United States war plans (1945–1950) facts for kids

The United States made and changed plans for a possible war with the Soviet Union (USSR) between 1945 and 1950. Even though many plans were not practical, they would have been used if a conflict had started. It was not thought that either country wanted war. However, they believed a war could happen by accident. Military leaders from the US, United Kingdom, and Canada worked together on these plans.

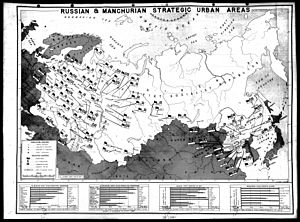

US military experts believed the Soviet Union could gather a huge army. They thought the Soviets could send 120 divisions to Western Europe, 85 to the Middle East, and 40 to Asia. All war plans expected the Soviets to attack first. Defending Western Europe seemed very hard. Plans like Pincher, Broiler, and Halfmoon suggested falling back to the Pyrenees mountains. Meanwhile, air attacks would launch from bases in the UK, Okinawa, and the Middle East. Ground forces would then attack southern Russia from the Middle East. By 1949, the Offtackle plan aimed to stop Soviet forces at the Rhine river. If that failed, they would retreat to the Pyrenees. Another idea was to invade Soviet-controlled Western Europe from North Africa or the UK, similar to Operation Overlord in World War II.

Even with doubts about how well they would work, air attacks were seen as the only way to strike back quickly. These air attack plans grew bigger over time. They included dropping up to 292 atomic bombs and a huge amount of regular bombs. Experts thought 85% of Soviet factories would be destroyed. This included power plants, shipyards, and oil production. About 6.7 million people were expected to be hurt or killed. The United States Air Force and the United States Navy argued about whether the Navy should help with strategic bombing. They also argued if it was a good use of resources. The idea of using nuclear weapons to stop an attack (called nuclear deterrence) was not part of these early plans.

Contents

Why Plan for War?

In 1944, during World War II, US military leaders predicted that the US and the Soviet Union would become the world's top powers. Britain was still important, but its power was much less. In February 1945, the US military thought about what the Soviet Union would do after the war. They expected the Soviets to reduce their army to rebuild their economy, which was badly damaged. They thought the Soviet economy would not recover before 1952. Until then, the Soviet Union would try to avoid war. But for its own safety, it would try to control countries near its borders. Even after reducing its army, the Soviet Union would still be very strong. US intelligence reports guessed they would keep over 4 million troops and 113 military divisions. Another 84 divisions would come from countries allied with the Soviets.

During World War II, the US gathered the largest military in its history. The United States Army (which included the Army Air Forces then) had 8.3 million members. The United States Navy and United States Marine Corps had 3.8 million. By early 1945, plans were made to move 21 divisions (about 1 million people) from Europe to the Pacific for the invasion of Japan. About 400,000 people would stay in Europe to help occupy Germany. The Army would let 2 million people leave active duty based on a points system. Soldiers earned points for how long they served, how long they were overseas, if they had children, and for awards. Those with the most points could leave first.

When Japan surrendered in August 1945, 581,000 Army members had already left. Due to strong public and political pressure, the US military reduced its size much faster than planned. By June 1946, the Army had only 1.4 million members. The Navy had 983,000, and the Marine Corps had 155,000. By June 1947, the Army was down to 990,000, the Navy to 477,000, and the Marine Corps to 82,000. Only one US division remained in Europe. Meanwhile, European countries were still recovering from the war. They could not afford to keep large armies.

Over the next few years, several war plans were made for a possible conflict with the Soviet Union. Military planners talked with Vannevar Bush, who led a committee on new weapons, and Leslie R. Groves, who directed the Manhattan Project. They discussed new weapons like nuclear weapons and long-range missiles. Bush doubted that a missile like Germany's V-2 rocket, but with a range of 2,000 miles, could be built. Even if it could, it would need Allied bases overseas to reach the Soviet Union. Groves was more hopeful. He agreed that long-range missiles were not possible in 1945, but thought they might be in 10 to 20 years. For atomic bombs, he suggested building up a supply. However, he warned that destroying a country's factories would not decide the war's outcome.

The Pincher Plan (1946)

On March 2, 1946, military planners shared an early war plan called Pincher. This plan, updated in April and June, guessed that the Soviets could send 270 divisions to Europe, 42 to the Middle East, and 49 to Asia within 60 days of starting to prepare for war. The Middle East was seen as the most likely place for fighting to begin. This is because Soviet goals might clash with Britain's goals there. The US would try to stay neutral at first, but might get pulled in, like in 1917 and 1941.

The plan thought the Soviet Union could quickly take over Europe east of the Rhine river. The Rhine was a big obstacle, but it was expected to fall quickly. This would force US and British forces to retreat to the Pyrenees mountains. Planners believed that Italy, Spain, Denmark, and Scandinavia could be defended against larger forces. However, they expected British and French forces to focus on defending their own countries. They would not want to send troops to Scandinavia, but might help defend Spain and Italy. The Soviet push into Western Europe would likely happen at the same time as a push into the Middle East. If the Soviets also attacked in Asia, US forces would fall back to Japan.

The US military's goal would be to hold the British Isles, North Africa, India, China, and Japan. From these places, air attacks could be launched. The Navy would also block Soviet ports. The idea of a second Operation Overlord (a large invasion) was rejected. This would mean fighting the Soviets where they were strongest, far from their home. Taking back Scandinavia was considered, but it would be very difficult to supply troops there. So, the preferred plan was to attack the Dardanelles and Bosporus straits, and invade the Soviet Union through the Black Sea. The plan did not specifically say to use nuclear weapons. But it noted that there were no bases close enough for Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers to reach key targets. The B-29 was the most advanced long-range bomber the US had at the time. The plan did not include what would happen after the first counter-attack. It also did not explore how hard it would be to supply a large force in the Middle East. Still, on July 8, 1946, military leaders accepted Pincher as the basis for future planning.

Based on Pincher, studies were done for different regions. The first was Broadview, about defending North America. It was released in August 1946. Long-range weapons meant the US homeland was no longer safe. The Soviet Union could launch one-way air strikes and commando raids. Submarines could attack ships and lay mines in American waters. But the biggest threat was seen as sabotage by Soviet agents. After 1950, there was a chance the Soviet Union would get nuclear weapons and long-range aircraft or missiles to attack US cities. An invasion of Alaska was also considered. To fight these threats, the US would need mobile ground forces, an air warning system, and anti-submarine forces.

Plan Griddle, released in August 1946, focused on defending Turkey. The Turkish Army was large but lacked modern equipment. The study estimated the Soviet Union could send up to 110 divisions against Turkey. They imagined a two-part attack: one on Eastern Thrace from Soviet-allied Bulgaria, and another into Anatolia from Soviet Transcaucasia. Airborne and amphibious forces could attack both sides of the Dardanelles and Bosporus. From Turkey, Soviet forces could move into Iraq and Iran. It was thought Turkey could hold out for at most 120 days before its forces had to retreat. Still, Turkey was important to US strategy as a possible base for air attacks on the Soviet Union. It could also help stop the Soviet push into the Middle East. So, the study called for more military aid to Turkey and better airbases and ports there.

This led to the Caldron study, released in November 1946, which looked at the Middle East. While the Soviet Union had enough oil for its normal needs, planners thought it did not have enough for a major war. So, taking the Middle East's oil would be a Soviet priority. This would also keep the oil from the Allies. The region was also seen as an important place to launch an attack on the Soviet Union. So, it was expected the Soviets would try to prevent that. Up to 85 Soviet divisions would be available for operations in the Middle East. The British would have only five divisions to stop them. Soviet forces were expected to reach Palestine within 60 days. About 14 Allied divisions could gather in Egypt.

Cockspur, a study on the threat to Italy, was dated December 20, 1946. It imagined an attack on Italy by Yugoslav forces while Soviet forces focused on taking over Germany. Once Germany was taken, Soviet forces could then invade Italy from the north. The Allies could try to defend northern Italy, which seemed impractical, or make a fighting retreat. This raised the chance of Allied forces being defeated, leaving nothing to defend Sicily. So, the study suggested the best plan was to retreat to Sicily right away.

Since the Pincher plan called for a retreat to the Pyrenees, the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) became very important. Drumbeat, released in August 1947, dealt with its defense. It was estimated that Spain could gather 22 divisions in 60 days, but the Spanish Army was considered only fair in quality. Portugal could gather two more divisions. There were also 5,000 British troops in Gibraltar. Planners did not think the Soviet Union would attack Spain, but they considered the possibility. They estimated that up to 20 Soviet divisions could reach the Pyrenees by 45 days after a war started, and 50 divisions by 90 days. Still, planners thought there was a chance the Allies could hold Spain.

The Far East was considered less important. Plan Moonrise, which covered it, was presented in August 1947. It estimated the Soviet Union could send about 45 divisions to the region. Given the limited power of the Soviet Pacific Fleet, the Soviet Union's main target would be China. The Nationalist Chinese Army was large but mostly ineffective. Soviet forces would be helped by 1.1 million Chinese Red Army troops and 2 million militia, and perhaps three divisions from Mongolia, a Soviet-allied state. The first part of a Soviet attack was expected to target the Port Arthur area. Manchuria would soon be taken, and Beijing would fall in about 10 days. Planners estimated Soviet forces could reach the Yellow River by 90 days after a war started, and Nanjing and Hankou in another three weeks. An advance to the Yangtze River was not expected. At the time, US forces were still in Korea, but the plan called for them to withdraw to Japan.

The Broiler Plan (1947)

Even though the Pincher studies were not fully accepted as a war plan, by July 1947, enough progress had been made to create one. In August, military planners were told to develop a new plan based on Pincher. This plan, called Broiler, assumed a war would start in 1948. It also assumed the US would be allied with Britain and Canada, and that atomic weapons would be used. The greater focus on atomic weapons was a big change.

Broiler started with estimates of how strong the US forces were. The same scenario as Pincher was imagined. Military intelligence still thought the Soviet Union was very strong. It could gather 245 divisions, with 120 in Western Europe, 85 in the Balkans and Middle East, and 40 in the Far East. This meant it could take over most of Europe in 45 days. In the long run, the Soviet Union was expected to have not just more troops, but also equally advanced technology. It was thought the Soviet Union would have nuclear weapons by 1952, and long-range bombers to deliver them to US targets by 1956.

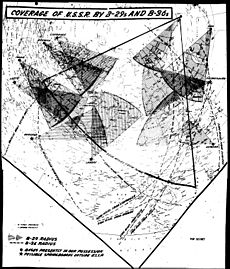

To protect the United States, Greenland and Iceland would be occupied. New ways to refuel planes in the air would let B-29 and B-50 bombers (an improved B-29) attack 20 major Soviet cities. B-29s were turned into refueling planes, but the first ones were not ready until late 1948. Major overseas bases would be set up in the UK, Okinawa, and Karachi. The Cairo-Suez and Basra areas were rejected because they could not be defended. Planners admitted Karachi was not ideal, but at least it could be defended.

The US plan for gathering its forces, submitted in February 1947, assumed nuclear weapons would not be used. It called for an Army of 13 divisions at the start of a war, growing to 45 divisions in one year, and 80 divisions in two years. This was similar to what happened in World War II. In July, a new plan was submitted that included using nuclear weapons. Assuming 100 to 200 nuclear weapons would be ready, it called for 34 atomic bombs to be dropped on 24 Soviet cities. Seven would hit Moscow, three Leningrad, and two each on Kharkov and Stalingrad. This was expected to cause huge damage to Soviet industries and kill or injure about one million people. The damage might make the Soviet Union ask for peace.

However, the idea that 100 atomic bombs were available was wrong. The exact number of bombs was a big secret in 1947. President Harry S. Truman was surprised when he learned how few bombs the US actually had. By June 1948, there were parts for about 50 Fat Man bombs and two Little Boy bombs. These were not ready bombs. They were parts that had to be put together by special teams. A well-trained team could assemble a bomb in two days. But the teams that had built bombs during the war had gone back to civilian life. The first US Army unit for this was formed in August 1947. Bomb parts would need to be flown to these teams at bases closer to the enemy.

In 1948, the United States Navy started training its own special weapons unit. The Navy planned to deliver Little Boy nuclear weapons from its aircraft carriers using certain bombers. The Air Force slowly became the main branch for delivering nuclear weapons. By the end of 1949, it had 12 special units. The Navy's desire to be part of strategic bombing caused arguments with the Air Force.

Only special B-29 bombers could carry Fat Man nuclear weapons. Of the 65 such B-29s made, only 32 were ready for use in early 1948. All of them were assigned to a special bombing group in New Mexico. Trained crews were also scarce. At the start of 1948, only six crews were ready for atomic bombing missions. Up to 20% of the target cities were too far for the B-29 to reach and return. This would mean a one-way mission, losing the crew, bomb, and plane. The Convair B-36 Peacemaker, with a longer range, was being introduced in 1948, but it could not carry atomic bombs yet. There were also doubts if the B-29 could fly into Soviet airspace. As a propeller plane, it was no match for Soviet jet fighters, even at night.

The need to rely on nuclear weapons changed military thinking. During World War II, the US Army Air Forces had destroyed enemy cities. But they had always said they aimed for "precision bombing" (hitting specific targets). Now, "area bombing" (hitting a whole city area) became the official plan. One reason for this was that the US did not know the exact locations of Soviet factories. They hoped that with the power of atomic bombs, just hitting the right cities would be enough.

However, this was not certain. In January 1949, Lieutenant General Curtis LeMay, who led the Strategic Air Command (SAC), ordered a practice attack on an air base. A similar exercise in May 1947 had shown problems. This time, crews were told to attack at high altitude and at night, using radar. They were given old maps of an Ohio city, which were still better than their maps of the Soviet Union. The high altitude and cold weather caused problems for planes and crews. Many missions were canceled due to freezing rain. Radar had trouble finding targets because of ground clutter and thunderstorms. Of 303 practice attacks, two-thirds missed the target by more than 7,000 feet. The average miss was 10,000 feet. The atomic bombs of that time would have missed their targets completely.

When military logistics experts studied the plan, they found huge needs for ships. Supporting forces in the Cairo-Suez area would need 912 ships after six months. If the Mediterranean Sea was closed, the longer route around Africa would need 1,042 ships. Over two years, the need would rise to 2,252 and 3,848 ships. It would take 16 months to get so many stored cargo ships ready. Allied forces would need 32,360 tons of supplies per day. But the ports in the Red Sea could only handle 26,400 tons.

An October 1947 assessment of aircraft needed for the first year was 91,332 planes of all types. But a month later, the Munitions Board said this was not realistic. The logistics experts also found the plan for gathering manpower unrealistic. It would need 300,000 men inducted per month, which would strain training and supply systems. In January 1948, the Munitions Board reported that the Broiler plan needed resources that were not available. It was estimated that storing equipment and getting factories ready would cost $139.6 million in 1949, but only $37.6 million was available. They suggested a more realistic war plan.

Broiler was presented to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in March 1948. A slightly changed version, called Frolic, was sent to Secretary of Defense James Forrestal. Although Broiler was accepted as an emergency plan, all the Joint Chiefs had doubts. Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy did not like relying on nuclear weapons when it was not certain they would be allowed. Admiral Louis E. Denfeld, the Chief of Naval Operations, disagreed with giving up Western Europe. He argued this went against US foreign policy. He believed a better strategy would be to build up US forces in Europe to hold the Rhine.

The Halfmoon Plan (1948)

By 1948, the US was deeply involved in world politics. At the same time, strict limits on defense spending created a growing gap between what the military had and what it needed to do. Western Europe was still weak and divided. China was in a civil war. Planners from the US, Britain, and Canada met in Washington, D.C., in April 1948. They created an emergency war plan based on Broiler, called Halfmoon (later renamed Fleetwood in August 1948).

More countries were assumed to be on the Allied side. This included the British Commonwealth, the Western Union countries (France, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg), and all of the Western Hemisphere. Turkey, Spain, Norway, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen would become allies if attacked by the Soviet Union. Britain insisted that the Cairo-Suez area could be held, so a base there was added instead of Karachi. However, the Americans kept Karachi as a backup. Air attacks would be launched with B-36 bombers from the US and B-29 and B-50 bombers from the UK, Cairo-Suez, and Okinawa.

Halfmoon assumed atomic bombs would be used by the US from the start. It also assumed the Soviet Union would use them once they developed them. US intelligence incorrectly thought this would not happen until 1949. Without enough regular forces, planners felt they had no other choice. President Harry S. Truman was told about Halfmoon in May 1948, and he had doubts. He asked for a plan to "resist a Russian attack without using atomic bombs." He worried they might not have enough bombs, or that people might not allow their use for attacking.

Secretary of the Army Kenneth C. Royall was especially worried by Truman's objection. He called for a review of the national policy on using nuclear weapons. He brought it up at a meeting where Secretary of State George C. Marshall said Truman's policy of resisting the Soviet Union without the means to do so was "playing with fire." In July, Forrestal told the Joint Chiefs to ignore the President's request for an alternative plan. The policy Royall asked for was written by the Air Force and adopted in September. It stated that:

12. It is recognized that, in the event of hostilities, the National Military Establishment must be ready to utilize, promptly and effectively all appropriate means available, including atomic weapons, in the interests of national security and must therefore plan accordingly.

13. The decision as to the employment of atomic weapons in the event of war is to be made by the Chief Executive when he considers such decision to be required.

So, after three years, using nuclear weapons in war plans was officially allowed. While the president still had the final say on their use, planners decided where and when they would be used. An updated Halfmoon plan, called Trojan, was released in January 1949. It included details for air attacks. This plan would target 70 Soviet cities with 133 nuclear weapons. Eight would hit Moscow and seven Leningrad. The main change from Fleetwood was adding Greece, Italy, Iceland, Ireland, the Philippines, and Switzerland to the list of allies. But Arab countries were removed due to worsening relations after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and the creation of Israel.

Military logistics experts used Halfmoon to create a new plan called Cogwheel. This plan detailed what was needed for the first two years of a war, assuming it started on July 1, 1949. The only disagreement among the three military branches was about building more aircraft carriers. The Army and Air Force thought the Navy had enough, and new ones could not be finished in two years. This plan was submitted in September 1948. In December, the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered the three branches to prepare updated plans. Before this could happen, the Munitions Board reviewed Cogwheel. It found that aircraft production would be only 60% of what was needed by the end of the first year. Also, demand for raw materials like copper and aluminum would be more than the supply. The need for weapons would be more than factories could produce. And the demand for manpower was more than the system could handle. So, the Munitions Board decided to plan based on only 50% of Cogwheel's needs.

| Force | At start | After one year | After two years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Army divisions | 20 | 40 | 80 |

| Air Force groups | 66 | 103 | 186 |

| Navy warships | 510 | 1,785 | 2,976 |

| Navy aircraft carriers | 11 | 16 | 25 |

In October 1948, Admiral Denfeld told the Senate Armed Services Committee:

The unpleasant fact remains that the Navy has honest and sincere misgivings as to the ability of the Air Force successfully to deliver the [atomic] weapon by means of unescorted missions flown by present-day bombers, deep into enemy territory in the face of strong Soviet air defenses, and to drop it on targets whose locations are not accurately known.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff approved Trojan in January 1949, but knew it was not a plan that could actually be carried out. General Omar N. Bradley, the Chief of Staff of the US Army, admitted the Army had serious shortages of both people and equipment. They could not fix these problems due to budget limits. Similarly, Denfeld reported the Navy did not have the resources for its part. General Hoyt Vandenberg, Chief of Staff of the Air Force, said the Air Force did not have the means to carry out Trojan. The Joint Chiefs of Staff estimated they needed $29 billion for 1950, but the government would only provide $17 to $18 billion.

The Offtackle Plan (1949)

In February 1949, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower gave new instructions to the planners. He agreed the Rhine could not be held with current forces. But he wanted a plan to return to Western Europe as soon as possible. Over the next seven months, a new plan called Offtackle was created. This was followed by more meetings with British and Canadian representatives. For the first time, some political guidance was available. It stated that the US would not start a war with the Soviet Union. But a conflict could happen if the Soviet Union misjudged American determination. This confirmed an idea already in the war plans since Pincher. It also told the Joint Chiefs that if war happened, the US would not need to force an "unconditional surrender" or occupy the Soviet Union. Like earlier plans, Offtackle only dealt with the start of the war, not how it would end or what would happen afterward.

The air attack plan in Offtackle was even more ambitious than Trojan. It called for dropping 292 atomic bombs and a huge amount of regular bombs. It was estimated that 85% of Soviet factories would be completely destroyed. This included electric power, shipbuilding, and oil production. It was hoped that these attacks would not only cripple Soviet industry but also weaken the government's control, lower people's will to fight, disrupt their war preparations, and slow down Soviet ground forces moving into Western Europe. However, the Strategic Air Command (SAC) did not have the resources to carry out the plan. With its available planes, it could only fly 2,000 missions in the first two months, far short of the 6,000 needed. Supporting them would require 360 transport plane missions, but only 260 were given to SAC. Spare parts for the B-50 bombers were scarce, and there was not enough aviation fuel in reserve.

The first steps to create an alliance for defense in Western countries came with the formation of the Western European Union in March 1948. This was a defense agreement between the UK, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. This was followed by the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in April 1949. In October 1949, Truman signed a law providing $1 billion for NATO allies to buy weapons and equipment. The American ground forces had one division and three regiments in Europe, and five divisions in the US. The entire NATO alliance could field ten divisions in West Germany. But it was estimated that at least 18 divisions were needed to stop a Soviet advance on the Rhine. Despite doubts, in December 1949, the 12 NATO allies accepted a common defense plan.

To follow Eisenhower's instructions, planners considered other options. The main ones were to retreat to the Pyrenees and hold there, or to launch an invasion of Soviet-occupied Western Europe from North Africa or the UK. They did not have enough forces for the first option, so the second strategy was chosen. Field Marshal Lord Montgomery, a British military leader, reported in June 1950 that NATO forces were not able to hold the Rhine. He felt there would be "appalling and indescribable confusion" if the Russians attacked. In the end, the Western European Union ordered him to hold the Rhine.

Forrestal had doubts about the plan. He thought it relied too much on the Soviets doing what was expected. He questioned if strategic bombing could win a war. Before spending millions on aircraft, he wanted some guarantees. A committee was formed to investigate. The report repeated that without enough regular forces, the air attack plan was all they had. It estimated that it would reduce Soviet industrial capacity by 30% to 40%. About 6.7 million people were expected to be hurt or killed, with 2.7 million deaths. Survivors would live without electricity or fuel. However, the committee doubted it would destroy civilian morale. Based on World War II experience, the opposite was more likely. A separate question was whether the plan could even be carried out successfully, given the poor information about the Soviet Union. Admiral Denfeld, for one, doubted it. He suggested a tactical air campaign to slow the Soviet advance into Western Europe instead. The Air Force pushed ahead with buying the long-range B-36 bomber. This led to a conflict between the Navy and the Air Force, known as the Revolt of the Admirals. Admiral Denfeld was replaced by Admiral Forrest Sherman.

What Happened Next?

Arguments between the military branches eased when the Korean War started. This led to a big increase in the defense budget. This allowed the Joint Chiefs of Staff to plan for a 20-division Army, a 143-wing Air Force, and a 402-ship Navy. The Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb in August 1949. This was much earlier than US intelligence had predicted. This led to new estimates of the Soviet nuclear supply. It was now expected they would have 10 to 20 bombs by mid-1950, and up to 200 by mid-1954. This was immediately added to the next version of the Offtackle war plan in October. Both sides were now expected to use nuclear weapons from the start of any fighting. The US now had to think about defending North America from air attacks. In March 1949, Truman signed a law to build 75 radar stations. But no money was given, so only some locations were chosen by January 1950.

New nuclear tests in April and May 1948 showed improved bomb designs. The new Mark 4 nuclear bomb, which came out in March 1949, was more practical than the older Fat Man bombs. Its new core used available nuclear material more efficiently. In May 1948, scientists started designing the Mark 5 nuclear bomb, a smaller and lighter weapon. The Soviet Union's atomic bombs pushed the US to develop even more powerful thermonuclear weapons. By December 1949, the Strategic Air Command had 521 bombers (B-29s, B-36s, and B-50s) that could deliver atomic bombs. It was estimated that SAC bombers would suffer 35% losses at night, and 50% if missions were flown during the day. Delivering the 292 atomic bombs called for by the Offtackle plan was considered possible. But there would be no ability to launch follow-up raids. A new jet bomber, the Boeing B-47 Stratojet, was being developed, but it would not be ready until 1953. The idea of using nuclear weapons to prevent war (nuclear deterrence) was not part of these war plans. Nuclear weapons were seen purely as tools for fighting a war.

In 1947, the United States European Command (EUCOM) ordered the only American division in Europe, the 1st Infantry Division, to gather together. It was relieved of its occupation duties in West Germany and told to restart its combat training. By 1950, it was still spread out. EUCOM looked for good places to bring it together. To build up US ground forces, the Joint Chiefs decided to send four more divisions to Europe in 1951. Plans for defending the Rhine were still considered weak. NATO was short 8,000 tanks, 9,200 half-tracks, and 3,200 artillery pieces. Equipment bought during World War II was becoming old or unusable. In September 1948, a general reported that the Army had 15,526 tanks, but only 1,762 were ready for use. By June 1950, 400 M26 Pershing tanks had been rebuilt as the new M46 Patton.

The war plans of the late 1940s were never actually used. It is not known if the Soviet Union would have taken over Western Europe, if the air attacks would have worked, or even who would have won such a war. The big difference between what the military had and what it was expected to do weighed heavily on the planners. They focused on what the Soviet Union *could* do, rather than what it *intended* to do. They believed the Soviet Union did not want to risk a war because its economy was so damaged. A calculated risk was taken based on that idea. In December 1947, Forrestal noted: "As long as we can outproduce the world, can control the sea and strike inland with the atomic bomb, we can assume certain risks otherwise unacceptable in an effort to restore world trade, to restore the balance of power-military power and to eliminate some of the conditions that breed war."

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |