Palencia mining basin facts for kids

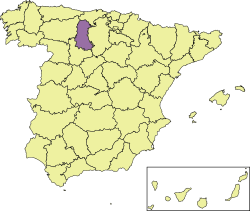

The Palencia mining basin was a Spanish area where people dug for coal. It is located in the northern part of Palencia province, in a mountainous region called Montaña Palentina. The main types of coal found here were black coal and anthracite.

Coal was first found here in 1838, near the towns of Orbó and Barruelo. This discovery completely changed the way people lived and worked in the region. Mining became the main way to earn a living. It also led to new ways to transport the coal, like the La Robla Railroad.

This area was a very important source of energy for Spain in the 1950s. But from the 1960s, other fuels started to replace coal. When Spain joined the European Economic Community in 1986, many mines that weren't making money had to close. By the 1990s, most mining stopped. The last mines, two underground ones in Velilla del Río Carrión and two open-pit mines in Guardo and Castrejón de la Peña, closed in 2014.

Almost 200 years of mining greatly changed the natural landscape, the number of people living there, the economy, and the culture of the area.

Contents

- Exploring the Mining Area

- How the Earth Formed the Coal

- The Science of Coal

- Mining Through the Years

- Important People from Mining History

- Main Mining Operations

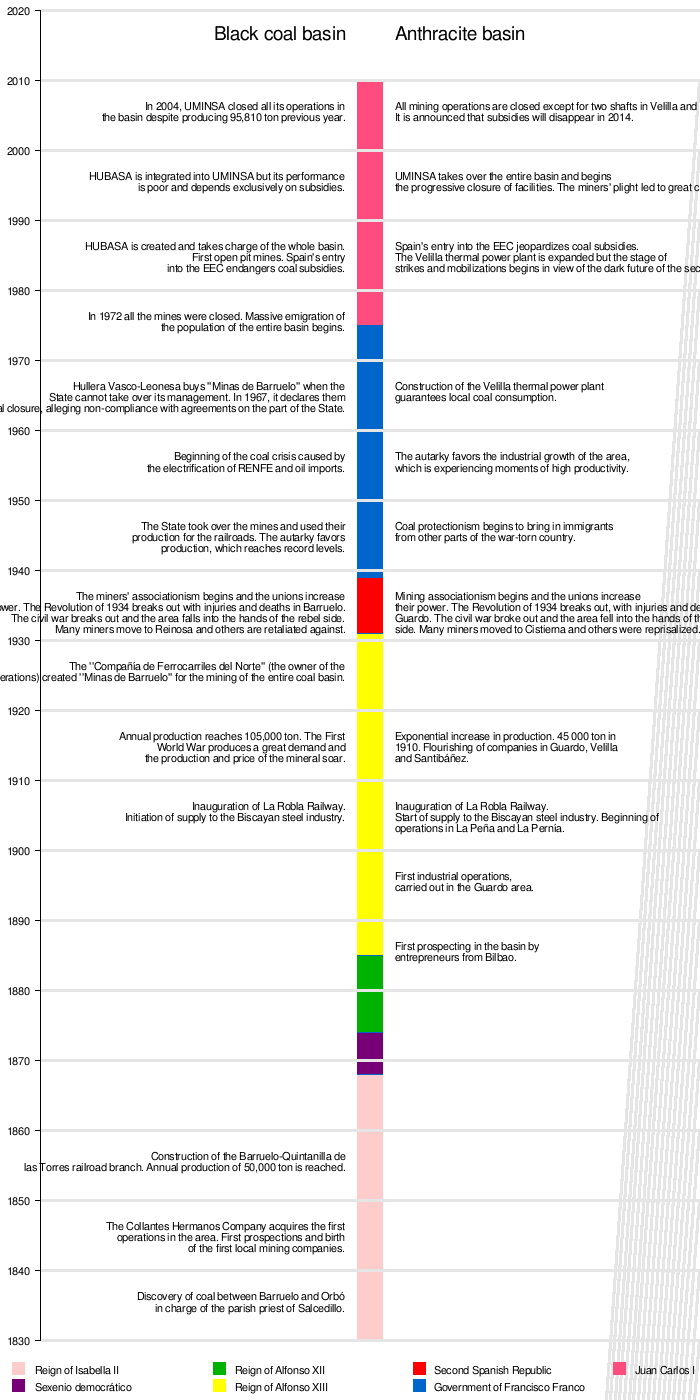

- Timeline of Mining in Palencia

- Images for kids

- See also

Exploring the Mining Area

Mountains and Rivers

The Montaña Palentina is a region known for its mountains. It's part of the Cantabrian Mountain Range. The area has deep river valleys and high mountains. Some of the tallest peaks are Curavacas (2520 meters high) and Espigüete (2450 meters high).

Two important river basins are in this area. The Douro basin has the Carrión and Pisuerga rivers. The Ebro basin also crosses a small part of the region.

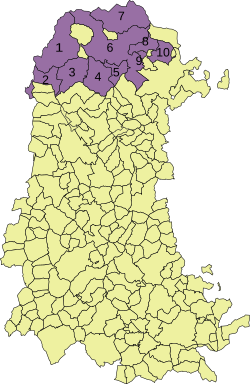

Mining Zones

An early historian, Ricardo Becerro de Bengoa, divided the Palencia mining area into three parts in 1874:

- Rubagón basin: Around the Rubagón river, with Barruelo de Santullán and Orbó as main towns.

- Carrión basin: Near the Carrión river, including mines in Guardo, Velilla del Río Carrión, and Santibáñez de la Peña.

- Pisuerga basin: Mines north of Cervera de Pisuerga, mainly in La Pernía and San Salvador de Cantamuda.

These divisions are still used today.

Types of Coal Found

Black Coal

Black coal is mostly found around the Santullán valley, especially near Barruelo. Studies from the 1800s showed many layers of black coal in this area. These layers were about one meter thick. It was estimated that there were about 75 million tons of black coal here.

Anthracite

Anthracite coal is found in the northwest of the province, from the border with León province to Cervera de Pisuerga. This area is a narrow strip of land. It includes towns like Velilla del Río Carrión, Guardo, Santibáñez de la Peña, Castrejón de la Peña, and Dehesa de Montejo. Further north, more anthracite was found around La Pernía.

This area was thought to have ten to twelve layers of anthracite, each about one meter thick. There were an estimated 85 million tons of anthracite.

How the Earth Formed the Coal

General Geology

The Palencia mining basin is located in a geological area called the Pisuerga-Carrión Unit. This is the eastern part of the Cantabrian Area.

The rocks here are very old, from the Paleozoic era. The coal itself formed during the Carboniferous period. This period lasted for about 55 kilometers from southwest to northeast across northern Palencia. The rocks from this time show many changes in how they were formed.

The coal basins were folded and shaped by powerful earth movements. However, the black coal and anthracite basins formed in different ways.

Geology by Area

Black Coal Basin

The black coal basin formed during the Westphalian B phase of the Carboniferous period. The coal here formed in areas that were once river deltas, with layers of marine deposits mixed with land-based layers containing coal.

Anthracite Basin

The anthracite basin formed later, during the Westphalian D period. Unlike the black coal basin, this area was mostly influenced by land, not the sea. Its layers of rock are a mix of land-based and marine sections.

The anthracite belt was created by the Alpine mountain-building movement. This movement folded the land, creating a fault where the anthracite deposits are found.

The Science of Coal

Studies show that the coal from the Guardo-La Pernía area is anthracite. This means it has a high carbon content and burns very hot. The high temperatures and pressure from earth movements helped turn this coal into anthracite.

The coal from the Santullán valley and Rubagón basin is black coal. This type of coal is an organic sedimentary rock. It forms when lignite (a softer coal) is put under great pressure.

Mining Through the Years

History of Mining

Early Days

Two main things led to the start of mining in Palencia. First, the Industrial Revolution created a huge need for coal to power new machines like the steam engine. Second, new mining laws in Spain made it easier for private companies to own and operate mines.

In Spain, coal mining first started in Asturias. Engineers studied the land to find coal deposits. By the late 1830s, the first mining companies began to appear.

First Discoveries

- Black Coal Basin

The discovery of coal in Montaña Palentina is often credited to a priest named Ciriaco del Río in 1838. He found black stones between Orbó and Barruelo. When he saw that they burned and held heat, he realized it was coal. He then contacted a mining company to start digging.

The first company to mine coal here was Collantes Hermanos Company in 1846. Later, in 1856, Crédito Mobiliario Español took over. At first, coal was moved by animal carts to Alar del Rey, then by barges on the Canal de Castilla. This was expensive. So, a railway branch was built from Barruelo to Quintanilla de las Torres. It opened in 1863. This railway helped Barruelo coal compete with coal from other areas. Production grew to 53,740 tons in 1865, making Palencia the second-largest coal producer in Spain.

- Anthracite Basin

Anthracite mining started later in Palencia. It really grew after the La Robla Railroad was built. Productive mining began around 1895, with a company called Sociedad Euskaro-Castellana working in Guardo. By 1900, mining also started in Villaverde de la Peña, La Pernía, and Castrejón de la Peña.

From 1908, Sociedad Minera San Luis took over the mines in Guardo and became the main company there. Another big anthracite center, Velilla del Río Carrión, also grew in importance.

- La Robla Railway

The La Robla Railroad was a huge boost for mining in Palencia. It was built because the steel industry in Biscay needed a lot of coal. Transporting coal by sea was too expensive. So, a railway was needed to connect the coal mines in Palencia and León province to the steel factories.

Several plans were made in the late 1800s. The final project, linking La Robla (León) and Balmaseda (Biscay), was designed by engineer Mariano Zuaznavar. He convinced businesses to invest. The railway was built very quickly. The main section opened in 1894, just four years after construction began. This railway was key for moving coal.

| 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Coal | 105 000 | 98 000 | 110 000 | 105 000 | 140 000 | 135 000 | 130 000 | 120 000 | 105 000 | 125 000 | |||

| Anthracite | 24 000 | 23 000 | 8000 | 10 000 | 12 000 | 32 000 | 45 000 | 47 000 | 62 000 | 62 000 | |||

The Boom Years

The First World War (1914–1918) caused a big increase in coal production in Spain, especially in Palencia. Countries needed more coal because they couldn't get it from big producers like the United Kingdom. This, along with better transport like La Robla railroad, made the mining sector boom. Prices for coal went very high. Anthracite production jumped from 63,906 tons in 1914 to 228,762 tons in 1918. Many important mining companies grew during this time.

The Barruelo coal basin continued to produce coal mainly for the locomotives of the Compañía de Ferrocarriles del Norte, which owned the mines. In 1922, this company created Minas de Barruelo to manage all the coal mining in the area. This basin was not much affected by the economic problems after the war because it kept selling coal to the railways.

Workers' Rights and Conflict

- Early Unions

Working conditions in the mines in the early 1900s were very difficult. Workers started forming groups to demand better conditions. These groups, called unions, became very important, especially the Sindicato Minero Castellano of the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), which supported socialist ideas.

By the late 1920s, unions were strong in Barruelo and Guardo. In September 1933, a big mining strike happened in the region. Almost all 3500 miners joined, demanding better working conditions. The strike lasted 24 days, and the miners' demands were met.

- Revolution of 1934

In 1934, there were serious problems in northern Palencia. Miners in Barruelo and Guardo protested and took control of their towns. There were clashes, and some people died. The army was sent in, and the miners eventually surrendered. Many workers were arrested, and union leaders were removed from their positions. This led to a big reduction in the number of miners working in the industries by the end of 1935.

- Civil War

Because of the repression against miners and unions, the Civil War (1936-1939) did not have a huge impact on the area directly, as it quickly came under the control of the rebel side. Many miners fled to the mountains to fight for the Republican side.

After the war, miners faced harsh consequences for their actions in 1934. Many residents were killed during this time. The mining community had to endure a period of strict control until the 1960s.

The Autarky Period

The autarky policy of Franco's regime meant Spain had to rely on its own resources. Coal became the main energy source, which helped the Palencia basin grow a lot in the 1950s. However, the mining industry didn't modernize, which set the stage for its future problems.

After the war, the Barruelo mines became state-owned, managed by RENFE (the national railway company). Coal was used to power steam locomotives. But when RENFE started electrifying its lines, the coal region lost its main customer. This, along with new energy imports, made it hard for the mines to survive, so the state decided to sell them to private companies.

- The Velilla Power Plant

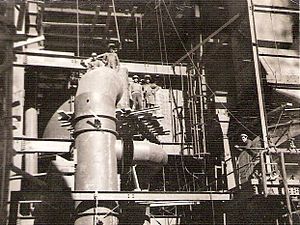

A plan to build a thermal power plant in the area started in the late 1950s. The goal was to use the coal produced in the basin. The company Iberduero built the plant near the Carrión River in Velilla del Río Carrión. When it opened in 1964, the power plant became the biggest buyer of Palencia coal. It used up to 80% of some mining companies' production. In its first year, the plant used 222,169 tons of coal.

The Decline

In 1966, the Hullera Vasco-Leonesa Mining Company bought the Barruelo mines. They planned to improve productivity. But in 1967, the company claimed the state didn't keep its promises and asked to close the mines and fire all workers. Despite the big economic impact, all operations in the area closed between 1969 and 1972. This led to many people moving away. In 1980, a new company, Hullas de Barruelo, S. A. (HUBASA), tried to restart operations with 50 workers.

| Mining Companies and Employees in 1980 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | Location | Number of miners | |||||||||||

| Antracitas de Velilla | Velilla del Río Carrión | 268 | |||||||||||

| Sociedad Minera San Luis | Guardo | 132 | |||||||||||

| Minas de San Cebrián | San Cebrián de Mudá | 119 | |||||||||||

| Cántabro Bilbaína | Santibáñez de la Peña | 103 | |||||||||||

| Antracitas de San Claudio | Castrejón de la Peña | 82 | |||||||||||

| Floreal Llorente | Santibáñez de la Peña | 70 | |||||||||||

| Antracitas Valdehaya | Guardo | 56 | |||||||||||

| Hullas de Barruelo | Barruelo de Santullán | 50 | |||||||||||

| Antracitas Mina Eugenia | San Salvador de Cantamuda | 33 | |||||||||||

| González Tejerina | Redondo-Areños | 25 | |||||||||||

| Nemesio y José | Santibáñez de la Peña | 16 | |||||||||||

| Carbones San Isidro y María | Guardo | 13 | |||||||||||

| Felipe Villanueva | Dehesa de Montejo | 7 | |||||||||||

| Antracitas del Campo | San Salvador de Cantamuda | 7 | |||||||||||

| TOTAL | 981 | ||||||||||||

When Spain joined the European Economic Community in 1986, it meant many mines had to close because the Community policy aimed to stop supporting mines that weren't profitable. This led to many strikes and protests from miners trying to save their jobs. In May 1988, there were big protests in Palencia, with miners blocking roads and railways.

In 1989, the European Commission decided to reduce aid for coal mining. This meant mines had to cut production or close. The Bergel Group, a mining company, went bankrupt in 1990. This caused three mines in Palencia to close and 328 workers to lose their jobs.

| Anthracite Production in the 1970s and National Percentage (Thousands T) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | ||||

| Palencia | 317 | 358 | 373 | 376 | 359 | 374 | 390 | 390 | 367 | 368 | |||

| Spain | 2 808 | 2 876 | 3 013 | 2 889 | 2 948 | 3 154 | 3 548 | 3 768 | 3 801 | 3 645 | |||

| % Palencia | 11,2 | 12,4 | 12,3 | 13,0 | 12,1 | 11,8 | 10,9 | 10,3 | 9,6 | 10,0 | |||

The End of Mining

Mining facilities in Montaña Palentina closed gradually after 1990. New open-pit mines started in Guardo and Velilla del Río Carrión. However, many people opposed these open-pit mines, saying they harmed the environment. In Guardo, an "Anti-Cutting Platform" even became a political group.

In 1998, Hullas de Barruelo became part of Unión Minera del Norte (UMINSA), a large mining group. The Barruelo mines relied heavily on government money. After cuts to these funds, UMINSA closed its last facility in the coal mining area in 2005. Its 40 workers moved to another mine.

By 1999, UMINSA had taken over almost all remaining mining companies in the Palencia basin. At that time, 635 workers were employed, producing 520,000 tons of coal per year.

However, UMINSA continued closing mines. In 2003, it closed the last shaft of San Luis in Guardo. In 2004, more shafts closed. In Velilla del Río Carrión, the "El Abuelo" mine closed in 2007, leaving only the Las Cuevas shaft active.

Future Hopes

By 2009, the only active underground mines in Palencia were in Velilla del Río Carrión: "San Isidro" and "Las Cuevas". "Las Cuevas" was considered one of the most modern mines in Europe. However, both mines stopped working in 2014. UMINSA also owned two open-pit mines near Muñeca de la Peña and Traspeña de la Peña.

The future of mining was uncertain. The European Union planned to end government support for unprofitable mines by 2014. This worried many people in Palencia, as it meant all mines might close.

In 2010, UMINSA stopped paying miners' salaries due to financial problems. On September 2, 52 miners started a protest inside the Las Cuevas shaft. They stayed there for 27 days, demanding a solution. They left when the European Commission allowed the Spanish government to support power companies that used local coal. The deadline for these subsidies was later extended to 2018.

| 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracite | 349 909 | 212 671 | 366 056 | 386 729 | 348 822 | 321 692 | 285 018 | 357 022 | 451 686 | 415 962 | |||

| Black Coal | 127 094 | 120 451 | 115 640 | 112 800 | 98 270 | 107 293 | 95 810 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

Where the Coal Went

The coal from Palencia was used for different things over the years. When La Robla railroad opened in 1894, most of the coal went to the steel industry in the Basque Country.

| 1895 | 1897 | 1899 | 1901 | 1903 | 1905 | 1907 | 1909 | 1911 | 1913 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tons | 17 378 | 48 906 | 107 413 | 163 381 | 135 811 | 128 694 | 189 248 | 140 556 | 163 552 | 223 629 | |||

In the 1950s, during the autarky, coal use diversified. In 1950, 24% went to railroads, 12% to thermal power stations, and 10% for home use.

In 1958, La Robla train carried a record 908,464 tons of coal. From 1964, the Velilla thermal power plant became the main buyer of Palencia coal. In its first year, it used 222,169 tons. By 1968, almost half of Palencia's coal went to this plant.

The end of steam locomotives and changes in the steel industry meant less demand for coal. In 1984, the Velilla power plant expanded, but it also started buying imported coal. By 2008, the plant was still allocated 450,000 tons of coal from UMINSA, which was more than the entire basin produced in 2007.

Working Conditions in the Mines

Working in the mines was very dangerous, especially in the early years. Accidents were common. The worst accident happened in the famous Pozo Calero de Barruelo on April 21, 1941. An explosion killed 18 miners and injured 19. The "Calero" mine, which closed in 2002, had a sad record of about 12 deaths per year. For a time, the Barruelo mines were considered the most dangerous in Spain.

In the anthracite mines, there was no dangerous gas like firedamp. Most accidents were due to collapses in the tunnels. Between 1956 and 1997, 116 miners died in this area from work accidents.

Miners also suffered from a serious lung disease called silicosis. This disease is caused by breathing in silica dust for a long time. A study in 1980 found that between 1973 and 1978, 832 cases of silicosis were diagnosed in the Palencia basin. This shows how common and serious this disease was among miners.

Mining's Impact on the Region

Changes to the Environment

Coal mining has left its mark on the Montaña Palentina. Large piles of waste rock (dumps) and abandoned mine structures are common sights. People are now trying to turn these sites into tourist attractions to preserve their history.

Open-pit mining has had a big impact on the environment. The first open-pit mine in Barruelo in 1993 was called an "ecological disaster." In the 1980s, people in Guardo protested against open-pit mining. In 2006, UMINSA proposed a large open-pit mine in Guardo, but the town council rejected it to protect its forests.

A 1988 report said that open-pit mining caused severe environmental damage. This included pollution from waste, runoff from dumps, and the loss of plants. The Corcos mountain in Guardo, which had a large forest, was greatly affected by mining. The Rubagón river also suffered from pollution.

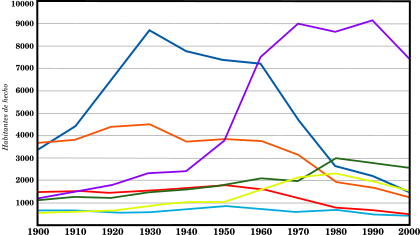

Population Changes

The mining industry greatly affected the population of the towns in the area.

| 1837 | 1850 | 1877 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1970 | 1991 | 2001 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barruelo de Santullán | 30 | 36 | 3 255 | 3 389 | 4 417 | 6 600 | 8 695 | 7 770 | 7 372 | 4 724 | 2 193 | 1 641 | 1 488 |

| Castrejón de la Peña | 169 | 177 | 1 301 | 1 492 | 1 541 | 1 456 | 1 532 | 1 666 | 1 789 | 1 209 | 772 | 613 | 486 |

| Cervera de Pisuerga | 660 | 784 | 1202 | 1 555 | 1 268 | 1 237 | 1 485 | 1 594 | 1 815 | 1 997 | 2 953 | 2 684 | 2 566 |

| Guardo | 436 | 625 | 1 014 | 1 216 | 1 506 | 1 801 | 2 343 | 2 427 | 3 757 | 9 012 | 9 458 | 8 548 | 7 400 |

| La Pernía | 116 | 114 | 621 | 611 | 630 | 591 | 589 | 738 | 836 | 600 | 539 | 471 | 423 |

| Santibáñez de la Peña | 58 | 94 | 3 235 | 3 669 | 3 823 | 4 410 | 4 500 | 3 760 | 3 872 | 3 147 | 1 912 | 1 500 | 1 266 |

| Velilla del Río Carrión | 264 | 385 | 497 | 542 | 589 | 662 | 876 | 1 032 | 1 048 | 2 125 | 2 103 | 1 767 | 1 521 |

Note: The colored cells show the highest population numbers reached by each town. The color matches the graph on the right.

Economic Changes

Before coal mining, the area's economy was based on farming and raising animals. With mining, many people started working in the mines. This made mining the main economic activity in Montaña Palentina for most of the 20th century. Besides direct mining jobs, many other jobs were created to support the mines and transport coal. During the 1950s boom, many shops and entertainment places also opened.

As mines closed, the government tried to help the economy with plans like the Coal Mining and Alternative Development Plan. However, these plans haven't stopped people from moving away from the region.

Social Changes

Mining greatly changed the society of the region. People who used to farm or raise animals started working in the mines.

Mining companies had a big influence. In the mid-1800s, they built houses for workers and set up services like schools and savings banks. This meant the companies had a lot of control over the towns.

Workers also started forming associations to protect their rights. The first union, La Unión, was created in Barruelo in 1900. These associations played a big role in events like the Workers' Revolution of 1934.

After the Civil War, many people moved to the mining areas from other rural parts of Spain. But in the 1960s, as mining declined, many young people moved away to find jobs in industrial areas like Biscay.

Today, many former mining towns have mostly older people and retirees. This is because young people left for better job opportunities, and many miners took early retirement. This has further reduced the number of working people in the area.

Cultural Heritage

To preserve the history of mining in Palencia, the Mining Interpretation Center opened in Barruelo de Santullán in 1999. It has a mine you can visit, a cultural center, and a museum. The museum shows the technical and human side of mining from its discovery in 1838 until its closure in 2005. About 22,000 people visited the museum in its first year.

In Velilla del Río Carrión, a National Mining Shoring Contest has been held since 2007. This contest is part of the mining festival on Saint Barbara's Day (December 4). It's a competition where people build wooden frames, like those used to support tunnels in a mine. They are judged on how well and how fast they build them.

There are also important books about Palencia's mining history. These include El Pozo Calero. Historia de la minería en el Valle de Santullán (2003) and Mineros y minas. Historia del carbón de antracita en la Montaña Palentina (2010).

Important People from Mining History

- Ricardo Becerro de Bengoa (1845–1902): A scientist and historian who wrote about the start of mining in Palencia. He shared the story of the priest Ciriaco del Río discovering coal.

- Manuel Llaneza (1879–1931): A socialist union leader. He worked in the Barruelo mines from age 11 to 23. A street in Barruelo is named after him.

- Mariano Ortega Alonso (1919–1951): A miner from Barruelo who became a leader of anti-Francoist fighters in the area.

- Claudio Prieto (1934–2015): A composer born in Muñeca de la Peña. He started his musical journey in the Municipal Band of Guardo.

- José María Cuevas (1935-2008): A well-known businessman. He was born after his parents had to leave Barruelo de Santullán due to social unrest.

- Pedro Miguel Barreda Marcos (1931–2016): A historian and journalist who wrote a lot about Palencia's history, including its mining past.

- Faustino Narganes Quijano (1948): A historian who lived through the mining boom years. He wrote important studies and a book about anthracite mining in Montaña Palentina.

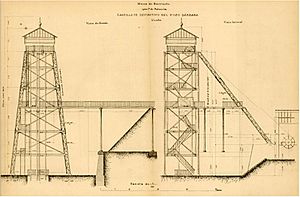

Main Mining Operations

| Main Mining Shafts | ||||||

| Name of the shaft | Municipality | Substance | Location | Opened | Closed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pozo Peragido | Barruelo de Santullán | black coal | 42°54′03″N 4°16′30″W / 42.900833°N 4.275°W | 1936 | 2005 | Closed in 1969 and reopened in 1983. |

| Pozo Bárbara | Barruelo de Santullán | black coal | 42°53′56″N 4°16′37″W / 42.898889°N 4.276944°W | 1878 | 1890 | Abandoned when expectations were not met. |

| Pozo Calero | Barruelo de Santullán | black coal | 42°54′46″N 4°18′20″W / 42.912778°N 4.305556°W | 1911 | 2002 | Closed in 1972 and reopened in 1994 |

| Pozo María del Carmen | La Pernía | anthracite | 43°00′03″N 4°25′44″W / 43.000833°N 4.428889°W | 2004 | Montebismo Group. Closed by UMINSA. | |

| Mina Eugenia | La Pernía | anthracite | 42°59′48″N 4°30′47″W / 42.996667°N 4.513056°W | 1950 | 1992 | Lores. In 1992, the company ceased operations. |

| Pozo Pedrito Segundo | Castrejón de la Peña | anthracite | 42°49′31″N 4°37′04″W / 42.825278°N 4.617778°W | 1965 | 1996 | Villanueva. Flooded by the rupture of an aquifer. |

| Pozo Peruscales | Santibáñez de la Peña | anthracite | 42°49′31″N 4°41′44″W / 42.825278°N 4.695556°W | 2004 | Villaverde de la Peña. Closed by UMINSA. | |

| Pozo Valdeabuelo | Santibáñez de la Peña | anthracite | 42°48′21″N 4°44′36″W / 42.805833°N 4.743333°W | 1985 | Affected by the closure of the Bergel Group. | |

| Pozo El Abuelo | Velilla del Río Carrión | anthracite | 42°50′52″N 4°52′41″W / 42.847778°N 4.878056°W | 2007 | El Abuelo Group. Closed by UMINSA. | |

| Pozo Las Cuevas | Velilla del Río Carrión | anthracite | 42°50′53″N 4°52′44″W / 42.848056°N 4.878889°W | 2014 | El Abuelo Group. Closed by UMINSA. | |

| Mina Trueno | Guardo | anthracite | 42°47′19″N 4°53′02″W / 42.788611°N 4.883889°W | 1895 | 1966 | Mount Corcos. Closed by Sdad. Minera San Luis. |

| Pozo Sestil | Guardo | anthracite | 42°48′08″N 4°53′40″W / 42.802222°N 4.894444°W | 2003 | Mount Corcos. Closed by UMINSA. | |

Timeline of Mining in Palencia

Images for kids

-

A column of Civil Guards with miners captured in the nearby mountains crosses Brañosera towards Barruelo de Santullán, on 8 October 1934.

See also

In Spanish: Cuenca minera palentina para niños

In Spanish: Cuenca minera palentina para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |