Benjamin Morrell facts for kids

Benjamin Morrell (born July 5, 1795 – died 1838 or 1839?) was an American sea captain, explorer, and trader. He made many trips, mostly to the Atlantic, the Southern Ocean, and the Pacific Islands. In a book called A Narrative of Four Voyages, which was written for him, Morrell described his life at sea between 1823 and 1832. He claimed to have discovered many places and achieved great things. However, many of these claims have been questioned by experts and some have even been proven wrong.

Morrell had an exciting early life. He ran away to sea when he was 17. During the War of 1812, he was captured and held prisoner twice by the British. Later, he worked as a regular sailor for several years. He then became a chief mate and later a captain of a ship called Wasp, which hunted seals. In 1823, he took Wasp on a long trip to the cold waters near Antarctica. When he returned, he said he had sailed beyond 70 degrees South and seen new coastlines in what is now called the Weddell Sea. These claims were not fully proven. His later trips were mainly in the Pacific Ocean, where he tried to trade with the local people. Even though Morrell wrote about how much money could be made from Pacific trade, his efforts usually did not make much profit.

Even though many people at the time thought Morrell often made things up, some later experts have defended him. They believe that even with all the big talk in his book, he did some useful work. For example, he found large amounts of guano (bird droppings used as fertilizer), which led to a big industry. He is thought to have died in 1838 or 1839 in Mozambique. However, some evidence suggests he might have faked his death and lived in hiding, possibly in South America.

Contents

Early Life and First Sea Adventures

Benjamin Morrell was born in Rye, New York, on July 5, 1795. He grew up in Stonington, Connecticut, where his father, also named Benjamin, built ships. Morrell had little schooling and ran away to sea at age 17 without telling anyone. During the War of 1812, he was captured twice by the British. On his first trip, his ship was stopped near St John's, Newfoundland, and Morrell was held for eight months. His second trip led him to Dartmoor prison in England for two years.

After he was released, Morrell continued to be a sailor. He worked as an ordinary seaman because he didn't have enough education to become an officer. But a kind captain, Josiah Macy, taught him what he needed to know. In 1821, Morrell became the chief mate on a sealing ship called Wasp, working for Captain Robert Johnson.

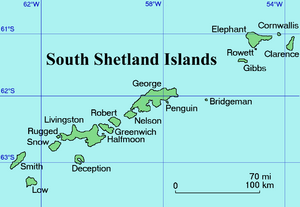

The Wasp was heading to the South Shetland Islands, which had been found three years earlier by Captain William Smith. Morrell had heard stories about these islands and was eager to go there. On this trip, he had many "remarkable adventures." He almost drowned, got lost at sea in a small boat during a storm, and helped free Wasp when it got stuck in the ice. The day after returning to New York, Morrell was made captain of Wasp. Captain Johnson took command of another ship, the schooner Henry. Both ships were sent back to the South Seas to hunt seals, trade, explore, and "find out if it was possible to reach the South Pole."

Morrell's Four Main Voyages

First Voyage: South Seas and Pacific Ocean

The ships Wasp and Henry left New York on June 21, 1822. They stayed together until they reached the Falkland Islands. Then they split up, with Wasp sailing east to find places to hunt seals. Morrell's story of the next few months in the Antarctic and subantarctic waters is quite debated. His claims about distances, locations, and discoveries have been questioned as being wrong or even impossible. This led to many people at the time, and later writers, criticizing him for not always telling the truth.

Exploring Antarctic Waters

Morrell's logbook says that Wasp reached South Georgia on November 20. Then it sailed east towards the lonely Bouvet Island. This island is known as the most remote island in the world. It was first found in 1739 by a French sailor, Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier, but he recorded its position incorrectly. Captain James Cook couldn't find it in 1772 and thought it didn't exist. It wasn't seen again until 1808.

Morrell claimed he found the island easily and landed there to hunt seals. However, in his long description, Morrell doesn't mention the island's most obvious feature: its permanent ice cover. This makes some experts doubt if he actually visited the island.

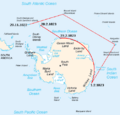

After leaving Bouvet Island, Wasp continued east, reaching the Kerguelen Islands on December 31, 1822. They stayed there for 11 days. The journey then went south and east until February 1, 1823. Morrell wrote his position as 65°52'S, 118°27'E. He said he then turned the ship west. Morrell's logbook is mostly empty until February 23, when he recorded crossing the Greenwich (0°) line. Historians have wondered if such a long journey from 118°E (about 3,500 nautical miles (4,000 mi; 6,500 km)) could have been made so quickly in icy waters and against the winds.

Morrell also claimed Wasp reached the South Sandwich Islands on February 28. His descriptions of the harbor on Thule Island match later expeditions. In the next part of the trip, Morrell said he took Wasp south. He claimed the sea was very clear of ice, and he reached a latitude of 70°14'S before turning north on March 14 because they were running out of fuel. If this story is true, it would make him the first American sea captain to cross the Antarctic Circle. He believed he could have gone "directly to the South Pole, or to 85° without the least doubt" if he had more fuel. Some support for his claim comes from James Weddell's trip a month earlier, who reached 74°15'S. However, Morrell's account was written nine years later, and some of his words are very similar to Weddell's published book. This suggests Morrell might have copied parts of Weddell's experiences.

The Mystery of New South Greenland

Morrell's book says that the day after turning north from his southernmost point, he saw a large area of land around 67°52'N, 44°11'W. Morrell called this land "New South Greenland". He wrote that over the next few days, Wasp explored more than 300 nautical miles (350 mi; 560 km) of its coast. Morrell gave detailed descriptions of the land and its many animals. However, no such land exists there. Other sightings of land in this area, reported by Sir James Clark Ross in 1842, also turned out to be imaginary.

In 1917, explorer William Speirs Bruce said that the idea of land in this area "should not be rejected until absolutely disproved." But by then, both Wilhelm Filchner and Ernest Shackleton, whose ships drifted near where New South Greenland was supposedly located, reported no sign of it. It's possible that what Morrell saw was actually the eastern coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, which is about 400 nautical miles (460 mi; 740 km) further west. This would mean a big navigation mistake. Another idea is that he saw a mirage, which is when light bends to make distant objects appear closer or in different places.

Pacific Adventures and Return Home

On March 19, Morrell "said goodbye to the cold shores of New South Greenland" and sailed away from Antarctica, never to return. The rest of this voyage is not debated. It involved a year-long trip in the Pacific Ocean. Wasp visited the Galápagos Islands and also the island of Más a Tierra. A century earlier, a Scottish sailor named Alexander Selkirk was stranded there, which inspired the famous Robinson Crusoe story. Wasp returned to New York in May 1824. When Morrell arrived, he found that his wife, whom he married in 1819, and his two young children had all died. He quickly married his 15-year-old cousin, Abigail Jane Wood, whom he called "Abby."

Second Voyage: North and South Pacific

For his second voyage, Morrell became captain of a new ship called Tartar. It sailed from New York on July 19, 1824, heading for the Pacific Ocean. Over the next two years, Tartar first explored the American coastline from the Straits of Magellan to Cape Blanco (in what is now Oregon). Then he sailed west to the islands of Hawaii, which were known then as the Sandwich Islands. This was where Captain James Cook had died almost 40 years before. Morrell claimed to have discovered two new islands, Byers's Island and Morell's Island. After that, Tartar returned to the American coast and slowly sailed south back to the Straits of Magellan.

Morrell's logbook describes many events he saw. These included the siege of Callao, the main port of Peru, by Simón Bolívar's forces. He also saw a spectacular volcanic eruption on Fernandina Island in the Galápagos islands in February 1825. Fernandina, then called Narborough Island, erupted on February 14. Morrell wrote that "The heavens appeared to be one blaze of fire, intermingling with millions of falling stars and meteors." He said the flames shot up from the volcano's peak at least two thousand feet high. Morrell reported that the air temperature reached 123°F (51°C). As Tartar got closer to the lava flowing into the sea, the water temperature rose to 150°F (66°C). Some of the crew became sick from the heat.

Morrell also wrote about a hunting trip ashore in California. It led to a fight with the local people that became a full battle. He claimed seventeen natives died and seven of Tartar's men were wounded, including himself with an arrow in his leg. About a visit to San Francisco, Morrell wrote that the people there were "very lazy and consequently very dirty." After visiting the Galapagos Islands again and collecting fur seals and terrapins, Tartar began a slow journey home on October 13, 1825. As they left the Pacific, Morrell claimed he had personally checked and identified every danger along the American Pacific coast. Tartar finally reached New York Harbor on May 8, 1826. They brought back 6,000 fur seals. Morrell's employers were not happy with this amount, as they had expected more. He wrote, "The Tartar did not return home laden with silver and gold, and therefore my hard work and dangers counted for nothing."

Third Voyage: West African Coast

In 1828, Morrell was hired by a company called Christian Bergh & Co. to command a schooner named Antarctic. He claimed it was named to honor his earlier achievements in Antarctica. Antarctic left New York on June 25, 1828, heading for Western Africa. Over the next few months, Morrell explored a large part of the African coast between the Cape of Good Hope and Benguela. He also made several short trips inland. He was very impressed by the trading possibilities of this coast. He wrote that "many kinds of skins may be found here, including those of the leopard, fox, bullock, along with ostrich feathers and valuable minerals." At Ichaboe Island, he found huge deposits of guano, which were 25 feet thick. He believed that a $30,000 investment could make a profit of "from ten to fifteen hundred percent" in two years.

During the voyage, Morrell saw the slave trade several times. First, at the Cape Verde Islands, which was a center for the trade. He found the slaves' living conditions terrible. He wrote a long passage in his journal about the wrongs of slavery. On June 8, 1829, Morrell wrote in his journal: "The voyage had been successful beyond our expectations, and any further stay on the African coast would have been a waste of time and money." He arrived back in New York on July 14.

Fourth Voyage: South Seas and Pacific Ocean

According to Morrell, the owners of Antarctic all agreed that he should make another voyage with the ship. In September 1829, Antarctic left New York, heading for the South Atlantic and Pacific to find seals. His wife, Abby Jane Morrell, insisted on coming along, even though Morrell and the owners advised against it. By January 1830, Antarctic reached the Auckland Islands, south of New Zealand. Morrell had hoped to find many seals there, but the waters were empty. He sailed north to Manila in the Philippines, hoping to find goods to trade. He arrived in March 1830. There were no such goods available, but the American consul, George Hubbell, convinced Morrell that collecting sea cucumbers (also called "Bêche-du-mer") could be profitable. These were common in the islands now known as Micronesia and were highly valued in China.

Hubbell would not let Antarctic sail with Abby on board. Morrell sailed from Manila without her. At first, he had little luck finding many sea cucumbers. Eventually, Antarctic reached the Carteret Islands, a small group of islands that are now part of Papua New Guinea. There, he found many sea cucumbers. Morrell set up a camp on one of the islands. The local people were not friendly, but they were very curious about metal, which they had never seen before. Tools were stolen. Morrell responded by holding several chiefs hostage. In return, the islanders launched a full attack on Morrell's camp on shore. Fourteen crew members were killed. Antarctic had to leave quickly, leaving much equipment behind.

Morrell went back to Manila, planning to get revenge. He hired many Manilans to join his crew. With a loan from the British consul, he prepared Antarctica and added guns and cannons. The ship, with Abby now on board, returned to the Carteret Islands and attacked with gunfire. After several attacks and many casualties, the local people asked for peace. This allowed Morrell to take over one of the islands in exchange for cutlery, jewelry, tools, and other metal items. The peace did not last long. Morrell's shore camp was constantly bothered by the local people. Finally, Morrell decided to give up the project, saying the native people were "unforgiving and always fighting."

On November 13, 1830, while returning to Manila, Antarctica anchored off the coast of Uneapa island (in today's West New Britain Province). Many native canoes approached the ship, full of seemingly well-armed and aggressive islanders. After his experiences at Carteret Island, Morrell took no chances and ordered his crew to fire. The small boats were destroyed; many people died, while others managed to get back to shore. One man, who had held onto Antarctic's rudder, was pulled on board as a prisoner. The crew named him "Sunday"—his real name was Dako. Just over a week later, on November 22, a small fight in the Ninigo Islands brought Morrell another captive, whom the crew named "Monday." With two native prisoners, but little else to show from this trip, Antarctic returned to Manila in mid-December.

Morrell was desperate for a profitable activity. He made some money by showing Dako and Monday to a curious public. The only shipping job available was to take cargo to Cádiz, which he had to accept. He left Manila on January 13, 1831, taking his captives with him. When Antarctic reached Cádiz five months later, the port was closed due to quarantine. He had to unload the cargo in Bordeaux, where Dako and Monday again attracted great interest. Antarctic finally reached New York on August 27, 1831. Even though he hadn't made much money, Morrell was still positive about future opportunities in the Pacific. He wrote that he could "open a new way of trade more profitable than any that our country has ever yet enjoyed." In the last part of his book, Morrell wrote that his wife's father, her aunt, and her aunt's child had all died while he was away, as had one of Morrell's cousins and her husband.

Later Career and Final Years

Making Money

When Morrell returned to New York after his fourth trip, he was in great debt and needed money quickly. Newspapers were very interested in his voyage, and Morrell wanted to make money from it. Within a few days, he organized a stage show called "Two Cannibals of the Islands of the South Pacific." This show, which included exciting stories about the fight at Carteret Island, attracted large crowds at New York's Rubens Peale museum. In October 1831, Morrell took the show on a tour, starting in Albany. Among those who saw the show was 12-year-old Herman Melville, who later wrote Moby-Dick. He might have based the character of Queequeg on his memory of Dako. The tour went to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and finally Washington DC, ending in January 1832. Morrell then returned the show to Peale's.

Morrell's second way to make money was his book about his voyages. The company J. and J. Harper agreed to publish it. They hired an experienced writer, Samuel Woodworth, to organize Morrell's notes and sea journals. Woodworth's role as the writer was not made public. Abby Morrell's journals were also helped by another writer, Samuel Lorenzo Knapp. Morrell's book was published in December 1832 and sold very well. The New York Mirror called it "a very interesting and educational work." France's leading explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville praised it, calling Morrell "courageous, skilled and dedicated." However, the explorer and journalist Jeremiah N. Reynolds said the book contained more poetry than truth. Abby's book got less attention. Woodworth also wrote a play called The Cannibals, which opened in New York in March 1833 and was very successful. Morrell's book was one of the sources used by Edgar Allan Poe in his novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym.

Return to the Pacific

With his money problems solved and his new fame, Morrell started planning another trip to the Pacific. He wanted to return Dako to his island and find more trading opportunities. After trying to get money from the government without success, Morrell finally found people to support him. They got him a ship called Margaret Oakley. He sailed from New York on March 9, 1834. Among the crew was Samuel Woodworth's 18-year-old son, Selim Woodworth, whose journals and letters recorded the voyage. Monday was not with them; he had died a year earlier.

Margaret Oakley took the western route to the Pacific, crossing the Atlantic to the Cape Verde Islands, then south to the Cape of Good Hope, and across the Indian Ocean. They arrived near Dako's home islands in November 1834. Dako was welcomed joyfully by his people, as if he had returned from the dead. Morrell stayed in the area for several months, exploring and collecting items. He left in April 1835 for Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) in Australia for repairs and repainting. By June, Morrell was back among the Pacific islands, where he said his final goodbye to Dako. After a useless search for gold on the New Guinea mainland, Morrell took the ship to Canton in China. There, he found valuable cargo for New York, which he expected to bring a profit of $100,000.

After leaving Canton on November 14, Margaret Oakley was delayed in Singapore by bad weather. Some of the cargo was sold there to pay for repairs. The ship left Singapore on December 31, 1835. It was last seen off Mauritius in early February 1836, but then disappeared. It was thought to be lost with all its crew. Months later, news arrived in Mauritius that it had been wrecked on the coast of Madagascar. The crew was rescued, but much of the ship's cargo was lost in the wreck. More cargo was used to pay the rescuers and Morrell's other debts. When representatives of the insurance companies arrived in Madagascar to check the losses, they found that Morrell had left, taking part of the remaining cargo with him. He made his way to South Africa, where he boarded a British ship, Rio Packet, heading for London. Since he was outside US control, the American authorities, who saw his actions as piracy, could not reach him.

Final Years and Death

In London in early 1837, Morrell tried to sell some of the cargo he had taken. But news of his actions had spread, and the money was immediately taken by agents working for Margaret Oakley's insurers. His reputation as a possible fraud prevented him from finding new work. He tried to get a job with the shipping company Enderby Brothers, but Charles Enderby said that "he had heard so much of [Morrell] that he did not think fit to enter into any engagement with him." Stopped in London, Morrell turned his attention to France. He had heard that d'Urville was planning a trip to the Antarctic. On June 20, 1837, he wrote to the French Geographical Society in Paris to offer his help. He wrote: "I will promise to place the Proud Banner of France ten degrees nearer the Pole than any other Banner has ever been planted, if I can get command of a Small schooner... properly manned and equipped." His offer was turned down. Morrell was now seen as a fraud in France, as well as in Britain and America.

It is not known how Morrell supported himself during his months in London. It's possible that Abby sent him money from America. Somehow, in the autumn of 1837, he made his way to Havana in Cuba. After that, his movements are unclear. It seems he eventually became captain of a ship, possibly the Christine. He sailed in September 1838, probably planning to return to the Pacific. He only got as far as Mozambique on the East African coast. His ship was wrecked, and Morrell was stranded ashore. He is reported to have died there, either from a fever or during a local uprising, in late 1838 or early 1839. This story is complicated by another account that says Christine was wrecked a year later, in early 1840. It's not clear if Morrell was alive and in command by that date. Christine was known as a ship that carried slaves, which raises the possibility that Morrell was involved in the slave trade in his final years. Some suggest that Morrell faked his death in Mozambique to avoid the Margaret Oakley's insurers. In this case, he might have escaped to South America and lived there. A letter from August 11, 1843, to a newspaper editor, signed "Morrell," could only have been written by someone who knew a lot about the Oakley voyage.

There is little information about Abby Morrell after 1838. Two records, from 1841 and 1850, place her in New York, but details of her life and death are unknown.

What People Thought of Morrell

Even though Morrell was seen as a fraud after the Margaret Oakley disaster, not everyone criticized him. Some called him "the biggest liar in the Pacific." However, Jules Dumont d'Urville, who had earlier praised Morrell's Four Voyages book, later accused him of making up many of his supposed discoveries. But Jeremiah Reynolds, who had been doubtful about the book, included Morrell's Pacific discoveries in his report to Congress. This was seen as a compliment to the otherwise disgraced sailor.

Later experts and historians have tended to view his career with some understanding. Hugh Robert Mill of the Royal Geographical Society, writing in 1905, believed that a person could be uneducated and boastful, yet still do good work. Mill thought Morrell was "unbearably proud, and as big a braggart as any hero of autobiographical romance," but still found the story itself "very entertaining." Rupert Gould, writing in 1928, thought Morrell might have been boastful but not a deliberate liar. Gould pointed to the accurate information Morrell provided about the discovery of guano deposits on Ichaboe Island, which helped start a successful industry.

William Mills, a more recent expert, agrees that "something useful can be found in Morrell's account, even if much of it must be thrown away." Regarding his Antarctic discoveries, which are Mills's main interest, he notes that Morrell didn't seem to think they were especially important. Morrell didn't claim the discovery of "New South Greenland" for himself but gave credit to Captain Johnson in 1821. In the introduction to his Four Voyages book, Morrell admitted that he included the experiences of others in his story. Paul Simpson-Housley suggests that Morrell might have copied details of his 1823 visit to Bouvet Island from the records of Captain George Norris's visit in 1825, as well as using Weddell's story.

As a reminder of Morrell's short time exploring Antarctica, Morrell Island, located at 59°27'S, 27°19'W, is another name for Thule Island in the Southern Thule group of the South Sandwich Islands. During his Pacific travels, Morrell found groups of islands that were not on his maps. He treated them as new discoveries and named them after various friends in New York – Westervelt, Bergh, Livingstone, Skiddy. One was named "Young William Group" after Morrell's baby son. None of these names are on modern maps, although the "Livingstone Group" has been identified as Namonuito Atoll, and "Bergh's Group" with the Chuuk Islands.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Benjamin Morrell para niños

In Spanish: Benjamin Morrell para niños