Táhirih facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Táhirih Qurrat al-'Ayn

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Fatemeh Baraghani

1814 or 1817 |

| Died | August 16–27, 1852 (aged 35) Ilkhani Garden, Tehran, Persia

|

| Occupation | Poet theologist and women's rights activist |

| Spouse(s) | Mohammad Baraghani (divorced) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parents |

|

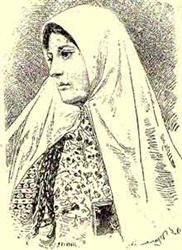

Táhirih (Persian: طاهره, meaning "The Pure One") was also known as Qurrat al-ʿAyn (Arabic: قرة العين, meaning "Solace of the Eyes"). Her birth name was Fatimah Baraghani. She lived from about 1814 or 1817 to 1852. Táhirih was an important poet, a strong supporter of women's rights, and a religious thinker in the Bábí faith in Iran.

She was one of the Letters of the Living. This was the first group of people who followed the Báb. Her life, her influence, and her execution made her a key figure in this religion. Táhirih was born into a very important family. Her father was Muhammad Salih Baraghani. She had a new way of understanding the Bábí faith. This idea connected the Bábí faith with the idea of a special leader who would bring change.

As a young girl, her father taught her at home. She was a very talented writer. When she was a teenager, she married her cousin. This marriage was difficult. In the early 1840s, she became a follower of Shaykh Ahmad. She started writing secret letters to his successor, Kazim Rashti. Táhirih traveled to the holy city of Karbala to meet Kazim Rashti. But he died a few days before she arrived.

In 1844, when she was about 27, she learned about the teachings of the Báb. She believed he was the promised leader, the Qa'im. She quickly became famous for teaching his faith. She was known for her strong belief and "fearless devotion." Later, she was sent back to Iran. Táhirih taught her faith whenever she could. The religious leaders in Persia did not like her. She was arrested several times. Throughout her life, she argued with her family. They wanted her to return to their old beliefs.

Táhirih is best remembered for taking off her veil. She did this in front of a group of men at the Conference of Badasht. This act caused a lot of debate. But the Báb supported her. He gave her the title "the Pure One." The Báb continued to praise Táhirih highly. In one of his writings, he said her importance was equal to all the other seventeen male Letters of the Living combined. She was soon arrested and held in her home in Tehran. In mid-1852, she was secretly executed because of her Bábí faith and her unveiling. Before she died, people believe she said: "You can kill me as soon as you like, but you cannot stop the emancipation of women."

Since her death, Bábí and Baháʼí literature have honored her as a martyr. She is called "the first woman suffrage martyr." She was a very important Bábí. She was the seventeenth follower or "Letter of the Living" of the Báb. Followers of the Baháʼí Faith and Azalis respect her greatly. She is often mentioned in Baháʼí writings as an example of courage in the fight for women's rights. We do not know her exact birth date. Her birth records were destroyed when she was executed.

Contents

Táhirih's Early Life

Táhirih was born Fatemeh Baraghani in Qazvin, Iran. This city is near Tehran. She was the oldest of four daughters. Her father was Muhammad Salih Baraghani. He was a religious scholar. He was known for explaining the Quran. He also spoke about the sad events of Karbala. Her mother came from a noble Persian family. Her mother's brother was a religious leader in Qazvin.

Táhirih and her sisters studied at the Salehiyya school. Her father had started this school in 1817. It had a section for women. Táhirih's uncle, Mohammad Taqi Baraghani, was also a powerful religious leader. He had a lot of influence in the Shah's court. Historians are not sure of her exact birth date. Some say 1817, others 1814 or 1815.

The Baraghani brothers moved from a small village to Qazvin. They became rich and powerful through religious schools. They became high-ranking religious leaders in the Shah's court. They also ran religious parts of Qazvin. The brothers were also involved in trade. They gained great wealth and royal favor. Her family was one of the most respected and powerful in Persia when she was born.

Her Education

Táhirih received a very good education for a girl of her time. It was rare for women to be able to read and write. Her father decided to teach his daughter himself. Táhirih grew up in a strict religious home. But she studied religion, law, Persian literature, and poetry. She was allowed to study Islamic teachings. She was known for being able to memorize the Qurʼan. She also understood difficult religious laws.

Her father was said to wish she had been a son. Táhirih was better than her father's male students. This made him even more sure of her writing talents. Her father even let her listen to his lessons for male students. She had to hide behind a curtain so no one knew she was there. Her father lovingly called her "Zarrín Táj," which means "Crown of Gold."

Táhirih's education helped her understand religious matters better than others. Girls were expected to be quiet and shy. Many parents did not want their daughters to get an education. Her father was a writer. He wrote about the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali. He also wrote about Persian literature. He spent a lot of time studying.

Táhirih was known for her charm and beauty. People who met her often praised her. A court official called her "moonfaced" with "hair like musk." One of her father's students wondered how such a beautiful woman could be so smart. Historian Nabíl-i-Aʻzam wrote about her "highest terms of beauty." British Professor Edward Granville Browne said she was famous for her "marvellous beauty." Her education made her very religious. She kept these beliefs throughout her life. It also made her eager for knowledge. She spent her time reading and writing religious and other books. Her formal education ended when she was about thirteen or fourteen. Her father and uncle arranged for her to get married.

Marriage and New Ideas

Táhirih was a talented writer and poet. But she had to follow her family's wishes. At age fourteen, she married her cousin, Muhammad Baraghani. He was her uncle's son. They had three children: two sons, Ibrahim and Ismaʻil, and one daughter. But the marriage was unhappy from the start. Muhammad Baraghani did not seem to want his wife to continue her studies.

In Qazvin, Táhirih was known for her beauty and knowledge. However, knowledge was not seen as a good quality for a daughter or wife. Her husband later became a leader of the Friday prayers. Her two sons left their father after their mother died. They went to Najaf and Tehran. Her daughter died soon after her mother. It was in her cousin's home that Táhirih first learned about the Shaykhi movement. She started writing letters to its leaders, including Kazim Rashti. This movement was strong in the holy cities of Iraq.

Táhirih found the new Shaykhi teachings in her cousin's library. At first, her cousin did not want her to read the books. He said her father and uncle were against the movement. But Táhirih was very interested. She wrote often to Siyyid Kazim, asking him religious questions. Siyyid Kazim was happy with her devotion. He was pleased to have another supporter from the powerful Baraghani family. He wrote to her, calling her his "Solace of the Eyes" and "the soul of my heart."

At first, Táhirih kept her new religious beliefs secret. But with her new faith, it was hard for her to follow her family's strict religious rules. She began to argue openly with them. The religious tension led Táhirih to ask her father, uncle, and husband to let her go on a pilgrimage to Karbala. In 1843, at about 26, Táhirih left her husband. She went to Karbala with her sister. Her real reason for the trip was to meet her teacher, Kazim Rashti. But he had died by the time she arrived. With his widow's permission, she stayed in Siyyid Kazim's house. She continued teaching his followers from behind a curtain.

In Karbala, Táhirih taught Kazim Rashti's students. His widow let her read many of his unpublished works. Táhirih also became friends with other women in his household. She had to teach from behind a curtain. It was not proper for a woman's face to be seen in public. It was also not suitable for a woman to be with men, let alone teach them. This caused a lot of debate in Karbala. Still, she gained many followers, including many women. Her teaching was not liked by the male religious leaders. Other male Shaykhis made her move to Kadhimiya for a short time.

Her Conversion

In 1844, Táhirih learned about and accepted ʻAli Muhammad of Shiraz. He was known as the Báb. She believed he was the Mahdi, a promised leader. She became the seventeenth follower, or "The Letter of the Living," of the Báb. She quickly became known as one of his most famous followers. Táhirih asked her sister's husband to send the Báb a message. She wrote a poem expressing her belief in him.

Táhirih was the only woman in this first group of followers. She is often compared to Mary Magdalene. Unlike the other Letters of the Living, Táhirih never met the Báb. She continued to live in Siyyid Kazim's home. She began to spread the new religion of the Báb, Bábism. She attracted many Shaykhis in Karbala.

Táhirih as a Bábí Follower

While in Karbala in Iraq, Táhirih continued to teach her new faith. Some religious leaders complained. So, the government moved her to Baghdad. She stayed at the home of the mufti of Baghdad, Shaykh Mahmud Alusi. He was impressed by her devotion and intelligence. Táhirih was attacked with stones as she left for Baghdad.

In Baghdad, she started teaching the new faith publicly. She challenged and debated with the religious leaders. Táhirih's behavior was seen as improper for a woman. This was especially true because of her family background. She was not well-received by the clergy. Despite this, many women admired her lessons. She gained a large number of women followers.

At some point, the authorities in Baghdad argued that Táhirih was Persian. They said she should argue her case in Iran. In 1847, the Ottoman authorities sent her to the Persian border. She was deported with other Bábís. One reason might have been her new religious ideas. The Báb at first said his followers should follow Islamic law. But his claim as the Báb, a direct authority from God, could conflict with this. Táhirih seemed to understand this. She connected the Báb's authority with ideas from Shaykhism. Táhirih seemed to make this connection before the Báb himself. But she soon received letters supporting her ideas.

American Martha Root wrote about Táhirih. She described her as one of the most beautiful young women in Iran. She was a genius, a poet, and a very learned scholar. She was the daughter of a family of religious scholars. Her father was a high priest. She was very rich and lived in a beautiful palace. She was known for her great courage. Martha Root asked readers to imagine what it meant for such a young woman to become the first woman follower of the Báb.

Her Poetry

After she became a Bábí, Táhirih's poems became very popular. In most of them, she wrote about her wish to meet the Báb. Her poetry shows her impressive knowledge of Persian and Arabic literature. This was rare for a woman in Iran in the mid-1800s. One of her most famous poems is called Point by Point. Many consider it her best work.

When Táhirih was killed, family members who were against her destroyed or hid her remaining poems. Her other poems were spread across Iran. It is thought that Táhirih was not very interested in printing her poems. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá remembered that when he was five, Táhirih would sing her poetry to him in her beautiful voice. Edward Granville Browne collected her poems from Bábí, Baháʼí, and Azali sources. He published them in his book A Year Amongst the Persians.

Later, scholars John S. Hatcher and Amrollah Hemmat collected and translated her poems. They published a book called The Poetry of Táhirih (2002). They also found two handwritten copies of her poems. These were previously unpublished and unknown. This led to two more books by Hatcher and Hemmat. These books included English translations and copies of the original writings. The first book, Adam's Wish (2008), has a long poem about Adam and other prophets. It describes their wish to see humanity grow up. The second book, The Quickening, was published in 2011. It also includes copies of the original writings. Some scholars wonder if all the poems in the writings are by Táhirih.

Return to Iran

During her trip back to Qazvin, she openly taught the Bábí faith. She stopped in places like Kirand and Kermanshah. There, she debated with the main religious leader, Aqa ʻAbdu'llah-i-Bihbihani. He wrote to Táhirih's father. He asked her relatives to remove her from Kermanshah. She then traveled to Sahneh and then to Hamadan. There, she met her brothers. They had been sent to ask her to return to Qazvin. She agreed to go back with her brothers. But first, she made a public statement in Hamedan about the Báb. Her father and uncle were very upset by Táhirih's behavior. They felt it brought shame to the Baraghani family. When she returned to Qazvin in July 1847, she refused to live with her husband. She saw him as not believing in her faith. Instead, she stayed with her brother.

In Qazvin and Escape to Tehran

After she arrived at her family home, her uncle and father tried to make her leave the Bábí faith. But Táhirih argued and showed religious "proofs" for the Báb's claims. A few weeks later, her husband quickly divorced her. Her uncle, Muhammad Taqi Baraghani, began to speak against his niece publicly. This caused a lot of controversy in Qazvin. It further damaged the Baraghani family's reputation.

Rumors spread in the court about Táhirih's bad behavior. But these were likely made up to harm her reputation. A Qajar writer said he was amazed by her beauty. He described her "body like a peacock of Paradise." He also wrote that she had nine husbands (later changed to ninety). He also wrote that she acted improperly with "wandering Bábís."

These rumors hurt the Baraghani family's reputation. Táhirih wrote a letter to her father saying they were lies. She mentioned "slanderous defamation" and denied "worldly love." Her father was reportedly convinced that his daughter was pure. He remained devoted to her memory. After the criticism from the religious leaders in Qazvin, he moved to Karbala. He died there in 1866. Her father may not have believed the rumors. But her uncle, Mulla Muhammad Taqi Baraghani, was horrified. He blamed the Báb for bringing shame to his family.

While she was in Qazvin, her uncle, Mulla Muhammad Taqi Baraghani, was murdered. He was a religious leader known for being against the Shaykhi and Bábí movements. A young Shaykhi killed him. Táhirih's husband blamed her for this, even though she said she was not involved. During Táhirih's stay in Qazvin, Baraghani had given sermons attacking the Báb and his followers. There is no clear proof of who the killer was. There is also no proof of Táhirih's involvement.

When she was arrested, Táhirih's powerful father convinced the authorities not to kill her. Instead, she was imprisoned in her home. Táhirih's father kept her under house arrest in his cellar. He had her maids act as spies. Some family members said this was done out of real fear for her safety. Her father believed his daughter was innocent. But her husband was strongly against her. He argued that Táhirih should be tried for her uncle's murder. Her father refused, saying Táhirih would never leave her home. Still, authorities arrested Táhirih and one of her maids. They hoped the maid would give evidence against her.

In her trial, Táhirih was questioned for hours about her uncle's murder. She denied any involvement. To pressure her, Táhirih was threatened. Her maid was almost tortured to get evidence from Táhirih. But this failed after the murderer himself confessed. Táhirih returned to her father's home. She was still a prisoner and watched closely.

This accusation put her life in danger. With help from Baháʼu'lláh, she escaped to Tehran. Táhirih stayed at Baháʼu'lláh's home. She was in the private room of his wife, Ásíyih Khánum. Ásíyih personally took care of Táhirih while she was hiding. It was there that she first met ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. She became very fond of the boy, who was about three or four years old. Táhirih asked Baháʼu'lláh if she could go to Māku. She wanted to see the Báb, who was a prisoner there. But Baháʼu'lláh explained that the journey was impossible.

Conference of Badasht

In June–July 1848, several Bábí leaders met in Badasht. This meeting was partly organized and paid for by Baháʼu'lláh. It marked the public beginning of the Bábí movement.

One reason for the meeting was to make a complete break from the Islamic past for the Bábí community. Another goal was to find a way to free the Báb from prison. Táhirih strongly pushed for an armed rebellion to save the Báb and create this break. It seems that much of what Táhirih wanted was more than most other Bábís were ready to accept.

Bábís were somewhat divided. Some, like Táhirih, saw the movement as a break from Islam. Others, like Quddus, wanted a more careful approach. As a symbolic act, Táhirih took off her traditional veil. She did this in front of a group of men. On another occasion, she held a sword. The unveiling shocked the men present. Before this, many saw Táhirih as very pure. They saw her as a spiritual return of Fatimah, the daughter of the prophet Muhammad. Many screamed in horror. One man was so shocked that he cut his own throat. With blood pouring, he ran away.

Táhirih then stood up and spoke about breaking away from Islam. She quoted from the Quran. She also said she was the "Word" that the Qa'im would speak on the "day of judgment." The unveiling caused great debate. Some Bábís even left their new faith.

Bábís and Baháʼís see the Conference of Badasht as a key moment. It showed that Islamic law had been replaced by Bábí law. However, the unveiling led to accusations of bad behavior by Muslim religious leaders. The Báb supported Táhirih's actions. He approved the name Baháʼu'lláh gave her at the conference: the Pure (Táhirih). A jailer who knew her praised her character. Modern women scholars see these accusations as typical for women leaders and writers of that time.

Imprisonment and Death

After the Badasht conference, Táhirih and Quddus traveled to Mazandaran province. They then separated. They often faced problems on their journey. Some reports say this was because they stayed in the same inns and used the same public bath. Other reports say anti-Bábí villagers bothered them. Finally, when they arrived in Barfurush, Bábís gave them shelter.

Nearby villagers attacked the Bábís. Táhirih was captured during this time. She was put under house arrest in Tehran. She stayed at the home of Mahmud Khan, the mayor. While there, she earned respect from women around Tehran. They came to see her. Even Mahmud Khan himself respected her. Táhirih seemed to gain the respect of Mahmud Khan and his family. This was also the first time she was mentioned in Western newspapers.

Meeting the King

After her capture and arrest, Táhirih was taken to Tehran. In Tehran, Táhirih was brought before the young king, Nasser-al-Din Shah. He reportedly said, "I like her looks, leave her, and let her be." She was then taken to the home of the chief, Mahmud Khan. The Shah then wrote her a letter. He told her she should deny the teachings of the Báb. If she did, she would be given an important position in his royal household. Táhirih refused his offer. She wrote a poem in response. The Shah was reportedly pleased by her intelligence. Despite the King's request for her to be left alone, she was placed under house arrest. The day before she was killed, she was again brought before the King. He questioned her again about her beliefs. Táhirih remained a prisoner for four years.

Her Final Days

Even as a prisoner, Táhirih had some freedom. She still taught her religion to people in the mayor's house. She openly spoke against having many wives, wearing the veil, and other limits on women. Her words soon made her an important person. Women came in large numbers to see Táhirih. One princess from the Qajar family even became a Bábí.

However, the religious leaders and court members feared she had become too influential. They held seven meetings with Táhirih. They wanted to convince her to give up her faith in the Báb. Instead, Táhirih presented religious "proofs" for the Báb's cause. At the last meeting, she cried out, "When will you lift your eyes toward the Sun of Truth?" Her actions shocked the group. They were seen as improper for a woman, especially one from her background.

After the last meeting, the group returned. They began writing an order saying Táhirih was a heretic. This meant she should be sentenced to death. Táhirih was the first Iranian woman to be executed for "corruption on earth." This charge is still used today. Táhirih was then confined to one room in the mayor's house. She spent her last days praying, meditating, and fasting. "Do not weep," she told the mayor's wife. "The hour when I shall be killed is coming soon."

Her Execution

Two years after the execution of the Báb, three Bábís tried to kill Nasser-al-Din Shah. They did this on their own. The attempt failed. But it led to new persecution of the Bábís. Táhirih was blamed because of her Bábí faith. When she was told about her execution, Táhirih kissed the messenger's hands. She dressed in bridal clothes. She put on perfume and said her prayers. She made one request to Mahmud Khan's wife: to be left in peace to continue her prayers. Mahmud Khan's young son went with Táhirih to the garden.

In the middle of the night, Táhirih was secretly taken to the nearby Ilkhani garden in Tehran. She was killed there. One of her most famous quotes is her last words: "You can kill me as soon as you like, but you cannot stop the emancipation of women." She was about 35 years old and left behind three children. Dr. Jakob Eduard Polak, the Shah's doctor, saw the execution. He described it: "I saw the execution of Qurret el ayn. The war minister and his assistants killed her. The beautiful woman faced her death with amazing strength." ʻAbdu'l-Bahá praised Táhirih. He wrote that she was a "woman pure and holy, a sign of amazing beauty, a burning fire of the love of God." The Times newspaper reported Táhirih's death on October 13, 1852. It called her the "Fair Prophetess of Kazoeen" and the "Bab's Lieutenant."

Táhirih's Legacy

Táhirih is seen as one of the most important women in the Bábí religion. She was a key figure in its growth. She was a very inspiring person. She was able to go beyond the limits placed on women in her traditional society. This brought attention to the Bábí Cause. She wrote many works on Bábí topics. About a dozen important works and a dozen personal letters have survived. Around 50 poems are said to be hers. They are highly valued in Persian culture.

Táhirih is well-known among Baháʼís. They see her as one of the leading women in their religion. Her influence has also spread beyond the Baháʼí community. Her life has inspired later generations of feminists. Azer Jafarov, a professor in Azerbaijan, said that she influenced modern literature. She called for women's freedom. She had a deep impact on public awareness.

One of the earliest Western accounts of Táhirih was on January 2, 1913. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, the head of the Baháʼí Faith, spoke about women's suffrage to the Women's Freedom League. He mentioned Táhirih in his speech.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Táhirih para niños

In Spanish: Táhirih para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |