PS Eliza Anderson facts for kids

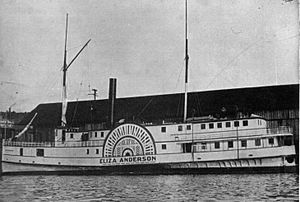

The Paddle Steamer Eliza Anderson was a ship that sailed from 1858 to 1898. She mainly traveled on Puget Sound, the Strait of Georgia, and the Fraser River. For a short time, she also sailed in Alaska. People often called her the Old Anderson. Even though she was known for being slow, people joked that "no steamboat ever went slower and made money faster." The Eliza Anderson played a part in the Underground Railroad, helping someone escape slavery. She also had a very difficult last trip to Alaska during the Klondike Gold Rush.

class="infobox " style="float: right; clear: right; width: 315px; border-spacing: 2px; text-align: left; font-size: 90%;"

| colspan="2" style="text-align: center; font-size: 90%; line-height: 1.5em;" |

|}

Contents

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Eliza Anderson |

| Route | Puget Sound, Strait of Georgia, Fraser River, Admiralty Inlet, Strait of Juan de Fuca, Alaska, Columbia River, |

| Builder | Samuel Farman's yard, foot of Couch Street, Portland, Oregon |

| Laid down | Early 1857 |

| Launched | November 27, 1858 |

| Maiden voyage | January 2, 1859 |

| In service | 1859-1898 (with significant intermediate periods out of service) |

| Out of service | various times, finally beached and abandoned 1898 at Dutch Harbor |

| Fate | Abandoned 1898, Dutch Harbor, Alaska |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | inland steamship |

| Tonnage | 276 |

| Length | 140 ft (43 m) |

| Beam | 25.5 ft (8 m) |

| Depth | 8.8 ft (3 m) depth of hold |

| Decks | three (freight, passenger, boat) |

| Installed power | low-pressure boiler, single-cylinder walking beam steam engine |

| Propulsion | sidewheels |

| Sail plan | schooner (auxiliary) |

- The Expedition Begins

- The Voyage to Alaska

- Overloaded and Missing Equipment

- Running Out of Coal in a Storm

- "Ghost Helmsman" Takes the Wheel

- Safety Reached on Kodiak Island

Building the Eliza Anderson

The Eliza Anderson was launched on November 27, 1858. She was built in Portland, Oregon, for the Columbia River Steam Navigation Company. She was a sidewheeler, meaning she had large paddle wheels on her sides. A low-pressure boiler powered a single-cylinder steam engine to turn these wheels. The ship was made entirely of wood. She was 197 feet long and 25.5 feet wide. Her capacity was rated at 276 tons.

Early Journeys on Rivers and Sounds

Sailing in Canadian Waters

After her first test runs, the Eliza Anderson was sold. A group of owners, including the Wright brothers, bought her. Captain J.G. Hustler brought her to Victoria, British Columbia, in March 1859. At that time, the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush was happening. There weren't enough steamboats in British Columbia.

Because of this shortage, Canadian Governor James Douglas allowed American steamboats to work. They could sail on the route between Victoria and the Fraser River. They had to pay a fee of $12 for each trip. This special permission was called a "sufferance."

First Trips on the Fraser River

The Eliza Anderson arrived at just the right time. She made her first trip to Fort Langley on the Fraser River. This was only one day after she reached Victoria. From Fort Langley, another ship, the Enterprise, took gold seekers further upriver.

By March 30, 1859, the Eliza Anderson had completed two round-trips. She returned to Victoria carrying $40,000 in gold dust. This showed how profitable the gold rush trips were.

By May 1859, three ships were competing on the Fort Langley route. These were the Eliza Anderson, the Beaver, and the Governor Douglas. The Enterprise moved to the Chehalis River. In July, the Eliza Anderson towed the Enterprise to Grays Harbor. But the Enterprise had engine problems. Both ships had to return for repairs.

The Eliza Anderson then picked up miners going to Olympia. She arrived there for the first time on July 9, 1859.

Expanding Service to Puget Sound

Once in Olympia, her owners put her on the Olympia-Victoria mail route. This started in August 1859. John H. Scranton, who had the mail contract, arranged this. Scranton was also known as "Crazy Jack" in the local newspaper.

In September 1859, another ship, the Julia, took over the mail run. The Anderson then returned to the Fraser River route. In mid-September 1859, a wedding was held on the Anderson. It was for Carrie A. Gray and Jacob Kamm, a famous steamboat man. They even received a 13-gun salute.

The Anderson often had "fare wars" with other ships. This meant lowering prices to get more passengers. She fought a fare war with the Canadian steamboat Otter. Fares dropped from $10 to 50 cents per passenger. The Otter had to leave the route. With the Otter gone, fares went back up to $6.

The Julia was not good for winter travel across the Strait of Juan de Fuca. So, on November 1, 1859, the Anderson took over the Olympia-Victoria mail run again. Captain Tom Wright became her new master. In December 1859, the Anderson had a busy schedule. She made one trip to Olympia and one to the Fraser River each week.

She left Olympia every Monday at 7:00 a.m. for Victoria. On Tuesday, she went from Victoria to New Westminster on the Fraser River. She returned to Victoria on Wednesday. On Thursday, she steamed back to Olympia. She rested there until the next week.

On the way down Puget Sound, the Anderson stopped at Steilacoom, Seattle, Port Townsend, and other ports. Fares were $20 per person. Freight cost $5 to $10 per ton. Cattle could be shipped for $15 per head. The Anderson also earned $36,000 a year from the mail contract. She stayed on the Victoria route until 1870. After that, she was a reserve boat until 1877.

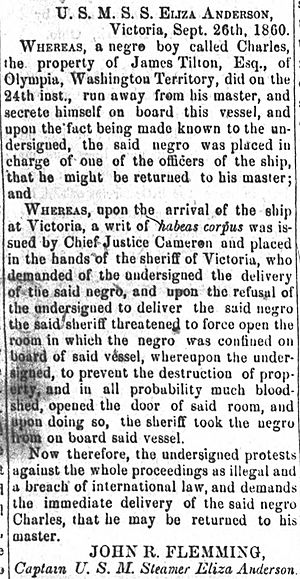

The Underground Railroad and Charles Mitchell

The Anderson played a part in the Underground Railroad. This was a network of secret routes and safe houses. It helped enslaved people escape to freedom. On September 24, 1860, a 14-year-old boy named Charles Mitchell hid on the Anderson. He wanted to reach Canada to escape slavery. Another Black man working on the ship helped him hide.

Charles was found, but he promised to work for his passage. The acting governor, McGill, was also on board. Charles told McGill's son he planned to leave the ship in Victoria. The son told his father, who then told the ship's officers. Just four miles from Victoria, they seized Charles and held him.

In Victoria, people learned Charles was being held. A group of citizens, both Black and white, protested. A lawyer asked the Chief Justice for a writ of habeas corpus. This is a legal order to bring a person before a court. The judge granted the order. The sheriff and a police officer boarded the Anderson. They demanded Charles be released.

After some discussion, Charles was removed from the ship by Canadian authorities. He became a free man. This decision was not popular with some people in Olympia. The local newspaper, the Pioneer Democrat, strongly disagreed with the Canadian court's action.

Charles Mitchell was born in Maryland, a state where slavery was legal. He was enslaved by James Tilton. Even though the Washington Territory was supposed to be free, the local government had said slavery could exist there. The Pioneer Democrat newspaper called Charles a "fugitive slave" in its article. It also printed a protest from Captain Fleming, who described Charles as Tilton's "property."

Mail Route Operations

News of Lincoln's Election

In the early 1860s, there was no telegraph in Puget Sound. Mail carried by steamboat was the fastest way to get news. On November 27, 1860, the Anderson brought important news to Port Townsend. She announced that Abraham Lincoln had been elected president. This news had reached Olympia on November 22.

More Fare Wars

The Anderson's next challenge on the Olympia-Victoria route came from the Enterprise. This ship was built in California in 1861. Her owners brought her north to compete with the Eliza Anderson. But the Wrights, owners of the Anderson, lowered their fare to Victoria to fifty cents. They even offered free meals. This forced the Enterprise off the route after six months.

In February 1862, the Hudson's Bay Company bought the Enterprise. The Andersons owners bought the Enterprises engine. They used it to make their own boat more powerful. Another competitor, the Josie McNear, also failed to beat the Anderson.

A Floating Bank

D.B. Finch, who used to work on the Enterprise, joined the Anderson. He later became a part-owner and captain. Captain Finch was very good with numbers. He became one of the leading bankers in the Washington Territory. He conducted financial business at every stop the Anderson made.

Counties back then often paid their bills with "warrants." These were like paper promises to pay later. Finch bought these warrants cheaply. He paid about 20 cents for every dollar of debt. He eventually collected most of the money owed, plus interest.

The Cassiar Gold Rush

When business slowed down for the Anderson on the Olympia-Victoria route, she was tied up in Olympia. Then, the Cassiar Gold Rush started in northern British Columbia. This seemed like a new chance to make money. The Anderson was repaired enough to make trips as far north as Wrangell, Alaska.

When the Cassiar rush ended, the Anderson returned to Seattle. She stayed there from 1877 to 1883. She eventually sank while tied up at her dock.

Back in Service: 1883 to Early 1890s

In 1883, Captain Wright raised the Anderson from the water. He pumped her out and cleaned her up. He then put her on the route from Seattle to New Westminster, British Columbia. Captain E.W. Holmes was her master.

At this time, the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company wanted to control all transport in Oregon and Washington. This led to another "rate war" with their new ship, the George E. Starr. In April 1884, the Anderson competed hard on the Victoria route. She raced against the Oregon company's large ship, the Olympian.

The Anderson lowered fares to $1.00. She was winning against both the Olympian and Geo. E. Starr. But then, customs officials seized her. They accused her of bringing in immigrants against the Chinese Exclusion Act. Captain Wright eventually cleared his name. However, the Anderson had been off the route for too long. Her competitors had taken all the business.

It was said this broke Captain Wright's heart and his finances. In October 1886, Captain Wright sold the Anderson. The Puget Sound and Alaska Steamship Company bought her. They ran her hard on the Victoria route again. As late as 1888, she even raced another old ship, the tugboat Goliah. The Eliza Anderson last sailed on Puget Sound for the Northwestern Steamship Company.

Dangerous Trips to Alaska

The Anderson was bought by Daniel Bachhelder Jackson. He was setting up the Washington Steamboat Company. Around 1890, the Eliza Anderson was laid up on the Duwamish River. She was not used during financial problems in the early 1890s. She might have rotted away there. But then, gold was discovered in the Yukon Territory.

People looking for gold were willing to travel on almost any ship that floated. So, owners of old ships saw their chance. By this time, the Anderson had been tied up for a long time. She had even been used as a roadhouse and gambling hall.

The Expedition Begins

A group of old ships, later called "floating coffins," was put together. The Eliza Anderson traveled with the strong steam tug Richard Holyoke. The Holyoke towed three other vessels. These were the sternwheeler W.K. Merwin, the old ship Politkosky (now a coal barge), and the yacht William J. Bryant. The Merwin had also been out of service.

The Moran shipyard in Seattle quickly repaired the Anderson. She was back in the water on July 31, 1897. She somehow passed inspection by the hull and boiler inspectors.

The Voyage to Alaska

On August 10, 1897, the Anderson began her trip to Alaska. Captain Thomas Powers was in command. She had about 40 passengers, including some women and children. The plan was to take the whole group of ships to St. Michael. This was the only port near the mouth of the Yukon River. The Anderson would be left there. Then, the Merwin would go up the Yukon to the gold fields.

The Merwin had her funnel and paddlewheel removed for the sea trip. The boat was completely boarded up. Even so, 16 people booked passage on the Merwin. Many thought the inspectors were too hopeful about the Anderson. People said that if she reached St. Michael safely, it would be a miracle.

Overloaded and Missing Equipment

The trip north was a disaster from the start. The Anderson's owners had sold too many tickets. Passengers found much less space than promised. They were so angry they almost threw the purser overboard. Captain Powers had to step in.

Soon after leaving, they found the ship was missing basic equipment, like a compass. Fights broke out among the passengers and crew. When the Eliza Anderson reached Comox, British Columbia, her crew loaded coal badly. The ship veered out of control. She crashed into another ship, the Glory of the Seas. The Anderson had minor damage to one of her paddle guards.

Finally, the ships reached Kodiak, Alaska. This was still a very long way from St. Michael. As the Anderson took on coal, five passengers got off. They refused to get back on. They were sure the Anderson would sink. The small group of ships ran into a storm near Kodiak Island. The Merwin's tow line broke. The Holyoke had great difficulty recovering the Merwin and the 16 people on board.

The Holyoke, Merwin, and Bryant got separated from the Anderson. When they reached Dutch Harbor, they reported her missing. The revenue cutter Corwin went out to search for the missing sidewheeler.

Running Out of Coal in a Storm

The Anderson had run out of coal in the middle of the storm. Her crew had not fully loaded the ship at Kodiak. They had hidden the coal sacks instead of putting them on board. The crew and passengers had to burn wooden parts of the ship. They burned the coal bunkers, cabin furniture, and even cabin walls. Passengers wrote notes to loved ones and threw them overboard in bottles.

"Ghost Helmsman" Takes the Wheel

Just as Captain Powers ordered everyone to abandon ship, a strange thing happened. The lifeboats had been swept away, so abandoning ship would have been hard. But a tale says a tall, ghostly figure with white hair and a beard entered the pilot house. He took the wheel and steered the ship to safety. Some superstitious people said it was the ghost of Captain Tom Wright. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper printed the story from "an old sailor":

Capt. Tom's spirit saw our danger. He knew and loved the Anderson, and that was how it happened that a stranger came out of the storm and brought us safely to land.

It's hard to believe this story. Captain Tom Wright, whose "ghost" supposedly appeared, was still alive in 1897. He did not die until 1906. Still, the story was told among superstitious people for a long time.

Safety Reached on Kodiak Island

Whether a ghost helmsman or not, the ship had to find shelter on Kodiak Island. Luckily, she found an unused cannery on the island. It had 75 tons of coal. (This is where the "Ghost Helmsman" supposedly disappeared.) The Anderson's crew quickly took this coal. With it, the boat was able to reach Dutch Harbor.

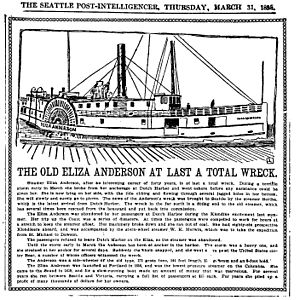

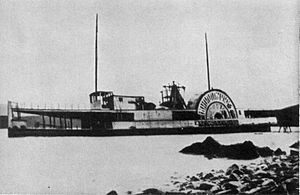

Abandoned and Lost Forever

At Dutch Harbor, the Anderson had a steam pipe explosion. She also collided with a dock. Her passengers left her. They moved to a steam schooner to reach the mouth of the Yukon River. The Anderson stayed tied up at Dutch Harbor until March 1898. Then, a storm washed her onto a beach. She slowly broke apart there.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote about her fate on March 31, 1898:

The old Eliza Anderson, after an interesting career of 40 years, is at last a total wreck. During a terrible storm early in March she broke from her anchorage at Dutch Harbor and went ashore before any assistance could be given her. She is now lying on her side, with the tide ebbing and flowing through several jagged holes in her bottom. She will surely and slowly go to pieces. The news of the Anderson's wreck was brought to Seattle by the steamer Bertha. ... The wreck in the far north is a fitting end to the steamer, which has several times been rescued from the boneyard and put back into commission.

Mystery of the Ghost Helmsman Solved

In 1956, Thomas Wiedeman, Sr., who was on the Anderson's last Alaska trip, wrote an article. He said that in 1953, he met Joe Braddock of San Francisco. Braddock had been a crewman on the Corwin, the ship that searched for the Anderson in 1897.

Braddock told Wiedeman that he had questioned two brothers, Erik and Olaf Heestad, on Kodiak Island. They ran the cannery where the Anderson found coal. When the Anderson left Kodiak, Erik had hidden on board. He hoped to get to Dutch Harbor to ask an uncle for a loan. He was afraid of being discovered. He hid until the Anderson was in such bad trouble that only he could save the ship.

Once they reached safety, his brother Olaf rowed out from shore and took him off the ship. They stayed in their remote cabin. They waited until the Anderson finally got more coal and left for Dutch Harbor. This explained the "ghost" story.

Images for kids

-

Eliza Anderson as the vessel appeared after reaching Dutch Harbor.