Prehistory of Siberia facts for kids

Siberia's ancient past is full of different groups of people, each with their own unique ways of life. In the Copper Age, people in western and southern Siberia were mostly herders, moving their animals around. But in the eastern forests and cold northern lands, people were hunter-gatherers for a very long time. Around 1000 BC, big changes happened in Central Asia. People started to become nomads, riding horses and moving across the vast steppes.

Contents

Exploring Ancient Siberia

Learning about Siberia's past started a long time ago. Peter the Great, a Russian ruler, ordered people to collect ancient gold treasures. This saved many items from being melted down. Later, explorers like Vitus Bering went on big trips to study Siberia's land and people. They also started digging up ancient burial mounds called kurgans.

After a quiet period, archaeological research really picked up in the late 1800s. After the October Revolution in 1917, even more digging happened, especially when huge building projects uncovered old sites. Eventually, even very remote places like Sakha and Chukotka were explored. Since 1991, scientists from all over the world have worked together to learn more about Siberia's amazing history.

Siberia's Diverse Lands

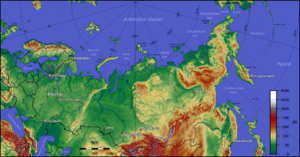

Siberia is a huge place with many different climates and landscapes. To the west are the Ural Mountains. From there, flat lands stretch all the way to the Yenisei River. Beyond that are highlands, then the Lena River basin, and even more highlands in the northeast. To the south, Siberia has a chain of mountains and hills.

The weather in Siberia can be extreme! Yakutia is one of the coldest places on Earth. Temperatures can swing from super cold in winter (like -50°C) to warm in summer (over +20°C). Not much rain falls there, or in the dry steppes and deserts to the southwest.

Today, farming without extra water is only possible in a certain band of Siberia. This is why Siberia has different natural areas:

- Tundra: In the far north, with very little plant life.

- Taiga: The largest part of Siberia, covered in northern coniferous forests.

- Forest-steppe: In the southwest, where forests meet grasslands.

- Grass steppes and deserts: Further south, dry grasslands and deserts.

About 12,000 years ago, during the last ice age, the tundra stretched much further south. Big ice sheets covered the Urals and areas near the Yenisei River.

A Look at Siberia's Past

The Stone Age (Paleolithic to Neolithic)

The earliest signs of people in Siberia go back to the Lower Stone Age. In the Upper Stone Age, many remains are found in the Urals, Altai Mountains, and near Lake Baikal. People even lived north of the Arctic Circle about 25,000 years ago!

At a place called Mal'ta near Irkutsk, scientists found remains of huts. They also found small sculptures of animals and women, similar to those found in Europe. These early Siberians were hunter-gatherers, hunting huge mammoths and reindeer, and catching fish.

Around 5500-3400 BC, the Neolithic (New Stone Age) began in North Asia. This period is mostly known for the invention of pottery. Unlike in Europe, people in Siberia didn't start farming or herding during this time. Their lifestyle didn't change much, but they started making pots!

In southwest Siberia, the Chalcolithic (Copper Age) began around 3000 BC. This is when people started working with copper. But in the northern and eastern parts of Siberia, life stayed pretty much the same.

The Bronze Age (about 2400–800 BC)

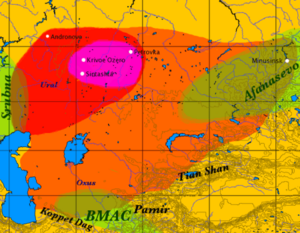

Around 2500 BC, people in western Siberia learned how to work with bronze. Groups living near the Ural Mountains developed the Andronovo culture. They built some of the earliest "cities" in Siberia, like Arkaim and Sintashta.

By the Middle Bronze Age (about 1800–1500 BC), the Andronovo culture spread far to the east, even reaching the Yenisei River. They made similar types of pottery across this huge area.

In the Late Bronze Age (about 1500–800 BC), big changes happened in southern Siberia. The Andronovo culture faded, and new groups emerged with different pottery and bronze tools. In the Baikal region, people who had been hunter-gatherers started herding animals and using bronze for the first time.

The Ymyakhtakh culture (about 2200–1300 BC) was a very widespread culture in Siberia during the Late Neolithic. It started in the Lena and Yenisei river areas and spread both east and west.

The Iron Age (about 800 BC - AD 500)

The Iron Age began in Siberia around 1000 BC. In western Siberia, the local pottery styles continued. But in the Central Asian steppes, a huge change happened. The settled herding societies were replaced by mobile horse nomads. These groups could move quickly across the steppes, and they became very powerful.

These nomads often threatened settled civilizations. For example, the Xiongnu threatened ancient China, and the Huns later challenged the Roman Empire. We know about these changes from archaeological finds. Settlements became rare, and important leaders were buried in rich kurgans (burial mounds). New styles of art also appeared.

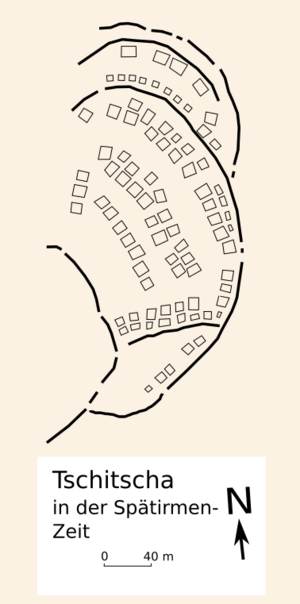

In the wetter steppes to the north, settled herding cultures continued, but they were influenced by the nomads. Some proto-urban (early city-like) settlements, like Tshitsha, existed in western Siberia.

Later Periods

After the Iron Age, it's harder to track changes in some areas because there's less archaeological evidence. Around the 5th century AD, Turkic peoples appeared in the Central Asian steppes. Over time, they spread north and west, taking control of southern Siberia. The northern parts of Siberia, where people spoke Uralic languages and Paleosiberian languages, are still not well understood.

The next big change in Siberia's history was the arrival of the Russians. They started expanding eastward in the 1500s, a process that continued until the 1800s. This marked the beginning of modern times in Siberia.

Ancient Siberian Cultures

Early Hunter-Gatherers

The oldest archaeological finds in Siberia are from the Lower Stone Age. Many ancient sites were used for hundreds of years. People lived in tents or huts dug slightly into the ground, with walls and roofs made of animal bones and antlers. Their tools were mostly made from flint, slate, and bone.

Some settlements have early artworks, like sculptures of humans, animals, and abstract shapes. These early Siberians were hunter-gatherers, relying on mammoths, reindeer, and fish for food.

Around 6000 BC, pottery spread across Siberia. This marks the start of the Siberian Neolithic. But unlike other parts of the world, this didn't mean a big change in how people lived or got their food.

Hunter-Gatherers in Yakutia and Baikal

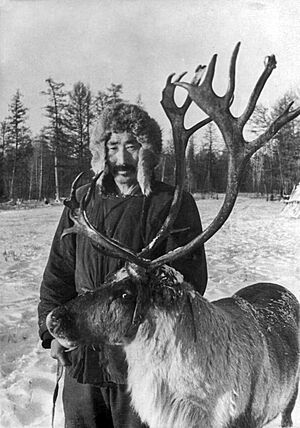

The people living in the vast forests (taiga) and cold northern lands (tundra) east of the Yenisei River and north of Lake Baikal were different. They show a strong connection from the Stone Age all the way to the Middle Ages. Even though the area is huge, there are only small differences between local groups, suggesting they moved around a lot.

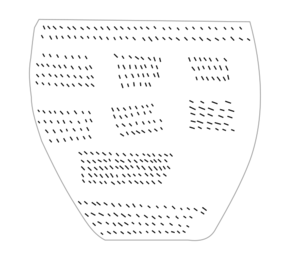

The first culture in Yakutia to make pottery was the Syalakh culture (around 5000 BC). They made pottery with net patterns. Their tools were made of flint and bone. These people were nomads who hunted and fished, staying at certain spots during different seasons.

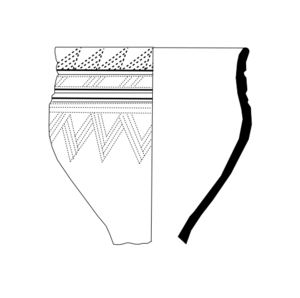

The Syalakh culture slowly changed into the Belkachi culture. Their pottery had cord decorations and zigzag lines. They buried their dead lying on their backs in earth graves.

The Ymyyakhtakh culture (2200–1300 BC) is known for its "waffle ceramic" pottery, which had a unique texture. Towards the end of this period, people in Yakutia started using bronze.

The Ust-Mil culture followed. Around 1000 BC, a unique culture developed on the Taymyr Peninsula, similar to the Ust-Mil culture. The Iron Age began in Yakutia around 500 BC. People started using iron tools and weapons, but their daily life didn't change much.

In the Baikal region, things were similar to Yakutia until the Late Bronze Age. People lived in multi-layered sites with hearths and pits, but no signs of permanent buildings. Their pottery was similar to Yakutia's. They buried their dead lying on their backs, often covered with stone slabs. They hunted bears, fish, elk, and beavers. Carvings on bones and rocks show how important hunting was to them. Unlike Yakutia, people in the Baikal region started herding animals before the Middle Ages, with the earliest evidence from the Copper Age Glazkov culture.

Settled Societies in West Siberia and Baikal

From the Neolithic or early Copper Age, settled groups appeared in southwest Siberia. Herding animals became a very important part of their economy. This new way of life slowly spread to the Baikal region.

Pottery Styles

Throughout Siberia's ancient history, from the Neolithic to the Iron Age, pottery styles were quite simple. Most pots were round with curved sides. Early pots had curved bases, but later ones had flat bases.

In western Siberia, pottery was often decorated with comb patterns, rows of dots, and dimples. As the Andronovo culture grew in the Middle Bronze Age, a new style spread. Their pots had zigzag lines and triangles. These styles continued into the Iron Age, though decorations became simpler.

Art and Small Finds

Besides pottery decorations, art in southern Siberia mostly appeared in the early Bronze Age.

The Karakol culture in Altai and the Okunev culture near the Yenisei River made human-like figures on stone slabs. The Okunev culture also made human-shaped sculptures. The art of the Samus culture near the Ob River was similar, with human figures and animal heads on pottery.

Later, in the Late Bronze Age, people made "deer stones." These were stone slabs carved with images of deer. These inspired the art of the later Scythian nomads.

In the early Iron Age, the horse nomads of southern Siberia developed a unique "animal style" art. This style influenced the cultures of the west Siberian lowlands. The Kulaika culture near the Ob River made bronze figures of animals and people, especially eagles and bears.

Ancient Homes

Wood was the main building material in ancient North Asia. Stone was mostly used for foundations. Most houses were partly dug into the ground, less than 1 meter deep. They were usually rectangular or circular. Roofs were likely made of wood. Many houses had a small porch at the entrance. Inside, there was usually one or more hearths (fireplaces).

People preferred to build settlements near rivers and lakes. Settlements could be small groups of houses, large open villages, or even fortified "city-like" places.

Small villages were common in all settled cultures. Some settlements, like Botai, grew very large. Larger settlements often had walls and graveyards outside the walls, like Sintashta and Tshitsha in western Siberia. These city-like settlements had houses packed closely together in a planned way. Fortified settlements on high ground, like those in the Minusinsk Hollow, were usually smaller. We're not sure what they were for – maybe temporary shelters, homes for leaders, or sacred places.

Society and Leaders

In the early Bronze Age, settled groups in West Siberia developed complex societies. This is shown by their city-like settlements and by differences in grave goods, which suggest some people were richer or more powerful than others. This social difference seemed to disappear in the Middle Bronze Age, but then reappeared in the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age.

Since ancient writers didn't know much about northern West Siberia, and the people there didn't write things down, it's hard to know many details about their society. However, Chinese writings about the Wusun people (who lived in the Tian Shan mountains) mention they had a king and nobles.

How They Lived (Economy)

The economy of settled people in ancient Siberia was mostly based on herding animals. They raised cattle, sheep, and goats. Raising horses became very important in western Siberia, especially in the Iron Age. The Xiongnu also raised pigs and dogs. Hunting and fishing were important at first, but became less so over time.

Many researchers think that agriculture (farming) was widely practiced, based on tools and possible irrigation systems. However, clear evidence like grain remains are mostly found in the southernmost cultures, like the Wusun and northern Xiongnu areas. There, people grew millet, and traces of wheat and rice have also been found. Millet seeds in graves in Tuva might mean there were settled farmers there who also worked with metal, living alongside the horse nomads.

From the Copper Age onwards, people also mined ores and worked with metals. We know this from finding slag (waste from metalworking), tools, and workshops.

Beliefs and Burials

Burial customs varied a lot among settled societies. In western Siberia during the Copper Age, people were buried in simple flat graves, lying on their backs. In the early Bronze Age, people started building kurgans (burial mounds). These were for important people, perhaps warriors, who were buried in wooden or stone structures, not just simple pits.

In the Middle Bronze Age, Andronovo kurgans were built, but the grave goods didn't show much difference in status. Bodies were buried in a crouching position or cremated. Later, the Karasuk culture near the Yenisei River built rectangular stone enclosures around tombs. The Tagar culture in the Iron Age developed these into stone-cornered kurgans. The early Iron Age Slab Grave culture in the Transbaikal area sometimes buried their dead in stone box-like graves.

Only a few special religious sites are known. The Afanasevo culture in southern Siberia had burnt offering places near their burial sites. These were simple stone circles with ashes, pottery, animal bones, and tools. Near the early Bronze Age settlement of Sintashta, there were circular buildings with wooden stakes and walls, likely used for religious ceremonies.

Iron Age Steppe Nomads

The horse nomads who lived on the Asian steppes for centuries are a more recent development. Even in the late 1000s BC, settled herders lived in these dry regions. The horse nomads replaced them in the first 1000 years BC, though we don't know exactly how.

The line between nomads and settled groups to the north was often blurry. People in the Minusinsk hollow remained settled herders in the Iron Age, but their culture was very similar to the nomads. The Xiongnu in the Transbaikal region had traits of both horse nomads and settled farmers. In northern Tian Shan, nomadic Sakas lived there first, but later the settled Wusun took over.

Archaeologists often call the early nomadic cultures "Scythian" (a Greek name for nomads north of the Black Sea). This term is used broadly for all horse nomads in the Eurasian steppe. After 200 AD, the "Hunnic-Sarmatian" period began, named after two nomadic groups. This lasted until the 500s AD.

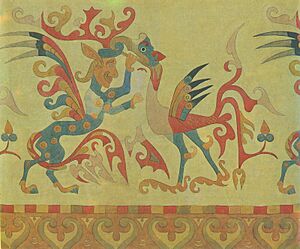

Nomad Art

While settled cultures in the Bronze Age often used human-like designs, the horse nomads developed the "Scytho-Sarmatian animal style." This art style was shared by all steppe people in Asia and Eastern Europe. It mostly featured wild animals, but strangely, not many horses or people, even though horses were central to their lives.

Common designs included deer (often lying down), elk, big cats (showing influence from the Near East), griffins, and hybrid creatures. Sometimes, animals were curled up together, or different animals were intertwined. Lines of the same animal often formed borders, and animal heads were used as decorations.

In the western steppes, metal objects were almost always decorated with animal style elements. In the frozen ground of southern Siberia and Transbaikal, felt carpets and other textiles with animal designs have been found. One amazing find is a felt swan stuffed with moss! Stone was used less often, mainly for "deer steles"—stone slabs decorated with deer, likely used as grave markers. Important people even had animal style tattoos on their bodies.

The exact origins of the animal style are unclear. Some think it was influenced by ancient Eastern art. But early finds in southern Siberia suggest it might have developed right there on the steppes. It's clear that Greek and Persian art later had a big impact on steppe art, especially in Central Asia.

Nomad Society

Horse nomad societies in the Bronze Age shared some features. They had powerful warrior leaders whose wealth was clear from their fancy grave goods. Chinese reports give us details about the Xiongnu society. They were divided into clan-like groups that formed large alliances. Their leaders had a strict hierarchy, all under the main commander, the Chanyu.

Nomad Economy

The horse nomads of Inner Asia were nomadic herders. They probably traveled in small groups. They focused on raising sheep, goats, and horses. In some areas, they also raised camels. Farming was done by settled people nearby, but it wasn't a big part of the nomads' economy. Mining and metalworking, known for some nomadic cultures, were probably done by settled groups too.

Nomad Religion and Burials

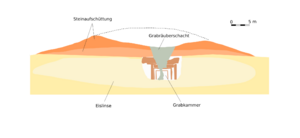

All horse nomad cultures buried their dead in large mounds called kurgans. These mounds varied greatly in size, from 2 to 50 meters wide and less than a meter to over 18 meters high. This likely showed differences in social status.

In some regions, kurgans were surrounded by stone enclosures. The Tagar culture had rectangular tombs sometimes surrounded by stones. In Tuva, some kurgans had rectangular or round stone walls. Kurgans themselves were built from earth and stone, depending on the region.

Under the kurgan, there was usually one or more tombs. The body was placed in a wooden chamber or a stone box. Wooden chambers were for higher-status people. In the Bronze Age, bodies were usually crouched, but in the Iron Age, they were laid on their backs.

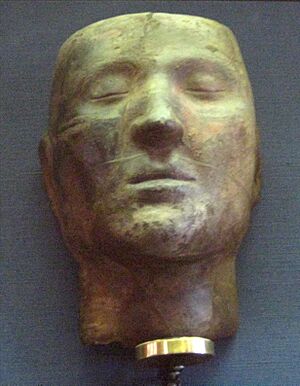

In Altai and Tuva, some bodies were preserved as "ice mummies" in the frozen ground. This allowed scientists to study them in detail. Before burial, their internal organs and muscles were removed, and the holes were stitched with tendons and horse hair. It's unclear if skull damage happened before or after death. Important bodies were also tattooed and embalmed. The Greek historian Herodotus described similar traditions for the Scythians.

Along with the body, burial chambers contained grave goods, which varied greatly in richness. Ordinary warriors were buried with a fully equipped horse and weapons. Women were buried with a horse, a knife, and a mirror. High-ranking people had much richer burials. These could include up to twenty-five richly dressed horses and a fancy chariot. The burial chamber itself was made of wooden planks. The body, often with a woman who might have died with him, lay dressed in a long wooden coffin. In Noin Ula in Mongolia, a woman's braids were buried instead of her body.

Famous kurgans include those at Pazyryk in Altai, Noin Ula in Mongolia, and Arzhan in Tuva. The frozen ground there preserved organic materials like felt carpets, decorated saddles, and clothing. Even though many large kurgans were robbed, some amazing finds remain, including countless gold objects.

Since there are no written records from these people, we learn about their religion from later groups and from the archaeological finds themselves. Their burial rituals clearly show they believed in an afterlife. They thought the dead needed the same things they had in life, which is why they were buried with their belongings.

|

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |