Robert Russa Moton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Russa Moton

|

|

|---|---|

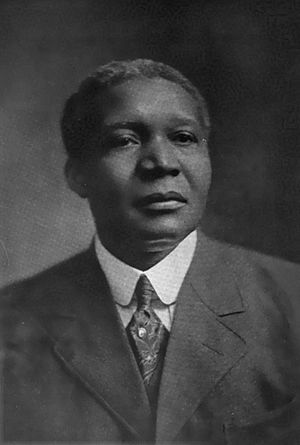

Robert Moton in 1916

|

|

| Born | August 26, 1867 |

| Died | May 31, 1940 (aged 72) |

| Education | Hampton Institute, Tuskegee Institute |

| Organization | Fellowship of Reconciliation, Congress of Racial Equality, War Resisters League, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Social Democrats, USA (National Chairman), A. Philip Randolph Institute (President), Committee on the Present Danger |

| Movement | Civil Rights Movement, Peace Movement, Socialism |

| Awards | Spingarn Medal from the NAACP |

Robert Russa Moton (born August 26, 1867 – died May 31, 1940) was an important American educator and author. He worked as an administrator at Hampton Institute. In 1915, he became the leader of Tuskegee Institute after its founder, Booker T. Washington, passed away. Moton held this important job for 20 years until he retired in 1935.

Contents

Robert Russa Moton's Early Life and Education

Robert Russa Moton was born in Amelia County, Virginia, on August 26, 1867. He grew up nearby in Rice, Prince Edward County, Virginia. His family had come to the Americas from Africa.

Moton was a dedicated student. He graduated from the Hampton Institute in 1890.

Family Life

In 1905, Robert Moton married Elizabeth Hunt Harris. Sadly, she passed away in 1906. He then married his second wife, Jennie Dee Booth, in 1908. They had three daughters together:

- Charlotte Moton (Hubbard)

- Catherine Moton (Patterson)

- Jennie Moton (Taylor)

All three of his daughters grew up, married, and had their own families.

Leading the Way in Education

In 1891, Moton was chosen to be the commandant of the male student cadet corps at Hampton Institute. This role was similar to being the Dean of Men. He served in this position for over ten years and was often called "Major."

Becoming Principal of Tuskegee Institute

In 1915, after the death of Booker T. Washington, Robert Moton became the second principal of the Tuskegee Institute. He continued the school's work-study program, which combined learning with practical work.

Moton also made many improvements to the school:

- He focused more on education, adding liberal arts subjects to the curriculum.

- He started bachelor of science degrees in agriculture and education.

- He made the courses better, especially for training teachers.

- He hired more skilled teachers and administrators.

- He built new buildings and facilities.

- He greatly increased the school's money by keeping strong connections with wealthy white supporters in the North.

Helping Soldiers During World War I

During World War I, President Woodrow Wilson asked Moton to travel to Europe. His job was to check on the conditions of African-American soldiers. He often saw that these soldiers were treated unfairly. Moton challenged these unfair practices. He encouraged black soldiers to speak out against segregation when they returned to the United States.

Moton also wrote several books while he was principal. In 1919, he attended the First Pan-African Congress in Paris. There, he met other educators and activists from around the world.

Speaking at the Lincoln Memorial

In 1922, Moton was the main speaker at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. However, he was not allowed to sit with the other speakers. This showed the unfair treatment that was still common at the time.

His Approach to Race Relations

In dealing with race relations, Moton believed in "accommodation" rather than direct confrontation. He thought that the best way for African Americans to make progress was to show white people their worth through excellent behavior. He did not directly fight against segregation or challenge white authority.

Moton was a member of the boards of major organizations that gave money to good causes. He worked with important people like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller Jr.. His influence was very strong. For example, when Julius Rosenwald, the president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, gave money to build over 6,000 "Rosenwald" schools for rural Southern African Americans, Moton's quiet work behind the scenes helped make it happen.

The Great Mississippi Flood and Politics

In 1927, the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 caused huge damage. Thousands of people, mostly African Americans, were stuck on the Greenville, Mississippi levee. They desperately needed food, clean water, and shelter. Instead of being evacuated, many African Americans were held on the levee and forced to work.

To avoid a scandal, future President Herbert Hoover asked Robert Moton for help. Hoover formed the Colored Advisory Commission, led by Moton, to investigate the problems in the flood area. The commission found terrible conditions. Moton told Hoover about these findings and asked for immediate help for the flood victims.

However, this information was never made public. Hoover had asked Moton to keep the investigation quiet. In return, Hoover suggested that if he became president, Moton and other black leaders would have an important role in his government. Hoover also hinted that he would divide land from struggling farms into small farms owned by African Americans.

Because of Hoover's promises, Moton made sure the commission did not reveal the full extent of the abuses. Moton also encouraged African Americans to support Hoover for president. But after Hoover was elected president in 1928, he did not keep his promises to Robert Moton or the black community. Because of this, Moton stopped supporting Hoover in the 1932 election and joined the Democratic Party.

Moton was a member of the Phi Beta Sigma fraternity, along with George Washington Carver.

Later Life and Legacy

Robert Moton retired from Tuskegee in 1935. He passed away at his home, Holly Knoll, in Gloucester County, Virginia, in 1940 at the age of 72. He was buried at the Hampton Institute. Tuskegee Institute named the field where Airmen trained during World War I after Robert Moton, honoring his contributions to the school.

Honors and Recognition

- Moton Field, the first training base for the famous Tuskegee Airmen during World War II, was named after him. Moton had died the year before the Army officially started training African-American military pilots at Tuskegee. But under his leadership, the school had already started aeronautical training with facilities and instructors. These resources helped Tuskegee Institute become part of the Civilian Pilot Training Program, which led to the training of African-American pilots.

- His retirement home, Holly Knoll in Gloucester County, is now known as the Robert R. Moton House. It was recognized as a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1981.

- The former R. R. Moton High School in Farmville, Prince Edward County, was named a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1998. It is now the Robert Russa Moton Museum, which studies civil rights in education.

- Robert R. Moton High School in Leeds, Alabama, which operated from 1948 to 1970, was also named in his honor.

- Several elementary schools across the country are named after him, including in Hampton, VA, Brooksville, FL, Miami, FL, Westminster, MD, Easton, MD, Emporia, VA, and New Orleans, LA.

- In 1932, Moton received the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP.

- Moton Hall, a men's dormitory built in the late 1950s at Hampton University, is named for him.

Public Service Roles

Robert Moton played many important roles in public service:

- In 1918, he traveled to France at the request of President Woodrow Wilson. His mission was to inspect U.S. black troops stationed there.

- In 1923, he helped create the Veterans Administration Hospital for Negroes in Tuskegee, Alabama.

- In 1927, he was the Chairman of the American National Red Cross's Colored Advisory Commission on the Great Mississippi Flood.

- In 1932, he served as the Chairman of the U.S. Commission on Education in Haiti.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |