Tuatara facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tuatara |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Northern tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus punctatus) | |

| Conservation status | |

|

Invalid status (NZ TCS)

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Sphenodon

|

| Species: |

punctatus

|

|

|

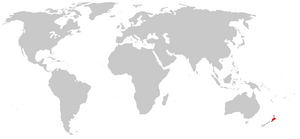

| Native range (New Zealand) | |

|

|

| Current distribution of tuatara (in black): Circles represent the North Island tuatara, and squares the Brothers Island tuatara. Symbols may represent up to seven islands. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

The tuatara (scientific name: Sphenodon punctatus) is a very special reptile. It lives only in New Zealand and nowhere else in the world.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name tuatara comes from the Māori language. It means "peaks on the back," which describes the spiky ridge on their backs.

About Tuatara: Appearance and Body

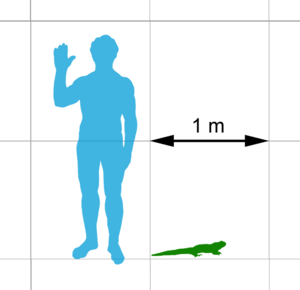

Adult male tuatara can grow up to 61 cm (24 in) long. Females are a bit smaller, reaching about 45 cm (18 in). Males are also heavier, weighing up to 1 kg (2.2 lb), while females weigh up to 0.5 kg (1.1 lb).

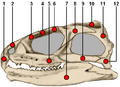

Tuatara have a unique mouth. They have two rows of teeth on their upper jaw. These teeth overlap one row on their lower jaw. This special setup helps them slice through tough insect shells and bones. What's even more amazing is that their teeth don't grow back! As tuatara get older, their teeth wear down. This means older tuatara have to eat softer foods, like earthworms or slugs.

Their skin is usually greenish-brown, which helps them blend in with their surroundings. Tuatara shed their skin at least once a year as adults. Young tuatara shed their skin more often. Males have a larger, spiky crest on their back. They can make this crest stiff to show off.

Tuatara Behavior

Adult tuatara are usually active at night. However, they often warm themselves in the sun during the day.

Baby tuatara hide under logs and stones to stay safe. They are active during the day. This is because adult tuatara sometimes eat younger ones. Tuatara can live in much colder temperatures than most other reptiles. They even stay active when it's as cold as 5 °C (41 °F). If it gets too hot, over 28 °C (82 °F), it can be dangerous for them.

Their body temperature is lower than most reptiles. This means their bodies work more slowly. They even hibernate during the winter months.

Where Tuatara Live and What They Eat

Tuatara often share their island homes with seabirds like petrels. They sometimes use the birds' burrows for shelter. If no burrows are available, they dig their own.

The birds' droppings help bugs and other small creatures grow. These creatures are the main food for tuatara. Their diet includes beetles, spiders, and earthworms. They also eat frogs, lizards, and even bird eggs and chicks. Sometimes, young tuatara are eaten by older tuatara.

In the summer, tuatara mainly eat fairy prions and their eggs. Eating seabird eggs and young birds might give tuatara important fats.

Tuatara Life Cycle and Reproduction

Tuatara grow up very slowly. It takes them 10 to 20 years to become old enough to have babies.

Mating happens in the middle of summer. Female tuatara lay eggs only once every four years. When a male wants to mate, he makes his skin darker. He also raises his crests and walks around the female with stiff legs.

It takes a female a long time to get ready to lay eggs. It can take one to three years for the eggs to form inside her. Then, it takes up to seven months for the eggshells to form. After the eggs are laid, the babies hatch 12 to 15 months later. This means tuatara have babies only every two to five years. This is the slowest reproduction rate of any reptile.

Wild tuatara can still have babies when they are about 60 years old. There's a famous male tuatara named Henry at a museum in New Zealand. He became a father at 111 years old!

The temperature of the egg decides if a baby tuatara will be male or female. Warmer eggs usually produce males, and cooler eggs produce females. If an egg is kept at 21 °C (70 °F), it has an equal chance of being male or female. Scientists are worried that if global temperatures keep rising, there might be only male tuatara born in the future.

Protecting Tuatara

The tuatara has been protected by law since 1895. Like many animals in New Zealand, tuatara are in danger. They face threats from losing their homes and from animals brought in by humans, like the Polynesian rat. Tuatara used to be gone from the main islands of New Zealand. Now, they live on 32 offshore islands. In 2005, some tuatara were released into a special fenced area called Zealandia. This was the first time tuatara lived in the wild on New Zealand's North Island in over 200 years.

Before conservation efforts, about a quarter of tuatara groups had disappeared in the last 100 years. Today, there are an estimated 60,000 to 100,000 tuatara in total.

In 2008, a tuatara nest was found at Zealandia. A baby tuatara hatched the next year. This was a big success for bringing tuatara back to the mainland.

Tuatara Breeding Programs

Many zoos and wildlife centers in New Zealand have programs to breed tuatara. The Southland Museum and Art Gallery started the first breeding program in 1986. Hamilton Zoo, Auckland Zoo, and Wellington Zoo also breed tuatara. Their goal is to release these tuatara back into the wild.

One amazing success story happened in 2009. All 11 eggs from Henry (the 110-year-old tuatara) and Mildred (an 80-year-old female) hatched! Henry even had surgery for a tumor before he could have babies.

In 2016, Chester Zoo in England successfully bred tuatara. This was the first time it happened outside of New Zealand.

Tuatara in Culture

Tuatara are very important in Māori culture. They appear in many old stories and are seen as ariki, which means "God forms." Tuatara are also thought to be messengers of Whiro, the god of death. Māori women were traditionally not allowed to eat them.

Tuatara also mark tapu, which are sacred and restricted areas. Crossing these boundaries could have serious results. Today, tuatara are seen as a taonga, a special treasure. They are also guardians of knowledge.

The tuatara was once shown on the New Zealand five-cent coin. This coin was taken out of use in 2006.

Cool Facts About Tuatara

- Even though it looks like a lizard, the tuatara is actually a different kind of reptile. It belongs to its own special group called Sphenodontia.

- The closest living relatives of tuatara are lizards and snakes.

- Like lizards, tuatara can break off their tail if a predator catches them. The tail will grow back, but it takes a long time.

- The ancestors of tuatara were related to dinosaurs and crocodiles.

- Tuatara look very similar to their ancestors from millions of years ago. Because of this, they are sometimes called "living fossils."

- Tuatara have a "third eye" on the top of their head. It's called the parietal eye. You can only see it in baby tuatara. After a few months, it gets covered by scales.

- Tuatara don't have an outer ear or an eardrum. But they can still hear sounds!

- Tuatara can live for a very long time. Many live to be 60 years old, and some in zoos have lived over 100 years. Some experts think they could even live up to 200 years!

- Tuatara protect their homes. They will threaten and bite anyone who tries to enter. Their bite can be serious, and they don't let go easily.

- Tuatara have their own special tick, called the tuatara tick. This tick only lives on tuatara.

Images for kids

-

Tuatara at the Karori Sanctuary have colored marks on their heads to help identify them.

See also

In Spanish: Tuátaras para niños

In Spanish: Tuátaras para niños