Siege of Oxford facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Oxford |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

A modern-day view of Christ Church, Oxford. King Charles' residence in the city. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Charles I Prince Rupert |

Sir William Waller Sir Thomas Fairfax |

||||||

The siege of Oxford was a series of military attacks on the city of Oxford during the First English Civil War. Oxford was controlled by the Royalists, who supported King Charles I. The attacks happened three times over about two years, and they ended with a victory for the Parliamentarians in June 1646.

The first attack was in May 1644. King Charles I managed to escape, so a full siege didn't happen. The second attack began in May 1645, but it was quickly stopped. The Parliamentarian leader, Sir Thomas Fairfax, was ordered to chase the King instead, leading to the Battle of Naseby. The final siege started in May 1646 and lasted for two months. By this time, the war was almost over. Both sides focused more on talking than fighting. Fairfax was careful not to damage the city too much. He even sent food to the King's second son, James, who was in Oxford. The siege ended peacefully with an agreement.

Contents

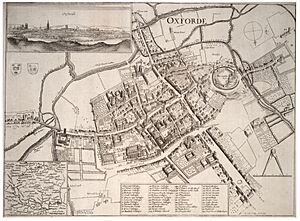

Oxford as the Royalist Headquarters

In January 1644, King Charles I set up his own Parliament in Oxford. This made Oxford the main base for the Royalist forces. This had good and bad points for everyone. Most people in Oxford supported the Parliamentarians. However, supplying the King's court and army gave them ways to make money.

Oxford's location was good for the King. It helped him control the central parts of England. But the city also had problems as a military base. Despite this, ideas to move the King's base were usually ignored. Many people enjoyed the comfortable university buildings. King Charles stayed at Christ Church, and the Queen stayed at Merton. Important government meetings happened at Oriel. St John's housed the French ambassador and two princes, Rupert and Maurice. Other colleges like All Souls and New College were used for storing weapons and supplies. A factory for making cannons was set up at St Mary's College. Mills in Osney made gunpowder. At New Inn Hall, valuable college silver was melted down to make special 'Oxford Crowns' coins.

University life continued, but it was limited. The future kings, Charles II and James II, even received special degrees. During the war, both sides often made mistakes and had bad information. However, there was less hatred between the two sides than you might expect in such a conflict.

First Siege: King Charles Escapes (1644)

In May 1644, Parliamentarian forces led by Sir William Waller and Edmund Ludlow tried to cut off Oxford. On May 27, Waller tried to cross the River Isis at Newbridge, but Royalist soldiers stopped him. The next day, the Earl of Essex and his army crossed the river at Sandford-on-Thames. They stopped on Bullingdon Green, where the city could clearly see them.

On May 29, Parliamentarian horse troops rode near Headington Hill. They had small fights near the city's gates, but not much damage was done. King Charles I watched these movements from the top of Magdalen Tower.

On May 30 and 31, the Parliamentarians tried to cross the River Cherwell at Gosford Bridge, but they failed. Meanwhile, Earl of Cleveland led 150 Royalist horse troops towards Abingdon. They captured 40 prisoners but were chased away.

Waller finally managed to cross the Isis at Newbridge on June 2. A large group of his soldiers crossed the river in boats. King Charles went to Woodstock for a meeting. He soon heard that Waller's troops were very close. The Royalists left their positions at Islip and the Cherwell river crossings. They left burning matches at the bridges to trick the Parliamentarians. The Royalists then went back to Oxford, arriving early on June 3.

There were not enough supplies in Oxford to last long. The King decided he had to leave the city that night. He ordered a large part of his army to march towards Abingdon. This was a trick to distract Waller. The King also set up a council to manage Oxford while he was gone.

On the night of June 3, 1644, around 9 p.m., the King and his son, Prince Charles, left Oxford. They were with many Lords and about 2,500 soldiers. They marched through Wolvercote and Yarnton, reaching Burford by 4 p.m. on June 4. The King's army left their flags standing in Oxford to make it seem like they were still there. Another trick was arranged by 3,500 soldiers left in North Oxford.

The Parliamentarian armies, led by Essex and Waller, were spread out. Essex's troops were near Woodstock, and Waller's were between Newbridge and Eynsham. Even though the King didn't have heavy baggage, he had many carriages. It was surprising that such a large group got away without being seen. The Parliamentarian scouts made big mistakes. Also, Essex and Waller didn't work well together. This allowed the King to escape.

Waller soon found out the King had left. He chased after them and caught a few soldiers in Burford who were "more interested in their drink than their safety." The King and his forces continued to Worcester. A letter from Lord Digby to Prince Rupert on June 17, 1644, showed how big the missed chance was. He wrote that if Essex and Waller had worked together, they would have captured Oxford or the King.

After Essex and Waller failed to capture Oxford and the King, Sergeant-Major General Browne took command of Parliamentarian forces on June 8. He was ordered to take Oxford and other nearby towns. Browne caused a lot of trouble for Oxford after that, but there were no more attempts to capture the city in 1644.

Second Siege: Fairfax Chases the King (1645)

In 1645, one of the first goals for the New Model Army was to block and besiege Oxford. Oliver Cromwell and Browne were supposed to go to Oxford, while Fairfax marched west. Fairfax was in Reading on April 30, 1645. By May 4, he was in Andover, where he was told to stop Prince Rupert from reaching Oxford.

On May 6, Fairfax was ordered to join Cromwell and Browne at Oxford. He also had to send soldiers to help Taunton, which he did by May 12. The Parliament decided to raise money from nearby counties to gather forces to take Oxford. On May 17, they planned to fund Fairfax's efforts to capture Oxford. The goal was to "prevent all Provisions and Ammunition to be brought in."

On May 19, Fairfax arrived near Oxford and showed his troops on Headington Hill. On May 22, he started the siege by building defenses on the east side of the River Cherwell. He also built a bridge at Marston. On May 23, the House of Commons ordered money and supplies for the siege of Oxford. They approved £6,000 for the siege, with £10,000 already waiting at Windsor. They also sent many supplies, including cannons, spades, ladders, gunpowder, and grenades.

According to Sir William Dugdale's diary, Fairfax's troops began crossing the river on May 23. Outbuildings at Godstow House were set on fire, and the Parliamentarians took over the house. On May 26, Fairfax placed four regiments of soldiers near the new bridge at Marston. The King's forces flooded the nearby meadow, burned houses in the suburbs, and set up a guard at Wolvercote. Fairfax himself almost got shot while watching the work.

On May 27, two of Fairfax's regiments marched to Godstow House and then to Hinksey. Important Royalist officials in Oxford marched with their companies to the guards. On the evening of May 29, a cannonball from the Parliamentarians at Marston hit the wall of Christ Church. Meanwhile, Gaunt House near Newbridge was under attack by Colonel Thomas Rainsborough with 600 foot soldiers and 200 horse. The next day, the sound of fighting at Gaunt House could be heard in Oxford. The day after, Rainsborough captured the house and 50 prisoners.

In the early hours of June 2, the Royalist troops in Oxford made a surprise attack. They attacked the Parliamentarian guard at Headington Hill, killing 50 and capturing 96. Many were badly wounded. In the afternoon, Parliamentarian forces took 50 cattle grazing outside the East Gate. On June 3, the prisoners were exchanged. The next day, the siege was stopped, and the bridge over the River Cherwell was taken down.

The Parliamentarian forces left Botley, Hinksey, Marston, and Wolvercote. The reason for this sudden withdrawal was that the King, Prince Rupert, and other important Royalists had left Oxford on May 7. Fairfax, who didn't like long sieges, had convinced the Parliament to let him lift the siege and follow the King. A letter from Fairfax to his father on June 4, 1645, explained his feelings: "I am very sorry we should spend our time unprofitably before a town, whilst the King has time to strengthen himself... It is the earnest desire of this Army to follow the King."

On June 5, Fairfax ended the siege. He had received orders to fight the King and recapture Leicester instead.

Third Siege: Oxford Surrenders (1646)

King Charles returned to Oxford on November 5, 1645, to stay for the winter. The Royalists planned to start fighting again in the spring. They sent Lord Astley to Worcester to gather more soldiers from Wales. However, on his way back, his troops were defeated at Stow-on-the-Wold by Parliamentarian forces. Astley and his officers were captured.

The Parliament in London again ordered its forces to "tighten" their hold on Oxford. On March 18, there was a small fight between Oxford's horse troops and Colonel Charles Fleetwood's men. Two thousand Parliamentarians under Rainsborough came into Woodstock from Witney. On March 30, Rainsborough's soldiers and Fairfax's horse regiments were ordered to "block up Oxford completely." This was to make the people of Oxford use up their stored food and supplies. On April 3, Browne, the Governor of Abingdon, was ordered to send gunpowder to Rainsborough.

On April 4, Colonel Henry Ireton was ordered by Fairfax to join the forces surrounding Oxford. On April 10, the House of Commons discussed how to block Oxford more strictly. They also wanted to guard the roads between Oxford and London. They decided to send a general message asking the King's garrisons to surrender or face punishment.

On April 15, the sound of cannons firing at Woodstock Manor House could be heard in Oxford. Around 6 p.m., Rainsborough's troops attacked but were pushed back. They lost 100 men and their ladders. Many others were wounded. On April 26, the Manor House surrendered. Its Governor and soldiers, without their weapons, returned to Oxford.

The King left Oxford early in the morning of April 27. He didn't tell everyone where he was going. Letters from Colonel Payne, commander of the Abingdon garrison, to Browne reported that the King went to London in disguise. He supposedly used a fake seal from Fairfax. Another letter on April 29 noted common reports of the King's flight: "The news of the king's going to London is constantly confirmed by all that come from Oxford; that he went out disguised in a montero and a hat upon it; that sir Thomas Glemham at his parting bid him 'Farewell Harry', by which name it seems he goes."

On April 30, the House of Commons heard about the King's escape. They ordered that no one could leave Oxford unless it was for talks about surrendering the city. On May 1, Fairfax returned to Oxford to begin the siege, as expected. On May 2, Parliamentarian soldiers entered villages around Oxford, like Headington and Marston. On May 3, the Parliamentarians decided to build a camp on Headington Hill for 3,000 men. They also decided to build a bridge over the River Cherwell at Marston. Fairfax's regiments were placed at Headington, Marston, and Cowley. The artillery was placed at Elsfield. A fourth camp was made on the north side of Oxford. The towns of Faringdon, Radcot, Wallingford, and Boarstall House were completely blocked off. Fairfax's men began to build a line from the 'Great Fort' on Headington Hill towards St Clement's, outside Magdalen Bridge. On May 6, Oxford's food supply was opened. From then on, 4,700 people were fed from it.

On May 11, Fairfax sent a demand for surrender to the Governor: "Sir, I do by these summon you to deliver up the City of Oxford into my hands, for the use of the Parliament. I very much desire the preservation of that place (so famous for learning), from ruin, which inevitably is like to fall upon it, except you concur. You may have honourable terms for yourself and all within that garrison if you reasonably accept thereof. I desire the answer this day, and remain Your servant THO. FAIRFAX."

That afternoon, Prince Rupert was wounded for the first time. He was shot in the arm during a raid north of Oxford. On May 13, the first shot was fired from the 'Great Fort' on Headington Hill. It landed in Christ Church Meadow. The Governor, Sir Thomas Glemham, and his officers told the King's Privy Council that the city could still be defended.

On May 14, the Governor of Oxford, following orders from the Privy Council, sent a letter to Fairfax. He offered to talk on Monday, May 18, and asked for their representatives to meet. Fairfax agreed to the time and place. The Privy Council ordered that all their books and papers about Parliament in Oxford be burned. On May 16, the Governor asked the Lords to prove they had the power to surrender garrisons and raise armies in the King's absence. The Lords signed a paper saying they did have such power. On May 17, the Governor and his officers signed a paper saying they disagreed with the talks. They said they were forced into it by the Privy Council because of the King's orders.

This statement didn't stop the talks. The people of Oxford, who understood the situation better, thought that delaying would be bad. The same day, the Governor sent his agreement and the names of his representatives to Fairfax. Fairfax, in return, sent the names of his representatives.

Treaty Negotiations

Discussions followed about having secretaries for the talks. Fairfax agreed. The first meeting happened at Croke's house on May 18. A letter from N.T. on May 20 complained about the slow pace of the Oxford representatives. The letter ended by saying Fairfax was ready to take the city by force if the talks didn't move faster.

Fairfax sent a first draft of the surrender terms to the House of Commons on May 22. The House of Commons "disdained" these terms. They told Fairfax to continue working to capture Oxford quickly. On May 23, the representatives returned to Marston. According to Dugdale's diary, the Parliamentarians said Oxford's terms were "too high," and so the talks stopped for a while. On May 25, a committee was formed to consider fair surrender terms for Oxford.

On June 15, the House of Commons looked at letters from the King, dated May 18 and June 10. These letters were similar and ordered the governors of Oxford and other towns to give up their cities. The House of Commons ordered that the King's order of June 10 be sent to all governors to "prevent further bloodshed."

Dugdale's diary for May 30 records: "This evening Sir Tho. Fairfax sent in a Trumpet to Oxford, with Articles concerning the delivery thereof." The talks were renewed. The Oxford representatives said they were giving up because of the overall situation in the kingdom, not because they doubted their own strength. The talks restarting happened at the same time as some random cannon fire. Oxford fired 200 shots that day, killing a Parliamentarian colonel. The Parliamentarian cannons fired back fiercely. Eventually, both sides agreed to stop the heavy firing.

On June 1, Fairfax was ready to storm the city if needed. On June 3, Oxford forces made a surprise attack from East Port. About 100 cavalry tried to capture some cattle near Cowley. But Parliamentarian horse troops fought them, and Captain Richardson and two others were killed. On June 4, the representatives met again in Marston to look at Fairfax's new terms.

On June 8, various Oxford gentlemen gave a paper to the Privy Council. They wanted to add specific points to the Treaty. On June 9, the representatives were sworn to secrecy about the talks. On June 10, Fairfax sent a gift of food to the Duke of York (James II) in Oxford. A letter from Fairfax to his father on June 13 stated: "Our Treaty doth still continue. All things are agreed upon concerning the soldiers... The article that took up the greatest debate was about composition. We have accepted of two years' revenue; so that is concluded to. We think Monday will conclude all the rest. I think they do really desire to conclude with us."

On June 17, there was a general stop to fighting. Soldiers from both armies mixed freely. The Privy Council didn't dare meet in their usual place because of angry soldiers. The next day, the clergy and others criticized the Lords of the Privy Council for the terms of the Treaty. The day after, the Lords walked with swords, fearing for their safety. On June 20, the Articles of Surrender, which included terms for university members and citizens, were agreed upon at Water Eaton. They were signed in the Audit House of Christ Church by the Privy Council and the Governor of Oxford, and by Fairfax.

On June 21, the Lords of the Privy Council met with the town's gentlemen. The Lord Keeper gave a speech about the need to finish the Treaty. He read them the authority from the two letters from the King. A newspaper was shown, along with a story about the Scots making the King feel so much pressure that he cried. This also made the Lord Keeper emotional. On June 22, Princes Rupert and Maurice were allowed by Fairfax to leave Oxford and go to Oatlands, even though it went against the Treaty terms. The matter was discussed in the House of Commons on June 26. The Princes were ordered to go to the seaside within ten days and leave the kingdom. Prince Rupert sent a long letter arguing that they didn't break the Treaty.

On June 24, the day the Treaty was supposed to start, the Royalists began leaving Oxford. It wasn't possible to move all the soldiers in one day. But under Article 5, a large group of the regular army, about 2,000 to 3,000 men, marched out of the city with full military honors. Those living in North Oxford left through the North Port. About 900 marched over Magdalen Bridge, between the lines of Parliamentarian troops, and on to Thame. There, they gave up their weapons and were sent away with passes.

Fairfax issued passes that allowed people who were in Oxford during the surrender to travel safely. They could take their servants, horses, weapons, and goods. They were protected from violence and could leave the country within six months.

Although 2,000 passes were given out over a few days, some people had to wait their turn. On June 25, the keys to the city were officially given to Fairfax. Most of the regular Oxford army had left the day before. Fairfax sent in three regiments of soldiers to keep order. The evacuation continued smoothly, and peace returned to Oxford.

See also

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |