore. The trip was in the Antarctic seas and the southern Pacific Ocean in 1822.

Besides his sealing duties, Morrell had "discretionary powers to prosecute new discoveries." This meant he could explore new areas. He planned to use this power to explore the Antarctic seas. He also wanted to see if it was possible to reach the South Pole. This was the first of four long voyages for Morrell. He spent most of the next eight years at sea. However, he did not go back to the Antarctic after this first trip.

The Wasp left New York on 22 June 1822. It reached the Falkland Islands in late October. Morrell then spent 16 days looking for the nonexistent Aurora Islands. After that, he headed for South Georgia, where the ship anchored on 20 November. In his story, Morrell wrongly wrote down the position of this anchorage. He placed it about 60 miles (97 km) southwest of the island's coastline, in open sea.

The Wasp then went east to hunt for seals. Morrell claimed the ship reached the remote Bouvet Island on 6 December. He said he found this hard-to-find island easily. Historian H.R. Mill noted that Morrell's description of the island did not mention its most unique feature. The island is covered by a permanent ice sheet.

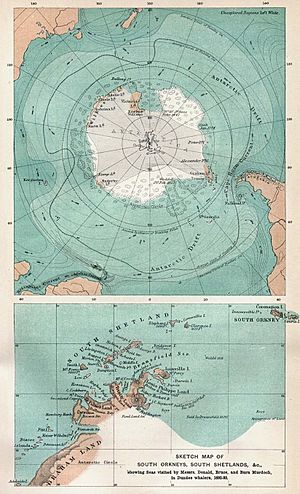

Morrell then tried to take the ship south. He reached thick ice around 60°S. He decided to turn northeast towards the Kerguelen Islands. He anchored there on 31 December. After exploring and sealing for several days, the Wasp left the Kerguelens on 11 January 1823. It sailed south and east. It reached its furthest eastern point at 64°52'S, 118°27'E on 1 February.

From this point, Morrell said he used strong easterly winds. He made a fast trip westward back to the Greenwich meridian, 0°. His story does not have many details. But it says he covered more than 3,500 miles (5,600 km) in 23 days. Many people have doubted if such fast, direct travel was possible in ice-filled waters. Especially since Morrell mentioned southern latitudes during the trip. These later turned out to be at least 100 miles inside the then-undiscovered Antarctic continent.

On 28 February, the Wasp reached Candlemas Island in the South Sandwich Islands. After a few days looking for fuel for the ship's stoves, the Wasp sailed south on 6 March. It went into the area later known as the Weddell Sea. Morrell found the sea surprisingly free of ice. He went to 70°14'S before turning northwest on 14 March.

Morrell said he turned back because the ship was low on fuel. Otherwise, he claimed, he could have taken the ship to 85°, or even to the Pole itself. These words are very similar to what the British explorer James Weddell wrote. Weddell described his own experiences in the same area, a month earlier. This has made historians think that Morrell might have copied parts from Weddell's account.

Sighting of Land

At 2 pm the next day, 15 March, the Wasp was sailing northeast. Morrell wrote: "land was seen from the masthead, bearing west, distance 3 leagues" (about nine miles, 14 km). His story continues: "At half past 4 pm we were close on with the body of land to which Captain Johnson had given the name of New South Greenland."

Robert Johnson was a former captain of the Wasp. He had explored the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula in 1821. Johnson had called it "New South Greenland." Morrell casually mentioned Johnson's description. This suggests Morrell thought the land he was seeing was the east coast of the peninsula. At the time he wrote this, his position was about 14 degrees east of that peninsula. People did not know the geography of the peninsula when Morrell made his voyage.

Morrell described seal hunting activities continuing along this coast for the rest of the day. The next morning, sealing continued as the ship moved slowly south. It stopped when Morrell called a halt "because of shortage of water and season far advanced." He saw mountains of snow about 75 miles (120 km) further south.

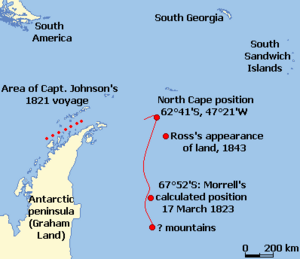

Morrell turned north from a position he calculated as 67°52'S, 48°11W. Three days later, on 19 March, the ship passed what he thought was the northern cape of the land. This was at 62°41'S, 47°21'W. "This land abounds with oceanic birds of every description," Morrell wrote. He also said he saw 3,000 sea elephants. At 10 o'clock, the Wasp "bade farewell to the cheerless shores of New South Greenland." There is no more mention of it in his long voyage story. The Wasp sailed for Tierra del Fuego, then through the Strait of Magellan into the Pacific Ocean. It reached Valparaiso, Chile, on 26 July 1823.

Since the first trips to the Southern Ocean in the 1500s, explorers have reported lands that later turned out not to exist. Polar historian Robert Headland has suggested various reasons for these false sightings. These range from "too much rum" to deliberate hoaxes. Hoaxes were meant to trick rival ships away from good sealing areas. Some sightings might have been of large ice masses carrying rocks. Dirty ice can look very much like land. It is also possible that some of these lands existed but later sank after volcanic eruptions. Other sightings might have been of real land, but explorers wrongly located them. This could be due to broken clocks, bad weather, or simple mistakes.

Searching for Morrell's Land

People started to doubt New South Greenland when, in 1838, the French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville sailed over the spot of Morrell's "north cape." He saw no sign of land. This evidence, along with mistakes in Morrell's story, made many geographers ignore his claims. This doubt remained even after Sir James Clark Ross reported seeing land in 1843. This was not far from Morrell's supposed sighting. Ross's sighting was sometimes used to support Morrell's claim.

No one explored the Weddell Sea further until 1903. Then, William Speirs Bruce took Scotia to 74°1'S. However, he was not close to Morrell's or Ross's sightings. Bruce generally thought well of Morrell. He wrote that Morrell's claims should not be rejected until they were absolutely proven wrong.

The first serious search for New South Greenland happened during the Second German Antarctic Expedition, 1911–13. This was led by Wilhelm Filchner. The expedition's ship, Deutschland, got stuck in heavy sea ice. It was trying to set up a base at Vahsel Bay. By mid-June 1912, its drift had brought it 37 miles (60 km) east of Morrell's recorded sighting.

Filchner left the ship on 23 June. With two friends and enough supplies for three weeks, he sledged westward across the sea ice. He was looking for Morrell's land. There were only two or three hours of daylight each day. Temperatures dropped to −31 °F (−35 °C). This made travel difficult. In these conditions, the group covered 31 miles (50 km). They took frequent measurements. They found no signs of land. A heavy weight dropped through the ice reached a depth of 5,248 feet (1,600 m) before the line broke. This depth confirmed there was no land nearby. Filchner concluded that what Morrell had seen was a mirage.

On 17 August 1915, Sir Ernest Shackleton's ship Endurance was also stuck in the ice. It drifted to a point 10 miles west of Morrell's charted position. Here, a depth measurement showed 1,676 fathoms (10,060 feet, 3,065 m) of water. Shackleton wrote: "I decided that Morrell Land must be added to the long list of Antarctic islands and continental coasts that have resolved themselves into icebergs." On 25 August, another measurement of 1,900 fathoms (11,400 feet, 3,500 m) gave Shackleton more proof that New South Greenland did not exist.

Filchner's and Shackleton's findings proved that New South Greenland was a myth. However, there was still the question of Sir James Ross's reported land. Ross's reputation was strong enough for his sighting to be taken seriously. It was even recorded on maps. In 1922, Frank Wild led the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition aboard Quest. He investigated the location of Ross's sighting. They saw nothing. Ice conditions stopped them from reaching the exact spot. Wild took a measurement at 64°11'S, 46°4'W. It showed 2,331 fathoms (13,986 ft; 4,263 m) of water. This proved no land was near.

Ideas and Theories

According to W.J. Mills, Morrell was known among his peers as "the biggest liar in the Southern Ocean." Mills called the westward journey from Morrell's claimed furthest eastern position "impossible." He said it was "unbelievably fast." Mills suggested that Morrell wrote his story nine years after the voyage. He might not have had access to the ship's log. So, he "may have felt constrained to invent details that appeared plausible." This could explain the many errors in positions and dates.

Hugh Robert Mill wrote in 1905, before New South Greenland was proven nonexistent. He mentioned how absurd some parts of Morrell's story were. He concluded that because of Morrell's mistakes and his habit of using others' experiences, all his claims should be treated as unproven. Still, he admitted that "a man may be ignorant, boastful and obscure, and yet have done a solid piece of work."

Canadian geographer Paul Simpson-Housley was more understanding. While he doubted much of Morrell's story, he suggested that the speeds claimed for the western journey were not impossible. He believed that the claimed furthest south in the Weddell Sea was entirely possible. This was because James Weddell had sailed four degrees further south just a month earlier.

Another person who defended Morrell was the writer Rupert Gould. He included a long essay on New South Greenland in his book Enigmas, published in 1929. Gould did not believe that the New South Greenland sighting was simply made up by Morrell. He pointed out that the discovery was given very little importance in Morrell's 500-page book. Gould wrote: "If Morrell wished to gain an undeserved reputation as an Antarctic explorer, one would think he could have gone a better way about it than to bury his pièces justificatives, after he had forged them, in an undistinguished corner of so bulky a book." In the few pages about the Antarctic, Morrell's account of his discovery is short and factual. He gives credit to Captain Johnson, not himself.

Gould also discussed if what Morrell saw was actually the eastern coast of Graham Land. This is also called the "Foyn Coast." It is 14° further west from where New South Greenland was sighted. Gould said that the peninsula's eastern coast matched Morrell's description very well. This theory suggests that Morrell miscalculated the ship's position. Perhaps he did not have the right instruments for navigation. Morrell wrote that he was "destitute of the various nautical and mathematical instruments." But other parts of his story show that he usually calculated his position correctly. A 14° error in longitude is very large. The extra distance of about 350 miles (560 km) to the Foyn coast seems too far. It would be hard to cover that in the ten-day trip from the South Sandwich Islands. Even so, Gould believed that the "balance of evidence" showed that Morrell saw the Foyn coast.

Filchner thought that the sighting of New South Greenland could be explained by a mirage. Simpson-Housley agreed with this idea. He suggested that Morrell and his crew saw a superior mirage. One type of superior mirage is called a Fata Morgana. It makes distant flat coastlines or ice edges look taller and wider. They can appear to have tall cliffs and other features like high mountains and valleys. In his expedition story South, Shackleton described a Fata Morgana he saw on 20 August 1915. This was when his ship Endurance was near the recorded position of New South Greenland. He wrote: "The distant pack is thrown up into towering barrier-like cliffs, which are reflected in blue lakes and lanes of water at their base. Great white and golden cities of Oriental appearance at close intervals along these cliff-tops indicate distant bergs... The lines rise and fall, tremble, dissipate, and reappear in an endless transformation scene."

After the Voyages

Morrell's four voyages finally ended on 21 August 1831. He returned to New York. He then wrote his Narrative of Four Voyages, which was published the next year. He tried to continue his sailing career. He looked for work with the Enderby Brothers shipping company in London. But his reputation had reached them, and he was rejected. Charles Enderby publicly stated that "he had heard so much of him that he did not think fit to enter into any engagement with him."

Morrell also tried to join Jules Dumont d'Urville's expedition to the Weddell Sea in 1837. But his help was again turned down. He reportedly died in 1839. He is remembered by Morrell Island, 59°27'S, 27°19'W. This is another name for Thule Island in the Southern Thule group of the South Sandwich Islands. Robert Johnson, who first named New South Greenland, disappeared with his ship in 1826. He was exploring the Antarctic waters near what would later be known as the Ross Sea.

See also

In Spanish: Nueva Groenlandia del Sur para niños

In Spanish: Nueva Groenlandia del Sur para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |