Sinking of SS Princess Alice facts for kids

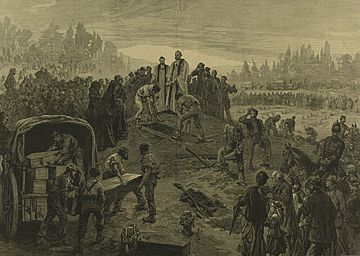

Artist's impression of the collision

|

|

| Date | 3 September 1878 |

|---|---|

| Time | Between 7:20 pm and 7:40 pm |

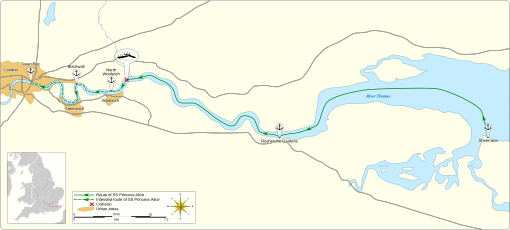

| Location | Gallions Reach, River Thames, England |

| Cause | Collision |

| Casualties | |

| 600 to 700 dead | |

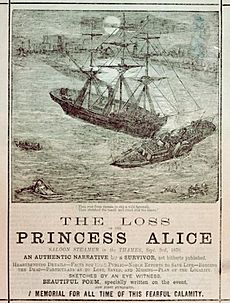

The SS Princess Alice, originally named PS Bute, was a British passenger paddle steamer. It sank on September 3, 1878, after crashing into a coal ship called SS Bywell Castle on the River Thames in England. This terrible accident caused the deaths of between 600 and 700 people, all from the Princess Alice. It was the worst loss of life ever in a British inland waterway shipping accident. Because no passenger list was kept, the exact number of people who died is still unknown.

Princess Alice was built in Greenock, Scotland, in 1865. For two years, she carried passengers in Scotland. Then, the Waterman's Steam Packet Co. bought her to carry passengers on the Thames. By 1878, the London Steamboat Co owned her, and Captain William R. H. Grinstead was her master. The ship offered trips from Swan Pier, near London Bridge, down to Sheerness, Kent, and back.

On her return journey, about an hour after sunset on September 3, 1878, Princess Alice passed Tripcock Point and entered Gallions Reach. She took a wrong path and was hit by Bywell Castle. The collision happened in an area of the Thames where a huge amount of London's raw sewage (about 75 million gallons) had just been released. Princess Alice broke into three pieces and sank very quickly. Her passengers drowned in the heavily polluted water.

Captain Grinstead died in the accident, so later investigations could not find out why he chose that path. A group of people called a jury, who looked into the deaths, thought both ships were at fault. However, they blamed Bywell Castle more. Another investigation by the Board of Trade found that Princess Alice had not followed the correct path, and her captain was responsible. After the sinking, rules changed about how sewage was released and treated. It was then transported and released into the sea instead. The Marine Police Force, which looked after the Thames, received steam launches. Their old rowing boats had not been good enough for rescues. Five years after the collision, Bywell Castle sank in the Bay of Biscay, and all forty crew members were lost.

About the Ships

The Princess Alice

The passenger paddle steamer Bute was built by Caird & Company in Greenock, Scotland, and launched on March 29, 1865. She started service on July 1, 1865. The ship was about 67 meters (219.4 feet) long and 6.1 meters (20.2 feet) wide. She weighed 432 gross registered tons. Bute was built for the Wemyss Bay Railway Company. She carried passengers between Wemyss Bay and Rothesay.

In 1867, she was sold to the Waterman's Steam Packet Co. to work on the River Thames. The company renamed her Princess Alice, after Queen Victoria's third child. In 1870, she was sold again to the Woolwich Steam Packet Company and used for fun trips. This company later changed its name to the London Steamboat Company. In 1873, the ship carried Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, the Shah of Persia, up the Thames to Greenwich. Because of this, many local people called her "The Shah's boat."

When the Woolwich Steam Packet Company bought Princess Alice, they made some changes. They put in new boilers and made the five inside walls (bulkheads) watertight. The Board of Trade inspected the ship and said it was safe. In 1878, another inspection by the Board of Trade allowed the ship to carry up to 936 passengers between London and Gravesend in calm water.

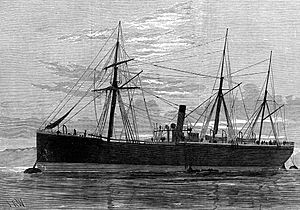

The Bywell Castle

The coal ship SS Bywell Castle was built in Newcastle in 1869. It was owned by Messrs Hall of Newcastle. She weighed 1376 gross registered tons. She was about 77.5 meters (254.2 feet) long and 9.8 meters (32 feet) wide. Her hold was about 5.8 meters (19 feet) deep. Her captain was Thomas Harrison.

The Day of the Accident: September 3, 1878

On September 3, 1878, Princess Alice was on a special "Moonlight Trip." She sailed from Swan Pier, near London Bridge, down to Sheerness, Kent, and back. During the trip, she stopped at Blackwall, North Woolwich, and Rosherville Gardens. Many Londoners on board were going to Rosherville to visit the pleasure gardens built 40 years earlier. The London Steamboat Co. owned several ships, so passengers could use their tickets on different boats that day. A ticket from Swan Pier to Rosherville cost two shillings.

Princess Alice left Rosherville around 6:30 pm to return to Swan Pier. She was almost full of passengers, but no lists were kept, so the exact number of people on board is not known. The captain of Princess Alice, 47-year-old William Grinstead, let his regular helmsman stay at Gravesend. He replaced him with a passenger, a sailor named John Ayers. Ayers did not know the Thames very well, and he wasn't used to steering a ship like Princess Alice.

Between 7:20 pm and 7:40 pm, Princess Alice had passed Tripcock Point and entered Gallions Reach. She was close to North Woolwich Pier, where many passengers were going to get off. That's when Bywell Castle was seen. Bywell Castle usually carried coal to Africa, but she had just been repainted in a dry dock. She was going to Newcastle to pick up coal for Alexandria, Egypt. Captain Harrison was not familiar with the river conditions, so he hired Christopher Dix, an experienced Thames river pilot, even though he didn't have to. Since Bywell Castle had a raised front part (forecastle), Dix couldn't see clearly in front of him, so a sailor was placed on lookout.

After leaving Millwall, Bywell Castle sailed down the river at five knots (about 9 kilometers per hour). She stayed mostly in the middle of the river, moving only for other boats. As she neared Gallions Reach, Dix saw Princess Alice's red port (left) light. This meant she was coming towards them on a path that would pass on their right side. Captain Grinstead, sailing upriver against the tide, followed the usual practice for river boats. He tried to find the calmer water on the south side of the river. He changed the ship's course, which put her directly in the path of Bywell Castle.

Seeing the crash was about to happen, Grinstead shouted to the larger ship, "Where are you coming to! Good God! Where are you coming to!" Dix tried to move his ship away from the collision and ordered the engines to go "reverse full speed," but it was too late. Princess Alice was hit on her right side, just in front of the paddle wheel, at an angle of 13 degrees. She broke into two parts and sank within four minutes. Her boilers separated from the ship as it went down.

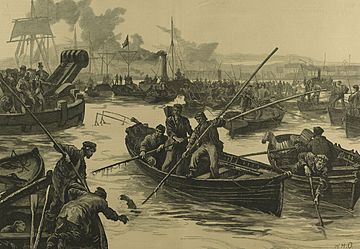

The crew of Bywell Castle threw ropes from their deck for Princess Alice passengers to climb. They also threw anything that could float into the water for people to hold onto. Other crew members from Bywell Castle launched their lifeboat and rescued 14 people. Crews from nearby boats also helped. People living on both sides of the Thames, especially boatmen from local factories, launched their boats to rescue anyone they could. Many passengers from Princess Alice could not swim. The long, heavy dresses worn by women also made it hard for them to stay afloat. Princess Alice's sister ship, Duke of Teck, was about ten minutes behind her. She arrived too late to rescue anyone still in the water. Only two people who had been below decks or in the main cabin survived the crash. A diver who later checked the main cabin said that the passengers were stuck together in the doorways, mostly still standing.

About 130 people were rescued from the collision. However, several of them later died from swallowing the polluted water. Princess Alice sank at the exact spot where London's sewage pumping stations were located. Twice a day, about 75 million gallons of raw sewage were released from the sewer outlets at Abbey Mills, in Barking, and the Crossness Pumping Station. This release had happened just one hour before the collision.

The water was also polluted by waste from the Beckton Gas Works and several local chemical factories. To make the water even worse, a fire in Thames Street earlier that day had caused oil and petroleum to spill into the river.

Bywell Castle docked at Deptford to wait for the authorities and the investigation.

After the Disaster

Finding the Victims

News of the sinking was sent by telegraph to central London. Soon, it reached those waiting at Swan Pier for the ship to return. Relatives went to the London Steamboat offices near Blackfriars to wait for more news. Many took the train from London Bridge to Woolwich. Crowds grew through the night and into the next day, as both relatives and people curious to see what happened traveled to Woolwich. More police were brought in to help control the crowds and deal with the bodies that were being brought ashore. Reports came in of bodies washing up as far upstream as Limehouse and down to Erith.

When bodies were brought ashore, they were kept in different local places for identification, not all in one central spot. Most ended up at Woolwich Dockyard. Relatives had to travel between several places on both sides of the Thames to search for missing family members. Local boatmen were paid £2 a day to search for bodies. They also received at least five shillings for each body they found, which sometimes led to arguments over the bodies. One of the bodies found was that of Captain Grinstead, Princess Alice's captain.

Because of the pollution from sewage and local factories, the bodies from the Thames were covered in a slimy substance that was hard to clean off. The bodies began to decay faster than normal, and many were unusually swollen. Victims' clothes also rotted quickly and changed color after being in the polluted water. Sixteen of those who survived died within two weeks, and several others became ill.

The Investigations

On September 4, Charles Carttar, the person in charge of investigating deaths (the coroner) for West Kent, started his investigation for his area. That day, he took the jury to see the bodies at Woolwich Town Hall and Woolwich Pier. There were more bodies on the northern bank, but this was outside his area. Charles Lewis, the coroner for South Essex, visited the Board of Trade and the Home Office. He tried to have the bodies in his area moved to Woolwich so one investigation could cover all the victims. However, the law meant the dead could not be moved until the investigation had officially started and then paused. Instead, he started his investigation to officially identify the bodies under his authority. Then, he paused it until Carttar's case was finished. He gave permission for burials, and the bodies were then moved to Woolwich.

At low tide, part of Princess Alice's railing could be seen above the water. Plans to raise the ship began on September 5, with a diver checking the wreckage. He found the ship had broken into three parts: the front, the back, and the boilers. He reported that there were still several bodies inside. Work began the next day to raise the larger front section, which was about 27.4 meters (90 feet) long. This part was brought ashore at low tide—2:00 am on September 7—at Woolwich. While it was being pulled ashore, Bywell Castle sailed past, leaving London, but without her captain, who stayed behind. The next day, large crowds visited Woolwich again to see the raised part of Princess Alice. Fights broke out in some places for the best view, and people rowed up to the wreck to break off souvenirs. An extra 250 police officers were brought in to help control the crowds. That evening, after most of the crowd had left, the back section of the ship was raised and brought ashore next to the front part.

Because many of the bodies were decaying very quickly, the burials of those still not identified took place on September 9 at Woolwich cemetery in a large shared grave. Several thousand people attended. All the coffins had a police identification number, which was also attached to the clothing and personal items kept to help identify people later. On the same day, over 150 private funerals for victims also took place.

The first two weeks of Coroner Carttar's investigation focused on officially identifying the bodies and visiting the wreck site to examine the remains of Princess Alice. From September 16, the investigation began to look into the causes of the collision. Carttar started by complaining about how the news had covered the event, which strongly suggested Bywell Castle was wrong and should be blamed. He focused his investigation on William Beechey, the first body to be clearly identified. Carttar explained to the jury that whatever decision they made about Beechey would apply to the other victims. Many Thames boatmen who were in the area at the time appeared as witnesses. Their stories about the path Princess Alice took were very different.

Most pleasure boats going upriver on the Thames would go around Tripcock Point and head for the northern bank to use the stronger currents. If Princess Alice had done that, Bywell Castle would have passed clearly behind her. Several witnesses said that once Princess Alice went around Tripcock Point, currents pushed her into the middle of the river. The ship then tried to turn left (to port), which would have kept her close to the river's southern bank, but in doing so, she cut across the front of Bywell Castle. Several captains of other ships nearby who saw the collision agreed with this series of events. Princess Alice's chief mate denied that his ship had changed direction.

Evidence was also taken about the condition of the Thames where the ship sank, and about how Princess Alice was built and how stable she was. On November 14, after twelve hours of discussion, the investigation released its decision. Four of the nineteen jury members refused to sign the statement.

Board of Trade Investigation

At the same time as the coroner's investigation, the Board of Trade held its own inquiry. Specific accusations were made against Captain Harrison, two crew members of Bywell Castle, and against Long, the first mate of Princess Alice. All of them had their licenses temporarily stopped at the start of the hearing. The Board of Trade proceedings began on October 14, 1878, and continued until November 6. The board found that Princess Alice had broken Rule 29, Section (d) of the Board of Trade Regulations and the Regulations of the Thames Conservancy Board, 1872. This rule stated that if two ships are heading towards each other, they should pass on each other's left (port) side. Since Princess Alice had not followed this rule, the Board found Princess Alice to blame and that Bywell Castle could not have avoided the collision.

The company that owned Princess Alice sued the owners of Bywell Castle for £20,000 in damages. The owners of Bywell Castle sued back for £2,000. The case was heard in the Admiralty Division of the High Court of Justice in late 1878. After two weeks, the judgment was that both ships were responsible for the collision.

Since no passenger list was kept on Princess Alice—or a record of how many people were on board—it was impossible to know the exact number of people who died. Figures range from 600 to 700. The Times newspaper reported that "the coroner believes that there are from 60 to 80 bodies unrecovered from the river. The total number of lives lost must thus have been from 630 to 650." Michael Foley, who studied disasters on the Thames, noted that "there was no proof of the final death toll. However, around 640 bodies were eventually recovered." The sinking was the worst inland water disaster in the UK.

A fund for the victims was started by the Lord Mayor of London after the sinking. By the time it closed, it had collected £35,000, which was given to the victims' families.

What Changed After the Disaster

During the 1880s, London's Metropolitan Board of Works started to clean the sewage at Crossness and Beckton instead of just dumping the untreated waste into the river. They ordered six special boats to carry the treated waste into the North Sea for dumping. The first boat, launched in June 1887, was named Bazalgette, after Joseph Bazalgette, who had rebuilt London's sewer system. This practice of dumping at sea continued until December 1998.

Before Princess Alice sank, the Marine Police Force, which was the part of the Metropolitan Police responsible for policing the Thames, used rowing boats for their work. The investigation into the sinking of Princess Alice found that these boats were not good enough for the job. It was decided they should be replaced by steam launches. The first two steam launches started working in the mid-1880s, and by 1898, eight were in use. The Royal Albert Dock, which opened in 1880, helped separate large cargo ships from smaller boats. This, along with the worldwide use of emergency signaling lights on boats, helped prevent future tragedies.

After 23,000 people donated to a fund that cost sixpence per donation, a memorial Celtic cross was put up in Woolwich Cemetery in May 1880. St Mary Magdalene Woolwich, the local church, also later put in a stained-glass memorial window. In 2008, a National Lottery grant helped pay for a memorial plaque at Barking Creek to mark 130 years since the sinking.

The London Steamboat Co, which owned Princess Alice, bought the wreck of the ship from the Thames Conservancy for £350. The engines were saved, and the rest of the ship was sent to a ship breaker. The London Steamboat Co went out of business within six years, and the company that took over also faced financial problems three years after that. According to historian Jerry White, along with competition from railways and bus services, the sinking of Princess Alice "had some impact... in making the tidal Thames less popular as a place for fun." Bywell Castle was reported missing on January 29, 1883, while sailing between Alexandria and Hull. It was carrying cottonseed and beans.

More to Explore

- List of disasters in Great Britain and Ireland by death toll

- List of maritime disasters in the 19th century

- Marchioness disaster

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |