Sebastian Haffner facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sebastian Haffner

|

|

|---|---|

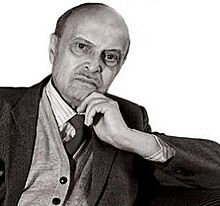

Haffner on book cover Germany: Jekyll & Hyde

|

|

| Born | Raimund Pretzel 27 December 1907 Berlin, German Empire |

| Died | 2 January 1999 (aged 91) Berlin, Germany |

| Occupation | Journalist and historian |

| Subject | Prussia, Otto von Bismarck, World War I, Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler, World War II |

| Children | Oliver Pretzel; Sarah Haffner |

Raimund Pretzel (born December 27, 1907 – died January 2, 1999) was a German journalist and historian. He was better known by his pen name, Sebastian Haffner. During World War II, he lived in Britain. Haffner believed that it was impossible to make peace with Adolf Hitler or with the German Reich (Empire). He thought peace could only happen if Germany went back to being smaller states, like it was before 1866.

As a journalist in West Germany, Haffner liked to make his points very strongly. This sometimes caused him to disagree with his editors. He became more famous after he spoke out during the Spiegel affair in 1962. He also wrote for the student New Left movement, which was against fascism.

After leaving Stern magazine in 1975, Haffner wrote many popular books. These books focused on what he saw as important patterns in the history of the German Reich (1871–1945). His book Defying Hitler: A Memoir, published after he died, made him popular with new readers.

Contents

Early life and education

Growing up in Berlin schools

Sebastian Haffner was born Raimund Pretzel in Berlin in 1907. During World War I (1914–1918), he went to a primary school where his father was the principal. He remembered the war news like a sports fan following game scores. Haffner thought this idea of war as an exciting "game" made Nazism appealing to many young people. He felt it made Nazism seem simple and full of action, but also intolerant and cruel.

After the war, Haffner went to a grammar school in Berlin. There, he became friends with children from important Jewish families. These friends were smart, cultured, and had left-leaning political ideas. In 1924, he moved to another school, the Schillergymnasium in Lichterfelde. This school had many students from military families, and his political views became more conservative. Haffner later said that his experiences at these two schools shaped his whole life.

Witnessing Hitler's rise and leaving Germany

After January 1933, Haffner was a law student. He saw the SA (Nazi stormtroopers) act as "police." After the Reichstag fire in March, they chased Jewish and democratic lawyers out of the courts. What shocked him most was that no one seemed brave enough to resist. He felt that many people simply gave up when Hitler came to power.

Haffner went to Paris for his doctoral research to escape the situation. But he couldn't find work there, so he returned to Berlin in 1934. He had already written some short stories for the Vossische Zeitung. This helped him earn a living writing for style magazines, where the Nazis allowed some cultural freedom. However, political control became stricter. Also, his journalist girlfriend was pregnant and was considered Jewish under the Nuremberg Laws. This made them decide to leave Germany.

In 1938, Erika Schmidt-Landry (born Hirsch) went to England. Haffner followed her with a job from the Ullstein Press. They got married just weeks before their son, Oliver Pretzel, was born.

Britain's declaration of war against Germany in September 1939 saved Haffner from being sent back to Germany. As "enemy aliens," Haffner and his wife were held in camps. But in August 1940, they were among the first to be released from camps on the Isle of Man. In June, George Orwell's publisher, Fredric Warburg, released Haffner's first English book, Germany, Jekyll and Hyde. To protect his family in Germany, Haffner used his new pen name: Sebastian (from Johann Sebastian Bach) and Haffner (from Mozart's Haffner Symphony). In the House of Commons, people asked why such an important author was being held. Lord Vansittart called Haffner's book the most important analysis of "Hitlerism and the German problem."

Haffner as a political émigré

Understanding Germany: Jekyll and Hyde

In his book, Haffner argued that Britain was wrong to think its fight was only with Hitler, not with the German people. He said Hitler had gained many followers in Germany through normal ways. This didn't mean "Hitler is Germany," but it was wrong to think Germans were secretly against him.

Germans were divided when the war started. Less than one in five were "real Nazis." These "real Nazis" would never accept a peaceful Europe. Their anti-Semitism (hatred of Jewish people) was a way to find people who would persecute and murder others without question. These people would then be loyal to Hitler through "common crime."

Many Germans, perhaps four out of ten, wanted Hitler and the Nazis gone. But they were disorganized and felt hopeless. Many others, about the same number, feared another harsh peace treaty like the Treaty of Versailles. So, they accepted Hitler's rule as a "patriotic sacrifice." Haffner warned that if the Allies didn't make a big change, Germany's desire for power would just return.

Haffner strongly believed that the German Reich (Empire) had to disappear. He felt that the last 75 years of German history needed to be "erased." Germans should go back to 1866, when Prussia gained power over smaller German states. He argued that "No peace is conceivable with the Prussian Reich... whose last logical expression is no other than Nazi Germany." Haffner thought Germany should return to being smaller regional states, connected by European agreements, not just national ones.

He also said that if Germans became Bavarians or Saxons again, they might escape punishment from the Allies. He reasoned that "We cannot both get rid of the German Reich and... punish them for its sins." If the Allies wanted the "Reich mentality" to die, the new states needed a fair chance.

Haffner's view of Churchill

There's a story that Winston Churchill made his war cabinet read Haffner's book. Haffner admired Churchill too. He said his short biography, Winston Churchill (1967), was his favorite of his own books. When Churchill died in 1965, Haffner wrote that it felt like "English history itself" was being buried.

However, Haffner was disappointed that Churchill didn't support his ideas for a German Freedom Legion or a German committee in exile. Churchill used anti-Nazi Germans as advisors, but there was no group like the "National Committee for a Free Germany" in Moscow. Still, some believe that Churchill's ideas about post-war Germany might have come from Haffner's book.

Post-war journalism and German politics

Germany's division and Haffner's views

In 1941, David Astor invited Haffner to join The Observer newspaper. Edward Hulton also hired him to write for Picture Post. Haffner became a British citizen in 1948. He met other left-leaning journalists and exiles, like George Orwell, in a group called the Shanghai Club.

When David Astor returned from war service, he became more involved in The Observer. Haffner and Astor often disagreed. After a trip to the United States during the McCarthy era, Haffner became critical of the North Atlantic alliance. He also thought the 1952 Stalin Note, which offered Soviet withdrawal for German neutrality, should be taken seriously. In 1954, he moved to Berlin to be The Observer's German correspondent.

In Germany, Haffner also wrote for the conservative newspaper Die Welt. The publisher, Axel Springer, allowed discussions about Germany becoming neutral, like Austria. This idea was not fully dismissed until the Berlin Wall was built in 1961. Haffner joined Springer in criticizing the weak Western response to the wall. This led to his final break with Astor and The Observer.

Haffner was not against having a second German state. In 1960, he thought the GDR (East Germany) could become a "Prussian Free State." After the wall was built, Haffner believed there was no choice but to officially recognize East Germany. From 1969, he supported the Ostpolitik (Eastern Policy) of the new Social-Democratic Chancellor, Willy Brandt. This policy aimed to improve relations with Eastern Bloc countries.

The Spiegel affair and press freedom

On October 26, 1962, police raided the offices of Der Spiegel magazine in Hamburg. The publisher, Rudolf Augstein, and other editors were arrested. Defence minister Franz Josef Strauss accused them of treason. This was because of an article that talked about NATO's prediction of "chaos" if the Soviets attacked with nuclear weapons. The article also criticized the government's lack of preparation. Strauss later had to admit he didn't start the police action.

Axel Springer offered his printing presses to Der Spiegel so they could keep publishing. Haffner, writing in the Süddeutsche Zeitung, spoke out against the attack on press freedom. He mentioned the collapse of German democracy in 1933 and warned that democracy was at risk again. This event was a turning point for West Germany, moving away from an old authoritarian style. Haffner gained many new, more liberal readers through this.

Student protests and anti-Springer campaigns

Haffner believed that West Germany hadn't fully dealt with its Nazi past. In Stern magazine, he called a police riot in West Berlin a "systematic, cold-blooded, planned pogrom." During this riot, a student protester named Benno Ohnesorg was killed.

On June 2, 1967, students protested against the visit of the Shah of Iran. Iranian counter-protesters, including agents from the Shah's intelligence service, attacked the students. The police joined in, beating students. An officer then shot and killed Benno Ohnesorg. Haffner wrote that "fascism in West Berlin had thrown off its mask" after this event.

Many people, including Haffner's daughter Sarah, became angry at his former employer, Axel Springer. After the socialist student leader Rudi Dutschke was shot in April 1968, Springer's newspapers were accused of encouraging violence. The Morgenpost even compared a protest blockade of its presses to Kristallnacht, when Jewish property was destroyed.

Ulrike Meinhof and terrorism

Haffner's strong opinions were not popular with Willy Brandt's Social Democrats or with Stern magazine. This was especially true after Ulrike Meinhof took more extreme actions. She believed that "Protest is when I say I don’t like this. Resistance is when I put an end to what I don’t like.” On May 19, 1972, the Red Army Faction (also known as the "Baader Meinhof Gang") bombed Springer's headquarters, hurting 17 people.

Haffner, like other writers, criticized Springer's journalism for planting "the seeds of violence." However, Haffner was also worried that many people on the left might help a fugitive like Ulrike Meinhof. He warned that romanticizing terrorism would hurt the left and its goals for reform.

Celebrating new liberalism in West Germany

Haffner disagreed with some strict security measures of the Brandt government. He opposed the 1972 Radikalenerlass (Anti-Radical Decree). This rule banned people with "extreme" political views from certain public jobs. Haffner argued that Marxists should be able to be teachers, not because they were liberals, but because "we are liberals."

However, Haffner stopped using strong words like "police pogroms." He said that while police might have beaten protesters in the 1960s, no one ever heard of them torturing anyone.

West Germany had changed a lot. Haffner felt it had moved away from its past faster than anyone expected. The old authoritarian way of thinking was "passé" (outdated). The atmosphere became "more liberal, more tolerant." He saw a modest, global-minded public emerging from a nationalistic and militaristic past.

Controversy over Franco's Spain

In October 1975, Stern magazine refused to publish an article by Haffner. They said it went against the magazine's commitment to democracy.

Just two months before Franco's death, Spain executed five people for killing policemen. Haffner refused to join the international criticism. In an article called "Hands off Spain," he seemed to defend Franco's dictatorship. He argued that Spain had done well under Franco for 36 years. He said there was economic progress, even without political freedom.

Many people felt Haffner had gone too far with his provocative style. His readership was reportedly falling. Haffner admitted he might have been moving to the right while Stern was moving to the left. In his last Stern article, he said he didn't regret supporting Brandt's Ostpolitik. But he felt some disappointment. He thought the easing of Cold War tensions hadn't brought much good, and West Germany itself had seen better times.

Haffner's historical writings

At 68, Haffner decided to focus on writing popular books about German history. Some of his articles in Stern had already become bestsellers. His book Die verratene Revolution (1968), which criticized Social Democrats in 1918, had 13 editions. Like all his work, it had no footnotes and was written for a general audience. His book Anmerkungen zu Hitler (1978), published in English as The Meaning of Hitler, sold a million copies. Golo Mann called it a "witty, original and clarifying book... excellently suited for discussion in the upper classes of schools."

Haffner agreed that Hitler was not truly Prussian. Prussia was a "state based on law" and was tolerant. But Haffner's main idea, summarized in his last book Von Bismarck zu Hitler (1987), remained. He believed that the German Empire, created by Prussia, continued with the same goal: to be a great power or collapse. Because of this history, Haffner was sure that Germany's neighbors would never allow a new, large German power bloc to rise again.

Later life and family

In 1989-1990, when the Berlin Wall fell, Haffner reportedly worried that Germans had not learned enough from the traumas of 1945. He feared they might again become overly nationalistic. According to his daughter Sarah, the peaceful unification of Germany pleased him. But it also made him feel that he had lived past his time. Haffner died on January 2, 1999, at age 91.

His wife, Christa Rotzoll, a journalist he married in 1969, died before him in 1995. Haffner was survived by his two children with Erika Schmidt-Landry. Sarah Haffner (1940–2018) was a painter and filmmaker. She believed her own political involvement might have influenced her father's interest in the student movement in the 1960s. His son, Oliver Pretzel (born 1938), was a Professor of Mathematics. After his father's death, Oliver put together a memoir his father started in 1939. This memoir was published as Geschichte eines Deutschen/Defying Hitler.

Marcel Reich-Ranicki's memories

Haffner's close friend, the literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki, said that Haffner's books were as informative and entertaining as his conversations. Reich-Ranicki suggested that German journalists who lived in exile in England or the United States wrote differently. Even after returning, they wrote in a "clearer, more spirited" style that was both factual and witty. They found this combination was "also possible in German."

Selected works

In English and English translation

- 1940 Germany: Jekyll & Hyde, Secker and Warburg, London. 2008, Germany, Jekyll & Hyde: A Contemporary Account of Nazi Germany. London: Abacus.

- 1941 Offensive Against Germany, London: Searchlight Books/Secker & Warburg.

- 1979 The Meaning of Hitler [Anmerkungen zu Hitler]. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN: 0-674-55775-1.

- 1986 Failure of a Revolution: Germany 1918-1919 [Die verratene Revolution – Deutschland 1918/19], Banner Press, ISBN: 978-0-916650-23-0

- 1991 The Ailing Empire: Germany from Bismarck to Hitler [Von Bismarck zu Hitler: Ein Rückblick], New York: Fromm International Publishing, ISBN: 978-0-88064-127-2

- 1998 The Rise and Fall of Prussia [Preußen ohne Legende], Phoenix Giants, ISBN: 978-0-7538-0143-7

- 2003 Defying Hitler, a Memoir, [Geschichte eines Deutschen. Die Erinnerungen 1914–1933], London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN: 0-312-42113-3.

In German

- 1964 Die sieben Todsünden des deutschen Reiches im Ersten Weltkrieg. Nannen Press, Hamburg.

- 1967 Winston Churchill, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg. ISBN: 3-463-40413-3

- 1968 Die verratene Revolution – Deutschland 1918/19, Stern-Buch, Hamburg. 2006, 13th edition: Die deutsche Revolution – 1918/19. Anaconda Verlag, 2008, ISBN: 3-86647-268-4

- 1978 Anmerkungen zu Hitler, Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main. ISBN: 3-596-23489-1. The Meaning of Hitler, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1979). ISBN: 0-674-55775-1. Published in English:

- 1979 Preußen ohne Legende, Gruner & Jahr, Hamburg. 1980 The Rise and Fall of Prussia, George Weidenfeld, London.

- 1980 Überlegungen eines Wechselwählers, Kindler GmbH, München. ISBN: 3-463-00780-0

- 1982 Sebastian Haffner zur Zeitgeschichte. Kindler, Munich. ISBN: 978-3463008394

- 1985 Im Schatten der Geschichte: Historisch-politische Variationen,. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart. ISBN: 3-421-06253-6

- 1987 Von Bismarck zu Hitler: Ein Rückblick, Kindler, Munich. ISBN: 3-463-40003-0.

- 1989 Der Teufelspakt: die deutsch-russischen Beziehungen vom Ersten zum Zweiten Weltkrieg. Manesse Verlag, Zurich. ISBN: 3-7175-8121-X

- 1997 Zwischen den Kriegen. Essays zur Zeitgeschichte, Verlag 1900.ISBN: 3-930278-05-7.

Published posthumously

- 2000 Geschichte eines Deutschen. Die Erinnerungen 1914–1933. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich. ISBN: 3-423-30848-6.

- 2000 Der Neue Krieg, Alexander, Berlin. ISBN: 3-89581-049-5

- 2002 Die Deutsche Frage: 1950 – 1961: Von der Wiederbewaffnung bis zum Mauerbau, Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt a. M.. ISBN: 3-596-15536-3

- 2003 Schreiben für die Freiheit, 1942-1949. Als Journalist im Sturm der Ereignisse. Frankfurt-am-Main.

- 2004 Das Leben der Fußgänger. Feuilletons 1933–1938, Hanser, Carl GmbH & Co., Munich. ISBN: 3-4462-0490-3

- 2016 Der Selbstmord des Deutschen Reichs, Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main. ISBN: 3-596-31002-4

- 2019 The Ailing Empire: Germany from Bismarck to Hitler, Fromm International Publishing, ISBN: 978-0-88064-127-2

See also

In Spanish: Sebastian Haffner para niños

In Spanish: Sebastian Haffner para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |