Nicolae Ceaușescu facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tovarășul Conducător

Nicolae Ceaușescu

|

|

|---|---|

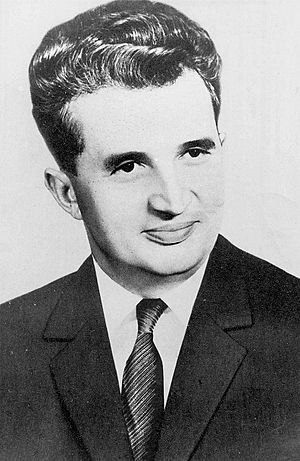

Official portrait, 1965

|

|

| General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party | |

| In office 22 March 1965 – 22 December 1989 |

|

| Preceded by | Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| President of Romania | |

| In office 28 March 1974 – 22 December 1989 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | National Salvation Front Council (interim) |

| President of the State Council | |

| In office 9 December 1967 – 22 December 1989 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Chivu Stoica |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 February 1918 (Old Style: 23 January) Scornicești, Kingdom of Romania |

| Died | 25 December 1989 (aged 71) Târgoviște, Socialist Republic of Romania |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Resting place | Ghencea Cemetery, Bucharest, Romania |

| Political party | Romanian Communist Party (1932–1989) |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Romanian Army |

| Years of service | 1949–1954 |

| Rank | Lieutenant general |

| Battles/wars | Romanian Revolution |

Nicolae Ceaușescu (pronounced chow-SHESK-oo; born 5 February 1918 – died 25 December 1989) was a Romanian communist leader. He was the head of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989. He was also Romania's head of state from 1967, first as President of the State Council and then as President of the Republic. His rule ended in December 1989 during the Romanian Revolution, when he was overthrown and executed. This revolution was part of many anti-Communist uprisings in Eastern Europe that year.

Ceaușescu was born in 1918 in a small village called Scornicești. He joined the Romanian Communist youth movement when he was young. He was arrested several times for his political activities and spent time in prisons during World War II. After the war, he rose through the ranks of the government led by Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. When Gheorghiu-Dej died in 1965, Ceaușescu became the leader of the Romanian Communist Party.

At first, he was popular because he allowed more freedom and openly disagreed with the Soviet Union's actions, like the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. However, his government soon became very strict and controlling. His secret police, called the Securitate, watched people closely and controlled the media. Bad economic decisions in the 1970s led to Romania owing a lot of money to other countries. To pay these debts, Ceaușescu forced the country to export most of its food and goods. This caused shortages and hardship for Romanians.

In December 1989, people protested in Timișoara. Ceaușescu ordered the military to fire on them, which led to many deaths. This made the protests spread across the country, reaching Bucharest. This became known as the Romanian Revolution, which was the only violent overthrow of a communist government during the Revolutions of 1989. Ceaușescu and his wife Elena tried to escape but were caught by the military. They were quickly tried and found guilty of serious crimes against the country, and were executed by firing squad on Christmas Day, 25 December 1989.

Contents

Becoming a Leader: Early Life and Political Journey

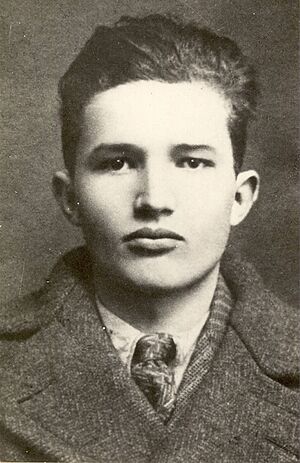

Nicolae Ceaușescu was born in the village of Scornicești, Olt County. He was the third of nine children in a poor farming family. His birth certificate shows he was born on 5 February 1918. He went to primary school and was an average student.

He started as an apprentice shoemaker. His boss was an active member of the Communist Party, which was illegal at the time. Ceaușescu joined the Communist Party in 1932. He was arrested many times as a teenager for street fighting and for collecting signatures for petitions. The secret police called him a "dangerous Communist agitator."

In 1936, he was sentenced to two years in prison for Communist activities. He spent most of this time in Doftana Prison. In 1939, he met Elena Petrescu, who he married in 1946. Elena later became very important in his political life.

During World War II, he was arrested again and spent time in various prisons and camps, including Jilava and Târgu Jiu. In 1943, he was moved to the Târgu Jiu camp, where he met Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. Gheorghiu-Dej became his mentor.

After World War II, the Soviet Union began to influence Romania. Ceaușescu became secretary of the Union of Communist Youth from 1944 to 1945. After the Communists took power in Romania in 1947, Ceaușescu was elected to the Great National Assembly, Romania's new law-making body.

He quickly moved up in the government. In 1948, he became Secretary of the Ministry of Agriculture. In 1949, he was promoted to Deputy Minister. Even without military experience, he was made Deputy Minister of the armed forces with the rank of Major General. He was later promoted to lieutenant general. He even studied at the Soviet Frunze Military Academy in Moscow for two months a year in 1951 and 1952.

In 1952, Gheorghiu-Dej made him a full member of the Central Committee. By 1954, Ceaușescu was a full member of the Politburo, becoming the second most powerful person in the party. As a high-ranking official, Ceaușescu played a role in the forced collectivization of farms, which led to many arrests of peasants.

Ceaușescu's Rule: Leading Romania

When Gheorghiu-Dej died in March 1965, Ceaușescu was chosen as the new leader. He became the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party on 22 March 1965. One of his first actions was to change the party's name back to the Communist Party of Romania. In 1967, he became president of the State Council of Romania, making him the official head of state. His government sent many political opponents to prison or psychiatric hospitals.

Initially, Ceaușescu was very popular in Romania and in Western countries. This was because he followed his own path in foreign policy, often disagreeing with the Soviet Union. In the 1960s, he reduced press censorship. He also refused to join the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by other Warsaw Pact countries. He openly spoke against this action in his famous speech on 21 August 1968. This made Romania seem independent from Moscow.

Ceaușescu wanted to make Romania a major world power. He pursued friendly relations with the United States and Western Europe. Romania was the first Warsaw Pact country to recognize West Germany. It was also the first to join the International Monetary Fund and the first to host a US president, Richard Nixon. Romania even traded with the European Economic Community before other Eastern European countries.

Ceaușescu traveled to many Western countries, presenting himself as a reforming Communist leader. He tried to mediate in international conflicts, like helping to open relations between the US and China in 1969. Romania was also the only country that had good relations with both Israel and the PLO. In 1984, Romania was one of the few Communist countries to participate in the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, even though most Soviet bloc nations boycotted the event.

Ceaușescu continued to focus on making Romania an industrial country. This led to a lot of economic growth and improved living conditions for Romanians at first. Salaries increased, and the state offered free medical care, pensions, and free education.

The July Theses and Increased Control

In 1971, Ceaușescu visited China, North Korea, Mongolia, and North Vietnam. He was very interested in North Korea's Juche idea and China's Cultural Revolution. He admired the strong leadership and personality cults of Kim Il Sung and Mao Zedong. He saw them as leaders who had transformed their countries into major powers.

After returning home, Ceaușescu began to copy North Korea's system. On 6 July 1971, he gave a speech known as the July Theses. This speech called for more control by the Communist Party. It emphasized political education in schools and media. The freedom that had been allowed since 1965 was stopped, and a list of banned books was brought back. This marked the start of a "mini cultural revolution" in Romania, bringing back strict rules for art and writing.

In 1974, Ceaușescu changed his role from president of the State Council to a full executive presidency. This new position made him the country's top decision-maker. He could make many decisions without needing approval from others. From 1974 onwards, Ceaușescu often ruled by decree, meaning his decisions had the force of law. He now held almost all power in the country.

Economic Challenges and Debt Repayment

In the 1970s, oil prices were very high. Romania, which produced oil equipment, benefited from this. Ceaușescu decided to invest heavily in oil-refining plants. His goal was to make Romania Europe's top oil refiner. He borrowed a lot of money from Western banks for this plan. However, a major earthquake in 1977 caused delays. By the early 1980s, oil prices dropped, leading to big financial problems for Romania.

In August 1977, over 30,000 miners went on strike in the Jiu River valley. They were unhappy about low pay and bad working conditions. This was the biggest protest against Ceaușescu's rule before the late 1980s. Ceaușescu met with the miners and reached a compromise. However, many strike leaders later died from accidents or illnesses, leading to rumors that the secret police were involved.

Despite these issues, Ceaușescu continued his independent foreign policy. In 1984, Romania was one of the few communist countries to participate in the Los Angeles Olympics, even though the Soviet Union led a boycott.

Romania was also the first Eastern bloc nation to have official relations with the Western bloc and the European Community. In 1978, Ceaușescu visited the UK and signed a large deal for aircraft production. He was even given a knighthood by Queen Elizabeth II, which was later taken away just before his death.

In 1978, Ion Mihai Pacepa, a high-ranking member of Romania's secret police (Securitate), left the country and went to the United States. This was a major blow to Ceaușescu's government. Pacepa's book, Red Horizons, claimed to reveal details about Ceaușescu's government, including spying on American industries.

Ceaușescu had borrowed over $13 billion from Western countries for economic development. These loans eventually caused huge financial problems for Romania. To fix this, Ceaușescu decided to pay back all of Romania's foreign debts. In 1986, he held a vote to change the constitution, making it illegal for Romania to take foreign loans in the future.

This policy led to economic problems throughout the 1980s. Factories became old, and there were strict limits on how much energy households could use. Food and other goods became scarce. By March 1989, almost all of Romania's foreign debt was paid off. However, this came at a great cost to the Romanian people's living standards.

Protests and Rebellion

In October 1984, a planned coup d'état (a sudden overthrow of the government) failed when the military unit involved was sent to harvest corn instead.

In November 1987, Romanian workers began to protest Ceaușescu's economic policies. A large strike happened in Brașov. Workers were unhappy about low pay, food shortages, and limits on electricity and heating. They chanted slogans like "Down with Ceaușescu!" and "Down with communism!" The secret police and military surrounded the city center and stopped the revolt by force. Many protesters were arrested.

During Ceaușescu's rule, the Romani minority group was largely ignored. They were not included in the list of "co-inhabiting nationalities" and had no representation in the government. This left many Romani people in Romania living in poverty.

The Romanian Revolution and Ceaușescu's Downfall

In November 1989, Ceaușescu was re-elected as leader of the Romanian Communist Party for another five years. During the meeting, he criticized the anti-Communist revolutions happening in other Eastern European countries. However, the very next month, Ceaușescu's own government collapsed after violent events in Timișoara and Bucharest.

The fall of the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia on 10 December 1989 meant that Ceaușescu's Romania was the last strict Communist government in the Warsaw Pact.

The Timișoara Protests

Protests started in the city of Timișoara. They began when the government tried to remove László Tőkés, a Hungarian pastor, who was accused of causing ethnic hatred. Members of his church surrounded his apartment to support him.

Romanian students joined the protest, and it quickly became a general anti-government demonstration. On 17 December 1989, the military, police, and Securitate fired on the protesters, causing many deaths and injuries.

Ceaușescu left for a visit to Iran on 18 December, leaving his wife and subordinates to handle the Timișoara revolt. When he returned on 20 December, the situation was even worse. He gave a televised speech, saying that foreign forces were interfering in Romania's affairs.

Most Romanians had no information about the events in Timișoara from their national news. They learned about the revolt from foreign radio stations and by word of mouth. On 21 December, Ceaușescu organized a large public meeting in Bucharest. Official media said it was a "spontaneous movement of support for Ceaușescu."

Overthrow and Execution

Ceaușescu's Final Speech

The large meeting on 21 December began like many of Ceaușescu's past speeches. He talked about the successes of the "Socialist revolution." However, Ceaușescu had misjudged the crowd's mood. About eight minutes into his speech, people started booing and shouting "Timișoara!" He tried to quiet them, but he couldn't control the crowd. Images of his shocked face as the crowd turned against him were widely shown around the world.

Unable to control the crowd, the Ceaușescus went inside the Communist Party building. The rest of the day saw an open revolt in Bucharest. People gathered in University Square and fought with the police and army. The military cleared the streets by midnight and arrested hundreds of people.

Flight and Capture

By the morning of 22 December, the rebellion had spread to all major cities. The suspicious death of Vasile Milea, Ceaușescu's defence minister, was announced. Believing Milea had been murdered, many soldiers joined the revolution. Ceaușescu tried one last time to speak to the crowd, but they threw stones at him, forcing him back inside. He, Elena, and four others managed to escape by helicopter from the roof, just as demonstrators reached them. The Romanian Communist Party soon disappeared and has never been brought back.

Ceaușescu and Elena fled by helicopter, but they were ordered to land by the army. They were then held by the police and later handed over to the army.

On Christmas Day, 25 December 1989, the Ceaușescus were tried by a special court set up by the new provisional government, the National Salvation Front. They were accused of serious crimes against the country, including misusing state funds and actions that harmed many people. Ceaușescu refused to accept the court's authority, saying he was still Romania's legal president. At the end of the trial, they were found guilty and sentenced to death. The Ceaușescus were immediately executed by firing squad.

The Cult of Personality

Ceaușescu created a strong personality cult around himself. He gave himself titles like "Conducător" ("Leader") and "The Genius of the Carpathians." After becoming President, he even had a "presidential sceptre" made for himself, like a royal symbol. The Communist Party newspaper once published a sarcastic telegram from artist Salvador Dalí congratulating Ceaușescu on his sceptre, not realizing it was a joke.

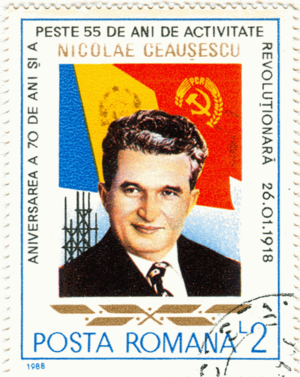

His official birthday, 26 January, was the most important day of the year. Romanian media would be filled with praise for him. People had to appear happy on this day, as looking sad was too risky.

To prevent others from betraying him, Ceaușescu gave important government jobs to his wife Elena and other family members. Romanians joked that he was creating "socialism in one family."

Ceaușescu was very concerned about how he looked in public. For years, official photos showed him looking younger than he was. Romanian state television had strict rules to show him in the best possible way. They also had to make sure his height (he was 1.68 meters tall) was never emphasized. Breaking these rules could lead to severe punishment.

Through Romanian embassies, the Ceaușescus managed to receive many awards and titles from other countries. France gave Nicolae Ceaușescu the Legion of Honour. In 1978, he became a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in the UK, a title that was taken away in 1989. Elena Ceaușescu was also "elected" to a science academy in the US.

During Ceaușescu's rule, the government destroyed many churches and historic buildings in Bucharest to make way for new construction projects. However, a Romanian engineer named Eugeniu Iordachescu managed to save many historic structures by moving them to less visible locations.

Family Life

Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu had three children: Valentin Ceaușescu (born 1948), who was a nuclear physicist; Zoia Ceaușescu (1949–2006), a mathematician; and Nicu Ceaușescu (1951–1996), also a physicist. After his parents' deaths, Nicu Ceaușescu ordered the building of an Orthodox church, which has portraits of his parents on its walls.

Honours and Awards

Ceaușescu was made a knight of the Danish Order of the Elephant, but this award was taken away by the Queen of Denmark, Margrethe II, on 23 December 1989.

Similarly, Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom took away his honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath title the day before his execution. She also returned an award Ceaușescu had given her in 1978.

On his 70th birthday in 1988, Ceaușescu received the Karl Marx Order from Erich Honecker, the leader of East Germany. This was to honor him for not supporting Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms in the Soviet Union.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Nicolae Ceaușescu para niños

In Spanish: Nicolae Ceaușescu para niños