Sierra Norte de Puebla facts for kids

The Sierra Norte de Puebla is a rugged, mountainous area in the northern part of the state of Puebla, Mexico. It's where two big mountain ranges meet: the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and the Sierra Madre Oriental. This region sits between the Mexican Plateau and the Gulf of Mexico coast.

For a long time, from ancient Mesoamerican times until the 1800s, this area was part of a larger region called Totonacapan. It was mostly home to the Totonac people. Later, to reduce the Totonacs' power, the region was split between the modern states of Puebla and Veracruz. The Puebla part became known as the Sierra Norte.

Until the 1800s, almost everyone living here was indigenous. The four main groups you still find today are the Totonacs, Nahuas, Otomis, and Tepehuas. But when coffee farming started, mestizos (people with mixed indigenous and European backgrounds) and some European immigrants arrived. They gradually took over the political and economic power.

Even though the area faces many economic challenges, it has developed a lot since the mid-1900s. New roads now connect it to Mexico City and the Gulf coast.

Contents

Exploring the Land: Geography

The Sierra Norte de Puebla includes 68 different towns and villages, and most of them are rural. This region covers about 13% of the state of Puebla.

The area is very mountainous, with about 60% of the land made up of steep slopes. The height above sea level ranges from 100 meters (about 330 feet) to 2,300 meters (about 7,500 feet). There are many caves and caverns here, and some haven't been fully explored yet. The mountains are divided into several smaller ranges like the Sierra de Zacapoaxtla and Sierra de Zacatlán.

Landslides and Rain

The Sierra Norte de Puebla gets a lot of rain and has many steep hills. This makes it prone to landslides. Some towns, like Pahuatlán, are built on old landslide areas. In recent times, people have built heavier homes with cement blocks. This, along with cutting down forests and building roads, has made the risk of landslides even higher. Major landslides have happened many times, sometimes isolating communities for days.

This region is the rainiest part of Puebla. Most places get between 1,500 and 3,000 millimeters (about 59 to 118 inches) of rain each year. Some areas, like Cuetzalan, get even more, up to 6,000 millimeters (about 236 inches)! Most of the water flows in fast-moving streams and small rivers. All these rivers flow towards the Gulf of Mexico.

Nature's Variety

The Sierra Norte has many different kinds of plants and animals because of its varied altitudes. You can find tropical forests, cloud forests (where clouds often cover the trees), and pine-oak forests. Sadly, much of the original forest has been cut down for farms, pastures, or wood. This deforestation also increases the danger of landslides.

Different Zones of the Sierra Norte

The region is divided into four main areas based on its environment and farming:

- Bocasierra: This area is closest to the highlands of Puebla and Tlaxcala. It's cooler here, with heights between 1,500 and 2,500 meters. Farmers grow apples, plums, pears, peaches, and avocados. Important towns include Huauchinango and Zacatlán.

- Coffee-growing region: This area is between 200 and 1,500 meters high. It's very humid and warm, which is perfect for growing coffee and black pepper. Cuetzalan is a well-known town in this zone.

- Zona Baja (Low Area): This is the lowest part, below 200 meters. It has a tropical climate. Farmers grow citrus fruits like oranges and grapefruit, as well as papaya and mamey. Cattle farming is also common here.

- Declive Austral (Southern Slope): This area is drier because the moist winds from the Gulf of Mexico don't reach it as often. Large farms here use advanced watering systems to grow crops like barley and wheat. Horse breeding is also important.

Weather Patterns: Climate

The Sierra Norte is one of the rainiest places in Mexico. It can get between 500 and 800 millimeters (about 20 to 31 inches) of rain every month! This heavy rainfall, especially on the slopes facing the ocean, makes landslides more common as the soil gets very wet.

Hurricanes can hit the area between June and November, at the end of the rainy season. These storms bring huge amounts of rain, causing sudden floods and making the soil so wet that landslides happen. In winter, strong winds called "nortes" bring lighter rain.

The climate has six main types, but generally, it's either hot and humid or temperate and humid, with lots of rain throughout the year or mostly in summer.

The People of the Sierra Norte: Demographics

The Sierra Norte is mostly a rural area with a large indigenous population. Many people here face economic challenges, especially the indigenous communities. People from this region often call themselves "serranos" (mountain people) before identifying with the state of Puebla.

There's a difference between the indigenous groups and "mestizos" (people of mixed European and indigenous heritage). Mestizos mostly live in the bigger towns like Zacatlán and Cuetzalan, while indigenous people live in the more rural areas. Sometimes, indigenous languages and traditions are seen as "not modern" because of the poverty linked to indigenous life. However, groups like the Nahuas and Totonacs have formed organizations to help their communities. One of the first was the Cooperativa Agropecuaria Regional Tosepan Titataniske (CARTT) in the 1970s, which aimed to help small farmers.

Many Cultures in One Place

The Sierra Norte is home to many different ethnic groups, mainly Totonacs, Nahuas, Otomis, and Tepehuas. The National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas) has centers here and even a radio station, XECTZ in Cuetzalan, called "The Voice of the Mountains," which broadcasts in Spanish and various indigenous languages.

Indigenous beliefs and rituals have stayed strong here because the area was quite isolated for a long time. Until the mid-1800s, very few non-indigenous people lived in the region.

The area was originally Totonac land, but over time, other groups like the Nahuas, Otomis, and Tepehuas migrated here. Today, their languages are still spoken alongside Totonac. For many, especially the Nahua, language is a very important part of their identity.

One thing that brings different indigenous groups together is shared religious sites and festivals. For example, Easter celebrations in a Totonac community might also include Nahuas and other neighbors. The Day of the Dead is another important celebration for everyone. People also connect through trade at local markets, which are very important for buying and selling goods.

Traditional Crafts

The tradition of making handcrafts in this region goes back to ancient times. In the past, the Aztecs even demanded cotton clothing as a tribute. Today, people often make crafts to earn extra money, alongside their farming. Many learn these skills as children.

Different communities specialize in different crafts. Pottery is made in towns like Aquixtla and Zacatlán. Textiles, often embroidered, are very common. Women make beautiful blouses, skirts, and a poncho-like garment called a quezquémetl. The designs often vary by community. While men's traditional clothing is less common now, it used to include a cotton shirt and pants, a wrap belt, a pouch, a palm hat, and sandals.

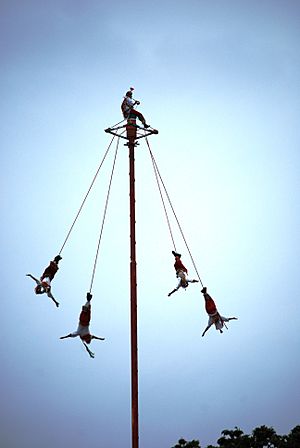

The Dance of the Flyers

The Danza de los Voladores (Dance of the Flyers) is an ancient ceremony that is still performed in the Sierra Norte. In this ritual, five participants climb a tall pole, sometimes 30 meters (about 100 feet) high. Four of them then launch themselves, tied with ropes, and slowly spin down to the ground. The fifth person stays on top of the pole, dancing and playing a flute and drum.

According to one story, this ritual was created to ask the gods to end a severe drought. The exact origin is unknown, but it's believed to have started with the Huastec, Nahua, and Otomi peoples in this region and nearby Veracruz. It was recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2009 to help keep this important tradition alive.

In modern times, some changes have happened. Because many forests have been cut down, most voladores now perform on permanent metal poles. A more recent and sometimes debated change is that a few women have started performing the ceremony, which was traditionally only for men. These women are all in Puebla state, mainly in Pahuatlán and Cuetzalán.

Nahua People

Puebla has the largest number of Nahuas in Mexico, and most of them live in the Sierra Norte. The Nahuas here call themselves Macelhuamej, meaning "true Mexican." There are about 218,000 Nahuas in the region. They are found almost everywhere, sometimes sharing land with other indigenous groups.

Nahuas came to this area through different migrations long ago. Efforts are being made to preserve their language and traditions. For example, an organization in Cuetzalan helped young Nahuas collect myths and stories from their elders to create a book.

Totonac People

The Sierra Norte de Puebla was once part of a larger Totonac region called Totonacapan. Important Totonac ancient sites include El Tajín and Cempoala in Veracruz, and Yohualichan near Cuetzalan. However, the Aztecs invaded Totonac lands, pushing many Totonacs eastward into Veracruz. Because of this, the Totonacs were among the first to ally with the Spanish when they arrived.

After the Spanish conquest, the Spanish initially respected Totonac leaders. But later, they started replacing them with "Indian councils." Diseases also greatly reduced the Totonac population. Today, the Totonac people live in about half the area they did when the Spanish arrived.

Relations between Totonacs and mestizos worsened in the 1700s as mestizos began taking over Totonac lands. There were several revolts, but they were put down. In the 1800s, a revolt happened because a bishop banned traditional Totonac Holy Week celebrations, calling them "pagan." This led to political actions to weaken the Totonacs further.

In the 20th century, the Totonac population continued to decline, and many Totonac speakers switched to Spanish, and sometimes even to Nahuatl. This is often because Spanish is seen as necessary for economic success.

Otomi People

The Sierra Norte Otomi are one of two main Otomi groups in Mexico. They likely came from the Toluca Valley and were pushed north and east by Nahuatl speakers long ago. These Otomis live in some of the steepest and rainiest parts of the Sierra Norte, in small villages.

Most Otomis are subsistence farmers, meaning they grow food mainly for themselves on small plots of land. Family ties are very important. Traditional houses are small, usually with two rooms, but more modern homes are becoming common. The Otomis have kept many of their indigenous beliefs, partly because of their isolation. While they are officially Catholic, traditional healers (shamans) are still important, and religious rituals related to nature and farming are still practiced.

Tepehua People

The Tepehuas are a lesser-known indigenous group found in parts of Hidalgo, Veracruz, and the Sierra Norte, mainly in the municipality of Pantepec. Their language is related to Totonac. Most Tepehuas are farmers, growing basic foods. They earn cash by selling some of their harvest, cash crops like coffee and oranges, and handcrafts. However, poverty is a big problem, and many have moved to other parts of Mexico or the United States for work. Like other groups in the Sierra Norte, the Tepehua have kept much of their religious heritage, but their language is in danger of disappearing.

A Look Back: History

The Totonacs were the first known culture in this area, possibly since the 600s CE. They had big cities like El Tajín and Yohualichan. The powerful city of Teotihuacan also had a strong influence here.

The Sierra Norte was important in ancient times because it connected the Mexican Plateau with the Gulf coast, making it a key trade route. This also attracted different groups of people, especially the Nahuas and Otomis. By the 1400s, the Aztecs took over the area, pushing many Totonacs eastward. The region became a tribute province of Texcoco.

Spanish Arrival and Colonial Times

When the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s, the Totonacs allied with them against the Aztecs. Christian missionaries began their work in 1535, but it was slow. In the early colonial period, the Spanish set up encomiendas (systems to collect tribute) but didn't control the area very strictly because of the rough land and lack of valuable minerals. For centuries, the Sierra Norte remained mostly populated by the same indigenous groups.

Changes in the 1800s and 1900s

The Sierra Norte stayed isolated until the mid-1800s, when cash crops like coffee and ways to transport them were introduced. Railways came in the late 1800s, making it profitable to ship coffee, sugar cane, and fruit to Mexico City. This attracted Mexican mestizos and some European immigrants from Spain and Italy. These new groups often took over land from the indigenous people. This led to a new political setup, with a mostly mestizo elite in the main towns and indigenous people in the rural areas.

This situation, along with Totonac rebellions, led to the political division of the old Totonacapan region between Puebla and Veracruz. The Puebla part became known as the Sierra Norte. The borders of northern Puebla changed a few times in the late 1800s but were set to their current lines by the Mexican Revolution.

The 20th century, after the Revolution, saw the region become more connected and modern. The most important change was the building of highways, making the area much more accessible. Before, many communities could only be reached by air, foot, or horse. Now, most are accessible by car, even if it's just a dirt road.

Education also improved greatly in the 20th century. Public schools became widely available in the 1960s. Most towns now offer education up to middle school, and many have high schools. Access to education has led many young people to leave the area for better opportunities elsewhere.

Another big improvement was the introduction of electricity and running water, even in isolated communities. This was possible because the region has many hydroelectric resources (power from water).

Despite these improvements, the region still faces challenges. Drainage and sewage systems are still scarce. The new roads also made the cash economy, driven by coffee farming, more important. While this brought money for things like televisions, it also made cash a necessity for food and other goods. When coffee prices dropped in the 1980s, many people had to leave the area, temporarily or permanently, to find work in other parts of Mexico or the United States.

How People Make a Living: Economy

The Sierra Norte has many economic challenges. In the past, this was due to its isolation. Now, it's more related to the cash economy. These challenges are most severe in the rural indigenous areas, where wealth and power are concentrated in the bigger towns controlled by mestizos. Because of the need for cash and lack of jobs, many people have left the region, either temporarily or permanently. Seasonal workers often go to Mexico City, Puebla, or Veracruz to work in farming or construction. Since the 1980s, many have also gone to the United States for work.

Farming and Crops

The main economic activity is farming, mostly growing corn, beans, and other foods for families to eat themselves. Other crops include potatoes, chili peppers, sugar cane, citrus fruits, bananas, plums, apples, and peaches.

Puebla is the fourth largest producer of coffee in Mexico, and most of it comes from the Sierra Norte. This region produces 97% of Puebla's total coffee. Coffee provides important income for both large farms and small family businesses. Most coffee is grown under shade trees, which helps protect the native trees. Besides coffee, other cash crops include black pepper, mamey, vanilla, and medicinal herbs. Flower farming is also very important in some towns like Huauchinango.

However, because most farms are small and lack modern technology, they often can't compete with other regions in Mexico. Low coffee prices since the 1980s have also caused farmers to switch to other crops.

Crafts and Industry

Industry in the area mostly involves family workshops making handcrafts, along with some small factories. Chignahuapan is Mexico's biggest producer of blown glass Christmas tree ornaments, with 400 workshops making 70 million ornaments each year!

The handcrafts tradition is very old. Communities often specialize in certain crafts. Pottery is made in towns like Aquixtla and Zacatlán. Textiles, often embroidered, are made more widely.

In the 1970s, the Otomi people of San Pablito, Pahuatlán started making amate (bark paper) to sell. This paper has become very popular and is sold both in Mexico and internationally. However, making amate can harm the environment because trees are stripped for bark and chemicals can pollute rivers. Efforts are being made to plant new trees and use less polluting chemicals.

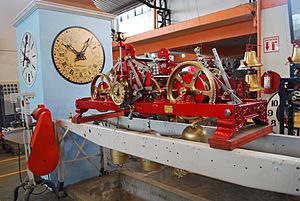

Zacatlán is known for making hard apple cider and fruit wines. It also has two factories: one that makes pistols and Relojes Centenario, Mexico's most famous maker of large clocks for buildings. Some maquiladoras (factories that assemble products) have also opened in the region.

Mining also takes place in Teziutlán, where minerals like magnesium, iron, and clay are found. PEMEX, Mexico's oil company, has pumping stations in the region, especially around Huauchinango.

Tourism

Since the late 1900s, the government has been promoting tourism here to help the economy. This tourism focuses on the region's natural beauty and indigenous culture. The goal is to protect nature while allowing economic growth. Nature tourism activities include visiting rural towns, hiking, camping, and recreational fishing.

Much of the investment in tourism has gone to the main towns, especially Zacatlán and Cuetzalan. Both have been named "Pueblos Mágicos" (Magical Towns), which means they are special places for tourists. To get this title, both cities underwent big restoration projects.

Indigenous culture is also promoted through new festivals. For example, Pahuatlán hosted an exhibition for Voladores performers to promote the area's culture.

Some indigenous people have also benefited from tourism. Masseualsiuamej Mosenyolchicauanij (Women who work together) is a Nahua cooperative that makes and sells handcrafts. In 1997, they even opened their own hotel and ecotourism center called Taselotzin, which is entirely owned and run by these women.

Learning and Growth: Education

Widespread public education only became available in the Sierra Norte in the 1960s. Today, all towns offer education up to middle school, and most have high schools.

There are also several institutions for higher education (college) in the region. The Universidad de la Sierra is a private university in Huauchinango. Teziutlán has campuses of the Universidad Pedagógica Nacional and the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, which help students who can't leave the area to go to college.

See also

In Spanish: Sierra Norte de Puebla para niños

In Spanish: Sierra Norte de Puebla para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |