Sempringham Priory facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sempringham Priory |

|

|---|---|

Sempringham Parish Church

|

|

| General information | |

| Location | Sempringham, Lincolnshire |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 52°52′42″N 0°21′27″W / 52.878333°N 0.3575°W |

| Completed | 1140s |

Sempringham Priory was a special kind of religious building called a priory in Lincolnshire, England. It was located in a small medieval village called Sempringham, near Pointon. Today, you can't see the priory above ground. Only aerial photos show faint outlines of where its walls once stood. However, the old parish church of St Andrew's, built around 1100 AD, still stands alone in a field, showing where the priory used to be.

The priory was built by Gilbert of Sempringham. He was the only English saint to start his own monastic order, which is a group of people living together under religious rules. Sempringham Priory became an important place for religious pilgrimage when St Gilbert founded the Gilbertine Order in 1131. He started by teaching "seven maidens" who were his students. Alexander, who was the Bishop of Lincoln, helped set up the religious buildings north of St Andrew's Church as a protected area.

St Gilbert died at Sempringham in 1189 and was buried in the priory church. He was made a saint, or canonised, on October 13, 1202. This happened because many miracles were reported at his tomb in the priory. Because of him, the priory is sometimes called "St Gilbert Sempringham Priory." It became a very popular place for pilgrims to visit.

The priory was unique because it had two communities: canons (male priests) and nuns (religious women) living together. It was closed down in 1538 during a time when many monasteries in England were shut. The Clinton family took over the priory. They completely tore it down, using the building materials to construct a new mansion.

Contents

What Was Sempringham Priory Like?

Sempringham Priory covered a large area of about 80 acres (0.32 km2). It was located on rolling land near the ruins of a big Tudor house, close to the Lincolnshire Fens. The land around the priory was used for farming. For a long time, people didn't know a monastery had been there. But in 1939, archaeological excavations by the Heritage Trust of Lincolnshire found the buried layout of the medieval monastery. They found the housing complex and gardens.

The priory was about 350 feet (110 m) long. It had separate buildings for monks and nuns, built around the 12th century. When it was torn down during the reign of Henry VIII, it was said to be as large as Westminster Abbey.

History of the Priory

How the Gilbertine Order Began

The Gilbertine Order started in 1131. Around that time, Gilbert of Sempringham returned to his home parish church in Sempringham. He was the rector (a type of priest) there. He met seven young women who wanted to live a strict religious life. Gilbert had inherited land and money from his father. He decided to use his wealth to help these women.

With advice from Alexander, the Bishop of Lincoln, Gilbert built some simple buildings and a cloister (a covered walkway) for them. These were built against the north wall of the church, on his own land. He gave them rules for living, focusing on chastity (not marrying), humility (being modest), obedience, and charity (kindness).

At first, their daily needs were passed to them through a window by other girls. But soon, Gilbert's friends suggested that the nuns shouldn't talk to people from outside. So, Gilbert decided to let the serving maids who helped them also join the religious life. Later, he also took on men as lay brothers to work on the land, giving them uniforms and rules too.

The community grew. One of the first people to donate money was Brian of Pointon. In 1139, Gilbert received more land in Sempringham from Gilbert of Ghent, his feudal lord. The first building was too small. So, a new Sempringham Priory was built on this new land, not far from the parish church. It had a double church, cloisters, and other buildings. It was dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Gilbert of Ghent was considered the founder because of his gift.

Becoming an Official Order

In 1147, Gilbert went to a meeting in Citeaux, France. He asked the abbots (leaders of monasteries) there to take charge of his nuns, but they said no. However, at Citeaux, he met Bernard of Clairvaux and Pope Eugene III. The Pope gave Gilbert the responsibility for his new order. Bernard invited Gilbert to Clairvaux and helped him write down the rules for the Order of Sempringham. Pope Eugene III later approved these rules. Gilbert returned to England in 1148. He completed the order by adding canons (priests) to serve the community and help with managing things.

The canons followed the Augustinian rule, with some additions from other orders. The main leaders were the prior, sub-prior, cellarer (who managed supplies), precentor (who led singing), and sacrist (who cared for sacred items). In a double house like Sempringham, there could be between 7 and 30 canons, but at Sempringham, the number grew to 40. The lay brothers followed rules similar to the Cistercian lay brothers. The nuns followed the rule of Saint Benedict and lived by the same customs as the canons.

Each house had three prioresses who led in the frater (dining hall) and visited the sick. Other roles included sub-prioress, cellaress, sacrist, and precentrix. The lay sisters served the nuns. They cooked for everyone, brewed ale, sewed, washed, and made thread and cloth. All clothes, except men's shirts and breeches, were made by the women.

Four people, including the prior, cellarer, and two lay brothers, managed the priory's property. The nuns controlled the spending. Their treasury was in their building, and three trusted nuns each had a different key to it. They communicated about business, food, and other matters through a special window where they couldn't see each other.

The head of the entire order was called the master. He was chosen for life and traveled between all the houses. He appointed the main officers and accepted new members. He also had to approve all sales and purchases of land worth more than three marks. The general meeting of the order happened every year at Sempringham.

Challenges and Changes

While Gilbert was master, there were two big problems. In 1165, Gilbert and all the priors were accused of sending money to Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who was in trouble with the king. This was a false accusation, and they were eventually cleared.

In 1170, some lay brothers rebelled. They complained that the rules were too strict and wanted more food and less work. Two of them even went to Rome and told lies about Gilbert to Pope Alexander III. The Pope believed them at first. But because King Henry II and several bishops supported Gilbert, the Pope realized he had been tricked. The lay brothers eventually asked for forgiveness. So, around 1187, some changes were made to their food and clothing rules.

Gilbert died at Sempringham on February 4, 1189. He was buried in the priory church. Many miracles were reported at his tomb. In 1200, Hubert Walter, the Archbishop of Canterbury, worked to have Gilbert made a saint. After checking the miracles, Pope Innocent III made him a saint. St Gilbert's body was moved on October 13, 1202. Many people came, and pilgrims visiting his shrine were granted special religious favors.

Growing and Trading

At first, the convent of Sempringham was poor. But many people helped the nuns. By 1189, the priory owned a lot of land and churches. Gilbert limited the number of nuns and lay sisters to 120, and canons and lay brothers to 60.

The Gilbertines made most of their money from wool. They had many sheep and sold their wool. Sometimes, they even made the wool into cloth for sale. In 1193, all the wool from the Order of Sempringham for one year was taken to help pay the ransom for King Richard I. The Gilbertines were known for trading wool, even though their own rules and royal orders sometimes told them not to.

Life in the 13th Century

Even with more land, the priory was never very rich. They had many people living there, and their income was small for such a large group. In 1226, King Henry III gave them 100 marks to help. In 1228, he gave them the church of Fordham to help pay for the general chapter meetings.

In 1247, Pope Innocent IV allowed the master to take over the church of Horbling. This was because there were 200 women in the priory who often didn't have enough food. The priory also had to pay a lot for legal costs at the Pope's court.

In 1254, Sempringham's wealth was valued at £170 for spiritual things and £196 9s. 1d. for land and property. The priory was under the special protection of the Pope and didn't have to be inspected by bishops.

In 1223, an inspection of the order found that some rules were being relaxed. For example, nuns' cowls (hoods) were too long, and canons and nuns were using fine furs. They were told to be stricter about silence. The proctors (managers) were ordered to give the nuns the same food and drink as the canons.

Another important inspection happened between 1265 and 1268. It found that the master and heads of houses were sometimes acting unfairly. They were told to rule with love, not fear. They couldn't accept new members without advice from others. They were also told not to sell land or free serfs without asking their fellow proctors and getting approval from their chapters. They were strictly forbidden from trading wool, though this rule was often ignored.

It was also ordered that the nuns should be treated fairly and have all their rights. Money given when a nun joined was to be used for their needs. The master had to make sure they had enough clothes and food.

By 1291, the priory's property value had increased to £219 17s. 11½d. They continued to gain more land. At the start of the 14th century, they sold about 25 sacks of wool each year, which added a lot to their income. Because of their important role in the wool trade, King Edward II asked them for large loans in 1313 and 1315.

The 14th Century: Learning and Trouble

In 1304, the priory decided to set aside some property or income in each house to pay for the frequent taxes from the king and the Pope. The Gilbertines had been free from many taxes before, but they lost these privileges.

The priory also focused on learning. In 1290, Pope Nicholas IV allowed them to have a learned doctor of theology (religious study) to teach the canons. For some years, canons from the order had been sent to study at Cambridge. In 1290, a house was bought in Cambridge for them.

Two years later, Robert Luttrell gave a house and land at Stamford so canons from Sempringham could study divinity and philosophy at the university there. In 1303, a canon named Robert Mannyng of Bourne started writing his book, Handlyng Synne, at Sempringham. It was an English version of a book about sins and vices in society. He had lived in the monastery for 15 years and had studied at Cambridge.

In 1301, Prior John de Hamilton started building a new church for the priory because the old one was falling apart. The Pope had granted special religious favors to people who visited the priory church, so they had money from offerings. They also planned to rebuild other parts of the monastery. But the church was still unfinished in 1342.

The priory faced financial difficulties. The price of corn was very high during the famine years from 1315 to 1321. Also, a yearly payment from Paisley Abbey stopped because of wars. To make up for this loss, the priory was allowed to take over the church of Whissendine in 1319. This church was worth 55 marks and helped pay for clothing 40 canons and 200 women.

Sempringham Priory was favored by the kings Edward I, II, and III because it was the head house of a purely English order. They often sent wives and daughters of their enemies there. Gwenllian, the daughter of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the last Welsh-born Prince of Wales, was sent to Sempringham as a child after her father died in 1283. She died a nun there 54 years later. King Edward I helped the priory get land because he had charged them with her care.

The country was unstable during the reigns of Edward II and Edward III, which was bad for many monasteries. In 1312, Sempringham Priory was attacked by knights who broke in, assaulted the canons, and stole their goods. There were also disputes over land and animals with local lords.

In 1320, the priory was in debt. They owed £1,000 to a clerk. They also had financial problems in 1337 and 1345, struggling to pay the king's taxes. Because of their poverty, the Master of Sempringham was excused from attending Parliament after 1341.

The Black Death (a terrible plague) likely affected Sempringham, though there are no direct records. In 1349, there was a huge storm and flood. The water in the church rose very high, and many books were destroyed. 18 sacks of wool were also damaged. The king then allowed the nuns to take over Hacconby church to help pay for their clothing. It's believed that none of the Gilbertine houses fully recovered from the Black Death. They had to stop farming their own lands and lease them out.

By 1399, the Pope allowed the Gilbertines to lease out their properties to laymen or clerks. This meant they lost their profits from the wool trade, which had been their main source of income. Many sheep died from the plague, making it impossible for them to continue farming and trading successfully.

There were also signs of declining discipline and fewer members. In 1366, the number of nuns had fallen to 67. In 1382, King Richard II allowed the master and priors to arrest canons and lay brothers who ran away. There were also complaints about the master, William of Beverley, who was elected in 1393. He was accused of spending too much and causing problems for the houses.

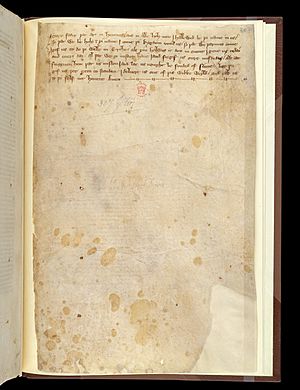

A 14th-century manuscript, which was owned by Sempringham Priory, contains an old version of the Lord's Prayer in Middle English. It reads:

Our Father that art in heavens and in all holy men

Hallowed by thy name in us so that we be holy in thy name

Deliver us out of this wicked world and take us to thy self in heaven. Amen.

. . .

The Final Years: 15th and 16th Centuries

The history of Sempringham Priory in the 15th century is not well known. In 1400, the Pope granted permission for repairs to the priory church. In 1409, money was left to build a bell tower. In 1445, King Henry VI granted some Gilbertine houses, including Sempringham, freedom from all taxes. However, in 1522, Sempringham Priory still had to pay £40 towards King Henry VIII's expenses in France. As farming declined, the need for lay brothers disappeared. They likely died out in the early 15th century, and there is no record of them at the time the priory was closed.

In 1501, a meeting decided that the number of canons should be increased. This attempt to bring new life to the order was somewhat successful. By 1538, there were 143 canons, 139 nuns, and 15 lay sisters in all the Gilbertine houses. The king's visitors found nothing wrong with the Gilbertines in Lincolnshire; they seemed to be living good lives, neither very poor nor very rich.

Robert Holgate, who became master of the order in 1536, tried to prevent the Gilbertine houses from being closed under the Act for the Suppression of Monasteries in 1536. Only four out of 26 houses had incomes over £200 a year, which meant most were considered "smaller monasteries" and were at risk. However, in 1538, no one resisted when Dr William Petre came to take over the monasteries. On September 18, Robert the master, Roger the prior, and 16 canons surrendered Sempringham Priory. The prior received a rectory and £30 a year, and the canons, prioresses, and 16 nuns also received pensions.

In 1535, the priory's yearly value was £317 4s. 1d. A large part of this came from various churches. The rest of the property included farms and lands in many different places across Lincolnshire, Rutland, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, and Derbyshire. Some farms were managed by bailiffs for the monastery, and others were leased out.

Important People Buried Here

- Gwenllian of Wales (daughter of the last Welsh Prince of Wales)

- Saint Gilbert of Sempringham (founder of the Gilbertine Order)

- Henry Beaumont, 3rd Baron Beaumont

- John Beaumont, 4th Baron Beaumont

- Henry Beaumont, 5th Baron Beaumont

Finding the Past: Archaeological Studies

Archaeologists have used special tools like ground-penetrating radar to study the site of Sempringham Priory. This tool can find buried objects without digging. Investigations in the priory area have found not only artefacts from the priory but also 47,000 objects from prehistoric times to after the medieval period. The survey has helped identify the outline of the buildings, including the gatehouse. The foundation walls are said to be in good condition, still hidden beneath the ground.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |