Remington Kellogg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

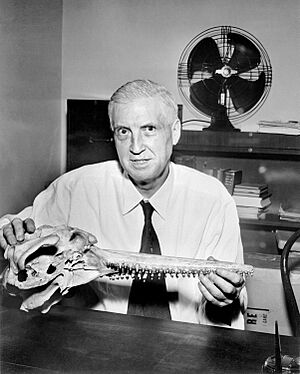

Remington Kellogg

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 5 October 1892 |

| Died | 8 May 1969 (aged 76) |

| Occupation | Zoologist |

| Spouse(s) | Marguerite Henrich |

Remington Kellogg (born October 5, 1892 – died May 8, 1969) was an American scientist who studied animals. He was also a director at the United States National Museum. His main work was about marine mammals, which are mammals that live in the ocean, like whales and dolphins.

Contents

Becoming a Naturalist

Remington Kellogg was born in Davenport, Iowa. From a young age, he loved studying wildlife. He spent his free time building a collection of stuffed birds and mammals. By the time he was ready for college, he knew he wanted to be a naturalist, someone who studies nature.

He chose the University of Kansas because it had courses in his favorite subjects. He first studied entomology (the study of insects), but later switched to studying mammals. From 1913 to 1916, he worked with Charles D. Bunker, who was in charge of the bird and mammal collections at the university's museum. Kellogg wrote his first scientific paper because of this work. He earned his first degree in 1915 and his master's degree the next year.

Starting His Career

After college, Kellogg immediately started working for the United States Bureau of Biological Survey in Kansas and North Dakota. This government agency studies and protects wildlife. In late 1915, the Survey sent him to Washington, D.C.. From there, he visited museums in the eastern states.

Around this time, he decided to focus on marine mammals. In 1916, he began studying for his Ph.D. (a high-level degree) in zoology at the University of California at Berkeley. He was given a special teaching job by John C. Merriam. Kellogg studied fossils of pinnipeds, which are marine mammals like seals and walruses. He wrote his first important papers on this topic in 1920 and 1921.

Serving in World War I

Kellogg served in the Army in France during World War I. Even while serving, he found time to collect animal specimens. He sent these back to Berkeley and the University of Kansas. He finished his military service in July 1919. Then, he returned to Berkeley to finish his Ph.D. He changed his focus from zoology to studying vertebrate paleontology (the study of fossil animals with backbones) under John C. Merriam.

Working at the Smithsonian

In 1921, Kellogg became an assistant biologist for the Biological Survey in Washington. For the next eight years, he mostly studied toads and what hawks and owls ate. He also studied alligators to see if they were dangerous predators. This helped solve arguments about hunting them.

John C. Merriam encouraged Kellogg to use his free time to study fossil marine mammals. He explored the Calvert Cliffs in Maryland. He added many new fossils to the museum's collections. His experiences there became the basis for his Ph.D. paper. It was called The History of Whales - Their Adaptation to Life in the Water. In this paper, he studied how whale bodies changed to live in water.

In 1928, Kellogg became an assistant curator at the United States National Museum. A curator is someone who manages a museum's collections. In 1941, he became the main curator. At the museum, he spent time studying ancient whales called Archaeoceti from the Eocene and early Oligocene periods. He also studied Miocene Cetacea (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) from North America.

In 1948, he was made director of the Museum. In 1958, he became an assistant secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was recognized for his important work. He was chosen to be a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1951. Later, he joined the American Philosophical Society in 1955 and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1960.

Protecting Whales

Kellogg's Ph.D. paper made him an expert on cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises). People were becoming worried about too much whaling. Whales were being hunted so much that their numbers were dropping. Because of his expertise, Kellogg was asked to speak at a conference about whaling in 1930. This meeting was organized by the League of Nations, an organization that worked for world peace.

More conferences followed. Kellogg was chosen to represent the U.S. at the International Conference on Whaling in London in 1937. This meeting led to the first rules to protect whales, called the International Agreement for the Regulation of Whaling.

Kellogg led the U.S. team in two more conferences in 1944 and 1945. He was also the chairman of the 1946 conference. After that, he became the U.S. commissioner for the International Whaling Commission (IWC) from 1949 to 1967. The IWC is an international group that manages whaling and whale conservation. He was the vice-chairman of the Commission from 1949 to 1951 and chairman from 1952 to 1954.

Later Years and Legacy

Remington Kellogg retired from his jobs at the Smithsonian in 1962. However, he continued to work on his studies of Miocene Cetacea. He published nine more papers about fossil marine mammals between 1965 and 1969. Due to his health and slow progress, he had to stop his work with the International Whaling Commission after 1964.

He passed away from a heart attack at his home in Washington on May 8, 1969. He was recovering from a broken hip at the time. Remington Kellogg is remembered for his important contributions to understanding marine mammals and for his efforts to protect whales.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |