Soil formation facts for kids

Soil formation, also known as pedogenesis, is how soil is made. It's a natural process shaped by the place, environment, and history of an area. Tiny changes happen in the soil, creating different layers called soil horizons. These layers look different in color, structure, texture, and chemistry.

Studying soil formation helps us understand why different types of soil are found in certain places today and in the past.

Contents

How Soil Forms

Soil starts to form when rocks and other materials break down. This breaking down is called weathering. Many tiny living things in the soil, like bacteria and fungi, help break down these materials. They eat simple compounds and create acids that further break down minerals. They also leave behind organic stuff that helps make humus, which is rich, dark organic matter in soil. Plant roots and their helpful fungi also pull nutrients from rocks.

New soil gets deeper as more material breaks down and new stuff is added. Soil can grow about 1/10 of a millimeter each year from weathering. It can also get deeper from dust blowing in and settling.

Over time, soil can support more complex plants and animals. The first plants to grow are called pioneer species. As the soil develops, more complex communities of plants and animals move in. The topsoil gets deeper as dead plants and microbes add humus. It also deepens when organic matter mixes with weathered minerals. As soil gets older, it forms distinct layers, or soil horizons, as organic matter builds up and minerals break down and wash away.

What Makes Soil Form?

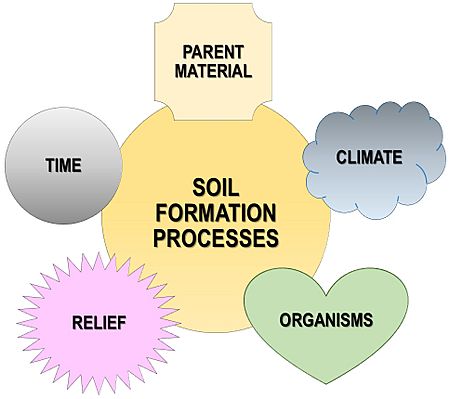

Soil formation is influenced by five main things. These are often remembered by the acronym CLORPT:

- Climate

- Organisms

- Relief (or topography)

- Parent material

- Time

Parent Material: The Starting Rock

The original rock or mineral material that soil forms from is called parent material. This rock can be igneous (from volcanoes), sedimentary (from layers of sediment), or metamorphic (changed by heat and pressure). It's the source of almost all the minerals and nutrients plants need, except for nitrogen, hydrogen, and carbon. As parent material breaks down and moves, it changes into soil.

Common minerals found in parent material include:

Parent materials are grouped by how they were deposited.

- Residual materials are rocks that broke down right where they were.

- Transported materials were moved by water, wind, ice, or gravity.

- Cumulose material is organic matter that grew and built up in one place.

Most soils come from transported materials.

- Wind can move fine sand and silt for hundreds of miles, creating loess soils. These soils are common in places like the Midwest of North America.

- Water moves materials in rivers (alluvial), lakes (lacustrine), or seas (marine). For example, soils around the Great Lakes in the United States are lacustrine deposits.

- Ice (glaciers) move parent material and leave behind piles of rock and soil called moraines.

- Gravity moves material down steep slopes, forming piles of rock and soil called colluvial material.

Cumulose parent material, like peat and muck soils, forms from dead plants in wet, low-oxygen areas.

How Rocks Break Down (Weathering)

weathering is how parent material turns into soil. It happens in three ways:

- Physical weathering: Rocks break into smaller pieces.

- Chemical weathering: Minerals in rocks change their chemical makeup.

- Chemical transformation: Minerals change their structure.

Weathering usually happens in the top few meters of the ground.

- Physical breaking down starts when rocks deep underground are exposed to less pressure near the surface. They expand and crack. Water can get into these cracks and freeze, splitting the rock. Cycles of wetting and drying also break down soil particles. Plants and animals also help by growing roots into cracks or digging.

- Chemical changes happen when minerals dissolve in water or change their structure.

- Solution: Salts in rocks dissolve in water, making the rock weaker.

- Hydrolysis: Water breaks down minerals into new, more soluble compounds.

- Carbonation: Carbon dioxide in water forms carbonic acid, which can dissolve minerals like calcite.

- Hydration: Water becomes part of a mineral's structure, making it swell and easier to break down.

- Oxidation: Oxygen combines with minerals, making them swell and easier to break down. This is like rust forming on metal.

- Reduction: The opposite of oxidation, this happens when oxygen is scarce, like in wet, waterlogged soils. Minerals become unstable and break down.

Saprolite is a type of soil that forms when granite and other rocks turn into clay minerals. This happens through a mix of chemical and physical weathering processes.

Climate: Weather's Role

The main climate factors affecting soil formation are how much rain falls (and stays in the soil) and the temperature. Both affect how fast chemical, physical, and biological processes happen. Temperature and moisture also influence how much organic matter is in the soil. Colder or drier climates usually have less organic matter.

Climate is a very important factor. Soils often look different depending on the climate zone they are in. If it's warm and wet, weathering, leaching (washing away of minerals), and plant growth happen faster. Humid climates are good for trees, while drier areas have more grasses or shrubs.

Water is vital for chemical weathering. The more water that soaks into the ground, the deeper the soil can develop. Water moving through the soil carries dissolved and suspended materials from upper layers (eluviation) to lower layers (illuviation). This helps create different soil layers. In dry regions, water is scarce, so soluble salts don't wash away and can build up.

Direct effects of climate include:

- Lime building up in dry areas (called caliche).

- Acidic soils forming in humid areas.

- Erosion on steep hillsides.

- Intense chemical weathering in warm, humid regions.

Wind also moves sand and dust, especially in dry areas with little plant cover. Temperature changes, like freezing and thawing, also break up rocks.

Climate also affects soil indirectly through the plants and animals that live there, which change how fast chemical reactions happen in the soil.

Topography: The Shape of the Land

Topography means the shape of the land, including its slope, elevation, and direction it faces (aspect). Topography affects how much rain runs off and how fast soil forms or erodes.

Steep slopes often lose soil quickly due due to erosion. Less rain soaks in, and there's less plant cover. So, soils on steep slopes are usually shallow and not well-developed.

The shape of the land also affects how much sun, fire, and other forces the soil gets. Soils at the bottom of a hill get more water than those on slopes. Slopes facing the sun will be drier.

In low areas and depressions, water collects, so the soil is usually more deeply weathered. However, if water saturates the ground too much, it can slow down the breakdown of some minerals and organic matter. This can lead to special features found in wetland soils.

Organisms: Living Things in the Soil

Every soil has a unique mix of microbes, plants, animals, and human influences. Microorganisms are very important for changing minerals in the soil. Some bacteria can take nitrogen from the air, and some fungi help plants get phosphorus. Plants hold soil in place and add organic matter when they die. Animals help break down plant materials and mix the soil.

Soil is full of life, mostly tiny microbes. There can be billions of cells in just one gram of soil!

Animals like earthworms, ants, termites, and moles mix the soil as they dig burrows. This creates pores that let water and gases move through. This mixing is called bioturbation. Plant roots also grow through the soil, creating channels when they decompose. Deep-rooted plants can bring nutrients up from lower layers. Plants also release organic compounds that feed microbes, creating a busy area around the roots called the rhizosphere.

Humans also affect soil formation. Removing plant cover through farming, using chemicals, or burning can lead to erosion or waterlogging. Farming practices like tillage (plowing) mix different soil layers, which can restart the soil formation process.

Earthworms are especially important. They eat soil and organic matter, making nutrients more available. They also aerate the soil and create stable soil clumps. Ants and termites also build mounds, moving soil from one layer to another.

In general, animals mixing the soil (pedoturbation) can work against other processes that create distinct soil layers.

Plants affect soil in many ways. They prevent erosion, shade the soil, and slow down water evaporation. They also release chemicals that break down minerals and improve soil structure. When plants die, their leaves and stems decompose on the surface, adding organic matter to the soil.

Humans can greatly change soil formation. For example, overgrazing by animals can speed up soil erosion. Ancient people in the Amazon basin created very fertile soils called Terra Preta by adding charcoal and organic matter.

Time: How Long It Takes

Time is a factor because all the other factors interact over time. It takes many years for soil to develop distinct layers. This time depends on the climate, parent material, land shape, and living things. For example, new material from a flood won't have developed soil layers yet.

Soil-forming factors continue to affect soils throughout their existence, even on stable landscapes that have been around for millions of years. Materials are added, removed, and changed, so soils are always changing. These changes can be slow or fast, depending on climate, topography, and biological activity.

Scientists study how soil changes over time by looking at chronosequences. These are soils of different ages that have similar other soil-forming factors.

How We Learned About Soil Formation

Dokuchaev's Idea

Vasily Dokuchaev, a Russian geologist, is often called the father of soil science. In 1883, he figured out that soil forms over time because of climate, plants, land shape, and parent material. He showed this with a simple equation:

- soil = f(climate, organisms, parent material) relative time

Hans Jenny's Equation

In 1941, American soil scientist Hans Jenny published his own equation for soil formation:

- S = f(cl, o, r, p, t, …)

- S stands for soil formation.

- cl (or c) is climate.

- o is organisms.

- r is relief (land shape).

- p is parent material.

- t is time.

This equation is often remembered by the word CLORPT. Jenny's equation added relief and time as specific factors. The "..." means that there might be even more factors we don't fully understand yet.

Scientists still use Jenny's ideas today to understand how different factors create the soil patterns we see around the world.

Key Soil-Forming Processes

Soils develop from parent material through different weathering processes. Also, organic matter building up, breaking down, and turning into humus are very important. The area where these processes are most active and where living things play a big role is called the solum.

Plants help break down minerals through their roots.

Soils can also get richer from new sediment being deposited by floods or by wind-blown dust.

Soil mixing, or pedoturbation, is also a big part of soil formation. This includes things like:

- Churning clays: When certain clays expand and shrink, they mix the soil.

- Cryoturbation: Mixing caused by freezing and thawing.

- Bioturbation: Mixing by animals digging or plant roots growing.

Pedoturbation mixes the soil layers and creates paths for air and water to move through.

Water moving through the soil helps leach (wash out) dissolved materials and move tiny particles like clay. These materials are then deposited in lower layers. This movement and deposition create the different soil layers we see.

Some important soil-forming processes that create large-scale soil patterns include:

- Laterization (forming hard, iron-rich layers in tropical soils)

- Podsolization (forming ash-colored layers in cool, wet climates)

- Calcification (building up calcium carbonate in dry areas)

- Salinization (building up salts in dry areas)

- Gleization (forming gray or mottled soils in wet, low-oxygen conditions)

See also

In Spanish: Pedogénesis para niños

In Spanish: Pedogénesis para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |