Prisoners of war in the American Revolutionary War facts for kids

During the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), how prisoners of war (POWs) were managed was very different from today. In modern times, rules like the Geneva Conventions say that captors must care for their prisoners. But in the 1700s, it was expected that a prisoner's own side, or their family, would provide their food and supplies.

Contents

American prisoners

King George III of Great Britain said American soldiers were traitors in 1775. This meant they were not treated as regular prisoners of war. However, the British hoped to make peace, so they didn't usually try or hang them. This was to avoid making the public feel more sympathy for the Americans.

Even without executions, many Americans died from neglect, starvation, and disease.

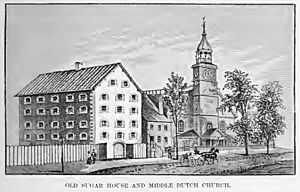

The British often kept American prisoners in large cities they controlled. These included New York City, Philadelphia, and Charleston, South Carolina. There wasn't much space or good facilities for so many prisoners. Sometimes, the number of soldiers held prisoner was even larger than the local population.

Some American prisoners were also held in St. Augustine, Florida.

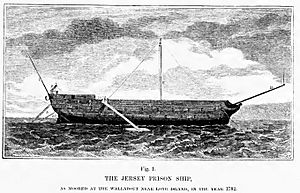

Prison ships

To deal with the large number of prisoners, the British used old or damaged ships as prisons. These "prison ships" had terrible conditions. Many more Americans died from neglect on these ships than were killed in battles.

The American army tried to send supplies, but it was very hard. For example, Elias Boudinot, a supply officer, had to compete for supplies needed by George Washington's army at Valley Forge. By the end of 1776, diseases and starvation had killed thousands of men captured in just two months.

At least 16 old ships, including the famous HMS Jersey, were used as prisons in Wallabout Bay near Brooklyn, New York. This was from about 1776 to 1783. Guards often treated prisoners badly. They would offer freedom if prisoners joined the British Navy, but few did. Over 10,000 American prisoners died from neglect on these ships. Their bodies were often thrown overboard or buried in shallow graves.

Over the years, many remains were found and later buried at the Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument in Fort Greene Park. This park was also part of the Battle of Long Island.

The American Revolution was very expensive. A lack of money and supplies led to the horrible conditions on British prison ships. The hot climate in the South made things even worse. The main cause of death was disease, not starvation. The British didn't even have enough good medical supplies for their own soldiers, let alone for prisoners.

Many prisoners in the North joined the British military to save their lives. Most American POWs who survived were held until late 1779. Then, they were exchanged for British prisoners. Very sick prisoners were sometimes moved to "hospital ships," but these were often just as bad as the prison ships.

Prison laborers and other prisoners of the British

American prisoners were also held in other parts of the British Empire. Over 100 prisoners were forced to work in coal mines in Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. They later joined the Royal Navy to get their freedom.

Other American prisoners were kept in England, Ireland, and Antigua. By late 1782, over 1,000 American prisoners were in England and Ireland. They were moved to France in 1783 before being released.

American soldiers captured at Cherry Valley were held by British supporters (Loyalists) at Fort Niagara and Fort Chambly in Canada.

British, Hessian, and Loyalist prisoners

American laws of war

During the American Revolution, George Washington and his Continental Army tried to follow rules for treating prisoners of war. This was different from how the British often treated American prisoners. Americans believed that all captives should be taken prisoner and treated well.

On September 14, 1775, Washington told his troops: "Should any American soldier be so base and infamous as to injure any [prisoner]... I do most earnestly enjoin you to bring him to such severe and exemplary punishment as the enormity of the crime may require."

After winning the Battle of Trenton in December 1776, Washington captured hundreds of Hessian soldiers. He ordered his troops to treat them "with humanity." He said, "Let them have no reason to complain of our copying the brutal example of the British army." The official American policy was to show mercy to enemy troops.

Grievances

While British and Hessian prisoners generally had better conditions than Americans, there were still cases of cruelty. Some states treated prisoners very badly. Prisoners often complained about bad food, dirty conditions, and physical abuse. The treatment of prisoners varied from state to state. Supplies for prisoners were often poor, especially in the later years of the war.

British and German prisoners

The British and Germans had similar experiences as POWs. The Continental Congress had the same rules for all enemy soldiers. However, British troops were seen as more important than the German mercenaries. So, there were more examples of British prisoners being exchanged.

Americans grew to dislike the British more than the Germans, who were generally better behaved. British prisoners were more likely to cause trouble and fight with guards. This was because they felt more strongly about defeating the Americans than the Germans did.

Loyalists

Loyalists were American colonists who supported the British. They were the most disliked prisoners. The Continental Congress said that prisoners of war were soldiers, not criminals. But depending on the state, Loyalists were often treated more like criminals than POWs. There was a big debate about whether to treat Loyalists as enemy soldiers or as citizens who had committed treason.

Prison towns

There were very few federal prisons in America. The Thirteen Colonies and the Continental Congress couldn't easily build new ones for British and German soldiers. Instead, Congress sent most British and Hessian prisoners to local American towns. Local officials were told to hold them under strict rules.

The Continental Congress decided where prisoners went, and towns often had little warning or say in the matter. Prison towns had the difficult job of providing for hundreds or thousands of prisoners. If a town couldn't afford to feed them, prisoners were put to work to feed themselves. British and German prisoners worked in gardens, on farms, and for craftsmen. They also did other simple jobs. Towns tried to make the prisoners useful and often helped them find work.

The more useful the prisoners were, the less money the town had to spend on them. If a town couldn't build barracks for prisoners, they were housed in churches or even in citizens' homes. This forcing of Americans to house prisoners was a big source of anger.

Even when prisoners weren't in private homes, they were often in public view. This caused fear, anger, and resentment. Prisoners were usually not locked up all day. They could be out in public. Security was a problem for prison towns. There was no official police force, and the army was busy fighting. So, local militias and volunteers usually guarded the prisoners. Protests in prison towns were common. People who refused to house prisoners were fined, jailed, or even had their property taken away.

How prisoners were received varied by location. Prisoners in Boston generally found the people to be polite and accepting. In Virginia and other southern states, wealthy plantation owners were happy to have prisoners. They could use them for free or cheap labor.

However, poorer people in the South were less accepting of large prisoner populations. In Maryland, the state militia even challenged the Continental Army when it tried to bring prisoners into the state. The South had a general fear of uprisings because of the enslaved population.

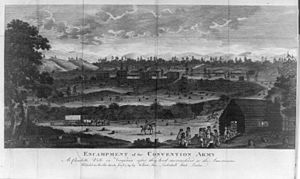

Convention Army

On October 17, 1777, nearly 6,000 British and Hessian soldiers of the Convention Army surrendered to the Americans. This meant the Continental Congress now had a huge number of prisoners on American soil. It was already struggling to provide for its own army. After this surrender, it also had to provide for enemy soldiers.

Background

After the British, German, and Canadian troops were defeated, General Burgoyne and General Gates couldn't agree on what to do with the 5,900 prisoners. The agreement, called the Convention of Saratoga, said the troops would return to Europe and never fight in North America again. Congress thought this was a bad part of the treaty, especially after such a big victory. So, they kept delaying its approval.

General Burgoyne became frustrated and openly criticized Congress. Congress used his words as proof that he planned to break the agreement. They then suspended the agreement until Great Britain recognized American independence. As a result, the Americans held the Convention Army for the rest of the war.

Marches

The Convention Army was marched across the colonies during the war. First, they stayed in Massachusetts for a year. In 1778, they were moved to Virginia for two years. In 1780, they were moved north again and split up into different states and towns. The marches themselves were very hard on the soldiers. But their lives usually got better once they reached their destinations. The main reasons for these marches were security and money.

When resources became scarce in Massachusetts, Congress ordered the army to move South. The war was different in the North compared to the South. By 1780, it was hard to feed the British and German prisoners and their guards in the South. Their presence also became a security risk because the British had started their main campaigns in the South. This raised fears of uprisings. So, the Convention Army was ordered to march back North and was divided up.

Freedom

There were three ways for a prisoner of war to gain freedom: desertion, exchange, or parole. Usually, a small group of hired militia guards watched over captured British and German soldiers. It was hard for these guards to watch prisoners effectively.

The Convention Army first accepted being POWs because they thought they would be sent home within a year. When it became clear that Americans wouldn't let them return until the war ended, tensions grew. Desertions (escaping) increased quickly. Both Americans and high-ranking British officers tried to stop troops from deserting, but it mostly failed. Many prisoners who escaped stayed in America, often marrying American women and starting families. A large number of Hessians remained in the US after the war for this reason. Between the Siege of Yorktown (1781) and the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1783), many Convention troops, mostly Germans, escaped and settled in the United States. The American government couldn't stop them.

The other two official ways to gain freedom, parole and exchange, were common for high-ranking officers. Parole meant an individual prisoner was released from prison or house arrest under a promise not to fight again. This process was simple and fast. Most British and German prisoners tried to get parole. However, breaking parole was common, as it made desertion easier. Some British and Hessian prisoners were paroled to American farmers. Their labor helped with the shortage of workers because many American men were serving in the Continental Army.

Exchange was a very complex and slow process. It involved talks and agreements between a new, inexperienced nation and a country (Britain) that refused to recognize American independence. A major problem for exchanges was that the British didn't want to treat Americans as regular soldiers, only as rebels. This prevented many exchanges. By March 1777, Congress and the states had agreed on the idea and process of exchanges. Congress handled exchanges, while states and local governments had more power over parole.

Reaction and impact

The capture of thousands of British prisoners by the Americans had an important effect. It made British officials less likely to hang American colonial prisoners. They feared that Americans would do the same to British prisoners. After the Convention Army was captured, the number of prisoner exchanges increased a lot.

In the early years of the war, the Continental Congress tried to give prisoners of war the same amount of supplies as their own guards. But after the Convention Army was captured, resources became scarce. The federal government had to rely on state governments to provide for prisoners. From 1777 to 1778, General Clinton provided food for the Convention Army. But he eventually stopped, putting the full cost on the US government. To make up for the lack of resources, British and German prisoners were moved from state to state. These marches were largely due to dwindling supplies.

Besides the official marches of the Convention Army, captured prisoners were sometimes paraded through cities after American victories. This was a way to celebrate for Americans and humiliate their enemies. The parades aimed to boost morale among Americans. The Revolutionary War had a terrible impact on communities. Seeing clear examples of American progress and victory helped gain support for the war effort.

Notable prisoners of war

- Robert Brown, U.S. Congressman

- Philip Freneau, poet

- Charles Lee, major general

- George Mathews, brigadier general, U.S. Congressman, governor of Georgia

- John Sullivan, major general

- William Alexander, Lord Stirling, brigadier general

- Samuel Miles (Philadelphia Mayor, later first faithless elector - Presidential election 1796)

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |