Weapons and armour in Anglo-Saxon England facts for kids

From the 400s to the 1000s, people in Anglo-Saxon England used many different weapons. The most common weapon was the spear, which they used for throwing and stabbing. Other popular weapons included swords, axes, and knives. However, bows and arrows and slings were not used as often. For protection, warriors mostly used shields. Sometimes, they also wore mail (chainmail) and helmets.

Weapons were also important symbols for the Anglo-Saxons. They often showed a person's gender and social standing. In early Anglo-Saxon times, weapons were frequently buried with people in their graves. Most of these weapons were found in men's graves, but some were also found with women. Sometimes, weapons were buried in the ground or near rivers, not just in graves. Later, Christian writers in Anglo-Saxon England wrote texts that describe weapons and how they were used in battles. Famous poems like Beowulf and The Battle of Maldon mention these weapons.

Contents

How Do We Know About Anglo-Saxon Weapons?

We learn about Anglo-Saxon weapons and armor from three main sources: things found by archaeologists, old writings, and pictures. Each source tells us different things and has its own challenges.

What Archaeology Tells Us

Archaeologists have found many Anglo-Saxon weapons because people often buried them in graves during the early Anglo-Saxon period. This was a ritual, meaning it was a special custom. Weapons in graves could show a person's age, where they came from, or their importance in society. Later, some Anglo-Saxon weapons were found near rivers. Some historians think this might have been a return to an old custom of placing things in sacred water. It could also mean that battles were often fought near river crossings.

Finding weapons through archaeology helps us see how weapon styles changed over time and if different regions had different weapons. However, we have to remember that these buried weapons might not show all the types of weapons used every day.

What Old Writings Tell Us

Most of what we know about Anglo-Saxon warfare comes from writings made by Christian priests between the 700s and 1000s. These writers did not always describe weapons or how they were used in detail. For example, Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People talks about battles but gives few specifics. So, experts often look at writings from nearby groups like the Franks, Goths, or later Vikings to learn more.

Some poems, like Beowulf, Battle of Brunanburh, and The Battle of Maldon, also mention weapons in fights. But it's hard to know exactly when these poems were written. It's also unclear how much of the descriptions are true and how much is made up by the poets. Law codes and wills from the 900s and 1000s also give us some clues about the military gear used by important Anglo-Saxon people.

What Art Tells Us

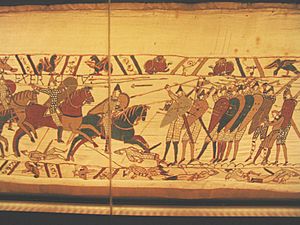

We can also see Anglo-Saxon soldiers with weapons in old sculptures and drawings in books. The famous Bayeux Tapestry also shows warriors and their weapons. But artists might have drawn things in a certain way because of art styles, not always showing exactly how weapons were used in real life.

Words for Weapons

In Old English, the language of Anglo-Saxon England, there were often many words for the same type of weapon. The Beowulf poem uses at least six different words for a spear. This suggests that these words had slightly different meanings. Some Anglo-Saxon groups might have even gotten their names from weapons. For example, the Angles might come from angul (meaning "barbed" or "hook"). The Franks might come from franca ("spear" or "axe"), and the Saxons from seax ("knife").

Old Anglo-Saxon laws say that only free men were allowed to carry weapons. The laws of King Ine (who ruled from 688 to 726 CE) said that if you helped someone else's servant escape by lending them a weapon, you would get a fine. The fine was higher for a spear than for a sword. Anglo-Saxons were very proud of their weapons and spent a lot of time making them look good and work well.

Types of Anglo-Saxon Weapons

Spears and Javelins

Spears were the most common weapons in Anglo-Saxon England. About 85% of early Anglo-Saxon graves with weapons contained spears. Around 40% of all adult male graves from this time had spears. In many Northern European societies, including Anglo-Saxon England, only free men could carry spears. Laws gave strict punishments to any enslaved person found with one.

In Old English, spears were usually called gār and spere. Some poems used more artistic names like æsc (meaning 'made of ash wood'), ord ('point'), and þrecwudu ('wood for harming'). A throwing-spear or javelin was often called a daroþ ('dart').

A spear had an iron spearhead on a wooden shaft, usually made of ash wood. Sometimes, the shaft was made of hazel, apple, oak, or maple. We don't know the exact length of most spears, but estimates from grave finds suggest they were between 1.6 and 2.8 meters (5 to 9 feet) long. The end of the spear shaft sometimes had an iron cap called a ferrule.

Spearheads were sometimes decorated with bronze and silver designs. A simple ring-and-dot pattern was common. The ferrule might also be decorated to match the spearhead. It's possible that the wooden shafts were painted too.

In battles, spears were used both for throwing and for stabbing in hand-to-hand combat. It's often hard to tell if a spear was made for throwing or thrusting. One exception is the angon, a barbed spear used for throwing. Once an angon pierced an enemy, its barbs made it very hard to pull out, which often caused serious injury. If it hit an enemy's shield, it would get stuck, making the shield heavy and difficult to use. These angons might have come from the Roman army's pilum javelins.

Experts think a thrown spear could travel about 12–15 meters (40–50 feet), depending on the thrower's skill and the spear's size. The poem The Battle of Maldon describes how javelins were used. In the story, a Viking threw a javelin at Earl Byrhtnoth, who was wounded even though he partly blocked it with his shield. Byrhtnoth then threw two javelins back, hitting a Viking in the neck and another in the chest. After more javelin throwing, both sides drew their swords and fought up close.

When used in hand-to-hand combat, a spear could be held under the arm or over the arm. Pictures show both ways. Sometimes, spears might have been held with both hands, but this meant the warrior couldn't use a shield for protection. To be more effective, groups of spearmen would stand close together to form a shield wall. They would protect each other with their shields and point their spears at the enemy. These formations were also called scyldburh ('shield-fortress').

Spears also had symbolic meanings. In one story by Bede, a Christian priest named Coifi threw a spear into his old pagan temple to show it was no longer sacred. In Anglo-Saxon England, the male side of a family was known as "the spear side."

Swords

The sword was a very important symbol in Anglo-Saxon times. It was often the most prized piece of military equipment. In Old English, swords were called sweord, but also heoru, bill, and mēce. Anglo-Saxon swords had straight, flat blades with two sharp edges. The part of the blade that went into the handle was called the tang. The handle, or hilt, had an upper and lower guard, a pommel (the knob at the end), and a grip. Pommels could be beautifully decorated, like the one from the Bedale Hoard with inlaid gold. These swords were usually 86–94 cm (34–37 inches) long and 4.5–5.5 cm wide. Some larger ones were up to 100 cm (40 inches) long and 6.5 cm wide.

Because old furnaces could only make small pieces of iron, sword blades were made by hammering these small pieces together. They would either flatten them into thin sheets and hammer them into a laminated blade, or weld thin rods together. Some blades were made using a special method called pattern welding. In this method, iron strips were twisted together and then welded. This twisting removed impurities and created cool patterns in the finished blade, often a herringbone pattern. Anglo-Saxon writings mention these patterns with terms like brogenmæl ('weaving marks'). This shows that these patterns were important and desired. Many blades also had a fuller, a shallow groove along the blade. The fuller made the blade lighter without making it weaker.

A few swords had runic writing on them. A sword from the 500s found in Gilton, Kent, said, "Sigimer Made This Sword." Old texts also show that swords sometimes had names, like the Hrunting sword in Beowulf. From the 500s onwards, some swords had rings attached to the upper guard or pommel. These rings were often decorated. Sometimes, a soldier could tie a cord to the ring and hang the sword from their wrist. Other times, the rings were just for decoration or had a special meaning.

The sword's case, or scabbard, was called a scēaþ in Old English. Scabbards were usually made of wood or leather and often lined with fleece or fur. The inside might have been greased to stop the sword from rusting. Some scabbards had metal parts at the top and bottom for extra protection. A small strap sometimes attached a bead of glass, amber, or crystal to the scabbard's neck. These beads might have been used as good luck charms. Later Viking stories mention swords with "healing stones," which might be similar to these Anglo-Saxon beads.

Swords were carried either from a baldric (a strap over the shoulder) or from a belt around the waist. The shoulder strap was popular early on, but carrying swords on a belt became more common later. The Bayeux Tapestry only shows swords carried on belts.

The weight of these swords and descriptions in poems like The Battle of Maldon suggest they were mostly used for cutting and slashing, not for thrusting. Some Anglo-Saxon skeletons show sword cuts, especially to the left side of the skull.

Knives

In Old English, a knife was called a seax. This word covered single-edged knives from 8 to 31 cm (3 to 12 inches) long. It also referred to "long-seaxes" (or single-edged swords) that were 54 to 76 cm (21 to 30 inches) long. Early seaxes were common in Frankish graves in the 400s and became popular in England later.

Knives were mostly used for daily tasks, like preparing food. But they could also be used in fights. Some warriors used a mid-to-large scramsax instead of a sword. This special knife had a unique length and a single cutting edge. It was 10 to 50 cm (4 to 20 inches) long and usually had a long wooden handle.

Experts have identified six main types of Anglo-Saxon knives based on their blade shapes. Anglo-Saxon seaxes were often made using pattern-welding, even when this method was less common for swords. Blades were sometimes decorated with lines or metal designs. Some even had the owner's or maker's name on them. The seax was kept in a leather sheath, which might be decorated with patterns and silver or bronze parts. Graves show that the sheath was worn on a belt, with the handle on the right side.

Most Anglo-Saxon men and women carried knives for cooking and other chores. In a fight, a knife could be used to finish off an injured enemy or in a close brawl. Longer seaxes were probably used as weapons, while shorter ones were general tools. Some think long-seaxes were for hunting, while others believe they were more of a status symbol for free men.

Axes

In Old English, axes were called æces, which is where our modern word "axe" comes from. Most axes found in early Anglo-Saxon graves were small with straight or slightly curved blades. These hand-axes were mainly tools, but they could be used as weapons if needed. We rarely find the full wooden handles, so it's hard to know the exact size of these axes.

Several examples of the francisca, or throwing axe, have been found in England. These axes have curved heads that set them apart from regular hand axes. There were two main types of throwing axes: one with a curved edge and another with an 'S'-shaped edge. Roman writers in the 500s described the Franks throwing these axes at enemies before fighting hand-to-hand. The name francisca comes from the Franks. However, the throwing axe seems to have stopped being used by the 600s, perhaps because battle formations became more organized. But it came back into use in the 700s and 800s when the Vikings adopted it.

Bows and Arrows

Anglo-Saxon archery equipment is rare to find. Iron arrowheads have been found in only about 1% of early Anglo-Saxon graves. Sometimes, tiny bits of wood from bow staves are found in the soil. In one rare case, at Chessel Down cemetery, arrows and a bow were buried with someone. It's possible that other arrows were hardened by fire or had tips made of bone or antler, which would not survive well in graves. Since bows and arrows were made of wood, they probably didn't last long in the ground, so they might have been buried more often than we think. In Old English, a bow was called a boga.

In nearby parts of Europe with different soil, more archery equipment has been found. For example, about forty bow staves and many arrows were found in Denmark, dating to the 200s or 300s CE. This suggests that long bows were common in Northwestern Europe during the early medieval period. Longbows were made from a single piece of wood, and the string was made of hair or animal gut. An Anglo-Saxon bow could probably shoot an arrow about 150 to 200 meters (500 to 650 feet). However, the arrow's power would drop a lot after 100 to 120 meters (325 to 400 feet), causing only minor wounds.

Anglo-Saxon arrowheads are grouped into three main types. The first type is leaf-shaped, usually with a socket to attach to the wooden shaft. The second type is bodkins, which are long and pointed. The third type is barbed arrowheads, which usually had a tang that was pushed into the shaft or tied to it. Leaf-shaped and barbed arrowheads probably came from hunting arrows. Bodkins were likely designed to go through armor, like chainmail or helmets, if shot from close range.

It's sometimes hard to tell the difference between large arrowheads and small javelin heads because their sizes overlap (5.5 cm to 15.5 cm, or 2 to 6 inches).

Even though bows are rarely found in graves, they appear more often in Anglo-Saxon art and writings. The Franks Casket from the 700s shows an archer defending a hall. The Bayeux Tapestry from the 1000s shows twenty-nine archers, but only one is Anglo-Saxon; the rest are Norman. Experts think Anglo-Saxons mainly used bows for hunting, and most men probably knew how to use them for this purpose.

Slings

There is little evidence that slings were used as weapons in war. They were usually shown as tools for hunting. In Old English, a sling was called a liðere or liðera. An old story about Saint Wilfrid from the 700s tells of him and his friends being attacked by pagans. One of Wilfrid's friends threw a stone from a sling, killing the pagan priest. However, the Bayeux Tapestry shows a man hunting birds with a sling. Some experts believe slings were not considered war weapons, except as a last resort. The story about Saint Wilfrid might have been written to remind people of Bible stories.

Armor and Defensive Gear

Shields

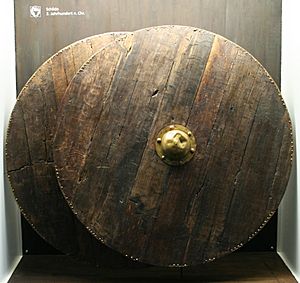

The shield was a very common piece of war equipment for the Anglo-Saxons. Nearly 25% of male Anglo-Saxon graves contain shields. In Old English, a shield was called a bord, rand, scyld, or lind (meaning "linden-wood"). Anglo-Saxon shields were round pieces of wood made from planks glued together. In the center, an iron boss was attached. Shields were often covered in leather to hold the planks together and decorated with bronze or iron parts. Some old writings and pictures show shields that were curved, but archaeologists haven't found physical proof of this yet. No painted Anglo-Saxon shields have been found, but painted shields from the same time in Denmark suggest that some Anglo-Saxon shields might have been painted. The Beowulf poem describes shields as "bright" and "yellow."

Old English poems always say shields were made of lime (linden-wood), but archaeologists have found few actual examples. Evidence shows that alder, willow, and poplar wood were most common. Shields made of maple, birch, ash, and oak have also been found. Shields varied greatly in size, from 0.3 to 0.92 meters (1 to 3 feet) across. Most were between 0.46 to 0.66 meters (1.5 to 2.2 feet) in diameter. Their thickness ranged from 5 mm to 13 mm, but most were 6 mm to 8 mm thick.

Anglo-Saxon shield bosses are divided into two main types based on how they were made. The carinated boss was the most common type. This design came from mainland Europe and was found in England from the 400s to the mid-600s. The other type was the tall cone boss, common from the 600s onwards. These bosses were made of iron sheets welded together. Iron or bronze rivets were used to attach the boss to the shield, usually four or five, but sometimes up to twelve.

Behind the boss, the shield had a cut-out opening with an iron grip attached, so the shield could be held. Grips were usually 10 to 16 cm (4 to 6 inches) long.

Most Anglo-Saxon warriors only had shields for protection. The shield was probably the most important defensive item. The shield-wall formation, where warriors stood together with their shields, was a strong symbol of the two sides facing each other in battle. Smaller shields were lighter and easier to move, good for small fights and hand-to-hand combat. Larger shields were better for big battles, offering more protection from thrown weapons and needed for forming a shield wall.

Mail Armor

In Old English, mail armor (chainmail) was called byrne or hlenca. It is often mentioned in later Anglo-Saxon writings, but few actual pieces have been found by archaeologists. The only complete Anglo-Saxon mailcoat found was at Sutton Hoo, but it is badly damaged by rust. So, the lack of archaeological finds might just be because mail rusts easily. A complete mailcoat from the 300s or 400s, similar to what Anglo-Saxons probably used, was found in Denmark.

The mailcoat from Sutton Hoo had iron rings 8 mm (0.3 inches) in diameter. Some rings were closed with copper rivets, meaning the coat was made of rows of riveted rings alternating with forged (solid) rings. When worn, the coat probably reached the hip. Making a mailcoat involved first making thin metal wire. The wire was then coiled tightly around a ring. The smith would cut off individual rings, heat them, and soften them. Finally, the rings were joined and closed by welding and riveting. After being made, the coat was hardened by being packed in charcoal and reheated.

Mail armor greatly protected a warrior by spreading out the force of enemy blows. Warriors wearing mail had a big advantage. It was especially good against sword or axe cuts because the impact was absorbed by many rings. However, mail was less effective against spears. The concentrated force of a spear could break a few links and let the spear enter the body. Mailcoats were also very heavy and made it harder for warriors to move quickly. Mail also rusted easily and needed constant care.

Helmets

The Old English word for helmet was helm. In battle, helmets protected the wearer's head. Evidence shows that helmets were never very common in Anglo-Saxon England, though their use might have increased by the 1000s. Cnut the Great ordered in 1008 that warriors on active duty must have a helmet. The Bayeux Tapestry also suggests that helmets were standard military gear for the Anglo-Saxon army by 1066. Later Anglo-Saxon writings, like Beowulf, also mention helmets.

Four mostly complete Anglo-Saxon helmets have been found. Archaeologists have also found other helmet fragments. All the found helmets are quite different in how they were made and decorated. It's possible that most helmets were made of hardened leather and simply did not survive over time.

The earliest known helmet was found at Sutton Hoo, from an important burial in the 600s. This helmet's main part was made from one piece of metal. It had cheek pieces, a metal neck guard, and a face mask. The helmet was richly decorated with a winged dragon on the face plate and a two-headed dragon along the top. Embossed foil sheets with five different designs covered almost the entire helmet. The decorations are similar to those found in England, Germany, and Scandinavia. The helmet itself is like ones found in Sweden, suggesting it might have been made there or by a Swedish craftsman in England. Fragments of similar helmet crests found elsewhere suggest these helmets might have been more common than we think.

Some helmets had boar figures on top, like the mid-600s Benty Grange helmet. This helmet, found in 1848, had an iron frame and a bronze boar figure on its crest. The boar had garnet eyes set in gold and gilded tusks and ears. Another bronze boar, possibly a helmet crest, was found in a female grave in Guilden Morden, but no other helmet parts were there. The Pioneer Helmet also had an iron boar crest.

The Coppergate Helmet, from the mid-to-late 700s, was found in a Viking settlement in York, but it was made by the Angles. It was made of iron plates. Iron cheek-pieces were hinged to the sides, and a mail curtain protected the neck at the back. The nasal plate, which covered the nose, had animal engravings and ended in small dog-like designs. On the helmet's two crests, there were Latin writings praising the Christian Trinity.

How Weapons Were Made

Basic weapons like spearheads and knives could be made by any smith. However, swords and many other complex weapons likely needed a specialist. Archaeologists have found some Anglo-Saxon smith's tools. A set from the 600s, including an anvil, hammers, tongs, a file, shears, and punches, was found in a grave at Tattershall Thorpe.

The artistic styles on Anglo-Saxon weapons are very similar to weapon art found in other parts of northern Europe and Scandinavia. This shows that these regions were always in contact. The English adopted some ideas from outside, but English developments also influenced other cultures. For example, the ring-sword was likely created in Kent in the mid-500s. By the 600s, it was used across Europe by Germanic-speaking peoples and even in Finland.

|

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |